|

Introduction: The US Food and Drug Association (FDA) released its requirements for the non-proprietary naming of biological products in January 2017. Before the FDA’s release, the Alliance for Safe Biologic Medicines (ASBM) asked physicians for their views on the labelling and naming of biosimilar medicines. |

Submitted: 9 January 2017; Revised: 12 February 2017; Accepted: 13 February 2017; Published online first: 27 February 2017

Biological medicines are therapeutic proteins produced using living cells. A copy of an original biological made by a different manufacturer is referred to as a biosimilar or follow-on biological rather than a generic drug because it will be similar, not identical, to the product it copies. Biosimilars are also referred to as subsequent entry biologics (SEBs) in Canada. As a result of the abbreviated biosimilar approval pathway [1], biosimilar medicines are now available in the US market.

The market uptake of biosimilars in the US will depend on regulatory policies [2], for which an agreed naming and labelling system will be key. A survey of the views of European physicians on familiarity of biosimilar medicines has demonstrated the need for distinguishable non-proprietary names to be given to all biologicals [3]. There have been calls for clear regulation in this area from Latin America [4], Malaysia [5] and beyond.

Since FDA has only distributed draft guidance on the naming of biosimilar medicines [6] at time of the survey, feedback from the physicians who prescribe biologicals may well be helpful in determining how these drugs are to be regulated. The Alliance for Safe Biologic Medicines (ASBM) invited 5,423 physicians in the US to complete a study on the naming of biologicals. A total of 433 physicians responded, of which 400 prescribers of biologicals qualified and completed the study. Prescribers were asked for their feedback on the non-proprietary biologicals naming proposal issued by FDA in August 2015 [6].

FDA has proposed a new policy that would require every biological – whether originator or biosimilar – to have a distinct non-proprietary scientific name. Prescribers concluded that FDA was right to require a distinct non-proprietary scientific name for every biological product – originator or biosimilar – that FDA had approved.

Product labelling is seen at the heart of building user confidence in biosimilars [7]. In a subsequent study, the ASBM invited 9,813 prescribers to complete a study on the labelling of biologicals. 624 of these responded, of which 400 qualified and completed the study. Physicians who completed the study were asked what information they would like to see in a biological product label in order to choose between multiple biosimilars and their reference products. Physicians were asked what information could be included in a label, such as what clinical data should be present; whether or not the product was a biosimilar; and whether or not it was interchangeable.

All the information included in the labelling survey was considered important by the physicians surveyed. The greatest importance was accorded to an indication that the drug was a biosimilar. Physicians responded that including information on interchangeability was slightly less important than this.

Physician biosimilars labelling survey

Four hundred physicians were recruited in the US to complete a 15-minute web-based questionnaire on biosimilar labelling. In a separate, independent study, 400 prescribers were recruited in the US to complete a 15-minute web-based questionnaire on biosimilar naming. Participants in both surveys received a standard cash stipend of US$25 for their time to complete the survey.

All participants in the labelling survey were located in the US. They were recruited from a large, reputable panel of physicians and were all board certified in one of the following six specialities: dermatology, endocrinology, nephrology, neurology, oncology, or rheumatology. All participants prescribed biological medicine.

Of the 400 physicians who completed the labelling survey, 23% specialized in dermatology, 15% in endocrinology, 16% in nephrology, 15% in neurology, 16% in oncology, and 16% in rheumatology.

Prescribers completing the labelling survey worked in different settings. Twenty-six per cent of respondents worked in a community setting, 24% worked in an academic medical centre, 22% worked in a multi-speciality clinic, 17% worked in a private or family practice, 8% worked in a hospital, see Figure 1.

A total of 7% of participants in the labelling survey had spent 1–5 years in practice, 26% had spent 6–10 years, 41% had spent 11–20 years, 22% had spent 21–30 years, and 4% had spent more than 30 years in practice.

