Author byline as per print journal: Vito Annese, MD, PhD; Cristina Avendaño-Solá, MD, PhD; Professor Ferdinand Breedveld, MD; Niklas Ekman, PhD; Thijs J Giezen, MSc, PharmD, PhD; Professor Fernando Gomollón, MD, PhD; Research Professor Pekka Kurki, MD, PhD; Professor Tore Kristian Kvien, MD; Professor Andrea Laslop, MD; Professor Lluís Puig, MD, PhD; Robin Thorpe, PhD, FRCPath; Martina Weise, MD; Elena Wolff-Holz, MD

|

Introduction: Biological drugs are improving therapeutic options for many diseases, but access to these therapies is being held back by costs. Biosimilars offer a lower-cost alternative to the corresponding original therapeutic protein, the reference product, with a comparable quality, safety and efficacy. Despite these apparent advantages, arriving at the best solution for patients will need improved communication between regulators and caregivers. |

Submitted: 24 January 2016; Revised: 21 April 2016; Accepted: 21 April 2016; Published online first: 4 May 2016

Access to biological therapies, despite their clear potential for the treatment of many diseases, is more or less restricted owing to high cost. The problem is likely to continue or even aggravate, as a growing number of biological therapies enter the market. It remains unclear whether healthcare systems will be able to make these therapies widely available. Stakeholders hope that biosimilars will have a significant impact on the sustainability of future pharmacotherapy. Regulators and learned societies, especially medical societies, have prominent roles in guiding the rational use of new medicines, including biosimilars.

European regulators and medical societies were the first to encounter biosimilars, and countries worldwide are looking to Europe for guidance.

The Generics and Biosimilars Initiative (GaBI), with its mission to foster the worldwide efficient use of high quality and safe medicines at an affordable price, organized a roundtable discussion for European regulators and medical societies on biosimilars with the aim of promoting interaction and sharing information in this increasing important area. It is important to respect the expertise and role of each stakeholder in the biosimilar discussion, agree Research Professor and former Chair of the European Medicines Agency’s (EMA) Biosimilar Medicinal Products Working Party (BMWP), Pekka Kurki of the Finnish Medicines Agency, Fimea, and Chair of the Roundtable on Biosimilars, and Dr Robin Thorpe, Deputy Editor-in-Chief of the GaBI Journal, expert of BMWP, formerly Head of Biotherapeutics Group of the UK’s National Institute of Biological Standards and Control and Co-Chair of the Roundtable.

On 12 January 2016, GaBI held a Roundtable on Biosimilars in Brussels, Belgium, with participation by European regulators and medical societies. The programme offered speaker presentations and parallel discussion groups to provide participants with important and up-to-date information related to many aspects of biosimilars with a focus on the key issues of comparability, extrapolation, interchangeability and substitution, as well as pharmacovigilance. Presentations were in English. The speakers were regulators but not official delegates of any regulatory body.

Differences between regulatory decisions and the recommendations of medical societies

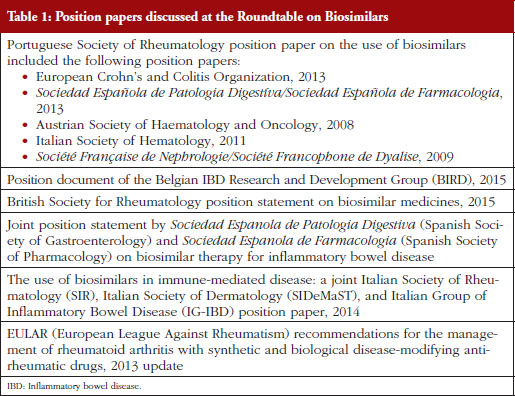

The Roundtable was opened by the Chair, Professor Pekka Kurki, expert of BMWP, with an overview of European Medical Societies’ position papers on biosimilars, see Table 1. Restricting the overview to recent papers that were written in English, he focussed on the concerns and contrasting views contained within these papers with regards to the regulatory decisions. With the growth in biological therapies and the numbers of diseases they treat, there is a steadily growing number of position papers.

Overall, Professor Kurki noted that these papers were generally in favour of biosimilars, particularly for new patients. But there were mixed opinions on extrapolation, traceability, interchangeability and automatic substitution. Prescribing by brand name was favoured, and there were concerns over immunogenicity.

The biggest problem for physicians, and therefore for medical societies, is that biosimilars can never be exact copies of their reference products. This was a point made throughout the Roundtable in spite of the fact that minor variation of the physicochemical properties of different versions of the same product is an inherent property of all biologicals. Physicians across the board do not find this straightforward to explain to patients. The problem is particularly evident in a naturally relapsing/remitting disease like rheumatoid arthritis (RA). A patient who starts taking a biosimilar and suffers a relapse of symptoms may well blame the symptoms on the biosimilar, and doctors might not always be confident explaining that this is unlikely – given the comparability studies to which each biosimilar will have been subject.

Professor Kurki noted that it is important to recognize that biosimilars have a proven similarity without being identical to the reference product. According to medical societies, even sophisticated comparability testing, in vitro assays and animal studies cannot fully predict the biological and clinical activity of a therapeutic monoclonal antibody.

According to some position papers, extrapolation of indications approved for the originator drug to completely different diseases and age groups that are not based on adequate preclinical, safety and efficacy data (ideally phase I and phase III trials) should not be performed. In their view, extrapolation from rheumatoid arthritis and ankylosing spondylitis studies to Crohn’s disease (CD) and/or ulcerative colitis (UC) cannot be done unless information on mucosal healing, corticosteroid-free remission or immunogenicity and loss of response in CD or UC patients is provided.

The same concerns apply to paediatric patients. Studies specifically looking at outcomes such as growth and development are welcomed by some medical societies.

One concern shared by all the position papers reviewed by Professor Kurki’s team, was that of physician autonomy. It was important for all medical societies that their physicians could make their own therapeutic choices. ‘That is understandable, and we support that. But there are economic realities, and the question is how to apply prescribing autonomy in the best way for the benefit to patients and healthcare systems,’ says Professor Kurki.

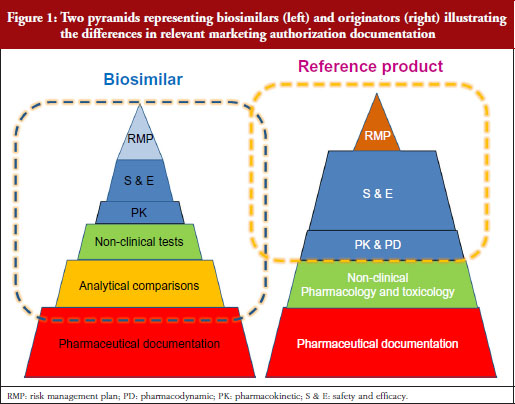

Professor Kurki showed a figure illustrating the difference in development philosophies between biosimilars and the reference product, see Figure 1. Two pyramids (representing biosimilars on the left, and originators on the right) represent the marketing authorization documentation. The pyramid representing biosimilars starts at the base with quality documentation (pharmaceutical documentation), followed by an extensive portion dedicated to comparative in vitro studies, analytical, functional and structural testing side-by-side, and then a limited set of clinical trials, and at the top, the risk management plan (RMP). This is clearly different for the development of a new active substance, he notes. While both pyramids share the pharmaceutical documentation, with standards exactly the same for biosimilars as for new biologicals, the originator also has to investigate the pharmacology, the mode of action and the toxicology of the product. For biosimilars, those are already known. Then there is an extensive set of studies for absorption, distribution, metabolism, elimination and pharmacodynamics (PDs). For biosimilars, it is sufficient to demonstrate a comparable exposure after single or repeated administration. In the case of a new biological, every claimed indication needs to be studied, alongside special groups such as children or patients with organ dysfunction. Finally, as with biosimilars, the RMP needs to be in place.

Our problem, suggests Professor Kurki, is that while the regulators look at the analytical and non-clinical testing and the clinical trials as one package (‘totality of evidence’) when deciding what is a biosimilar, clinicians focus on the clinical part only. This would explain, he suggests, the lack of confidence in comparability, while regulators seem more comfortable because they have been carrying out these studies for over two decades for manufacturing changes. This was discussed in more detail by Dr Niklas Ekman, also of Fimea.

