Author byline as per print journal: Adjunct Professor Valderilio Feijó Azevedo, MD, PhD, MBA; Associate Professor Brian Bressler, MD, MS, FRCPC; Madelaine A Feldman, MD, FACR; Professor Alejandro Mercedes, MD

| Abstract: As more biological medicines and biosimilars become increasingly available worldwide, clear product identification is critical for accurate pharmacovigilance. |

Submitted: 25 September 2017; Revised: 25 September 2017; Accepted: 27 September 2017; Published online first: 2 October 2017

When a patient experiences an adverse event from a medication or the medicine stops working, it is important for both the patient and their physician to know which medicine produced these effects. Yet, with a fairly new and effective class of medicines called biologicals, it is becoming more difficult for physicians worldwide to accurately track patient’s response and monitor potential problems. Luckily, the World Health Organization (WHO) – which assigns the scientific or ‘non-proprietary’ names for medicines – has developed a solution that will help physicians and regulators keep patients safe in whatever country they seek treatment.

Biological medicines – effective therapies grown in living cells – are used to treat patients suffering from serious conditions like rheumatoid arthritis, Crohn’s disease and cancer. Biosimilars are highly similar (but not exact) copies of these medicines and are becoming increasingly available worldwide. Biosimilars offer patients more treatment options at a lower healthcare cost. The complexity of biologicals and how they are produced in living cells mean that no two biologicals – whether originator or biosimilar – will ever be identical. This complexity can make these medications vulnerable to unintended properties that could result in adverse events or reduced efficacy. Clear product identification is particularly important with biologicals due to the risk of unwanted immune reactions in patients, and the sensitive and complex nature of these medicines.

For these reasons, WHO has proposed a modification to their naming system to ensure precise identification of biologicals. Biological naming is currently governed by a patchwork of policies that vary widely by country.

For example in Europe, five different biological medications manufactured by seven different companies, all sharing the non-proprietary name ‘filgrastim’ are currently being sold. While each is marketed by its trade name in Europe, many physicians around the world, including in Europe, prescribe using the non-proprietary name alone. This ambiguity leaves it unclear to the dispenser which biological medicine was intended, and unclear to the prescriber which was actually received by the patient. This makes it difficult to accurately assess which drug the patient is responding to or having a side effect from.

In addition, adverse events could be pooled or potentially misattributed to the wrong medication, making tracking the problem difficult. This leaves untraceable patients at risk for the adverse event. In Thailand, more than 15 biological medicines shared the same non-proprietary name. When a significant increase in adverse events occurred, the regulator could not easily determine which product (or products) was responsible.

Distinct naming, however, ensures accurate tracking to the exact medicine responsible, if any problems should arise. This also promotes greater manufacturer accountability for their products.

WHO, which assigns International Nonproprietary Names (INNs) to medicines, has proposed a solution that will make a uniform option available for national regulators to adopt. Their plan consists of a four-letter code called the Biological Qualifier (BQ), which will be attached to the INN name and will indicate where and by whom the biological was manufactured. When fully implemented, the BQ will extend the protections of distinct naming to patients worldwide, regardless of which country they seek treatment. This is especially helpful in the many countries without a robust pharmacovigilance system in place. For those countries which do, the BQ serves as an additional safeguard.

We commend WHO for their leadership in proposing a global solution to this problem, and await its availability for implementation. National regulatory authorities should follow suit and volunteer to be among the first to implement the WHO’s BQ proposal, bringing the many benefits of distinguishable biological naming to their patients.

Competing interests: This paper is funded by Alliance for Safe Biologic Medicines.

Adjunct Professor Valderílio Feijó Azevedo is a speaker for AbbVie, AstraZeneca, BMS, Celltrion, Janssen, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, Sanofi, UCB; and had produced graphic material to AbbVie, Janssen, BMS, Pfizer. He is also a member of the advisory board of AbbVie, AstraZeneca, BMS, Janssen, Merck Serono, Pfizer.

Associate Professor Brian Bressler is an advisor and speaker for AbbVie, Actavis, Ferring, Genentech, Janssen, Merck, Pfizer, Shire, Takeda. He is also an advisor for Allergan, Amgen, Celgene, Pendopharm. He provides research support for AbbVie, Alvine, Atlantic Pharmaceuticals, Amgen, BMS, Boehringer Ingelheim, Celgene, Genentech, GSK, Janssen, Merck, Qu Biologic, RedHill Biopharm, Takeda. He has stock options in Qu Biologic.

Dr Madelaine A Feldman teaches at the Department of Rheumatology at Tulane University Medical School, New Orleans, LA, USA. She is on a speaker bureau for Eli Lilly, and was on a speaker bureau for UCB.

Professor Alejandro Mercedes did not provide a conflict of interest statement.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; internally peer reviewed.

Adjunct Professor Valderilio Feijó Azevedo, MD, PhD, MBA

Professor of Rheumatology

Federal University of Paraná, 24 Rua Alvaro Alvin, Casa 18 Seminário, Curitiba-Paraná, PR-80740-260, Brazil

Associate Professor Brian Bressler, MD, MS, FRCPC

Founder, The IBD Centre of BC

Director, Advanced IBD Training Program

Clinical Associate Professor of Medicine

Division of Gastroenterology

University of British Columbia

770–1190 Hornby Street

Vancouver, BC V6Z 2K5

Canada

Madelaine A Feldman, MD, FACR

The Rheumatology Group, LLC

Suite 530, 2633 Napoleon Avenue

New Orleans, LA 70115

USA

Professor Alejandro Mercedes, MD

Professor of and Clinical Instructor in Clinical Oncology

Clinical Oncologist

Instituto Nacional del Cáncer Rosa Tavares (INCART)

Calle Correa y Cidró, Zona Universitaria Santo Domingo, Distrito Nacional

Dominican Republic

|

Author for correspondence: Madelaine A Feldman, MD, FACR, The Rheumatology Group, LLC, Suite 530, 2633 Napoleon Avenue, New Orleans, LA 70115, USA |

Disclosure of Conflict of Interest Statement is available upon request.

Copyright © 2018 Pro Pharma Communications International

Permission granted to reproduce for personal and non-commercial use only. All other reproduction, copy or reprinting of all or part of any ‘Content’ found on this website is strictly prohibited without the prior consent of the publisher. Contact the publisher to obtain permission before redistributing.

Source URL: https://gabi-journal.net/clear-naming-traceability-of-biological-medicines-will-protect-patients.html

Author byline as per print journal: Valderílio Feijó Azevedo1,2, Alejandra Babini3,4, Fabio Vieira Teixeira5,6, Igor Age Kos1,2, Pablo Matar7

|

Introduction: The Latin American Forum on Biosimilars (FLAB) is an annual meeting that brings together various stakeholders, including key opinion leaders, the pharmaceutical industry, academics, patients, lawyers and other healthcare professionals, to present and discuss recent findings regarding biosimilars. In 2015, the meeting theme was interchangeability and automatic substitution. Regarding biosimilarity, interchangeability and extrapolation of indications, the discussion centred on two products in Brazil and Argentina: CT-P13, an infliximab biosimilar; and RTXM83, a rituximab biosimilar. Here, we conduct a critical analysis of the available scientific and medical information on these products to establish a FLAB position statement in the context of the current regulations in Brazil and Argentina. |

Submitted: 15 March 2016; Revised: 30 May 2016; Accepted: 31 May 2016; Published online first: 13 June 2016

The annual Latin American Forum on Biosimilars (FLAB) was first held in 2010 with the aim of bringing key stakeholders within the community together to discuss aspects of biosimilars. Attended by key opinion leaders, representatives from the pharmaceutical industry, academics, patients, lawyers and healthcare professionals, FLAB is sponsored or supported by different organizations, including the pharmaceutical industry such as AbbVie, Janssen, Pfizer, Sandoz, Sanofi; patient organizations and Latin American medical societies such as Brazilian Society of Rheumatology, Argentinian Society of Rheumatology, GEDIB (Brazilian Study Group of Inflammatory Bowel Diseases) among others; some regulatory agencies such as ANVISA (Agencia Nacional de Vigilancia Sanitaria), COFEPRIS (Comisión Federal para la Protección contra Riesgos Sanitarios), ANAMED (Agencia Nacional de Medicamentos), have sent representatives to the Forum in order to discuss regulatory aspects of biosimilars approved in their countries. The 2015 meeting was held in Brasília, Brazil, with the theme of ‘Interchangeability and Automatic Substitution’, and saw the approval of two potential biosimilars in different Latin American countries.