Physician biosimilars naming survey

The 400 participants in the naming survey were also based in the US. They were recruited from a large, global panel of healthcare professionals. Participants specialized in one of the following seven therapeutic specialities: dermatology, endocrinology, gastrointestinal, nephrology, neurology, oncology or rheumatology.

Among physicians completing the naming survey, 13% specialized in dermatology, 15% in endocrinology, 14% in gastrointestinal, 14% in nephrology, 14% in neurology, 16% in oncology, and 14% in rheumatology.

Prescribers completing the naming survey worked in different settings. 26% of respondents worked in an academic medical centre, 25% in a community setting, 20% in a private or family practice, 18% in a multi-specialist clinic, 7% in a hospital, and 2% in a military/veterans affairs hospital, see Figure 2.

A total of 7% of the physicians completing the naming survey had spent 1–5 years in practice, 33% had spent 6–10 years in practice, 32% had spent 11–20 years, 21% had spent 21–30 years, and 6% had spent more than 30 years in practice.

Participants in the naming survey were asked about their familiarity with FDA’s ‘Orange Book’ [8], the resource for Approved Drug Products with Therapeutic Equivalence Evaluations. The ‘Orange Book’ is a reference that identifies drug products approved on the basis of safety and effectiveness by FDA. Only 13% considered themselves very familiar with the book, 33% somewhat familiar, 26% vaguely familiar, and over a quarter (28%) had never heard of it. Only 4% used the Orange Book on a daily basis, 17% used it weekly, 14% used it monthly, 28% used it rarely, and 37% never used it.

Asked about their familiarity with FDA’s ‘Purple Book’ [9], that is, the resources for Lists of Licensed Biological Products with Reference Product Exclusivity and Biosimilarity or Interchangeability Evaluations, 8% were very familiar, 23% were somewhat familiar, 28% were vaguely familiar, and 41% had never heard of it. Only 4% used the Purple Book daily, 11% used it weekly, 12% used it monthly, 23% used it rarely, and over half (51%) never used it. Information contained in the Purple Book is designed to help enable a user to see whether a particular biological product has been determined by FDA to be biosimilar to or interchangeable with a reference biological product.

All physicians questioned in the naming survey claimed that they identified all medicines that they prescribed (biological and chemical) in the medical record.

Asked how they identified a medicine in the patient record, 25% said by scientific name, 34% by brand name, and 39% said it varied by medicine. Asked whether they would report an adverse event by using a drug’s product name or National Drug Code (NDC) number, 47% said they would use the brand name, 38% said they would use the scientific name, 2% would use the NDC number, and 13% had no preference.

Participants in the naming survey were asked for their attitudes and beliefs on product naming for originator and biosimilar products. 72% of respondents thought that if medicines had the same non-proprietary scientific name then they were probably structurally identical, 16% thought they would not be structurally identical, and 12% had no opinion. If two products have the same non-proprietary scientific name then 68% of respondents thought that a patient could safely receive either product and expect the same result. Twenty-one per cent of respondents would not expect the same result, and 11% had no opinion.

Asked about switching (when a patient is switched from one medicine to another), 60% of respondents thought that patients could safely be switched between two medicines that had the same non-proprietary scientific name and expect the same results. A quarter of respondents (25%) thought that patients could not safely be switched between two medicines with the same non-proprietary scientific name, 14% of respondents had no opinion.

Physician responses to biosimilar labelling survey

On a scale of 1–5, where 1 is not important at all and 5 is very important, 90% of the physicians questioned rated the importance of whether a product label for a biosimilar should clearly indicate that it is a biosimilar as either a 4 or 5, see Figure 3. On the question of post-marketing data, 79% of respondents rated the importance of including this data on the biosimilar label as either a 4 or 5, see Figure 4. On the question of interchangeability, 79% of respondents rated the importance of including whether or not a biosimilar is interchangeable as either a 4 or 5, see Figure 5. The responses of physicians to questions on biosimilar labelling are shown in Table 1.