Clinical biosimilar safety and efficacy studies look like typical phase III studies, but they are not; they have special features, e.g. looking at population pharmacokinetics (PKs) or PDs markers. Physicians see the active substance of biosimilar as new active substance, whereas regulators see it as a different version of the same active substance.

For specialists, it is difficult to accept that studies performed in one disease can be applied to another disease with different pathogenic features. Regulators, meanwhile, are more focussed on receptor binding and functional tests of the biosimilar, i.e. the mode of action of the active substance.

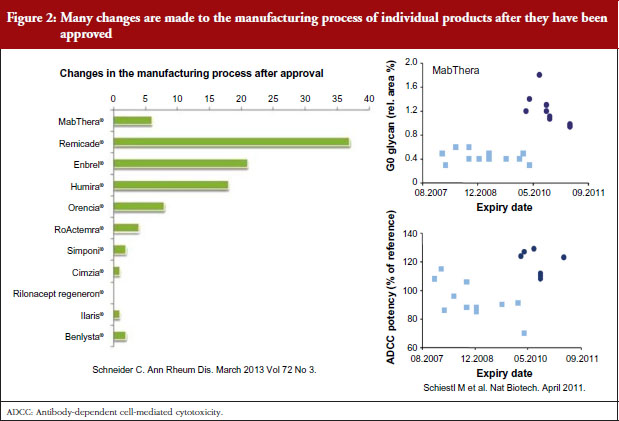

Manufacturing and characterization of biologicals

Dr Niklas Ekman, a member of EMA’s BMWP, explained how manufacturing process changes are common for all biologicals, both originators and biosimilars. He pointed to earlier studies showing the number of changes made to the manufacturing process of individual products since their approval [1], see Figure 2, and how manufacturing changes impacted on the glycosylation profile and antibody-dependant cell cytotoxicity (ADCC) of biopharmaceuticals – biopharmaceuticals that, from a physician’s point of view, would have been identical [2]. In other words, after a change in manufacturing process, originator biologicals are also not identical to earlier versions of the same originator biological. The comparability concept and its fundamental importance for the maintenance of safety and efficacy have remained unknown to physicians which may explain their reservations to biosimilars.

Clinical and non-clinical comparability

Professor Andrea Laslop of the Austrian Medicines Agency and a member of the EMA’s Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP), discussed clinical and non-clinical comparability for biologicals/biosimilars. The non-clinical development is based on the 3Rs: Reduce, Refine and Replace, animal studies as much as possible with in vitro data.

Comparability programmes at the clinical level can and must be strengthened by a number of factors, Professor Laslop urged. Comparability testing must use a homogeneous/sensitive population, a sensitive dose (or two doses), an appropriate model and statistical approach, and must use an accurate definition of the equivalence margin. The primary outcome measures need not be the same as those in the originator’s pivotal clinical trials. Orphan drugs raise unique challenges related to small population sizes. These challenges can be resolved in collaboration with regulatory authorities. Importantly, international dialogue between regulators is needed in order to encourage harmonization of regulatory requirements on a global scale. The final goal, says Professor Laslop, is to provide faster access for patients to affordable biological medicines at a sustainable price.

Immunogenicity

Dr Robin Thorpe, a member of EMA’s BMWP, focussed on the issue of immunogenicity. The European Union was the first to put together a guideline on immunogenicity assessment, he noted, and there is a revised version of this guideline due later in 2016. Immunogenicity issues occur all along the life cycle of a product, and particularly when a new therapeutic protein is developed and used for various clinical indications; when a change in process, formulation, or storage conditions is introduced or – notably given the topic of this roundtable – when a biosimilar product is proposed. Assessment requires an optimal antibody testing strategy alongside validated methodologies and reference standards. A better quality such as decreased immunogenicity does not preclude biosimilarity but needs to be justified as it possibly indicates a difference between products.

Extrapolation

Dr Martina Weise of the Federal Institute for Drugs and Medical Devices in Germany and Vice Chair of EMA’s BMWP discussed the principles of extrapolation of indications. Despite being the most contentious issue of biosimilar development, Dr Weise says extrapolation of indications is the single greatest benefit of biosimilar development.

Noting the data presented by Dr Niklas Ekman, see Figure 2, Dr Weise pointed out that extrapolation of data is already an established scientific and regulatory principle that has been exercised for many years, for example, in the case of changes in manufacturing process of originator biologicals. In such cases, clinical data are not required. In the development of biosimilars, clinical data are typically generated in one indication and, taking into account the overall information gained from the comparability exercise, may then be extrapolated to the other indications.

Dr Weise has recently published a paper on the science of extrapolation [3], with her regulatory colleagues, where the authors say they are not aware of any case of a change in the manufacturing process where more than one clinical study was required to compare two versions of the same product and this was sufficient for all approved indications.

Extrapolation must always be appropriately justified, and, where doubt remains, additional functional or clinical data are required for extrapolation to be granted. Dr Weise reminded delegates that scientific evidence and explanation of the reasons for extrapolation granted by CHMP may be found in the European Public Assessment Reports (EPARs).

Interchangeability

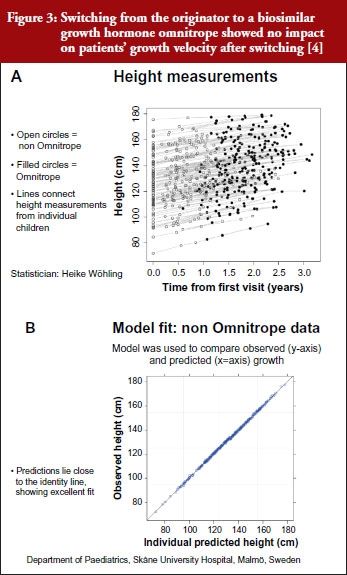

Dr Elena Wolff-Holz of Germany’s Federal Agency for Vaccines and Biomedicines, and a memberof EMA’s BMWP, discussed the interchangeability and substitution of biosimilars. She presented findings from a series of small to medium-sized switching studies involving biologicals and biosimilars, none of which showed any safety/efficacy signals that would justify extensive, longer studies.

For example, a Swedish study that investigated switching between the originator and biosimilar of the growth hormone (somatropin) showed no impact on patients’ growth velocity after switching to the biosimilar, see Figure 3 [4]. When a model was used to compare observed versus predicted growth, the predicted levels lay close to the observed data, showing excellent fit. Similar findings were shown for epoetin alfa-containing biosimilars, biosimilar filgrastim, biosimilar insulin glargine, and biosimilar infliximab. She also emphasized the value of EPARs (European Public Assessment Reports) in which results of biosimilars development programmes (epoetin, filgrastim, insulin glargine, somatropin), which included crossover trials with originators, are presented.

Referring back to the point made by Dr Niklas Ekman, see Figure 2, Dr Wolff-Holz reminded participants of the number of post-marketing changes made to biological drugs, notably monoclonal antibodies, without the need for further clinical studies. The regulators recalled only one case where clinical data were requested. The risk of rare adverse effects is best addressed by the RMP, as with any other medicinal product, she concluded.

Pharmacovigilance

Dr Thijs J Giezen, a hospital pharmacist at the Foundation Pharmacy for Hospitals in Haarlem, The Netherlands, and a member of EMA’s BMWP, discussed the safety assessment and risk management of biosimilars. Safety assessment is of paramount importance for biosimilars, with a particular focus on immunogenicity. Major differences in immunogenicity might question biosimilarity, he noted. As with all drugs, pharmacovigilance for originators and biosimilars is vital, and traceability is of specific importance.

When drawing up a pharmacovigilance plan for a biosimilar, post-marketing studies that not only compare safety profiles but also warn against rare adverse events are in a key position. Additional immunogenicity studies may be considered, perhaps in the context of studies that are already underway, for example, rheumatology registries, or – at a company’s own discretion – initiating new studies.

Physicochemical and functional comparability

It was asked whether the quality attributes of a biosimilar and its reference product will be compared in the same way as in the PK bioequivalence studies. It was clarified that, for the key quality attributes, the acceptable range is defined by the analysis of variability between batches of the reference product. For other quality attributes, the acceptable range depends on the type of analytical method. Therefore, statistical analyses are difficult to apply. The products are tested side-by-side to reduce variability. If differences are found, they will be judged by prior knowledge of previous analyses of different versions of proteins in the same class, analysing additional batches, and by using orthogonal methods to look at the same characteristics.

