|

Objective: One of the questions that the advent of biosimilars raises is whether the different nature of biological medicines would also imply the need for a different policy approach by Member States in the European Union (EU). To assess the policy environment the European Biopharmaceutical Enterprises (EBE) conducted a brief descriptive policy survey of pricing and reimbursement policies for off-patent biologicals. |

Submitted: 14 December 2014; Revised: 11 February 2015; Accepted: 12 February 2015; Published online first: 25 February 2015

Pharmaceutical pricing and reimbursement policies aim to improve the rational use of medicines and keep pharmaceutical spending under control [1]. In the European Union (EU), the design and implementation of pharmaceutical policies are in the competence of Member States as laid down in the Treaty [2]. Decisions about price and reimbursement of prescription medicines are usually made by governments but also by social funds or private payers. One particular area of interest for pharmaceutical policy is the off-patent market since, with patent expiration, many follow-on medicines both small-molecule generics and biosimilars can enter the market and compete with the originator products. Approximately, Euros 35 billion are saved yearly by the use of small-molecule generics alone, according to the European Generic medicines Association [3].

As an increasing number of biosimilars will soon be available due to patent expiration, the expectations of Member States to generate savings are high. The market for biological products accounted for Euros 36 billion in 2011 [4]. Biological medicines today account for 27% of all pharmaceutical sales in Europe; eight of the top 10 selling medicines are biologicals [5]. Although this is still much less than the market for non-biological products (Euros 107 billion), growth has been at a rate of 7% while the non-biological products market grew at 1%. Between 2006 and 2014, 21 biosimilars were approved by the European Medicines Agency (EMA); two biosimilars have been withdrawn (2008 and 2012) for commercial reasons. The remaining 19 biosimilars on the market represent 12 authorized biosimilar molecules; by commercial agreement, several of these products are registered under two or more trade names [6, 7]. Today, the majority of biological products are still patent protected and thus not yet exposed to biosimilar competition [8]. However, this will change in the next few years when many top-selling products will lose their patent protection [5].

Pharmaceutical policies for the off-patent market for small-molecule generics traditionally included a variety of measures related to pricing, reimbursement, market entry and expenditure controls but also measures targeting distributors, physicians and patients [1]. Some of the most common policies involve generics substitution, Internal Reference Pricing (including Generic Reference Pricing and Therapeutic Reference Pricing), prescribing by International Nonproprietary Name (INN), often linked with the obligation for pharmacists to dispense the cheapest medicine available with the same INN, and finally also procurement practices, such as tendering, see Table 1.

Biosimilars are not the same as generics, which have simpler chemical structures and are considered to be identical to their reference medicines [9, 10]. One of the questions raised by the advent of biosimilars was therefore whether the different nature of biological medicines was also reflected in a different policy approach in terms of pricing and reimbursement by EU Member States. This question prompted the European Biopharmaceutical Enterprises (EBE) to conduct a biologicals policy survey across EU Member States, including Norway, Serbia and Switzerland.

According to EMA, approved biosimilars and their respective reference medicinal products are expected to have the same safety and efficacy profile and are generally used to treat the same conditions. Nevertheless, due to the specific nature of biological medicines, questions have arisen about their suitability for substitution, see Table 1. These questions have been subsequently mentioned or discussed in various documents. The Questions and Answers of EMA and the Guideline on Similar Biological Medicinal Products state that the agency’s evaluations do not include recommendations on whether a biosimilar should be used interchangeably with its reference medicine [11]. The document further states that for questions related to switching from one biological medicine to another, patients should speak to their doctor and pharmacist. The EMA Procedural Advice specifies that the decisions on interchangeability and/or substitution rely on national competent authorities and are outside the remit of EMA’s Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP). [12]. EU Member States have access to the scientific evaluation performed by the CHMP and all submitted data in order to substantiate their decisions. Whether biosimilars can or should be used interchangeably is therefore left to the responsibility of each Member State. This approach is echoed by the Biosimilars Working Group of the Platform on Access to Medicines in Europe which excluded a discussion on the substitution of biosimilars from their terms of reference [13].