Physician responses to biosimilar naming survey

In the naming survey, prescribers were asked whether FDA should require a distinct non-proprietary scientific name for every biological product FDA had approved – whether originator or biosimilar. FDA has recently proposed a distinct non-proprietary scientific name for all products, whether originator or biosimilar. This is intended to aid the process of pharmacovigilance and accurate prescribing and dispensing of medicines.

Respondents were asked for their views on the information that should be included in a product name and for their attitudes and beliefs on substitution.

Responses to questions in the physicians’ naming survey are shown in Table 2.

The spread of prescribers’ responses to questions related to the information contained in the representative suffix are given in Figure 6.

Generally speaking, all issues raised in the labelling survey were considered by the physicians surveyed to be very important for label inclusion. The inclusion of an indication of interchangeability was considered very important by 54% of the physicians. In fact, the physicians concluded that interchangeability was – of all the features included in the survey questions – the least important feature, with an average score of 4.1 out of 5. On average, the physicians gave the highest score, 4.4, to indicating that the drug was a biosimilar.

Segment differences were examined for all issues included in the survey. Segments among physicians included specialty, time spent working in health care, and practice setting. Very few specialty differences were noted and no differences for practice setting were noted. In general, the longer a physician had been in practice, the more important they thought it was to include the features mentioned in the survey on the biosimilar product label.

FDA proposal for a random suffix on a product’s name that does not indicate the manufacturer was not broadly welcomed, with only 9% of respondents agreeing with FDA. Instead, most physicians (60%) would prefer a suffix on the non-proprietary scientific name that is indicative of the product’s manufacturer. A third of respondents (32%) had no opinion.

In the naming survey, it was clear that respondents were not in complete agreement on how biological medicines, whether originators or biosimilars, are named. Reaching an agreement on the naming of these medicines will be key in building user confidence in biosimilars. The data presented here provide important feedback from a wide range of physicians who prescribe biologicals in the US. The findings will be helpful in determining how these biosimilar medicines are regulated in future.

|

Key points of the 2015 physicians naming and labelling survey

|

The Alliance for Safe Biologic Medicines (ASBM) is an organization composed of diverse healthcare groups and individuals – from patients to physicians, innovative medical biotechnology companies and others – who are working together to ensure patient safety is at the forefront of the biosimilars policy discussion. The activities of ASBM are funded by its member partners who contribute to ASBM’s activities. Visit www.SafeBiologics.org for more information.

Competing interests: Harry L Gewanter, MD, FAAP, FACR, Chairman of the Alliance for Safe Biologic Medicines (ASBM), and Mr Michael S Reilly, Esq, Executive Director; are employed by ASBM.

This paper is funded by ASBM.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Harry L Gewanter, MD, FAAP, FACR, Chairman

Michael S Reilly, Esq, Executive Director

Alliance for Safe Biologic Medicines, PO Box 3691, Arlington, VA 22203, USA

References

1. Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act of 2009, Public Law 111-148, Sec. 7001–7003, 124 Stat. 119. Mar. 23, 2010.

2. Cohen JP, Felix AE, Riggs K, Gupta A. Barriers to market uptake of biosimilars in the US. Generics and Biosimilars Initiative Journal (GaBI Journal). 2014;3(3):108-15. doi:10.5639/gabij.2014.0303.028

3. O Dolinar R, Reilly MS. Biosimilars naming, label transparency and authority of choice – survey findings among European physicians. Generics and Biosimilars Initiative Journal (GaBI Journal). 2014;3(2):58-62. doi:10.5639/gabij.2014.0302.018

4. Feijó Azevedo V, Mysler E, Aceituno Álvarez A, Hughes J, Javier Flores-Murrieta F, Ruiz de Castilla EM. Recommendations for the regulation of biosimilars and their implementation in Latin America. Generics and Biosimilars Initiative Journal (GaBI Journal). 2014;3(3):143-8. doi:10.5639/gabij.2014.0303.032