Impact of physicochemical and functional differences on safety and efficacy

Analytical comparability leans on the experience gained from studies of different versions of the active substance after a change of the manufacturing process. These changes are very common because the manufacturing processes need to be optimized, their scale is increased and manufacturing sites changed. Some participants were surprised by the variation between different versions of original biological products that have been accepted without clinical data. It was discussed whether clinical data should be requested more often before accepting a manufacturing change. The regulators responded that there is no evidence from clinical trials performed after licensing, such as expansion of therapeutic indications, that the safety or efficacy of current biotechnology-derived proteins would have changed over time significantly. The explanation is that analytical tests are more sensitive than clinical trials for showing differences.

The demonstration of comparability of monoclonal antibodies is challenging because they have several possible modes of action. Binding to the antigen is necessary for function but Fc-mediated functions may have a role as well. Nevertheless, all functions can be measured by in vitro analytical and functional tests. In the discussion, interpretation of these tests, especially the test for antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC) was discussed. The audience was concerned about the differences that have been demonstrated after manufacturing changes as well as differences between biosimilars and their reference products. In general, the role of Fc-mediated functions in the therapeutic effect is incompletely known. It was argued that it cannot be excluded that observed ADCC differences (~20%) have an impact on the efficacy or safety. Regulators responded that the differences often disappear when different effector and target cells are used or non-relevant antibodies are present. Sometimes the difference appears only in cells that have Fc-receptors with high affinity genotype. Glycosylation patterns that increase ADCC activity may have a clinical impact. Obinutuzumab is an anti-CD20 antibody that was glyco-engineered in order to enhance the binding to FcγRIIIa. As a result, its ADCC activity against different B-cell lines is 5- to 100-fold higher than that of the ‘wild type’ antibody. This antibody has been shown to be more effective than rituximab in depleting malignant B-cells in chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Against this background, the small difference in the ADCC between the first biosimilar infliximab and its reference product appears insignificant, especially when considering the applied ADCC test using a target cell line that has been genetically modified to be very sensitive for anti-tumour necrosis factor (anti-TNF) effects.

Interestingly, serious problems after manufacturing changes have been associated with the drug formulation rather than the active substance itself. Pure red cell aplasia (PRCA) has been triggered initially by factors in drug formulation but not with the epoetin alfa itself.

Does comparability mean therapeutic equivalence?

It was asked whether there are examples of seemingly perfect analytical comparability but observed clinical differences at the same time or later. More than 200 cases of PRCA were observed in patients treated with the marketed original epoetin alfa after a manufacturing change. Likewise, decreased efficacy and increased reactogenicity have been observed after manufacturing changes of a few vaccines. So far, such differences have not been observed with biosimilars after licensing. One case of PRCA was detected in a clinical trial with a biosimilar epoetin alfa in development. The development was discontinued. Thus, the experience from the reference product and the extensive comparability exercise will help to identify possible problems already in the development phase of a biosimilar.

Can a biosimilar be better than its reference product?

A product cannot be biosimilar if it has inferior safety or efficacy. However, what if the product is superior? A biosimilar may have an improved quality profile, e.g. purity and immunogenicity. Reduced immunogenicity may lead to slower loss of efficacy and, thus, better adherence to therapy by some patients. Thus, the applicant has to justify the difference with regard to safety and efficacy. Increased efficacy is not possible for a biosimilar since it would make it impossible to refer to the documentation of the reference product which is the basis of the abbreviated development. According to the EU legislation, a ‘biobetter’ must be licensed as a new active substance.

Immunogenicity

It was pointed out that, in the future, there will be several biosimilars for the same reference product. This may lead to multiple switches for the same patient over time. Multiple switches are often said to increase the risks of immunogenicity. Should this scenario be tested before licensing of a biosimilar? Regulators responded that immunogenicity of each biosimilar and its reference product will be compared before licensing. For the time being, data from switching biosimilars and the reference product are reassuring. The current view among European regulators is that, once comparable immunogenicity has been demonstrated against the reference product, there is no need to perform specific switching studies.

Extrapolation

How to select the patient population for a clinical efficacy and safety study when the product is used in different diseases and patient populations using different combinations with other products that may interfere with the performance of the tested active substance was also discussed. It was also asked whether all combinations and diseases and dosing regimens should be tested. Regulators clarified that clinical safety and efficacy studies were preceded by PK and PD studies. The developer should not proceed to large clinical trials if comparability is not demonstrated. The safety and efficacy studies should be done in a clinical model that is representative for other models, i.e. therapeutic indications and populations, and which is sensitive for showing differences. The purpose of the safety and efficacy studies is to complement and confirm the comparability demonstrated at the previous steps of development. This approach requires that the clinical endpoints are sensitive to differences. Thus, the primary clinical endpoints selected for demonstration of comparable efficacy are not necessarily the same as those used in the pivotal clinical trials of the reference product at the time of licensing. For example, overall survival rate and time to progression are generally used in oncology to study a product with a new active substance. These endpoints are time related and usually take rather long time for evaluation. Therefore, a more reasonable and sensitive endpoint, such as overall response rate, may be used. Thus, testing in all therapeutic indications, populations and drug combinations is neither necessary nor feasible.

Disagreements on extrapolation

The concern about extrapolation by clinicians is the use of the same biosimilar or a new innovative product, notably monoclonal antibodies, in different diseases in which the mechanism of action is thought to be different. Infliximab, for example, used in rheumatology is thought to act predominantly through the neutralization of soluble and trans-membrane TNFα, whereas in other conditions such as Crohn’s disease, signalling through membrane-associated forms of TNFα and Fcγ receptors that may trigger apoptosis or ADCC may play a more important role.

Regulators responded by pointing out that the different functions of a therapeutic monoclonal antibody are always investigated by in vitro receptor-binding and cell-based functional assays. These assays are more sensitive than clinical trials. Therefore, regulators feel more comfortable than clinicians with the extrapolation of safety and efficacy between different therapeutic indications.

Clinicians pointed out that clinical experience from less formal, e.g. open label, studies will and have already relieved some concerns about extrapolation.

Clinicians are puzzled by the fact that, in case of the first biosimilar infliximab, Canadian regulators, in contrast to their European colleagues, did not accept the extrapolation of safety and efficacy from RA to inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). Does the fact that all therapeutic indications of the reference product were granted in the EU and later by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) mean that the future biosimilar infliximabs, or even etanercepts, will get all therapeutic indications of the reference product automatically? The current regulatory view is that the extrapolation is considered on the basis of the comparability exercise of a given product together with the justification by the applicant. Thus, it is a case-by-case decision.

Regulators’ expectation is that biosimilars approved in the EU will have the same therapeutic indications as the reference product. This is desirable from the pharmacovigilance point of view since a restricted set of therapeutic indications may lead to off-label use. Sometimes, the applicant is not seeking for all therapeutic indications because of patents or because of the lack of suitable, e.g. paediatric, formulation.

Off-target effects and biosimilarity

In general, it is a constant feature of clinical science to observe results that were not expected on the basis of previous knowledge. This is, indeed, almost always the situation after licensing of a product containing a new active substance. It was discussed whether unexpected off-target effects could be observed with biosimilars.

The regulators argued that biologicals, by their nature, have less off-target effects than chemicals. The long experience with the reference products helps to understand the effects of the active substance. A biosimilar will have the same effects, both beneficial and adverse, as the reference product. For biosimilars, the issue is whether new, unexpected off-target effects could be encountered in spite of the extensive comparability exercise. The discussion led to the topic of whether a comparable receptor interaction is sufficient to predict similar functional effects or whether differences in the downstream signalling pathways in target cells could be significantly different after the binding of the biosimilar and the reference product in spite of comparable results in functional cell-based tests, e.g. phagocytosis, apoptosis, ADCC. Regulators maintained that it is essential to separate the effects of the product from the responses of different types of target cells that may respond differently to the same signal. In the end, no agreement was reached on the significance of off-target effects with the use of biosimilars.