As a consequence from the medical implications of biological medicines, literature suggested that biosimilar competition would most probably differ from small-molecule generics competition [14]. But various reasons for this include also development and production costs for biological medicines, more complex regulatory and scientific reviews in the marketing authorization process, additional pharmacovigilance requirements, and increased efforts in education of prescribers. The latter, education and understanding by stakeholders, was also one of the key elements mentioned in a recent GfK report about the factors needed to create a sustainable European biosimilar medicines market [15].

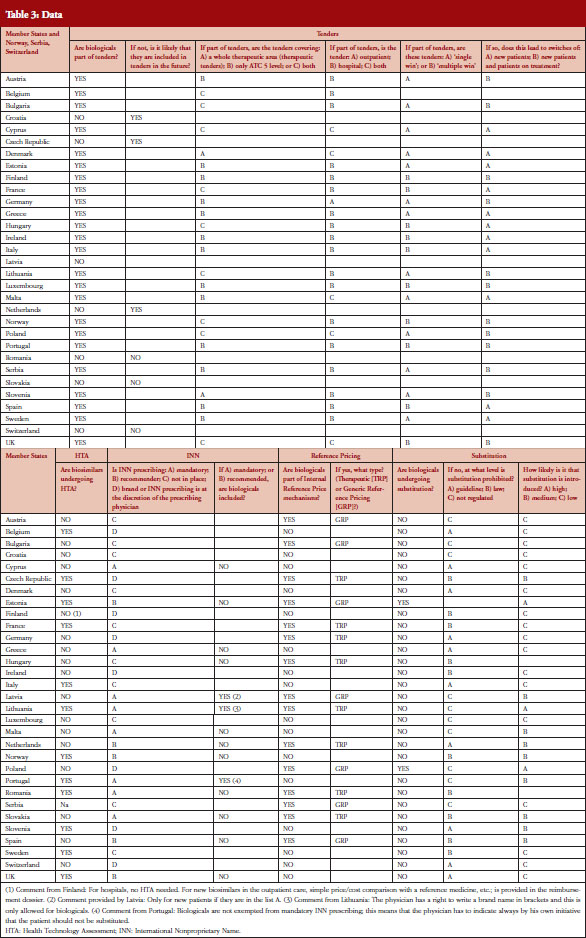

EBE conducted a survey in 31 countries, the 28 EU Member States plus Norway, Serbia and Switzerland. The questionnaire contained 24 questions about the following five policy areas: Tendering, Health Technology Assessment (HTA), INN prescribing, Internal Reference Pricing, and Substitution, see Table 2. The policy areas were selected based on a list of 23 different policies discussed in the Economic Paper 461 ‘Cost-containment policies in public pharmaceutical spending in the EU’ of the Directorate-General for Economic and Financial Affairs (DG ECFIN) [1]. For some of the policies, specific definitions were provided, see Table 1.

The survey questionnaire was developed by the EBE Biosimilars Working Group and focuses on the most relevant policies which: a) applied to the off-patent market; and b) were of specific relevance for biological medicines. As a consequence, policies establishing or allowing substitution were of main interest, e.g. Internal Reference Pricing, INN prescribing or tendering. In addition, as the intention was to gain a brief descriptive overview of a range of different policies as well as a complete and comparable coverage for Europe, the questionnaire focused on a limited number of questions, 24 in total.

Information for specific countries was based on individual comments or available literature and was used to supplement the findings. Finally, the survey included only questions about biological medicines and did not collect information about generics policies. The questionnaire was available in English only.

To pilot the survey instrument, EBE members shared the questionnaire with their respective company affiliates. Following their initial feedback the questions were adapted where necessary. The questionnaire was then sent to national pharmaceutical associations (two mailings with a third mailing to associations which had not yet responded). For five associations, individual phone calls were held to ensure clearer understanding of the responses. The survey did not include any reimbursement or payments for participation.

EBE received responses from 29 national pharmaceutical associations (a 94% response rate) and from two member companies (6%); the latter submitted data from Malta and Romania. Data was collected between September 2013 and March 2014.