5. Abas A, Siew Khoon Khoo Y. Regulation of biologicals in Malaysia. Generics and Biosimilars Initiative Journal (GaBI Journal). 2014;3(4):193-8. doi:10.5639/gabij.2014.0304.044

6. GaBI Online – Generics and Biosimilars Initiative. FDA issues draft guidance on biosimilars labelling [www.gabionline.net]. Mol, Belgium: Pro Pharma Communications International; [cited 2017 Feb 12]. Available from: www.gabionline.net/Guidelines/FDA-issues-draft-guidance-on-biosimilars-labelling

7. European Biopharmaceutical Enterprises. Tell me the whole story: the role of product labelling in building user confidence in biosimilars in Europe. Generics and Biosimilars Initiative Journal (GaBI Journal). 2014;3(4):188-92. doi:10.5639/gabij.2014.0304.043

8. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Orange Book: approved drug products with therapeutic equivalence evaluations [homepage on the Internet]. [cited 2017 Feb 12]. Available from: http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/ob/default.cfm

9. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Purple Book: lists of licensed biological products with reference product exclusivity and biosimilarity or interchangeability evaluations [homepage on the Internet]. [cited 2017 Feb 12]. Available from: http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DevelopmentApprovalProcess/HowDrugsareDevelopedandApproved/ApprovalApplications/TherapeuticBiologicApplications/Biosimilars/ucm411418.htm

|

Author for correspondence: Michael S Reilly, Esq, Executive Director, Alliance for Safe Biologic Medicines, PO Box 3691, Arlington, VA 22203, USA |

Disclosure of Conflict of Interest Statement is available upon request.

Copyright © 2017 Pro Pharma Communications International

Permission granted to reproduce for personal and non-commercial use only. All other reproduction, copy or reprinting of all or part of any ‘Content’ found on this website is strictly prohibited without the prior consent of the publisher. Contact the publisher to obtain permission before redistributing.

Source URL: https://gabi-journal.net/naming-and-labelling-of-biologicals-a-survey-of-us-physicians-perspectives.html

Author byline as per print journal: Michael S Reilly, Esq; Harry L Gewanter, MD, FAAP, FACR

|

Introduction: World Health Organization (WHO) recommendations for the regulation of biosimilars form the basis of guidelines used across most of Latin America. However, the pace at which the region moves toward reaching its potential of having safe and effective biosimilars has been slow. The Alliance for Safe Biologic Medicines used a questionnaire to survey a sample of Latin American prescribers in order to determine what they understood about biosimilars, how they use them, and their concerns for the future. |

Submitted: 3 October 2015; Revised: 23 November 2015; Accepted: 1 December 2015; Published online first: 14 December 2015

A total of 399 prescribers from four countries in Latin America: Argentina (n = 99, 25%); Brazil (n = 101, 25%); Colombia (n = 100, 25%); and Mexico (n = 99, 25%) completed a 15- minute webbased questionnaire written in their native language (Spanish for prescribers in Argentina, Colombia and Mexico; Portuguese for prescribers in Brazil), for which they were paid a stipend of US$75. The questionnaire was sent to 6,650 members of a global market research panel. The source used to identify the prescribers for this study was the M3 Global Research, a physician research panel. The only criteria necessary for inclusion in the study were that prescribers had to be in one of the target therapeutic specialties, in one of the target countries, and have requisite experience prescribing biological medicines. The overall study response rate was 6% (399 respondents of 6,650 asked who qualified for, and completed, the survey). Open-ended responses were translated into English for analysis and reporting purposes.

The primary therapeutic areas for participating prescribers (respondents) across all countries were as follows: Dermatology (22%); Oncology (18%); Neurology (18%); Endocrinology (17%); Rheumatology (13%); Nephrology (7%); Haematology oncology (2%); Transplant (1%); Metabolism (1%); and Other, including endocrinology metabolism and psychiatry, (2%).