A possible off-target effect was mentioned in the context of cancer therapy and bone marrow after treatment with biosimilar filgrastim. Reference was made to the study of Brito et al. (Support Care Cancer. 2016; 24(2):597-603) in early breast cancer receiving (neo)adjuvant docetaxel/doxorubicin/cyclophosphamide therapy and prophylaxis with biosimilar, pegfilgrastim or reference filgrastim. The treatments were administered at different consecutive time periods and data were gathered retrospectively. The rate of febrile neutropenia (FN) per patient and treatment cycle was the same in biosimilar and reference filgrastim groups. The rate of FN and severe neutropenia (ANC < 100 cells/μL) was seen in 50% of patients in the biosimilar group but only in 4% in the reference product group. The authors concluded that ‘No differences in biosimilar effectiveness were detected. The clinical relevance of the profound neutropenia found in the biosimilar cohort needs further attention’. Interestingly, no such difference was found in the multicentre, double-blind, therapeutic equivalence study of biosimilar G-CSF versus the reference product in subjects receiving doxorubicin and docetaxel as combination therapy for breast cancer.

Interchangeability

There is some concern in the rheumatology community about the long delay of full publication of the safety results of the long-term extension of the pivotal safety and efficacy studies of the first biosimilar infliximab, especially the study in ankylosing spondylitis (PLANETAS). During the extension, ankylosing spondylitis patients were switched from the reference product to the biosimilar. The switched patients had a higher rate of adverse events and more withdrawals from the therapy. These results have been reviewed by the EU regulators who did not react to the difference, probably because of the relatively small number of patients at the time of the switch and lack of a plausible explanation. A publication featuring the safety data after the switch is pending.

It was pointed out that neither regulators nor prescribers across the Atlantic have a uniform opinion of the interchangeability. This is partly due to different regulatory frameworks in the two areas and partly due to the interpretation of the theoretical basis and available data.

In the EU, interchangeability is within the mandate of the Member States whereas in the US, interchangeability studies are mandatory by legislation. Interestingly, FDA has not published any guidance on how to study interchangeability. This may reflect the scientific problems related to the switching studies.

Pharmacovigilance

It is evident that the root cause of some adverse effects of biologicals, notably immunogenicity, is in the improper handling and storage of biologicals. It is particularly important to maintain the cold chain. This is becoming a challenge also in Europe when the administration and storage of biological medicines is more and more often taking place at home by the patient or caregiver. Innovative auto injectors and packages may mitigate this problem in the future for biologicals, including biosimilars.

The Roundtable ended with three parallel discussion groups, each of which included representatives from regulatory authorities and from medical societies. Groups were asked to discuss physicians’ attitudes to and concerns surrounding biosimilars – comparability, immunogenicity, extrapolation, interchangeability and substitution, as well as pharmacovigilance. Focus discussion topics included the thought process in preparing position papers, the bottlenecks, e.g. training, and the concerns and challenges faced.

Group 1 Summary

Summarized by Professor Fernando Gomollón, MD, PhD; presented by Professor Ferdinand Breedveld, MD

Group 1 identified a remaining doubt among clinicians, which could be reflected in the question: do in vitro tests really predict the appropriateness of extrapolation? After recognizing that this mere concept can be difficult to accept for clinicians, the general agreement of the group was that if a multiple set of well standardized tests, enough data on exposure in a sensible population and previous clinical data are all considered, extrapolation can be seen as a good concept, a real change of paradigm.

Some issues were raised about safety signals in PLANETAS data. For some people, safety data may require more clarification, although the general opinion was that if EMA had considered the signals as non-significant, they were probably not important.

Registries

There was general agreement among group members on the importance of registries. Ideally these should function on a national scale with a core of data that is easy to share between countries. More work on the definition of these registries is clearly needed.

A real philosophical (or pathophysiological, if preferred) question was also raised. Would a knowledge of the exact mechanism of action of a drug in a given disease make it easier to extrapolate? Perhaps in theory, but with the mechanisms of these diseases being so complex, the general agreement is that the EMA road to extrapolation is adequate in the current state of knowledge.

Good research, poor communication

Some open discussion was undertaken on the low opinion that clinical gastroenterologists have for biosimilars (although it seems rather clear that things are changing and opinions improving). The general agreement was that EMA has done really good scientific work with biosimilars, but not communicated their findings effectively. So, communications should be improved and coordinated, with contributions from EMA, scientific societies and other authorities.

Improving patient care

The group found two concepts that needed emphasizing: 1) biosimilars are not easy to approve in Europe; 2) to date, after approval, the safety record of biosimilars in Europe is really quite good (if not excellent).

Finally, the group agreed that cost is the main drive for biosimilars introduction. This should be seen as an opportunity for better patient care, and that negotiation between payers, authorities, clinicians, pharmacists and patients is the best way to implement change.

Group 2 Summary

Summarized by Cristina Avendaño-Solá, MD, PhD; presented by Vito Annese, MD, PhD

In a group that included four regulators, two rheumatologists, two gastroenterologists, one haematologist and one clinical pharmacologist, there was full agreement on the opportunity that biosimilars provide both in increasing accessibility to biological medicines and in decreasing costs. Those costs can then be diverted to other health spending. Cost benefits are, however, more likely to be related to the arrival of competition, which will drive down the price of the originator drugs. Another possible bonus of biosimilars is seen in preliminary data suggesting that biosimilars could be improvements on originators. They might have less impurities, reduced immunogenicity, or be administered by improved devices.

Switching

One concern shared by the group was how to introduce biosimilars in clinical practice. It is difficult to promote switching between originators and biosimilars in a chronically ill patient who is already taking the originator.

There is still some reluctance about the comparability exercise based on a limited number of parameters and limited clinical data. Recognition of the contribution of data post-authorization and the importance of pharmacovigilance are key.

Concerns were raised about interchangeability. There were doubts related to the absence of data and the potential impact of switching on individual patients. It is complicated to demonstrate interchangeability.

There were also concerns about multiple switching and how to preserve pharmacovigilance and immunogenicity monitoring of each specific product.

Benefits of cost cutting

The group recommended increasing the visibility of the usefulness of the money saved through biosimilars. For example, the agreement of using biosimilars in IBD could go hand-in-hand with actions such as providing extra nurses, support to registers and support for therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM). It is important to recognize the value of TDM to guide switching.

Group members recommended revising how systems of price and reimbursement decisions work at the country level. Involving patients in decision-making will increase their awareness of the benefits of biosimilars.

Group 3 Summary

Summarized and presented by Professor Lluís Puig, MD, PhD

Group 3 focused on monoclonal antibodies for the treatment of immune-mediated inflammatory diseases (IMIDs).

The question was raised whether biosimilars will remove inequity of access to expensive drugs. Group members agreed that access should not depend on price. The UK’s National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) is working to facilitate entry of biosimilars into the market, but faces many obstacles and concerns among patients and clinicians who are dealing with the unknown.

Switching

The group recognized opposition to switching in patients who are doing well. The only reason for them to switch would be cost, and the group discussed the importance of cost, budgeting and patients’ say. Problems arise around the issue of enforced switching without patients’ consent and full knowledge of safety, or physicians’ choice. The pressure is clearly on the physician. In oncology and haematology there is particularly low acceptance of switching.

The question was raised whether switching trials are needed. Available results show no significant change, but perhaps they are unlikely to do so given their design and power limitations.

In Denmark, there is a 69% discount on Remsima, and authorities enforced wholesale switching. Wholesale switching was similarly promoted in Austria.

NOR-switch is a study funded by the Norwegian Government, aimed to compare the originator infliximab (Remicade) and Celltrion’s biosimilar infliximab (Remsima) as regards disease worsening rates across all indications after one year of treatment. Thirty per cent is the expected worsening rate of Remicade, 15% the non-inferiority margin, and 500 patients are the population enrolled.

Safety

The issue of safety monitoring and the need for registries was discussed. The group raised doubts on quality of monitoring, and asked who will pay for it. In most countries it is unrealistic that governments will pay for monitoring.

In the UK, NICE made a formal requirement that prescribers included new patients treated with biosimilars into registries. There is a need for tracking. There is a need to collect the data regardless of how likely it will be to see a result. There are huge methodological challenges with registries.