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines similar biotherapeutic products (SBPs) as products that are similar in terms of quality, safety and efficacy to an already-licensed reference biotherapeutic product (RBP) [1]. An SBP is tested for biosimilarity via a biosimilarity exercise in which it is compared with existing products using the same procedures. Within this biosimilarity exercise, there are three levels of evaluation: quality evaluation (i.e. physicochemical and biological characterization), non-clinical evaluation and clinical evaluation. Clinical evaluation seeks to demonstrate the comparable safety and efficacy of the SBP with the RBP. It is a stepwise procedure that begins with pharmacokinetic (PK) and pharmacodynamic (PD) studies, followed by efficacy and safety clinical trial(s). Given that biotherapeutic products are biologically active molecules capable of inducing immune responses, immunogenicity is an important consideration within the evaluation of safety. In our opinion, all biological products supported by a full biosimilarity exercise can be considered true biosimilars. Conversely, products that are not fully supported by scientific information, including comparative clinical data, cannot be considered biosimilars.

In Europe, a similar definition has been established that states: ‘biosimilars are copy biologicals with a clear and effective regulatory route for approval, which allows marketing of safe and efficacious biological products’ [2]. This conceptual idea has been well established by the European Medicines Agency’s (EMA) guidelines [3], which have led to the approval of several biosimilars in Europe, including the first biosimilar monoclonal antibody (mAb), the anti-tumour necrosis factor (anti-TNF) drug infliximab. In September 2013, the Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) of EMA, approved the use of biosimilar of Remicade™ under the trade names of Remsima™ and Inflectra™ [4, 5].

Other biosimilar mAbs and fusion proteins that are currently being investigated include: rituximab, which is in the early stages of clinical trials; and adalimumab and etanercept, which are in phase III clinical trials.

The main objective of this paper is to provide a critical analysis of the results of the biosimilarity exercises carried out on two products that have been recently approved in Brazil and Argentina: CT-P13, an infliximab biosimilar; and RTXM83, a proposed rituximab biosimilar. As a result, we have established a FLAB position statement on the approval of these drugs in the context of the current regulations in Brazil and Argentina.

At present, a number of countries in Latin America have specific regulations concerning the approval of SBPs (Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Costa Rica, Cuba, Guatemala, Mexico, Panama, Peru and Venezuela). In general, regulations consider the international standards set out by EMA, in combination with local input and scientific principles based on WHO guidelines. Most legislation for biosimilar approval considers it essential to implement a system of pharmacovigilance after product commercialization, to ensure that the safety and efficacy of biosimilars can be evaluated [6].

In Argentina, resolutions outlining the requirements for biopharmaceuticals and biosimilar products (No. 7075 [7] and 7729 [8]) were published in 2011 by the ANMAT. Resolution No. 7729 specifically states the requirements for the approval of biosimilars. Of note, Article 6 states that the comparative exercise between the reference product and proposed biosimilar must be accompanied by non-clinical and clinical studies in order to be approved. In 2012, ANMAT enacted Resolution No. 3397, which established the requirements for the approval of biological medicines obtained using DNA recombinant technology, including mAbs [9].

In 2013, the Brazil-based pharmaceutical company, Libbs, and the Chemo Group’s biotechnology company, mAbxience, signed a licensing and technology transfer agreement for several biosimilar mAbs developed by mAbxience, including the rituximab biosimilar. A clinical trial sponsored by mAbxience entitled: ‘A Randomized, Double-blind, Phase III Study Comparing Biosimilar Rituximab (RTXM83) Plus CHOP Chemotherapy Versus a Reference Rituximab Plus CHOP (R-CHOP) in Patients With Diffuse Large B-cell Lymphoma (DLBCL) Given as First Line’ was registered under the ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT02268045 on 19 September 2014. Libbs and Elea, an Argentina-based company, are among the collaborators that worked towards establishing this protocol. This study is a non-inferiority trial and is currently recruiting participants. Despite this, in Argentina, ANMAT enacted Regulation No. 7060 (dated 2 October 2014), which authorized the commercialization of the biopharmaceutical product Novex (sponsored by Elea), that contains the rituximab biosimilar, RTXM83 [10]. As clinical trials are ongoing, it is evident that this was approved by ANMAT without any clinical data which is contrary to legislation [7–9].

Novex is now being distributed in hospitals and health centres in Argentina to be administered to patients diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis (RA). As this product has been approved without clinical data, the Argentine Society of Rheumatology has issued a statement suggesting their associates do not administer Novex to patients.

In contrast, a very different situation exists in Brazil. The infliximab biosimilar, CT-P13 (Remsima™), sponsored by Celltrion, received market approval by ANVISA in 29 April 2016. This approval was based on full clinical development, including a phase I clinical trial, known as the PLANETAS trial [11], which compared treatment with CT-P13 to innovator infliximab in individuals with active ankylosing spondylitis. The outcomes, pharmacokinetics and clinical efficacy, including the Assessment in Ankylosing Spondylitis Response Criteria (ASAS) 20 and ASAS 40 responses, were similar in both treatment groups; and the product safety profiles were also comparable up to week 30. After this, a phase III clinical trial, known as the PLANETRA trial [12], was performed, which compared CT-P13 to innovator infliximab in patients with active RA who did not respond well to methotrexate treatment. Equivalence was demonstrated in the American College of Rheumatology 20% (ACR 20) response at week 30. Currently, several trials with proposed biosimilars are in progress and it seems highly likely that approval and marketing of new products will be requested in the near future [13].

Evidence suggests that, although the infliximab biosimilar, CT-P13, was approved in Brazil following full development that demonstrated clinical biosimilarity, interchangeability with the infliximab innovator is not guaranteed. Biosimilars cannot be considered interchangeable or a substitute for their reference product based solely on biosimilarity evidence. It should be left to the clinician’s judgement to choose whether to switch from an originator to a biosimilar. Other paramedical individuals and healthcare payers should not be allowed to change prescriptions or impose the use of biosimilars instead of their originator. Biosimilars should be considered interchangeable if the manufacturer has demonstrated that the drug can produce similar effects to the reference product in any given patient. Moreover, Brazilian medical societies point out that when a biological product is administered to an individual more than once, the risk, in terms of safety or diminished efficacy, of alternating between using the biosimilars and the reference product, is not greater than the risk of using the reference product without such alteration or switch [12]. The best approach should be to conduct a rigorous clinical study to evaluate the possibility of the reference and biosimilar being interchangeable.

The NOR-SWITCH trial (NCT02148640) [14] is a prospective randomized study that aims to examine the ease with which CT-P13 can be interchanged with the infliximab innovator. The authors plan to recruit 500 patients with five different indications for infliximab: RA, plaque psoriasis, ankylosing spondylitis (AS), Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC). All patients will be treated with the infliximab innovator for six months. After this time, half will switch to treatment with CT-P13 and the other half will remain on the infliximab innovator. After 52 weeks, clinical observations will be made by physicians and patients to determine the efficacy of the switch. It is hoped that this will provide robust evidence in support of switching from the reference product to the biosimilar. However, it is generally accepted that clinical trials to assess interchangeability should have crossover or Balaam’s design [15], neither of which are incorporated in this trial; therefore, it cannot be considered an appropriate interchangeability study. No biosimilar should be considered interchangeable until proven by clinical medical evidence [16].

An example of such an interchangeability trial was recently carried out in Italy. Data from the Prospective Observational Cohort Study on patients with inflammatory bowel disease receiving Therapy with BIOsimilars (PROSIT-BIO), obtained from patients with UC and CD, was presented at the Italian Group for the Study of Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IG-IBD), VII National Congress in Palermo [17]. With 397 patients (174 UC and 223 CD), this is the largest interchangeability study carried out to date. It demonstrated that comparable efficacy was observed in patients who were switched from the infliximab innovator to the infliximab biosimilar (93 patients), compared to patients receiving a biosimilar who had previously been naïve to anti-TNF (217 patients), and patients receiving a biosimilar who had previously been exposed to one or more biologicals (87 patients) (response rate 95% vs 92% vs 91%, respectively). Safety was also found to be comparable across the patient groups.