Respondents across all countries were based in a range of practices: Hospital (32%); University Teaching Hospital (21%); Private multi-specialty clinic (18%); Traditional, non- government, medical practice (13%); Private primary care clinic (11%); Government-run multi-specialty clinic (2%); Government-run primary care clinic (1%); and Other (3%).

Taking all the countries together, most respondents had been working in medical practice for between 11–20 years (mean = 14.3 years). This varied according to country, see Table 1. Nearly two thirds (59%) of prescribers in all countries conducted more than 50 appointments per week, 36% conducted between 20–50 appointments and 5% conducted fewer than 20 appointments per week.

A total of 88% of respondents from all the countries involved in the study said that they prescribed biological medicines, see Table 2. Despite this, more than a third (35%) overall said they did not consider themselves familiar with biosimilars, see Figure 1. Of the countries surveyed, Argentinian prescribers were the least familiar with biosimilars, with 40% of respondents reported having either never heard of biosimilars or being unable to define them. Brazilian prescribers were the most familiar, with 28% never having heard of or being unable to define biosimilars.

Latin American prescribers reported having learned about biosimilar medicines in a number of ways. A total of 260 prescribers were given five categories by which they might have learned, and asked to select all that applied. Overall: 71% claimed to have gained familiarity by attending seminars and conferences; 55% through self-study; 32% through education that had been sponsored by biosimilar companies; 18% through clinical trial participation; and the remaining 4% by other means.

How respondents reported having learned about biosimilar medicines varied by country. For instance, nearly a third of prescribers in Argentina (29%) claimed to have learned about biosimilars through clinical trial participation, whereas just over a tenth of prescribers in Brazil (12%) reported learning though clinical trial participation. A relatively high number of prescribers in Brazil (60%) reported learning by self-study, compared with only 39% in Argentina. Over half the prescribers in Argentina (53%) claimed they became familiar with biosimilars with the help of (potentially biased) information from the companies that make biosimilars.

All 399 respondents were asked about their levels of familiarity with biosimilars. 35% (139) reported either never having heard of biosimilars or having heard of them ‘but could not define them.’

This subset (subgroup) of 139 respondents answered questions about how they would prefer to learn about biosimilars. Of these, only 37% of prescribers across the region said that they wanted to learn through pharmaceutical companies. In Argentina, this percentage was slightly higher (43%), although this is lower than the percentage of prescribers in Argentina who reported actually having learned about biosimilars from pharmaceutical companies (53%).

The majority of respondents in all countries said they would prefer to learn about biosimilars during national medical conferences and symposia (80% in Argentina; 89% in Brazil; 69% in Colombia; 71% in Mexico). A similar proportion of respondents said they would prefer to learn about biosimilars during inter national medical conferences and symposia (71% overall).

The 399 respondents were asked how familiar they were with ‘non-comparable biologicals’ (‘bio-copies’). The term noncomparable biological refers to a copy of an approved biological drug but differs from the definition of a biosimilar in that it lacks a complete biocomparability study and/or clinical trials. Non-comparable biologicals are copies that do not present simi lar safety and efficacy to the innovative product [1]. Across the whole region, only 6% said they had a complete understanding, with 35% saying they had a basic understanding. Nearly half the respondents (47%) had heard of non-comparable biologicals but could not explain them, and 12% had never heard of them.

Only half (49%) of the 399 prescribers were aware of the difference between biologicals, biosimilars and non-comparable biologicals. This figure was only 41% in Argentina.

Over 50 years ago the World Health Organization (WHO) established an International Nonproprietary Name (INN) Expert Group/WHO Expert Committee on Specifications for Pharmaceutical Preparations in order to assign non-proprietary names to medicinal substances. This system has been in place ever since, and it currently covers naming of biological medicines.

Biological medicinal products are an increasingly important sector of therapeutic and prophylactic medicines. Biological active substances now comprise more than 40% [2] of applications to the INN Programme and the percentage is increasing. Because of their complexity, bioequivalence cannot be easily established for a product containing a biological substance.