Extrapolation

The group looked at real-life data from the Czech Republic showing no difference between originators and their biosimilars. The same was shown for paediatric indications. Regulators do not care so much about the disease in which the trials are being made.

There is a very large difference in perception and acceptance between individual countries. In the Czech Republic, physicians today have no objection to switching and extrapolation based on their results. The situation has changed in 2015, based on education and experience.

Biosimilarity exercise

The group discussed how subjects for clinical trials of biosimilars cannot be found in Western Europe; they have early access to potent therapy and do not progress to levels of activity making them eligible for enrolment. Furthermore, the ethics of a clinical trial that does not provide a clinical advantage was discussed.

There was a concern that PK studies in healthy volunteers may not be representative for all indications in which PK may vary. The regulatory view is that the variability in patients is more dependent on confounding factors than on the active substances.

A request was made for further detail or transparency in preclinical data. An understanding of the way regulatory agencies make their decisions is needed, rather than calling for ever-increasing numbers of clinical trials.

It was concluded that biosimilars have the potential to increase patients’ access to biological therapy. Clinicians keep asking for more data and tailored information, especially on the safety and practical conduct of the switches between the biosimilar and its reference product. There is a consensus on the need for a better traceability and surveillance of adverse events of all biologicals. Physicians would like to see data of biosimilars in new or established registries.

Information and transparency are the key issues. It is not only data, as information is available, but only scarce information that is tailored towards different groups of stakeholders. Prescribers, maybe even different specialities, need different information, patients, hospital pharmacists and maybe payers as well. This is one of the take home messages – not only for regulators. Regulators will certainly give a signal to agencies and EMA that the emphasis on information should be even more than it is today.

This information should not only be tailored to the different stakeholders, it also should be focused on certain issues. Information available on several interesting factors can be put together as needed for each stakeholder. One of the issues that has been raised is whether physicians can explain the comparability exercise, especially the physicochemical in vitro biological aspect, and how decision-making is based on those tests.

Prescribers need information on extrapolation, they need to explain why therapeutic indications have been granted without clinical trials. This is another message that delegates at the Roundtable will need to bring back to their organizations and agencies.

The structure–function relationship, what can be said from individual results of analysis, how it can be concluded that a difference in an analytical test is not important, all needs to be explained to patients.

The Chair added one particular target for information, namely extrapolation of safety and efficacy. There are not enough regulators to explain to all stakeholders what extrapolation is, what analytical testing is, and so on. This has to be a collaborative exercise. The information received from London or from Brussels, prepared by multi-disciplinary multi-national teams, is very complicated. This information needs to be tailored according to national healthcare providers and society in general.

Physicians at the meeting were of the opinion that the information on the whole development cascade has helped to put the difficult issues, such as extrapolation and interchangeability, into a clearer context. Yet the limited data on the difficult topics, especially on interchangeability, is still of concern.

The presentation on the physicochemical and structural as well as in vitro functional analyses as the basis for comparability of different versions of both the original and biosimilar products and the long experience of these studies helped clinicians understand the concept of biosimilarity. The fact that the original biological products are not, from a physicochemical point of view, the same as at the time of licensing – because they have been subject to many manufacturing changes over their life cycle – was surprising to some delegates. One delegate even went on to say that it was a shame that physicians had not been aware of the manufacturing process change data shown by Dr Niklas Ekman and others, see Figure 2, which might have made switching to biosimilars less worrying. Any differences in a drug are feared, but it is now clear that physicians have been prescribing non-identical versions of the same drug for years.

Perhaps not surprisingly, the group discussions all agreed that the position of the physician is a difficult one when switching patients from the original product to the biosimilar. Physicians must keep up to date with the latest data in this area, and are personally accountable to their patients for their treatment decisions. On one hand, clinicians do not have the possibility to judge all data that were available for regulators at the time of marketing authorization. On the other hand, positive experience from some members of the groups reduced the level of uncertainty and anxiety.

It is not easy for a physician who has had success with an originator drug to switch to a biosimilar for cost reasons. It may be difficult to persuade a patient to switching to an alternative drug because it is cheaper, rather than because it is better. The health service overall stands to gain through cost savings, not the individual patient. Therefore, switching plans should incorporate some extra values for the patients, increasing their awareness of the benefits of biosimilars.

In at least two discussion groups, it became clear that Czech physicians are relatively unconcerned by switching. This was attributed to a successful education campaign, and to not being under cost pressures. Physicians from other countries often described how they felt they were being put under pressure to make cost savings from which they and their patients would not directly benefit. Perhaps learning about biosimilars and what they are, before being put under pressure to cut costs, would have made switching easier to deal with.

Conflict of interest was mentioned in the discussions. Biosimilarity is an area with high commercial interest. The regulators have extremely stringent rules for conflict of interest. Such rules are not possible in the clinic because it would be very difficult to run clinical trials. Nevertheless, relationships with industry should be somehow managed in order to maintain credibility. This is an issue that both regulators and prescribers need to be very much aware of.

The post-marketing follow-up is another area where physicians and regulators have common interests, especially how to make the most of registries. Current registries have been useful but there have been clear drawbacks; they are not available in every country, the ones that exist are useful for certain purposes but they are not compatible with each other, and it can be difficult to get information by pooling the data from different registries.

The national agencies should consider ways to contribute to registries. There are economic issues; who will fund the registries, how will the people who maintain it be reimbursed? This is also a political issue, since people are sensitive with their information/personal data and hence, permission from the patient is needed to use the data. This is an area where collaboration is required, including a strong signal from clinicians and regulators that these data are important for health care and for individual patients.

Traceability was discussed in the context of having several biosimilars, price competition and tendering processes. This situation may lead to multiple switches that should be documented. TDM was considered slightly outside the typical regulatory scope. There is some information in the summary of product characteristics if the company has been able to provide the necessary information. However, usually this is not the case and TDM is more for academics and clinicians who develop these systems.

Costs were not included in the presentations of this meeting although there is no other incentive to use biosimilars than lower price/costs. Physicians may have to change their role in the biosimilar discussion. The positive consequences of the price competition that is triggered by biosimilars needs to be understood. Roundtable Chair Professor Pekka Kurki hoped that delegates did not mind this kind of remark: ‘Economics are there and times will not improve, it will be harder in the future,’ he said. Instead of maintaining a very conservative attitude, there is another option to become active and try to get the best out of this situation, he said. ‘Think what you can do to induce cost savings with your prescription behaviour. There are examples, from the Czech Republic and the UK, as to how biosimilars can help save money that can be used for other purposes.’

The Roundtable Chair concluded that the pleasant and constructive atmosphere of the meeting supported fruitful discussions, and testified for the importance of dialogue between regulators and physicians. Dialogue increases the mutual trust that is needed when new products and concepts are introduced to health care. The story of biosimilars is not yet at its end, this meeting was an interim analysis. Stakeholders need to be vigilant as the story unfolds.

It appears that the information on biosimilars has not been sufficient to satisfy the needs of prescribers. Physicians were interested in the way physicochemical, structural analyses and in vitro functional tests are used to demonstrate comparability and in the definition of acceptable differences. EPARs contain valuable information on biosimilars. However, their value for clinicians would increase if the crucial decisions such as extrapolation would be better justified. The European regulatory network, EMA and national regulatory agencies, need to find solutions to fill the obvious information gap.

Most of the position papers of medical societies were quite conservative and some contained requirements that would make the development of biosimilars unfeasible. It is evident that prescribers and regulators have different understanding of the biosimilar concept. The situation is changing since more information has become available and since experience from countries that have introduced biosimilars in massive scale, including switches, has been reassuring.

As a consequence, biosimilars are seen more often as an opportunity than a threat. A new situation is emerging in which regulators and prescribers can collaborate in planning managed switches and in tailoring information to various stakeholders, patients, pharmacists, payers. Pharmacovigilance was recognized as an important field of collaboration. Adverse effect reporting of biologicals, including the batch numbers, should be intensified. Collaboration between and within healthcare centres and hospitals as well as pharmacies is necessary to ensure traceability and early detection of rare adverse effects. Regulatory authorities may be able to promote the use of registries in monitoring the use of biosimilars.