Extrapolation of indications is a regulatory decision. CT-P13 is an example of this because it was extrapolated in more than 50 countries including Brazil. This decision is controversial because the biosimilarity of CT-P13 was tested in only two disease models, RA and AS, and then extrapolated to inflammatory bowel disease. The Brazilian regulation of biosimilars, such as RDC 55/2010, has two pathways: individual and comparability. When a biosimilar is only submitted to the individual pathway, it is not possible to extrapolate indications. Submissions must also be made to the comparability pathway in order to enable the extrapolation of indications.

Conversely, Argentinian regulation of biosimilars does not permit extrapolation of indications. The case of the rituximab biosimilar RTXM83, which was approved in Argentina, is challenging. To the best of our knowledge, this product has been approved for all the indications of the rituximab innovator without any clinical data. Therefore, this product is not a true biosimilar because biosimilarity, with respect to the reference product, has not been fully demonstrated.

Based on the evidence, CT-P13 is the only monoclonal antibody marketed in Latin America that can be considered a true biosimilar. Extrapolation is only acceptable when the diseases for which the reference product is used to treat are entirely similar. Extrapolation based on only preclinical studies is unacceptable. Currently, there is no clinical evidence to support that CT-P13 and the reference product are interchangeable.

Conversely, although the proposed rituximab biosimilar (RTXM83) was approved by ANMAT in Argentina, clinical data demonstrating its equivalence with the reference rituximab is necessary before RTXM83 can be considered a true biosimilar.

The interest in biosimilars is growing in Latin America due to a number of factors, including the large proportion of healthcare resources that are used to import high cost branded biologicals. Biosimilars are expected to reduce drug expenditure, assuming that they achieve similar clinical results as the reference product. The need for well-defined pathways and regulations for the review, approval and pharmacovigilance of biosimilars, as well as greater transparency of the actions of governments, are required to facilitate appropriate biosimilar approval and usage. As both Brazil and Argentina have specific regulations concerning the approval of biosimilars, their governments are responsible for guaranteeing the approval of safe and effective biosimilar products.

Disclosure of financial support: The authors declare they have not received any financial incentive to write this paper. This work was not produced with any financial support.

Visit the link www.biossimilares2016.com.br for further information on FLAB.

Competing interests: Adjunct Professor Valderílio Feijó Azevedo is a speaker for AbbVie, AstraZeneca, BMS, Celltrion, Janssen, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, Sanofi, UCB; and has produced graphic material to AbbVie, Janssen, BMS, Pfizer. He is also a member of the advisory board of AbbVie, AstraZeneca, BMS, Janssen, Merck Serono, Pfizer. Alejandra Babini declares that she is President of the Argentinian Rheumatology Society. She is a consultant, speaker and member of the advisory board of AbbVie and Pfizer. Fabio Vieira Teixeira declares that he is a consultant, speaker and a member of the advisory board of Janssen and Hospira/Pfizer. He is also a consultant and speaker of Ferring and Nestlé. Igor Age Kos and Pablo Matar declare no relevant conflict of interests to participate in this authorship.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Adjunct Professor Valderílio Feijó Azevedo1,2, MD, PhD, MBA

Alejandra Babini3,4

Professor Fabio Vieira Teixeira5,6, MSc, MD, PhD

Igor Age Kos1,2

Pablo Matar7

1Federal University of Paraná, Rua Alvaro Alvin, Casa 18 Seminário, Curitiba-Paraná PR 80740–080, Brazil

2Edumed-Health Research and Biotech, 2495 Avenue Bispo Dom José, Seminário

Curitiba-Paraná, Brazil CEP 80440080

3Hospital Italiano Córdoba – Argentina

4Argentinian Society of Rheumatology, Callao 384 Piso 2 Dto 6, CABA, Buenos Aires, Argentina (C1022AAQ)

5Medical Director of Gastrosaude Clinic-Marilia, 62 Sao Paulo Avenue, 17509-190 Marilia, Sao Paulo, Brazil

6Brazilian Study Group on Bowel Inflammatory Diseases

7CONICET – The Argentinian Scientific andTechnical Research Council, Centro Científico Tecnológico Rosario – CONICET

Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas, Ocampo y Esmeralda, Rosario 2000 – Santa Fe, Argentina

References

1. World Health Organization. Guidelines on evaluation of similar biotherapeutic products (SBPs). 2009 [homepage on the Internet]. [cited 2016 May 30]. Available from: http://www.who.int/biologicals/areas/biological_therapeutics/BIOTHERAPEUTICS_FOR_WEB_22 APRIL2010.pdf

2. Thorpe R, Wadhwa M. Terminology for biosimilars – a confusing minefield. Generics and Biosimilars Initiative Journal (GaBI Journal). 2012; 1(3-4):132-4. doi:10.5639/gabij.2012.0103-4.023

3. European Medicines Agency. Committee for Medical Products for Human Use (CHMP). Guideline on similar biological medicinal products. 30 October 2005 [homepage on the Internet]. [cited 2016 May 30]. Available from: http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Scientific_guideline/2009/09/WC500003517.pdf

4. European Medicines Agency. Assessment report Inflectra. EMA/CHMP/589422/2013. 27 June 2013 [homepage on the Internet]. [cited 2016 May 30]. Available from: http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en GB/document library/EPAR – Public assessment report/human/002778/WC500151490

5. European Medicines Agency. Assessment report Remsina. EMA/CHMP/589317/2013. 27 June 2013 [homepage on the Internet]. [cited 2016 May 30]. Available from: http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en GB/document library/EPAR – Public assessment report/human/002576/WC500151486.pdf

6. Azevedo VF, Mysler E, álvarez AA, Hughes J, Flores-Murrieta FJ, Ruiz de Castilla EMR. Recommendations for the regulation of biosimilars and their implementation in Latin America. Generics and Biosimilars Initiative Journal (GaBI Journal). 2014;3:143-8. doi:10.5639/gabij.2014.0303.032

7. Ministerio de Salud Secretaria de Politicas, Regulacion e Institutos A.N.M.A.T. Disposicion n 7075. 14 October 2011 [homepage on the Internet]. [cited 2016 May 30]. Available from: http://www.anmat.gov.ar/boletin_anmat/octubre_2011/Dispo_7075-11.pdf

8. Ministerio de Salud Secretaria de Politicas, Regulacion e Institutos A.N.M.A.T. Disposicion n 7729. 14 November 2011 [homepage on the Internet]. [cited 2016 May 30]. Available from: http://www.anmat.gov.ar/webanmat/retiros/noviembre/disposicion_7729-2011.pdf

9. Ministerio de Salud Secretaria de Politicas, Regulacion e Institutos A.N.M.A.T. Disposicion n 3397. 12 June 2012 [homepage on the Internet]. [cited 2016 May 30]. Available from: http://www.anmat.gov.ar/webanmat/Legislacion/Medicamentos/Disposicion_3397-2012.pdf

10. Ministerio de Salud Secretaria de Politicas, Regulacion e Institutos A.N.M.A.T. Disposicion n 7060. 2 October 2014 [homepage on the Internet]. [cited 2016 May 30]. http://www.anmat.gov.ar/boletin_anmat/Octubre_2014/Dispo_7060-14.pdf

11. Park W, Hrycaj P, Jeka S, Kovalenko V, Lysenko G, Miranda P, et al. A randomised, double-blind, multicentre, parallel-group, prospective study comparing the pharmacokinetics, safety, and efficacy of CT-P13 and innovator infliximab in patients with ankylosing spondylitis: the PLANETAS study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72(10):1605-12.

12. Yoo DH, Hrycaj P, Miranda P, Ramiterre E, Piotrowski M, Shevchuk S, et al. A randomised, double-blind, parallel-group study to demonstrate equivalence in efficacy and safety of CT-P13 compared with innovator infliximab when coadministered with methotrexate in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis: the PLANETRA study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72(10):1613-20.