WHO has therefore proposed a scheme, applicable prospectively and retrospectively to all biological substances assigned INNs, that could be adopted on a voluntary basis by any regulatory authority and would be recognized globally. This voluntary scheme is intended to provide a unique identification code (Biological Qualifier, BQ), distinct from the INN, for all biological substances that are assigned INNs.

The BQ is proposed to complement the INN for a biological substance and uniquely identify directly or indirectly the manufacturer of the active substance in a biological product.

Nearly a third (30%) of responding prescribers across all the countries surveyed reported that they were not aware that a biosimilar may be approved for all the indications of the innovator product on the basis of clinical trials in only one of a limited number of those indications. This percentage varied by country, with 33% of prescribers in Colombia and just over a third of respondents in Argentina (37%) claiming to be unaware. A total of 28% of respondents in Mexico and 23% in Brazil reported being unaware of this aspect of biosimilar approval.

Just over half of the respondents overall (54%) said that they assumed that all biosimilars go through the same regulatory process for approval as the original biological products.

74% reported assuming that two products sharing the same non-proprietary name, for example, infl iximab and trastuzumab, would be approved for all the same indications. Just over a quarter (26%) of respondents in all countries surveyed said that they did not make this assumption.

There was confusion among the respondents over whether an identical nonproprietary name suggests or implies an identical structure. Over half (54%) of the respondents in these countries said they believe that products that share the same non-proprietary name are structurally identical.

Most prescribers (75%) reported being aware that WHO has proposed adding a four-letter suffix, the BQ, to the nonproprietary or scientific name of a biological, in order to clearly distinguish similar biologicals from one another [3]. This figure was greatest in Argentina (82%) and lowest, although still the majority, in Colombia (67%).

Nearly all responding prescribers in the countries surveyed (94%) thought that the distinguishable naming proposal would be useful to help them ensure that their patients receive the medicine that had been prescribed for them. Only 3% of respondents from Brazil, and 3% from Mexico, thought that a BQ would not be useful, while a surprising 11% of prescribers in Colombia thought it would not be useful.

How medicines are identified by the respondents was found to vary between countries. Overall, nearly two thirds (57%) reported identifying drugs in patient records exclusively by their non- proprietary/generic name. According to the study results, respondents in Brazil were the least likely to do this, see Figure 2.

How biologicals were identified when reporting adverse events (AEs) varied widely. Across all countries, 28% of the respondents claimed they would identify a product by its non-proprietary/generic name when reporting an AE. A total of 41% claimed they would identify a product by its product or brand name, and 32% said they identified products by non-proprietary or product name equally when reporting AEs.

Considerably less than half (38%) of respondents across the countries surveyed report every AE. As many as 9% of the respondents reported that they never reported AEs while 25% claimed they rarely reported AEs, and 28% said they reported only some AEs. This is despite the fact that, in the words of the survey question: ‘It is acknowledged that physicians play an important role in the identification and reporting of unexpected or serious adverse events to their national regulatory agencies and manufacturers’ [4].

Several reasons were offered by these physicians in order to explain their failure to report AEs. Across all countries included in the study, nearly half (48%) responded that they were not sure about the reporting process, e.g. who to send the report to, how to submit the report. An additional 15% said they did not have enough time to report AEs, 10% said they did not receive any feedback as to whether other events had been reported for the product, and 7% said they were not sure about the information required to submit an AE report. This last reason was given by between 2% and 7% of respondents, but by a surprising 17% of responding prescribers from Brazil. Finally, 4% said they did not know the outcomes of events that are reported, 3% said that they did not believe the reports would be useful, and 3% were concerned about professional liability if an AE was reported.

Only about half of responding prescribers (51%) said that they consistently used the batch number when reporting AEs, with 16% saying that they sometimes used it. It is widely recommended that all appropriate measures should be taken to identify clearly any biological medicinal product which is the subject of a suspected adverse reaction report, noting both its brand name and batch number [4]. A worrying 18% of respondents said they never used the batch number, with a further 16% saying they only rarely used it.