Substitution

Nearly two thirds, i.e. 20 out of 31 countries have either laws or guidelines in place that prohibit substitution of biological medicines, see Figure 1. However, substitution of biological medicines at the pharmacy-level can happen in two out of 31 countries (Estonia, Poland). No change of the current policies is expected in the near future and more than half of the respondents (16 out of 28 responses received) considered the possibility of introduction of substitution as unlikely.

It has to be noted that the French Parliament passed into law the 2014 Social Security Bill (PFSS) in December 2013 that contains provisions to permit a restricted form of pharmacy-level substitution for ‘naïve patients‘, i.e. limiting any substitution of any similar biologicals medicines to those patients who are being started on a new treatment course [16]. The law makes clear that patients who have already commenced treatment must not have their medicine substituted by a pharmacist [17]. Currently, the implementation of this measure is still being developed.

A different situation exists in Poland: the Polish reimbursement law does not distinguish between small-molecule generics and biosimilars, including for the purposes of applying its pharmacy-level substitution policy. Under current arrangements, a medicine can be substituted with another when it satisfies specific criteria, including that the products contain the same active substance (defined as same INN), are reimbursed for the same indication and are considered therapeutically equivalent (defined as non-inferior safety and efficacy) [18]. On this basis, the Polish authorities authorize a change in the treatment for patients to infliximab biosimilar from the infliximab originator, and shifting patients from one to another infliximab product does not require the direct supervision of the physician [19].

While only clarified in a letter, in applying its substitution policies to biological medicines, Poland is out of step with nearly all EU countries. France, Germany, Italy and Spain have all declared that similar biological medicines cannot be substituted at the pharmacy level [16, 20–22]. France and Italy have explicitly identified initiating or ‘naïve’ patients as the appropriate population for substitution, stressing the principle of continuation of therapy.

Tendering

In the majority of countries, biological medicines are subject to tenders (24), see Figure 2. In 13 of them the scope is ATC 5, i.e. substance-level only. The majority of tenders with biologicals are hospital tenders only (18). In 12 (23 responses received) countries it is possible that patients on a given treatment are changed to a different product due to tender outcomes. Many respondents reported that ‘usually’ physicians are involved in the decision-making. Respondents from Germany, for example, noted that the tendering may lead to switches but this was not systematic and would rather depend on the decision of the treating physician.

Health Technology Assessment (HTA)

In 12 out of 29 countries biosimilar medicines undergo HTA. In Finland, biosimilars do not undergo HTA in hospitals but do in the outpatient care setting where a simple price-cost comparison with all other medicinal products used for treating the same disease, including the reference medicine, is undertaken. Slovakia has no requirement for HTA for biosimilars. However, if a biosimilar applies for pricing and reimbursement in an indication for which the reference product is not reimbursed then HTA is required.

INN prescribing

Prescribing biological medicines by INN can lead to substitution of patients on treatment since the INN used by the biosimilar is in most cases the same as the one designated by World Health Organization (WHO) for the reference product. While INN prescribing is mandatory or recommended in 13 out of 31 countries, the large majority of countries have introduced mechanisms to exempt biological medicines from prescribing by INN.

In practice, the distinction between small-molecule generics and biologicals – off-patent originators and biosimilars – is often blurred. UK has a strong tradition of INN prescribing and physicians also apply this to biologicals so that this common practice may result in unintentional substitution of biological medicines. In Lithuania, the INN should be used for all new medications included in the ‘List A‘ (interchangeable) with the brand name in brackets. The biosimilar infliximab and the reference product have been part of that list since January 2014. Other biologicals; however, are not on that list and in those cases the brand name can be used. Finally, in Portugal, biologicals are not exempted from mandatory INN prescribing; this means that the physician has to indicate, always by his/her own initiative, that the patient’s medication should not be substituted.

Internal Reference Pricing (IRP)

In almost half of the countries (15) biologicals are included in IRP. Eight of these countries apply Therapeutic Reference Pricing, creating reference groups at the level of the therapeutic class or higher (ATC 4 or higher). Six countries have reference pricing at active substance level (ATC 5; Generic Reference Pricing) in place, see Figure 3. Other countries may have excluded biologicals explicitly from IRP or do not have this policy at all [23].