Prescribers are in an uncomfortable situation when planning switches in individual patients who will not get immediate benefit and who may have concerns in using biosimilars instead of the original product. Payers and hospital administration should consider granting some incentives to healthcare units that will introduce biosimilars to their patients, e.g. the possibility to use the saved money to improve patient care by introducing new therapies.

Closing the meeting, Co-Chair Robin Thorpe explained that an event like this could only be the first step to reaching a consensus. The strength of such a Roundtable format allowed stakeholders from different and sometimes opposing camps – physicians (rheumatologists, gastroenterologists, dermatologists, haematologists, oncologists), pharmacists and regulators – to discuss their principles and concerns openly. Any conclusions from the event can only reflect what was agreed at the meeting, and what was not agreed.

Speakers

Niklas Ekman, PhD, Finland

Thijs J Giezen, MSc, PharmD, PhD, The Netherlands

Research Professor Pekka Kurki, MD, PhD, Finland (Chair)

Professor Andrea Laslop, MD, Austria

Robin Thorpe, PhD, FRCPath, UK (Co-Chair)

Martina Weise, MD, Germany

Elena Wolff-Holz, MD, Germany

Moderators and Co-moderators

Vito Annese, MD, PhD, Italy

Cristina Avendaño-Solá, MD, PhD, Spain

Professor Ferdinand Breedveld, MD, The Netherlands

Professor Fernando Gomollón, MD, PhD, Spain

Professor Tore Kristian Kvien, MD, Norway

Professor Lluís Puig, MD, PhD, Spain

Participants

Miguel Angel Abad Hernandez, MD, Spain, Spanish Society of Rheumatology (SER)

Vito Annese, MD, PhD, Italy, Italian Group for the Study of IBD (IG-IBD)

Professor Federico Argüelles-Arias, MD, PhD, Spain, Spanish Society of Gastroenterology (SEPD)

Cristina Avendaño-Solá, MD, PhD, Spain, Spanish Society of Clinical Pharmacology (SEFC)

Professor Jürgen Braun, MD, Germany, German Society for Rheumatology (DGRh)

Professor Ferdinand Breedveld, MD, The Netherlands, European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR)

Professor Antonio Costanzo, MD, Italy, Italian Society of Dermatology (SIDeMaST)

Professor Maurizio Cutolo, MD, Italy, European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR)

Assistant Professor Marc Ferrante, MD, PhD, Belgium, European Crohn’s and Colitis Organisation (ECCO)

Professor Fernando Gomollón, MD, PhD, Spain, European Crohn’s and Colitis Organisation (ECCO)

Professor Dr Richard Greil, MD, Austria, Austrian Society of Hematology and Medical Oncology (OeGHO)

Barney Hawthorne, DM, UK, British Society of Gastroenterology (BSG)

Ana Hidalgo-Simon, MD, PhD, UK, European Medicines Agency (EMA)

Professor Tore Kristian Kvien, MD, Norway, European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR)

Professor Milan Lukáš, MD, PhD, Czech Republic, Czech Society of Gastroenterology (CSG)

Professor Alexander MacGregor, MD, PhD, UK, British Society for Rheumatology (BSR)

Professor Massimo Massaia, MD, Italy, Italian Society of Experimental Hematology (IESS)

Associate Professor Dan Nordström, MD, PhD, Finland, Finnish Society of Rheumatology (FSR)

Marieke Pereboom, PharmD, The Netherlands

Bea Perks, PhD, UK

Professor Roberto Perricone, MD, Italy, Italian Society for Rheumatology (SIR)

Laura Pirilä, MD, Finland, Finnish Society of Rheumatology (FSR)

Professor Lluís Puig, MD, PhD, Spain, European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology (EADV)

Riccardo Saccardi, MD, Italy, Italian Group for Bone Marrow Transplantation (GITMO)

Professor Maria-Jesús Sanz Ferrando, PhD, PharmD, Spain, Spanish Society of Pharmacology (SEF)

Lasia Tang, BSc, MBA, Belgium

Apologies

Gonzalo Calvo, MD, PhD, Spain, European Association of Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics (EACPT)

Professor Marco Matucci Cerinic, MD, PhD, FRCP, honfbsr, Italy, Italian Society for Rheumatology (SIR)

Professor Silvio Danese, MD, PhD, Italy, European Crohn’s and Colitis Organisation (ECCO)

Professor João Eurico Cortez Cabral da Fonseca, MD, PhD, Portugal, Portuguese Society of Rheumatology (PSR)

Professor Maurizio Vecchi, MD, Italy, Italian Group for the Study of IBD (IG-IBD)

The Generics and Biosimilars Initiative (GaBI) wishes to thank Research Professor Pekka Kurki for his strong support through the offering of advice and information during the preparation of this Roundtable meeting.

The authors would like to acknowledge the help of all the roundtable speaker faculty and participants, each of whom contributed to the success of the meeting and the content of this report as well as the support of the moderators: Dr Vito Annese, Dr Cristina Avendaño-Solá, Professor Ferdinand Breedveld, Professor Fernando Gomollón, Professor Tore Kristian Kvien and Professor Lluís Puig, in facilitating meaningful discussion during the parallel group discussions, and presented the discussion findings at the meeting.

The authors wish to thank Dr Bea Perks, GaBI Journal Editor, in preparing this meeting report manuscript and providing English editing support on the group summaries and for finalizing this manuscript.

The PLANETAS and PLANETRA extension studies including full safety data have been published online in Annals of Rheumatic Diseases after the meeting of Roundtable on biosimilars with European regulators and medical societies: Park W, et al. Efficacy and safety of switching from reference infliximab to CT-P13 compared with maintenance of CT-P13 in ankylosing spondylitis: 102-week data from the PLANETAS extension study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016;0:1-9. doi:10.1136/annrheumdis-2015-208783

Yoo DH, et al. Efficacy and safety of CT-P13 (biosimilar infliximab) in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: comparison between switching from reference infliximab to CT-P13 and continuing CT-P13 in the PLANETRA extension study. Ann Rheum Dis 2016;0:1-9. doi:10.1136/annrheumdis-2015-208786

Competing interests: The Roundtable meeting was sponsored by an unrestricted educational grant to GaBI from Hospira UK Ltd.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; internally peer reviewed.

Vito Annese, MD, PhD

Cristina Avendaño-Solá, MD, PhD

Professor Ferdinand Breedveld, MD

Niklas Ekman, PhD

Thijs J Giezen, MSc, PharmD, PhD

Professor Fernando Gomollón, MD, PhD

Research Professor Pekka Kurki, MD, PhD

Professor Tore Kristian Kvien, MD

Professor Andrea Laslop, MD

Professor Lluís Puig, MD, PhD

Robin Thorpe, PhD, FRCPath

Martina Weise, MD

Elena Wolff-Holz, MD

References

1. Schneider CK. Biosimilars in rheumatology: the wind of change. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013 Mar;72(3):315-8.

2. Schiestl M, Stangler T, Torella C, Cepeljnik T, Toll H, Grau R. Acceptable changes in quality attributes of glycosylated biopharmaceuticals. Nat Biotechnol. 2011;29(4):310-2.

3. Weise M, et al. Biosimilars: the science of extrapolation. Blood. 2014;124(22):3191-6.

4. Flodmark CE, et al. Switching from originator to biosimilar human growth hormone using dialogue teamwork: single-center experience from Sweden. Biol Ther. 2013;3:35-43.

5. GaBI Online – Generics and Biosimilars Initiative. Norwegian study may be slowing adoption of biosimilar infliximab [www.gabionline.net]. Mol, Belgium: Pro Pharma Communications International; [cited 2016 Apr 21]. Available from: www.gabionline.net/Biosimilars/News/Norwegian-study-may-be-slowing-adoption-of-biosimilar-infliximab

|

Author for correspondence: Research Professor Pekka Kurki, MD, PhD, Finnish Medicines Agency, PO Box 55, FI-00034 Fimea, Finland |

Disclosure of Conflict of Interest Statement is available upon request.

Copyright © 2016 Pro Pharma Communications International

Permission granted to reproduce for personal and non-commercial use only. All other reproduction, copy or reprinting of all or part of any ‘Content’ found on this website is strictly prohibited without the prior consent of the publisher. Contact the publisher to obtain permission before redistributing.