As before, the reasons given for not including batch numbers in AE reports varied between countries. Forgetting to include the number was cited by an alarming 42% of responding prescribers from Brazil and 35% from Argentina (but only 6% in Colombia and 8% in Mexico). Surprisingly, 16% of responding prescribers from Brazil and 17% from Mexico said they were not sure what the batch number was for. Perhaps one of the reasons that so few prescribers in Colombia reported neglecting to include the batch number was that three quarters (75%) of these respondents said they did not have it available at the time of reporting. In addition to these explanations, a small number (between 0% and 6%) said they were not sure where to find the batch number. A sizeable 42% of respondents from Mexico, and 23% of respondents from Argentina, gave other reasons not listed above.

Half (50%) of responding prescribers across the countries surveyed said they believed that if two biological medicines had the same non-proprietary scientific name, a patient could receive either product and expect the same result. This percentage varied between countries. In Colombia, only just over a third (34%) of responding prescribers said they believed this.

Slightly fewer (44% of respondents) said they believed that two biologicals sharing the same non- proprietary name implied that patients could safely be switched between them during a course of treatment, and the same results expected. Again, this percentage differed between countries, with less than a third (27%) from Colombia thinking that patients could be safely switched between the two medicines during a course of treatment.

Most responding prescribers (64%) said that they would not be comfortable switching between biologicals for cost reasons rather than medical reasons. This was true for respondents from all countries, but most marked in Colombia where 88% of respondents said they would not switch during treatment.

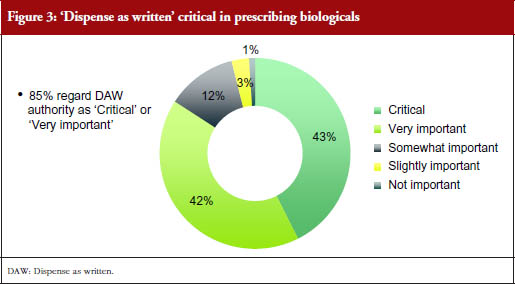

The authority of prescriber versus pharmacist when selecting biologicals showed some variation between the countries surveyed. In all countries, over 80% of responding prescribers thought that sole authority was either critical or very important. Overall, the prescriber’s sole authority over deciding, with their patients, the most suitable biological medicine, was considered critically important by over half (55%) of responding prescribers. However, in Brazil only 35% thought sole authority was critical, with 53% reported thinking it was very important.

The questionnaire asked: ‘In a situation where substitution by a pharmacist were an option in your country, how important would it be to have the authority to prevent pharmacist substitution and ensure the patient receives the prescription you intended to prescribe?’

This ‘dispense as written’ (DAW) authority was considered critical or very important by 85% of responding prescribers, with 43% considering it critical, and 42% very important. This pattern was seen across most countries, although only 32% of responding prescribers from Brazil said it was critical and 53% said it was very important, while 39% of responding prescribers from Mexico said it was critical, 36% said it was very important, and a relatively high percentage (18%) thought it was only ‘somewhat important’. Very few prescribers (≤ 6%) in all countries combined found DAW only slightly important or not important at all.

In line with this, 87% of responding prescribers across all countries said they considered it was either critical or very important that they received notification if their patient had received a biological other than the one they had prescribed. Although most responding prescribers in all countries considered this either critical or very important, relatively high proportions of physicians in Colombia and Mexico (14% and 16%, respectively) thought it only ‘somewhat important’ to receive notification of a switch.

Limitations

It is important to remember that these data represent only a very small proportion of prescribers in each of these countries. Of the prescribers surveyed, i.e. 399 prescribers (6% response rate of the total sample size) from these four Latin American countries. This limits the ability to extrapolate results to the general population of physicians who prescribe biological products in these countries. Nevertheless, the results raise some important issues concerning the knowledge about and use of biological medicines.