13. Azevedo VF, Meirelles Ede S, Kochen Jde A, Medeiros AC, Miszputen SJ, Teixeira FV, et al. Recommendations on the use of biosimilars by the Brazilian Society of Rheumatology, Brazilian Society of Dermatology, Brazilian Federation of Gastroenterology and Brazilian Study Group on Inflammatory Bowel Disease-Focus on clinical evaluation of monoclonal antibodies and fusion proteins used in the treatment of autoimmune diseases. Autoimmun Rev. 2015;14(9):769-73. doi:10.1016/j.autrev.2015.04.014. Epub 2015 May 1.

14. ClinicalTrials.gov. The NOR-SWITCH Study (NOR-SWITCH) [homepage on the Internet]. [cited 2016 May 30]. Available from: http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02148640

15. Chow SC. Biosimilars: design and analysis of follow-on biologics. Chapman and Hall; 2013. Page 19.

16. Fiorino G, Girolomoni G, Lapadula G, Orlando A, Danese S, Olivieri I; SIR, SIDeMaST, and IG-IBD. The use of biosimilars in immune-mediated disease: a joint Italian Society of Rheumatology (SIR), Italian Society of Dermatology (SIDeMaST), and Italian Group of Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IG-IBD) position paper. Autoimmun Rev. 2014 Jul;13(7):751-5. doi:10.1016/j.autrev.2014.02.004. Epub 2014 Mar 19.

17. Fiorino G, et al. 439 The PROSIT-BIO cohort of the IG-IBD: a prospective observational study of patients with inflammatory bowel disease treated with infliximab biosimilars. Gastroenterology. 2016;150(4):S92.

|

Author for correspondence: Adjunct Professor Valderilio Feijó Azevedo, MD, PhD, MBA, Rua Alvaro Alvim 224 casa 18, Seminário, Curitiba-Paraná CEP 80440–080, Brazil |

Disclosure of Conflict of Interest Statement is available upon request.

Copyright © 2016 Pro Pharma Communications International

Permission granted to reproduce for personal and non-commercial use only. All other reproduction, copy or reprinting of all or part of any ‘Content’ found on this website is strictly prohibited without the prior consent of the publisher. Contact the publisher to obtain permission before redistributing.

Source URL: https://gabi-journal.net/new-monoclonal-antibody-biosimilars-approved-in-2015-in-latin-america-position-statement-of-the-latin-american-forum-on-biosimilars-on-biosimilarity-interchangeability-and-extrapolation-of-indications.html

|

Study objectives: In Latin America, many governments have attempted to address biosimilar safety and efficacy concerns by developing abbreviated regulatory pathways to increase access while controlling quality. This study explores discount and evidence requirements for payers and physicians to provide access to and prescribe biosimilars in Argentina, Brazil and Mexico. |

Submitted: 24 November 2014; Revised: 5 February 2015; Accepted: 9 February 2015; Published online first: 20 February 2015

As with generic small-molecule medicines, the potential for cost savings resulting from the use of biosimilars is attractive to payers worldwide [1, 2]. This attraction has increased sharply in recent years as the impact of biological drugs on health plan budgets has exploded. In Brazil, for example, biotherapeutic products represented 2% of medicines prescribed, yet accounted for 41% of the annual Ministry of Health pharmaceutical budget in 2010 [3]. Biosimilars, however, are different than small molecule generics due to the inherent variability in the production process for biopharmaceutical products and the relatively limited experience that stakeholders have with them. Physicians in particular raise concerns about the degree to which this variability in production may result in differing levels of safety and efficacy of biosimilars relative to their branded equivalents – and each other. Fear of potential immunogenicity issues arising from differences in the biological production process is a concern with biosimilars, and is associated with the need for post-launch pharmacovigilance programmes as seen in Europe. This complex production process is considerably more expensive than that of small molecules, adding to the costs of biosimilars. These factors, along with the matching of prices of biosimilars by originator companies, have resulted in a tempering effect on the launch and uptake of biosimilars as regulators seek to ensure the bioequivalence of biosimilar products through head-to-head demonstration of biosimilarity to their branded originator products.

In Latin America, many governments have attempted to address these concerns by developing abbreviated regulatory pathways for biosimilars in order to increase access while controlling quality [4]. In previous work, we explored the regulatory approaches underway in some of the largest markets in the region [5]. This study builds on that work by exploring the evidence that payers from the selected countries in the region will require to provide access to biosimilars, as well as the price, market access and utilization potential for products that meet these evidence requirements.

We first conducted online searches, using Google and PubMed, in English, Portuguese and Spanish to update our understanding of the regulatory policies that exist in each of the three target countries: Argentina, Brazil and Mexico. These countries were chosen due to their populations and purchasing power (in terms of gross domestic product per capita) as representative of the most advanced pharmaceutical markets in the Latin American region. Sources included official government websites from each country and key legislation documentation such as Boletín Oficial (Argentina), Diário Oficial da União (Brazil), and Diario Oficial (Mexico). To build on our findings from the literature review, we then conducted exploratory interviews with payers and physician key opinion leaders (KOLs) in each country. Respondents were selected based on referrals from regional industry experts (payers) and PubMed searches (KOLs), and were offered honoraria ranging from US$250 to US$400 for their participation. We are not aware of any potential conflicts of interest among the respondents. Payer informants consisted of two benefits directors in Argentina, one each from a provincial social insurer and a private insurance plan respectively, two advisors to the National Commission for Incorporation of Technologies in SUS (Comissão Nacional de Incorporação de Tecnologias no SUS, CONITEC) and the Ministry of Health in Brazil, and two officials in Mexico, one each from a social insurer and the Ministry of Health respectively. Twenty-five KOLs were emailed an invitation to participate in the research, of which two declined the offer to participate. Physicians interviewed included four KOLs across the three countries, split across two specialties with high levels of biological drug use: haematologist oncologists (two interviews) and rheumatologists (two interviews).

For each of these interviews, we asked a structured set of questions designed to understand what evidence and discount levels payers and physicians will look for when making decisions about providing access to or prescribing biosimilar drugs. Areas of focus included expected impact drivers for the adoption of biosimilars, expected evidence requirements for public access and utilization, payer comfort in providing access versus expected cost savings, and expected discount requirements for access and prescribing. For expected impact drivers, payers and KOLs were asked to rank a list of potential factors in their order of importance in promoting the adoption of biosimilars, where 1 was the least important factor and 7 was the most important factor. For expected evidence requirements for public access and utilization, answers were compiled by collating responses to separate directed question on the topic during interviews into a spreadsheet for subsequent thematic analysis. For payer comfort in providing access versus expected cost savings, payers were asked to specify the opportunity a biosimilar would provide for cost savings to their organization and patients where 1 was no cost savings and 7 was high cost savings. This was repeated for a list of molecules. Then, for each molecule, payers were asked to specify for their level of comfort in promoting the adoption of biosimilars within their organizations where 1 was not at all comfortable and 7 was ‘extremely comfortable’.

Questions focused on a set of drug classes selected as having high potential for the entry of biosimilar products based on secondary research conducted on biosimilar products in development for European, Latin American and the US markets due to the high level of budget impact of the branded biological equivalents of the molecules in these classes. The classes include tumour necrosis factor inhibitors (anti-TNFs), granulocyte colony-stimulating factors (G-CSFs), erythropoiesis-stimulating agents (ESAs) and monoclonal antibodies used in oncology indications (cancer mAbs). Interviews were conducted in Portuguese and Spanish.

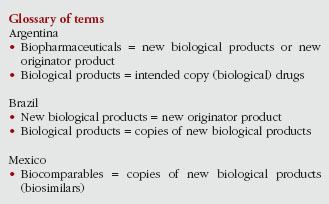

Throughout, we have used the term ‘biosimilars’ as the most common usage in the English language literature. However, other terms were noted during our research. For example, biosimilars are frequently referred to as ‘biological products’ in Brazil, as differentiated from ‘new biologicals’ to refer to a new branded agent, ‘biocomparables’ in Mexico, or medicamentos biológicos similares in Argentina.