Source URL: https://gabi-journal.net/roundtable-on-biosimilars-with-european-regulators-and-medical-societies-brussels-belgium-12-january-2016.html

Author byline as per print journal: Steven Simoens, PhD; Claude Le Pen, PhD; Niels Boone, PharmD; Ferdinand Breedveld, MD, PhD; Antonella Celano; Antonio Llombart-Cussac, MD, PhD; Frank Jorgensen, MPharm, MM; Andras Süle, PhD; Ad A van Bodegraven, MD, PhD; Rene Westhovens, MD, PhD; Jo De Cock

|

Introduction/Objectives: This manuscript aims to provide guidance to policymakers with a view to fostering a fair, competitive and sustainable market for off-patent biologicals and biosimilars in Europe. |

Submitted: 6 June 2018; Revised: 13 July 2018; Accepted: 13 July 2018; Published online first: 20 July 2018

Reference biologicals are originator medicinal products made by or derived from living organisms using biotechnology. When the patent and exclusivity rights on a reference biological expire, biosimilar medicines can enter the market. A biosimilar is a biological product that contains a version of the active substance of an already authorized reference biological medicinal product [1]. On the one hand, the European Medicines Agency (EMA) and regulatory authorities guarantee the quality, safety and efficacy of registered biosimilars. After a decade of experience with biosimilar products, no unexpected concerns have emerged [2, 3]. Also, health economists of international organizations refer to the important savings potential of a competitive off-patent biologicals and biosimilars market and to the opportunity to improve patient access. On the other hand, the market access, uptake and price evolution of off-patent biologicals and biosimilars stay heterogeneous between countries and between therapeutic classes, e.g. erythropoiesis-stimulating agents, granulocyte colony-stimulating factors, human growth hormones, antitumour necrosis factors, follitropin alfa and insulins [4].

This implies that European countries are not realizing the full potential of the off-patent biologicals and biosimilars market. In this respect, the European Commission and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) have argued that competition in the off-patent biologicals and biosimilars market could yield substantial savings to healthcare systems [5, 6]. To capture these savings, the European Commission (Directorate-General for Internal Market, Industry, Entrepreneurship and small and medium-sized enterprises [SMEs]) has supported a multi-stakeholder approach and has hosted multiple workshops with a view to facilitating access to and uptake of biosimilars [7, 8]. The European Commission also issued a consensus information paper in 2013, an information document for patients in 2016, and an information guide for healthcare professionals in 2017 [8].

However, the development of a competitive market for off-patent biologicals and biosimilars is not certain because of numerous factors including the risk of non-recognition of the difference between biosimilars and generics, physician and patient lack of confidence, and unbalanced payer pricing and procurement policies. In particular, after a decade of experience with these products, it seems clear that a simple logic whereby price reductions multiplied by prescribed volumes of reference biologicals will lead to potential savings is misleading and inappropriate. Price reductions alone do not appear to be the key factor guaranteeing greater market penetration of biosimilars [4]. On the contrary, price reductions can lead to a race to the bottom, preventing manufacturers to enter the market.

It is also important that policymakers keep in mind that biosimilars (where the reference product is a biological medicine) are inherently different from generics (where the reference product is a chemically synthesized medicine), due to their more elaborate size and structure of the molecule, higher risks and costs of research and development, more complex manufacturing processes, extended development times, and the need to institute post-marketing pharmacovigilance programmes [9]. Therefore, policy must be adapted to the specific needs of the off-patent biologicals and biosimilars market.

Developing a competitive market for off-patent biologicals and biosimilars in Europe is a necessary condition for stakeholders to reap the benefits that such competition may create. These benefits include more control of drug expenditure for healthcare payers, expanded access to health care for patients, increased treatment choices for physicians, and headroom for innovation for industry. The development of such a market requires the implementation of a long-term, sustainable and specific policy framework based on a multi-stakeholder approach. Thus, the aim of this manuscript is to provide guidance to policymakers with a view to fostering a fair, competitive and sustainable market for off-patent biologicals and biosimilars in Europe, taking into account the role of all stakeholders.

This manuscript has been commissioned by the Belgian National Institute for Health and Disability Insurance. Individuals and stakeholder representatives from patient groups, clinicians, healthcare professional organizations, government bodies, and industry have participated in a series of roundtable discussions in 2016–2017 which have contributed to the development of the manuscript. These discussions were held under Chatham House Rules. This manuscript represents the authors’ views on the topic which have been informed by their participation in the roundtable discussions and do not represent the position of their respective organization/institution.

When developing guidance to policymakers, the focus of this manuscript is specifically on those product classes for which patent expiry and loss of exclusivity has recently occurred or is imminent, such as monoclonal antibodies for the treatment of inflammatory diseases (rheumatoid arthritis, inflammatory bowel diseases, psoriasis) and cancers.

Supply-side incentives

A building block of a fair, competitive and sustainable market for off-patent biologicals and biosimilars in Europe, see Box 1, relates to the need to put in place appropriate supply-side incentives. In particular, policymakers need to design smart procurement and reimbursement mechanisms with a view to allowing physicians to prescribe off-patent biologicals and biosimilars based on scientific evidence and clinical experience. The design of such mechanisms needs to be anchored in good clinical practice, which will evolve with knowledge, and needs to respect the European legislative framework on public procurement [10, 11]. Physician involvement in procurement and reimbursement mechanisms is vital to ensure that physicians maintain the freedom to prescribe. Also, there is a need to build up technical and practical expertise, and exchange experiences between countries with respect to designing smart procurement and reimbursement mechanisms.

Box 1: Recommendations for developing policy on off-patent biologicals and biosimilars in Europe

In the hospital setting, tendering mechanisms, i.e. public procurement mechanisms for medicines based on competition between pharmaceutical suppliers [12], can be applied to off-patent biologicals and biosimilars nationally or locally, although future studies need to provide guidance to policymakers on how to optimize the features of these mechanisms, such as the frequency of tenders, the criteria to grant the tender, the reward for the winner(s), and the number of winners. For example, tendering may lead to a market where only one medicine is available, i.e. the ‘winner takes all’ principle, and shortages may occur if that supply fails. Thus, tendering mechanisms need to be monitored to ensure that several pharmaceutical suppliers participate and that the market does not fail [13].

In the ambulatory care setting, off-patent biologicals and biosimilars can be included in a reference pricing system, which sets a common reimbursement level for a group of medicines. Policymakers need to appreciate that the application of a reference pricing system could imply that off-patent biologicals and biosimilars included in the same reference group could be used interchangeably (which indicates that a patient can be alternated between products whilst expecting the same clinical outcomes in respect to efficacy and safety as if no alternation were to occur) [14]. In such cases, the relevant policymaker should clarify the status of the medicine.

If implemented, smart tendering mechanisms and/or reference pricing systems need to be sufficiently flexible to permit the prescribing physician to act in the best interests of the patient, including the availability of choice between products. In our opinion, this also implies that physicians are in charge of any switching protocols and that no forced switching occurs. Although procurement and reimbursement mechanisms may generate price competition and produce short-term savings, policymakers also need to consider the possible impact of these mechanisms on the sustainability and the level of competition in the market for off-patent biologicals and biosimilars in the long run.

Demand-side incentives

In our opinion, a key challenge relates to how physicians should use off-patent biologicals and biosimilars in real-life, clinical practice. It is clear that biosimilars can be administered to treatment-naïve patients in all approved indications. However, there is debate and concern about whether it is appropriate to introduce incentives that encourage patients to be switched from a reference biological product to a biosimilar; from one biosimilar to another biosimilar; and about switching on multiple occasions. Although such incentives purport to encourage price competition between manufacturers, there remains residual uncertainty and resistance from different stakeholders to these various forms of switching.