The prescribing practices reported by the physicians who responded to this questionnaire survey varied across the region. It was clear that, among those who completed the questionnaire, there were important gaps in the understanding and use of distinguishable names for biologicals.

As many as 57% of respondents said they refer to a medicine exclusively by its non-proprietary name in their patients’ records, which could result in a patient receiving a different version of the medicine than the one prescribed. Additionally, few responding physicians said they report AEs associated with biological medicines and of these only 28% indicated that they use the non-proprietary name when reporting AEs, which could, in the absence of an identifying suffix, result in attribution to the wrong medicine, see Figure 2.

Those Latin American prescribers who completed this questionnaire overwhelmingly supported WHO’s BQ proposal, which would allow biosimilars to be clearly distinguishable from the reference products upon which they are based for purposes of clear prescribing, dispensing and long-term tracking of safety and efficacy [3].

|

Key points of the 2015 Latin American prescribers survey

|

The Alliance for Safe Biologic Medicines (ASBM) is an organization composed of diverse healthcare groups and individuals – from patients to physicians, innovative medical biotechnology companies and others – who are working together to ensure patient safety is at the forefront of the biosimilars policy discussion. The activities of ASBM are funded by its member partners who contribute to ASBM’s activities. Visit www. SafeBiologics.org for more information.

Disclosure of financial and competing interests: Harry L Gewanter, MD, FAAP, FACR, Chairman of the Alliance for Safe Biologic Medicines (ASBM), and Mr Michael S Reilly, Esq, Executive Director; are employed by ASBM.

This paper is funded by ASBM and represents the policies of the organization.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Michael S Reilly, Esq, Executive Director, Alliance for Safe Biologic Medicines

Harry L Gewanter, MD, FAAP, FACR, Chairman, Alliance for Safe Biologic Medicines

References

1. Azevedo VF, Galli N, Kleinfelder A, D’Ippolito J, Urbano PC. Etanercept biosimilars. Rheumatol Int. 2015;35(2):197-209.

2. Who Health Organization. Biological Qualifier. An INN proposal. June 2015 [homepage on the Internet]. 2015 Jun 4 [cited 2015 Nov 23]. Available from: http://www.who.int/medicines/services/inn/bq_innproposal201506.pdf.pdf?ua=1

3. GaBI Online – Generics and Biosimilars Initiative. WHO investigates use of a biological qualifier for biosimilars [www.gabionline.net]. Mol, Belgium: Pro Pharma Communications International; [cited 2015 Nov 23]. Available from: http://www.gabionline.net/Biosimilars/General/WHO-investigates-use-of-a-biological-qualifier-for-biosimilars

4. Giezen TJ, Schneider CK. Safety assessment of biosimilars in Europe: a regulatory perspective. Generics and Biosimilars Initiative Journal (GaBI Journal). 2014;3(4):180-3. doi:10.5639/gabij.2014.0304.041

5. Alexander EA. The biosimilar name debate: what’s at stake for public health. Generics and Biosimilars Initiative Journal (GaBI Journal). 2014;3(1):10-2. doi:10.5639/gabij.2014.0301.005

|

Author for correspondence: Michael S Reilly, Esq, Executive Director, Alliance for Safe Biologic Medicines, PO Box 3691, Arlington, VA 22203, USA |

Disclosure of Conflict of Interest Statement is available upon request.

Copyright © 2015 Pro Pharma Communications International

Permission granted to reproduce for personal and non-commercial use only. All other reproduction, copy or reprinting of all or part of any ‘Content’ found on this website is strictly prohibited without the prior consent of the publisher. Contact the publisher to obtain permission before redistributing.

Source URL: https://gabi-journal.net/prescribing-practices-for-biosimilars-questionnaire-survey-findings-from-physicians-in-argentina-brazil-colombia-and-mexico.html

Copyright ©2024 GaBI Journal unless otherwise noted.