While biosimilars offer the potential for significant cost savings, safety and quality concerns vary by country, stakeholder segment and therapy area based on a diverse range of factors including regulations, experience with biosimilars and the funding or financial resources of the payer or patient segment in consideration. Findings are summarized below by topic to offer insight into the differences that may exist across the countries included in the research.

Expected impact drivers for the adoption of biosimilars

When considering the attributes of potential therapies that would most impact their decision to adopt biosimilars, payers focus primarily on the total budget impact of the originator product, as well as the clinical value of the product per the evaluation of trusted physician expert advisors. Figure 1 shows the rating of impact drivers in the decision to adopt biosimilars by payers and physicians. This varies somewhat by country, with Brazilian payers placing the highest emphasis on total budget size, perhaps due to the centralized nature of the Brazilian national public healthcare system, the Sistema Único de Saude (SUS). More decentralized markets such as Argentina place a higher emphasis on the level of physician acceptance of the products than on budget impact, particularly in the short-term while clinical value is being proven. Across countries, concern for safety is expressed, particularly in regards to the potential for allergic reactions, but this is not expected to impede adoption as long as safety profiles are considered sufficiently acceptable to gain market approval by regulators. However, payers express skepticism that pharmacovigilance for biosimilars will be as stringent as with innovative biologicals. This theme is more pronounced in Argentina and Mexico than in Brazil, where payers show more concern about providing access to more complex biosimilar molecules such as monoclonal antibodies for more severe conditions. This could potentially reflect the significant budget impact that biological drugs are having on the SUS budget and payers’ increasing interest in biosimilars as a means to provide budgetary relief across disease states. While not one of the top drivers, payers across markets see breadth of indications as an important driver of overall biosimilar adoption. Disease treatment duration (acute versus chronic) and route of administration (intravenous versus subcutaneous) are considered less important factors for payer adoption of biosimilar products across markets.

KOLs across markets consistently rate clinical value as the most impactful product attribute to drive the adoption of biosimilar products. Total budget size is seen as having only moderate impact in Brazil, while KOLs in Argentina and Mexico rate budget considerations even higher than their payer countrymen, as they see economic arguments as the principal reason for considering the use of biosimilars, instead of their more established branded originators. Disease complexity is seen as a more important consideration with KOLs than payers in Brazil and Mexico, with KOLs expressing higher levels of concern for the use of more complex molecules in patients with life-threatening conditions, like cancer. Patients with severe and aggressive diseases may not survive long enough to try a different agent if a biosimilar fails to provide the same efficacy benefits, or introduces additional adverse events, compared with the originator molecule. Thus, KOLs are reluctant to use a biosimilar as they perceive that even minor differences in efficacy or safety could have major impacts on treatment outcomes and patient survival. This difference is particularly notable in Brazil, where KOLs worry about the high degree of receptivity to biosimilars that they perceive exists within the SUS. Disease treatment duration (acute versus chronic) and route of administration (intravenous versus subcutaneous) are also considered less important considerations for biosimilar adoption by KOLs, although Argentinian and Mexican KOLs note a moderate level of impact of route of administration due to the increasing preference among rheumatologists and patients for subcutaneous formulations to enable application in the doctor’s office instead of in the infusion clinic. KOLs also state that the number of approved indications does not impact their decision-making, which contrasts with payers, whose primary desire is to ensure that a new biosimilar has the same approved indication as the originator product before permitting access.

Expected evidence requirements for public access and utilization

Payers and KOLs consistently report that they will require comparative phase I, II and III trials before providing access to and prescribing biosimilar products, as shown in Table 1, which lists expected evidence requirements to provide public access to and prescribe biosimilar products. This represents a somewhat different viewpoint than those expressed by regulatory experts in previous interviews, who cited the potential for less stringent requirements for less complex molecules such as pegylated interferon and low molecular weight heparin via abbreviated regulatory pathways under development for biosimilars in some countries [4]. Indeed, under the ‘desenvolvimento individual’, or ‘individual development’, pathway in Brazil, ‘non-clinical and clinical studies can be reduced, depending on the amount of knowledge of pharmacological properties, safety and efficacy of the originator product [3]. Thus, Brazil has two regulatory pathways for biosimilars: a more rigorous path for more complex molecules, and a streamlined path for less complex molecules [4]. Payers and KOLs alike state that they will require non-inferior or better bioequivalence in clinical trials to demonstrate that biosimilars have similar efficacy and safety to their branded biological reference molecules. Meanwhile, payers across countries express that they will trust products approved via their countries’ regulatory processes are as safe and effective as their branded equivalents for the indications for which the biosimilars are approved. Similarly, payers state that they will defer the question of indication extrapolation to regulators and reimburse only approved indications, at least in the short-term as patients and clinicians (and payers themselves) gain experience with biosimilars. KOLs are more neutral and state a desire to reserve their opinion on the safety and efficacy of a given biosimilar until they have gained clinical experience with the product.

Payer comfort in providing access versus expected cost savings

Mexican payers stated a relatively low level of comfort permitting access to future biosimilars. This is shown in Figure 2, which depicts payer perceptions of cost savings and comfort providing access to select biosimilars across the drug classes of focus. The payer from the social insurer further clarified that this was due to his perception that, although the Norma enacted by the Mexican Government in September 2012 included regulations pertaining to Good Manufacturing Practices compliance, technical and scientific demonstrating safety, efficacy and quality, and requirements for biocomparability studies and pharmacovigilance of biosimilars [6], specific regulations had not yet been put in place to assess new biosimilar products for bioequivalence. Instead, products were registered and authorized as innovative biotech drugs, although payers cite examples of less complex biosimilars, such as interferon and erythropoietin, that were approved with only comparative data versus their branded reference biological drugs before the Norma was enacted. While payers state that to their knowledge no serious adverse events have been reported, they perceived uncertainty regarding the timing of implementation of bioequivalence assessments in future registration reviews has contributed to the relatively low level of comfort with biosimilars reported by Mexican payers. Furthermore, as a result of examples of more complex biosimilars being approved as innovative biologicals, some biosimilars have launched at prices similar to their branded equivalents, prompting the Mexican payers interviewed to report lower expected cost savings for biosimilars than in the other Latin American markets studied.

Brazilian payers’ concerns regarding biosimilars are also related to questions regarding assessment processes for regulatory approval. In particular, these payers note concern for products approved via the ‘individual development’ pathway, given the potential to gain approval with less rigorous standards than the ‘comparability’ pathway. Despite these safety concerns, Brazilian payers ultimately state that they will trust the registration decisions made by the Brazilian healthcare regulatory body ANVISA (Agência Nacional de Vigilância Sanitária), and as a result report a moderate level of comfort providing access to biosimilars, with particular interest in high-spend areas like rheumatology, haematology and oncology that have been particularly affected by increases in biological spending in recent years. Given the complexity of biosimilar production, however, payers are also tempered in their price expectations, reporting more moderate levels of anticipated cost savings versus brands than seen with small molecule generics. They note, however, that even relatively modest price discounts would result in significant overall budget impact given the significant biological volume in these drug classes.

Argentinian payers report a higher level of comfort providing access to biosimilars than their Brazilian and Mexican counterparts. This is driven by a higher level of confidence in ANMAT (Administración Nacional de Medicamentos, Alimentos y Tecnología Médica), the Argentinian healthcare regulatory agency, to rigorously assess biosimilar registration applicants for sufficient evidence demonstrating bioequivalent efficacy and safety. This holds for less complex biosimilars as well, as unlike in Brazil, Argentinian payers do not believe that abbreviated regulatory requirements would apply to less complex biosimilar molecules. As for price, Argentinian payers cite higher expected cost savings than their Brazilian and Mexican counterparts due to their belief that lower prices are the primary advantage that biosimilars can offer versus brands. Thus, without substantial cost savings there will be no rationale to justify biosimilar use.