Therefore, we believe that the clinical profession, academia and patients need to be involved in the policy framework for off-patent biologicals and biosimilars, see Box 1. Due to the complex nature of off-patent biologicals and biosimilars, it is clear that the appropriate use of these products needs to be a clinical decision made by a treating physician for an individual patient on the basis of shared decision-making with that patient [15]. The decision needs to balance the physician’s freedom to prescribe with his/her therapeutic and budgetary accountability based on scientific evidence, clinical experience and expert judgement. In order to make an informed and documented decision, physicians need to be supported by developing the evidence base around switching, including real-world data, pharmacovigilance data, switching data and outcome data [16]. Scientific and medical societies have a particular responsibility to provide detailed guidance on appropriate use through position statements [17]. Furthermore, the role of hospital pharmacists is important as they provide a ‘hub of information’ in respect of the uptake, good use and evidence base (monitoring of outcomes, real-world use and reporting of adverse events).

A number of European countries have implemented other physician incentives, such as quota [18]. From those experiences applied in countries with social health insurance systems clearly results that sufficient success will only be realized as far as a formal involvement of the medical profession and other relevant stakeholders is put in place.

In Europe, pharmacist substitution, i.e. the practice of a pharmacist dispensing a different, but similar biological medicine other than that which was prescribed, is a Member State responsibility. Today, the majority of European countries do not favour pharmacist substitution of a biosimilar for a reference biological medicine, although several countries are experimenting with various pharmacist substitution policies [18]. Pharmacist substitution should only be considered in well-defined circumstances, motivated by specific needs and informed by high quality evidence. If a country would consider pharmacist substitution, policymakers need to ensure that any substitution policies guarantee that the prescribing physician is aware of and approves which specific product is dispensed, that pharmacists are trained to provide unbiased information about off-patent biologicals and biosimilars, and that patients are fully informed and agree with substitution.

Gainsharing

A third building block that can align different supply- and demand-side stakeholders in promoting a competitive and sustainable market for off-patent biologicals and biosimilars relates to the recent trend of ‘gainsharing’, see Box 1. Several European countries are experimenting with gainsharing arrangements, which share the savings generated from off-patent biological and biosimilar competition between stakeholders, e.g. healthcare payers, hospitals, physicians and patients [19]. For instance, savings can be invested in supporting physicians and nurses when switching patients or in providing additional services to patients. Today, the experience with gainsharing arrangements is limited and future studies need to investigate the optimal design and impact of such arrangements.

In our opinion, policymakers need to introduce a long-term, sustainable and specific policy framework based on a multi-stakeholder approach with a view to fostering a fair, competitive and sustainable market for off-patent biologicals and biosimilars in Europe. Although there exists residual uncertainty regarding the appropriate terms for switching off-patent biologicals and biosimilars, we believe that such issues will be clarified and resolved over the coming years with the development of new studies, data and experience with these products. Additionally, we advocate that a policy framework for the off-patent biological and biosimilar market needs to be founded on multiple building blocks including the implementation of supply- and demand-side incentives, and the prospective evaluation of gainsharing arrangements.

Competition among off-patent biologicals and biosimilars in Europe benefits patients as it may help to control drug expenditure, expand access to health care, increase treatment choices, and encourage pharmaceutical innovation. However, there remains uncertainty about switching patients from a reference biological product to a biosimilar; from one biosimilar to another biosimilar; and about switching on multiple occasions. Therefore, we believe that the clinical profession, academia and patients need to be involved in developing a policy framework for off-patent biologicals and biosimilars. Due to the complex nature of off-patent biologicals and biosimilars, it is clear that the appropriate use of these products needs to be a clinical decision made by a treating physician for an individual patient on the basis of shared decision-making with that patient.

The authors would like to thank John Bowis, Laura Batchelor and Johan Van Calster from FIPRA for facilitating and chairing the roundtable discussions.

This work was enabled by Amgen, MSD and Pfizer.

Competing interests: SS is one of the founders of the KU Leuven Fund on Market Analysis of Biologics and Biosimilars following Loss of Exclusivity. SS has previously conducted biosimilar research sponsored by Hospira (now Pfizer Inc); and has participated in an advisory board meeting on biosimilars for Pfizer Inc. NB and AvB declare no competing interests. RW is currently principal investigator for Galapagos/Gilead and Celltrion; and has received unrestricted research grants to the KU Leuven from BMS, Janssen and Roche.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Professor Steven Simoens, PhD

KU Leuven, Faculteit Farmaceutische Wetenschappen

Department of Pharmaceutical and Pharmacological Sciences

Onderwijs en Navorsing 2, bus 521 49 Herestraat

BE-3000 Leuven, Belgium

Professor Claude Le Pen, PhD

Paris Dauphine University LEGOS Laboratory of Economics and Management of Health Organizations

Place du Maréchal de Lattre de Tassigny FR-75775 Paris Cedex 16, France

Niels Boone, PharmD

Orbis Medical Center

Department of Clinical Pharmacy and Toxicology

PO Box 5500

NL-6130 MB Sittard-Geleen, The Netherlands

Professor Ferdinand Breedveld, MD, PhD

Professor of Rheumatology

European League Against Rheumatism Leiden University Medical Center EULAR/EMA Liaison

83a Rapenburg

NL-2311 GK Leiden, The Netherlands

Antonella Celano, President

Italian National Association of People with Rheumatological and Rare Diseases 16 Via Molise

IT-73100 Lecce (LE), Italy

Antonio Llombart-Cussac, MD, PhD

Medica Scientia Innovation Research (MedSIR ARO)

Barcelona, Spain

Hospital Arnau de Vilanova de Valencia Valencia, Spain

Frank Jorgensen, MPharm, MM

The Hospital Pharmacy Bergen

NO-5085 Bergen, Norway

Andras Süle, PhD

Chief Pharmacist

Péterfy Hospital and Trauma Center 8-20 Peterfy Sandor u

HU-1076 Budapest, Hungary

Ad A van Bodegraven, MD, PhD Gastroenterologist

Department of Gastroenterology, Geriatrics, Internal and Intensive Care Medicine (COMIK)

Zuyderland Medical Centre

PO Box 5500

NL-6130 MB Sittard-Geleen, The Netherlands

Department Gastroenterology

Amsterdam University Medical Centres (AUMC), location Vrije Universiteit

1117 De Boelelaan

NL-1081 HV Amsterdam, The Netherlands

Professor Rene Westhovens, MD, PhD

Professor of Rheumatology

University Hospital Leuven – Rheumatology

49 Herestraat

BE-3000 Leuven, Belgium

Rijksinstituut voor ziekte- en invaliditeitsverzekering

Jo De Cock, Administrator-General 211 Tervurenlaan

BE-1150 Brussels, Belgium

References

1. European Medicines Agency. Guideline on similar biological medicinal products. 2014 [homepage on the Internet]. [cited 2018 Jul 13]. Available from: http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Scientific_guideline/2014/10/WC500176768.pdf

2. Madsen S. Improving access to modern therapies: what can we learn from gainsharing practices? The Scandinavian experience. 15th Biosimilar Medicines Conference. 23-24 March 2017, London, UK.

3. Bosco JLF, Bryant A, Dreyer NA. The current biosimilars landscape and methodological considerations for real-world evidence generation. Value Outcomes Spotlight. 2017;3:15-8.

4. QuintilesIMS. The impact of biosimilar competition in Europe. 2017 [homepage on the Internet]. [cited 2018 Jul 13]. Available from: http://www.medicinesforeurope.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/IMS-Biosimilar-2017_V9.pdf

5. European Commission. Joint report on health care and long-term care systems & fiscal sustainability: volume 1. Institutional paper 037. 2016 [homepage on the Internet]. [cited 2018 Jul 13]. Available from: https://publications.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/d6042a45-b535-11e6-9e3c-01aa75ed71a1/language-en

6. OECD. Tackling wasteful spending on health. Paris: OECD Publishing; 2017.

7. European Commission. Second multi-stakeholder workshop on biosimilar medicinal products. 20 June 2016 [homepage on the Internet]. [cited 2018 Jul 13]. Available from: http://ec.europa.eu/growth/content/second-multi-stakeholder-workshop-biosimilar-medicinal-products_en

8. European Commission. Third stakeholder conference on biosimilar medicines. 5 May 2017 [homepage on the Internet]. [cited 2018 Jul 13]. Available from: http://ec.europa.eu/growth/content/third-stakeholder-conference-biosimilar-medicines-0_is

9. Declerck P, Simoens S. A European perspective on the market accessibility of biosimilars. Biosimilars. 2012;2:33-40.