Expected discount requirements for access and prescribing

For biosimilars that meet the evidence requirements discussed earlier and that gain regulatory approval, Brazilian payers report that a 15–30% discount below the price of the branded originator would be necessary for them to provide access to the biosimilar along with the brand, as shown in Figure 3. Since SUS purchases are made at the molecule level, usually to the lowest bidder, the discount levels to win SUS tender contracts could potentially be even lower in the future as biosimilars gain more experience in the market and competitive forces drive the originator price down. However, as the naming system for biosimilar mAbs has not yet been well defined by ANVISA, it is unclear if clinicians will be able to specify originators over biosimilars for SUS patients as they can in the private market. Based on their experience with the private market, payers believe discounts greater than 35% below the branded originator could start to prompt private payers to require patients to first try a biosimilar before reimbursing use of its branded equivalent, or requiring the patient to pay the difference in cost between the biosimilar and branded biological to use the brand first.

Argentinian payers respond similarly, citing a 10–20% discount below the branded price to provide access to the biosimilar as well as the brand. At discounts greater than 20% they report that they would attempt to restrict access to the brand by asking physicians in their networks to prescribe by molecule name without mentioning the brand or by excluding the original brands from pharmaceutical supply agreements if brand prices and payment terms varied significantly from those for their biosimilar counterparts.

In Mexico, because the healthcare regulatory body COFEPRIS (Comisión Federal para la Protección contra Riesgos Sanitarios, Federal Commission for the Protection against Sanitary Risks) registers biosimilars under the same product codes as their reference brands, social insurers like the Mexican Institute of Social Security (Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social, IMSS) and the State Employees’ Social Security and Social Services Institute (Instituto de Seguridad y Servicios Sociales de los Trabajadores del Estado, ISSSTE) cannot differentiate between them. As a result, biosimilars compete on equal footing as their reference brands at these public institutions via reverse auction tenders – tender offerings awarded to the manufacturer offering the lowest price determined by a downward-moving auction format – which usually result in discounts of as little as 5% being sufficient to purchase one biological product over another.

Across countries, KOLs cite a strong preference to prescribe branded biologicals over biosimilars due to their proven track records over years of study and market experience. However, KOLs across countries consistently acknowledge that payer access restrictions or patient affordability limitations could cause them to prescribe biosimilars instead of brands at discounts lower than 20–25%. Once the safety and efficacy of a given biosimilar is proven in the market, KOLs state that they likely will consider biosimilars for all patients at discount levels greater than 20-25%.

When asked what attributes of potential therapies would most impact their decision to adopt biosimilars, the small sample of Latin American payers from the markets included in our research focused primarily on the total budget impact of the branded equivalent of the product, as well as the clinical value of the product from respected clinical advisors. Similarly, Latin American KOLs across the selected countries consistently rated clinical value as the most impactful product attribute to drive the adoption of biosimilar products, and saw budgetary concerns as a secondary but still important consideration. Indeed, KOLs in Argentina and Mexico rated budget considerations even higher than their payer countrymen, as they saw economic considerations as the only rationale for considering the use of biosimilars instead of their more established branded equivalents.

While all respondents reported that they will require the full range of comparative trials before accepting biosimilar products, payers across markets consistently stated that they will defer to the regulatory authorities in their respective markets to determine whether biosimilars are safe and effective, and therefore felt comfortable providing access for approved indications. Payers expressed hesitation to provide access for extrapolated indications that have not been granted approval by the regulatory authorities, i.e. off-label use, at least in the short-term while more experience is gained with new biosimilar products. KOLs not surprisingly were more concerned with clinical considerations, and in most cases will only consider use of a given biosimilar for an extrapolated indication, regardless of their regulatory status, once they are confident of its safety and efficacy in the indications where direct clinical evidence support exists. KOL sensitivity to the issue of indication extrapolation, indeed, can also vary by specialty of the clinician. This topic has been brought to the fore since the European Medicines Agency’s decision in September 2013 to grant infliximab biosimilars Remsima and Inflectra authorization for use in the same indications as their originator Remicade [7]. These included the gastroenterological conditions Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis, based on extrapolation of rheumatoid arthritis and ankylosing spondylitis clinical trial data (phase 3 and phase 2, respectively). Conversely, Health Canada subsequently approved the infliximab biosimilars for use in all of the originator’s indications except Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis [8]. As a result, gastronenterologists may well have had different perspectives on the topic of indication extrapolation than the rheumatologists and haematologist oncologists interviewed as part of this research.

While payers’ range of comfort in providing access to biosimilars varied by market, within the respective markets payers were more comfortable providing access to biosimilars of less complex products like epoetin alfa, or products with which they already had experience with a biosimilar version, while expressing lower levels of comfort in providing access to more complex biosimilar monoclonal antibodies. Payers’ expected cost savings from biosimilars also varied by market, and reflected the extent to which they expected regulators to put in place specific mechanisms to assess new biosimilar products for bioequivalence. As a result, Mexican payers cited lower expected cost savings than their Argentinian counterparts, who expected ANMAT to enact appropriate measures to enable biosimilars to appropriately demonstrate bioequivalence without incurring the full cost associated with the clinical programme of a novel biological.

As for expected discount requirement, payers’ responses ranged from as low as 5% in Mexico, where biosimilars at social insurers like IMSS and ISSSTE compete on equal footing as their reference brands in reverse auction tenders that include both branded and biosimilar competitors, to 10–30% in Brazil and Argentina. Discount levels to win public SUS tender contracts in Brazil, which like public payer tenders in Mexico are conducted at the molecule level, could potentially be even lower in the future as biosimilars gain more experience in the market. At discounts below the branded originator greater than 20% in Argentina and 35% in Brazil, payers reported that, based on their experience with the private market, private payers would start to implement measures to require patients to first try a biosimilar before reimbursing use of its branded equivalent or else pay the difference in cost between the biosimilar and branded biological to use the brand first. While KOLs across markets expressed a strong preference to prescribe branded biologicals over biosimilars, they consistently noted that payer access restrictions or patient affordability limitations could cause them to prescribe biosimilars instead of branded biologicals at discounts less than 20–25%. They went on to note that once they become comfortable that biosimilars indeed have bioequivalent safety and efficacy that they likely will consider them first for all patients at discount levels greater than 20–25%. This finding was consistent across the different countries included in this research despite significant differences in payer concentration, funding and public versus private payer membership seen across their respective healthcare systems.

Our study is subject to some limitations, including the small number of interviews. Because payer respondents were from different payer systems in the countries studied, they may have had different expectations regarding the entry of biosimilars in their regional market. For example, Brazilian payers were advisors primarily for the public system, which provides the majority of biologicals, while Argentinian payers were from a provincial and private insurer, representing multiple payer systems. These differences may affect the interpretation of our findings.

In conclusion, while legitimate questions exist regarding the safety and efficacy of biosimilars, our small, selected sample of payers and physicians across Latin American markets noted the potential for biosimilars to provide cost savings for patients and healthcare systems. Although payers and physicians alike cited the importance that bioequivalent safety and efficacy be proven through head-to-head demonstration of biosimilarity to branded originator products, they ultimately will look to regulators for guidance on which products have provided sufficient evidence, and for which indications. While the level of discount versus the branded originator required for public sector access varied by market, once proven and if offered at discounts greater than 20–25% below their originators, biosimilars have the potential to gain broad penetration not only with cost-sensitive public payers but also with clinically-oriented physicians across Latin American markets.

Disclosure of financial interests: Mr Erik Sandorff, Dr André Vidal Pinheiro and Ms Daniele Severi Bruni are employees of ICON Commercialisation Strategy & Science, an ICON plc company that provides consulting services to biopharmaceutical clients. No client sponsorship was involved with this project. Dr Ronald J Halbert was an employee of ICON Commercialisation Strategy & Science during the time the work was done. Adjunct Professor Valderilio Feijó Azevedo participates in Pfizer and Merck Serono’s international advisory boards for biosimilars. He declares not to have received any payment to collaborate on this project. ICON Commercialisation Strategy & Science provided financial support to this project.

Competing interest: The authors have indicated that they have no conflicts of interest with regard to the content of this article.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Erik Sandorff1, MA, MBA

André Vidal Pinheiro1, PhD

Daniele Severi Bruni1, MPhil

Ronald J Halbert2, MD, MPH

Adjunct Professor Valderilio Feijó Azevedo3,4, MD, PhD, MBA

1ICON Commercialisation Strategy & Science, North Wales, PA 19454, USA

2University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA), School of Public Health, Los Angeles, CA 90095, USA

3Department of Internal Medicine, Hospital de Clínicas, Federal University of Paraná, 224 Rua Alvaro Alvin, Casa 18 Seminário, Curitiba-Paraná PR 80740-260, Brazil

4Edumed Health and Educational Research, Curitiba, Brazil

References

1. Befrits G. The case for biosimilars–a payer’s perspective. Generics and Biosimilars Initiative Journal (GaBI Journal). 2013;2(1):12. doi:10.5639/gabij.2013.0201.009

2. Höer H, de Millas C, Häussler B, Haustein R. Saving money in the European healthcare systems with biosimilars. Generics and Biosimilars Initiative Journal (GaBI Journal). 2012;1(3-4):120-6. doi:10.5639/gabij.2012.0103-4.036

3. Castanheira LG, Barbano DB, Rech N. Current development in regulation of similar biotherapeutic products in Brazil. Biologicals. 2011;39(5):308-11.

4. Kirchlechner T. Current regulations of biosimilars in the Latin American region. Paper presented at: 3rd Annual Drug Information Association (DIA) Latin American Regulatory Conference; 12–15 April 2011; Panama City, Panama.

5. Azevedo VF, Sandorff E, Siemak B, Halbert RJ. Potential regulatory and commercial environment for biosimilars in Latin America. Value in Health Regional Issues. 2012;1(2):228-34.

6. SEGOB. NORMA Oficial Mexicana de Emergencia NOM-EM-001-SSA1-2012, Medicamentos biotecnológicos y sus biofármacos. Buenas prácticas de fabricación. Características técnicas y científicas que deben cumplir éstos para demostrar su seguridad, eficacia y calidad. Etiquetado. Requisitos para realizar los estudios de biocomparabilidad y farmacovigilancia. 2012 Sep 20 [homepage on the Internet]. [cited 2015 Feb 5]. Available from: http://dof.gob.mx/nota_detalle.php?codigo=5269530&fecha=20/09/2012

7. European Medicines Agency. Inflectra. EMA/402688/2013 EMEA/H/C/002778 [homepage on the Internet]. 2013 Jul 19 [cited 2015 Feb 5]. Available from: http://www.ema.europa.eu/ema/index.jsp?curl=pages/medicines/human/medicines/002778/human_med_001677.jsp&mid=WC0b01ac058001d124

8. Health Canada. Inflectra. DIN: 02419475 002778 [homepage on the Internet]. 2015 [cited 2015 Feb 5]. Available from: http://webprod5.hc-sc.gc.ca/dpd-bdpp/info.do?code=90410&lang=eng

|

Author for correspondence: Erik Sandorff , MA, MBA, 2100 Pennbrook Parkway, North Wales, PA 19454, USA |

Disclosure of Conflict of Interest Statement is available upon request.

Copyright © 2015 Pro Pharma Communications International

Permission granted to reproduce for personal and non-commercial use only. All other reproduction, copy or reprinting of all or part of any ‘Content’ found on this website is strictly prohibited without the prior consent of the publisher. Contact the publisher to obtain permission before redistributing.

Source URL: https://gabi-journal.net/payer-and-physician-evidence-and-discount-requirements-for-biosimilars-in-three-latin-american-countries.html

Author byline as per print journal: Valderilio Feijó Azevedo, MD, PhD; Eduardo Mysler, MD; Alexis Aceituno Álvarez, PharmD, PhD; Juana Hughes, MSc; Francisco Javier Flores-Murrieta, PhD, FCP; Eva Maria Ruiz de Castilla, MS, MAA, PhD

|

Abstract: |

Submitted: 31 March 2014; Revised: 27 May 2014; Accepted: 4 June 2014; Published online first: 17 June 2014

With the emergence of biosimilars as a new class of biotherapeutic agent, the use of these drug products in Latin America has become a focus of attention. To aid policymakers and regulatory authorities, the Americas Health Foundation (AHF) convened a group of experts on biosimilars to discuss the major issues related to the use of these products in Latin America. AHF relied on a number of sources to identify appropriate and potential panel members. Suggestions were received from other organizations and from individuals who had been recommended by other experts. Adjunct Professor Valderilio Azevedo was the lead contact and helped recommend and recruit other panel members so as to achieve a diverse composition of workgroup members. The AHF received a non-restrictive grant from Roche, who had no role in the decision to select panel members for the workgroup. AHF was responsible for the selection of the topic and subsequent subtopics in conjunction with the lead panel member. AHF was responsible for all logistics and expenses, including travel, hotel, and honorariums.

The facilitator for the workgroup discussion was Dr Richard Kahn, the former Chief Scientific and Medical Officer for the American Diabetes Association, who has moderated a number of consensus conferences for AHF in the past. The meeting was held over a two and a half day period of intensive and concentrated time, including 10–12 hour days. Each panel member was responsible for preparing a draft paper on his or her respectively assigned subtopic. These papers became the basis for the subsequent discussions and the final recommendations. In compiling the individual papers into a cohesive manuscript, every sentence was read, reviewed, discussed and agreed upon by the entire workgroup. Questions, comments, suggestions and disagreements were all aired openly and fully until consensus was reached.

The result of this discussion was the production of this manuscript. In this manuscript, we review the critical points in the development of regulations for the approval of biosimilars in Latin America and outline recommendations for the best implementation of regulations throughout the region.

The name biopharmaceuticals has been coined for medicinal products that contain biotechnology- or biology-derived substances (mainly proteins and polysaccharides) as their active components. There are many examples of this class of product, including human erythropoietin, insulin, growth hormone, cytokines and a number of monoclonal antibodies [1, 2].

Biotechnology processes such as recombinant DNA, controlled gene and antibody expression are the most common methods to manufacture biopharmaceuticals [3]. The manufacturing process of biopharmaceuticals plays a key role because the process itself is critical to the nature of the final product. Small differences in the design and execution of a manufacturing process can have a large influence on the clinical profile of the final product. In fact, due to the complexities associated with the manufacturing process, most biopharmaceutical manufacturers obtain a patent for the production process and not necessarily for the biotherapeutic product itself [4, 5].

Biosimilars are medicines similar to biopharmaceuticals that have already been approved. In other words, a biosimilar is a version of a previously approved biological medicine termed the reference product. Several names are given to biosimilars in different parts of the world, such as biocomparables, biological products, ‘follow-on biologics’, follow-on protein products, or subsequent entry biologicals [1, 6–8].

Biosimilars are not the same as generic versions of chemical synthesis-derived drugs. This is because the complexity of the manufacturing process, the heterogeneity of the final product, the active component itself, and other factors may not be identical to the reference product [9]. Biosimilars are expected to reduce drug expenditure, assuming that they achieve the same clinical results as those of the reference product [4, 10].

In general, a manufacturer of biosimilars must establish that its product is similar enough to a reference product to serve as an alternative to it. Comparative quality, efficacy and safety studies are all required and must be performed in a step-wise manner to demonstrate biosimilarity.

Considering the complexity of biotherapeutic products and the limitations imposed by analytical techniques to determine whether they are indeed identical to the reference product, the approval of biosimilars must rely on demonstrating comparable clinical safety and efficacy [4, 11, 12]. To evaluate comparability, the manufacturer should first perform complete physico-chemical and biological characterization of the biosimilar on a head-to-head comparison with the reference product. Physico-chemical properties can be assessed by the primary or higher order structure using methods such as HPLC-mass spectrometry or NMR (nuclear magnetic resonance), whereas biological activity, being a measure of function, will be complementary to the physico-chemical description [13]. Cell-based assays and animal studies including pharmacodynamics and toxicity should be performed in addition to physico-chemical characterization and receptor binding. The methods used to determine the comparability between the biosimilar and its reference product must be sufficiently selective and specific to detect differences between the two. The importance of such differences can only be ascertained in preclinical and clinical studies [14].

To ensure that a biosimilar coming onto the market has the same clinical safety and efficacy as the original product, regulatory agencies need to establish well-designed pathways to achieve approval. To do this, a risk-based approach in evaluating biosimilarity has been recommended [15]. Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic clinical studies are mandatory and should be done as an independent phase I study or as the initial part of a phase III trial [2]. These studies can help identify differences to the reference product, if they are present.

The route of administration and dosage of a biosimilar must be the same as the reference product. There should be similar efficacy between the biosimilar and the reference product as demonstrated in sufficiently powered, randomized, blinded controlled clinical trials. Hard clinical endpoints are essential. Any major deviation from this design should be justified. Equivalence trials (those that require a superior and an inferior comparative limit) are the preferable option for data comparison. A non-inferiority design may be used in certain circumstances, again when justified [16].

The equivalence/non-inferiority margin should be pre-specified and justified to the regulatory authorities on the basis of clinical relevance. Differences in treatment effects must also be acceptable to the medical community and not have any negative impact in patient care [17]. The indication for use of a biosimilar should reflect the results of the clinical trial showing efficacy and safety. Other indications can be extrapolated according to current guidelines (World Health Organization [WHO]) but whether a biosimilar is appropriate for related diseases, e.g. between various inflammatory diseases, is a complex issue [18, 19]. If a biosimilar achieves an indication for one disease, it cannot automatically be assumed that the product is safe and effective for other indications simply because that is what exists for the reference product. Therefore, scientific evidence for such extrapolation should be assessed.

Another significant issue when designing a clinical trial for biosimilars is which population to choose. For example, not every patient with lymphoma will have the same response to a specific therapy; not all patients with rheumatoid arthritis will have the same response to medications that have the same indication. Patients who are methotrexate resistant do not have the same response to a biological that methotrexate naive patients have [20–22]. When deciding which population to study, the developers of a biosimilar should consider the most sensitive population that would best replicate the original results of the reference product. The intention of the clinical study is not to show the safety and efficacy of the biosimilar per se, as that has already been proven for the reference drug, but to ensure that the biosimilar has similar safety and efficacy.

Since biological agents are often immunogenic, differences between a biosimilar and its reference product may occur. That is why the immunogenicity of a biosimilar is essential to ascertain before ensuring its safety and efficacy [23]. The time to the appearance of an immunogenic reaction, as much as the type of reaction illicited, should be evaluated. Testing should have sufficient sensitivity and must have been previously validated. To determine the immunogenicity of a biosimilar, one-year follow-up pre-licensing data is normally recommended. A shorter follow-up period, e.g. six months, might be justified based on the immunogenic profile of the reference product [24].

Clinical trials rarely have the capacity to identify infrequent or unusual adverse events, so post-marketing surveillance is critical to assure drug safety [2, 15, 24–26]. In order to determine whether adverse effects are associated with a biosimilar or its reference product after approval and widespread use, some means to differentiate between the two drugs should be employed, e.g. traceability. In particular, a physician may in practice substitute the biosimilar for the reference product or, if automatic substitution is allowed, a pharmacist may switch from one drug to the other (biosimilar to original drug or vice versa) without informing or having the consent of the treating physician. In either case, it is important to be able to ascribe the cause of an adverse event to one or the other drug.

In order to understand the regulatory framework in Latin America, it is necessary to know the historical background and worldwide situation. In the early 1980s, the introduction of biopharmaceuticals dramatically changed the treatment of some diseases. Soon after, three Latin American countries – Argentina, Cuba and Mexico – started the production of biopharmaceuticals. At that time, most Latin American countries did not have patent law, which prompted industry to make drugs that were copies of the reference drug. Around the year 2000, when countries belonging to the International Conference on Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Registration of Pharmaceuticals for Human Use (including Europe, Japan and the US) began discussing how to approve ‘follow-on biologics’ because patents were close to expiration, Latin America had about 100 products in the market that were intended copies of reference products and registered as generics.

Under these conditions, the first regulation needed was to define the pathway for a biopharmaceutical to be approved, separate from a generic drug. Brazil and Venezuela were the first countries in Latin America to distinguish between the approval process for generics and that for biopharmaceuticals [25]. It was not until 2010 that other countries in Latin America made this distinction and even today there are countries in the region still operating under the original guidelines. For countries in the region that have regulations for the approval of biosimilars, the WHO guidelines [2] have been adopted. Although countries have adopted these regulations in general terms, there are many countries whose regulations differ from WHO.

A significant issue in Latin America is how to re-evaluate products that were previously approved but no longer fit the current criteria for a biosimilar. As mentioned above, intended copies of biologicals have been used in Latin American countries for many years and in general there were no criteria for the establishment of similarity between these products and their reference products. In 2002, Brazil began requiring more robust clinical studies in order for a product to be renewed as a biological product. Today, no country in Latin America requires a previously approved intended copy of biological drug to meet all the requirements now in effect to be considered a biosimilar as proposed by the WHO guidelines.

Two other important challenges remain. One is to improve the active pharmacovigilance system for biosimilars in a region where few adverse effects from any drugs are reported. The other challenge is that despite having comprehensive regulations for the approval of biosimilars, the region needs to develop the necessary infrastructure to evaluate the analytical and clinical information required for approval.

Because biologicals consume a substantial proportion of national healthcare budgets, the financial pressure to adopt biosimilars in each country is high, although each country varies in its propensity to increase access to biosimilars. The intent to promote the local manufacture of biosimilars should not distort the goal of assuring the safety and efficacy of these drugs.

In Mexico, until recently, criteria for the approval of an intended copy of biological drug was the same as for generics, meaning that preclinical and clinical data were not required. That is why in 2011 there were 23 intended copy biological drugs registered in Mexico as generics and more than 100 million doses of treatments using these drugs have been sold from 1993 to 2012. Unfortunately, due to the lack of pharmacovigilance, it has not been possible to establish the risk of using these inadequately evaluated drugs [27]. However, according to new criteria approved in Mexico in 2011, previously licensed drugs must be renewed every five years, and therefore these intended copy biological drugs will have to demonstrate true biosimilarity with physico-chemical, preclinical and clinical studies as well as pharmacovigilance, including detection of immunogenicity. At this time, Mexico has not approved a biosimilar but these intended copy biological drugs have to demonstrate true biosimilarity with physico-chemical, preclinical and clinical studies as well as pharmacovigilance, including detection of immunogenicity. However, several products are currently under evaluation at various steps of the process, and it is expected that at least one of them will be approved this year.

In Brazil, two pathways for the approval of biosimilars have emerged: a ‘comparability’ pathway and an ‘individual development’ pathway. The comparative pathway is almost identical to the WHO guidelines on evaluation of Similar Biotherapeutic Products (SBP) [2]. In the ‘individual development’ pathway, quality issues and clinical study requirements are reduced relative to the comparative pathway, but an extrapolation of indications, one important and controversial point regarding biosimilars, is not permitted. The comparability pathway is more rigorous and requires comparative phase I and phase III trials to the reference biotherapeutic product (RBP) and will allow extrapolation into other indications [28, 29]. Copy products that are licensed using the comparability pathway are considered biosimilars. With government support and local production capabilities, the future commercial outlook of biosimilars in Brazil seems very promising. Under the new product development partnerships (PDPs) framework, local companies have made partnerships with international companies with expertise in producing both new biological products and biological products, see ‘Glossary of Terms’ below. The resulting products have a shorter timeline to approval and they also have a five-year exclusivity to sell their product to the Brazilian Government.

In contrast to most other countries in the region, Argentina is a major manufacturer of biopharmaceuticals – new biological products or biological products – not simply a distributor. Argentina has a well-established regulatory pathway for biosimilars [30], yet none have been marketed to date. Other countries in Latin America, such as Ecuador, Panama, Paraguay and Peru, have regulations for the approval of biosimilars. And others, such as Chile, Colombia, Uruguay and Venezuela have published draft proposals. However, implementation of the regulations has proven challenging.

The need for well-defined pathways and regulations for the review, approval and pharmacovigilance of biosimilars, as well as greater transparency into the actions of governments, is still necessary in the region. However, a common issue with guidelines in Latin America is that regulatory authorities across countries require different levels of evidence for the approval of biosimilars.