IRP typically means determining the maximum price for medicinal products and the maximum reimbursement rate for each medicine by grouping them and calculating the price (average, lowest, etc., see Table 1). In six of 15 countries switches can happen due to IRP.

The survey has several limitations. As the intention was to get a brief descriptive overview of a range of different pricing and reimbursement policies for biological medicines across Europe, the questionnaire was kept brief and limited to 24 questions. The survey included only questions about biological medicines and did not poll generics policies in the respective countries. Although such a comparison would have been interesting in light of the different uptake patterns, it would have made the survey unwieldy and likely would have made it very difficult to get a timely and complete response rate. However, this is clearly an area for further research and we hope that this initial review contributes to that pursuit.

We also acknowledge that the questions, see Table 2, were general by nature and were not able to probe the details and interdependencies around those policies. However, many respondents added country-specific comments.

Another limitation is that we did not differentiate between substitution of new patients and patients on treatment as this was less relevant when the survey started. However, to ensure that the main results are meaningful we have presented the responses to the questions, which could be clearly interpreted. For substitution, the results presented are for the question of what kind of regulatory measures in terms of prohibiting substitution were in place, i.e. laws, guidelines or no regulation at all.

The results of this initial EBE policy survey show that countries differ in terms of pharmaceutical policies for biological medicines. A majority of the countries have specific policies in place acknowledging the different nature of biological medicines compared with small-molecule medicines.

At the same time, there is also a great variation between countries and the level of detail in their respective policy frameworks. Ten countries have no explicit regulation concerning substitution of biological medicines so there is a risk that other policies or recommendations could lead to unintended patient treatment changes. However, this does not necessarily mean that biosimilar substitution would not be regulated in these countries. Sometimes it is regulated at a higher level as for example in Austria where doctors must prescribe all medicinal products by brand name and pharmacists must dispense the prescribed medicinal product in a valid prescription. Therefore, pharmacists cannot legally substitute prescribed medicinal products at their own discretion [24, 25]. Noteworthy also is the fact that even some of the most recent literature discussing pharmaceutical policies and cost containment do not mention biosimilars at all or if so only very briefly [1, 26–28].

Traditionally, substitution has played an important role in the off-patent market for small-molecule generics. Generics substitution is used in many countries to increase market efficiency: in 2012 it was mandatory in eight, indicative, i.e. not required but encouraged, in 14 and disallowed in seven EU Member States [1]. For biosimilars, the situation looks different as explained above: biosimilars are not the same as generics, and EMA’s evaluations do not include recommendations as to whether a biosimilar should be used interchangeably with its reference medicine but rather leave the decision to Member States. Aside from the specific situations in France and Poland discussed above, according to the EBE survey no Member State requires substitution.

Whether this will change remains to be seen. The recently launched study that is supported by the Norwegian Government to assess a one-time switch from the originator biological to its biosimilar product will not assess interchangeability [29]. However, the conduct of such a study suggests, the authors believe, that scientific evidence should be a requirement for allowing a change in a treatment with a biological medicine. The fact that interchangeability is mentioned in the EMA documents but not part of the biosimilar regulatory assessment by EMA, coupled with the different regulations in Member States, indicates that the decision about the advisability of substitution is not straightforward.

Questions concerning substitution have implications for many other pharmaceutical policies including tenders, INN prescribing and IRP. In the small-molecule generics market such policies aim at substituting patients using the sole criterion of price to ensure that the cheapest available medicine with the same INN is used, e.g. Poland. To prevent substitution of biological medicines for non-medical reasons several organizations have taken positions on tendering of biological medicines where they suggest that tenders have to be carefully designed to ensure that patients on biological treatments are not automatically substituted [30, 31].

To create savings and ensure an efficient off-patent market for biological medicines competition is a critical factor. The Consensus Information Document [13] which was developed by a multi-stakeholder project group, in close cooperation with the Commission services, states in this regard that: ‘It is important to note that biosimilar market uptake has been possible despite the fact that substitution between the biosimilar and its reference medicinal product is not practiced at the pharmacy level’ [13].

The same publication mentions potential factors involved in uptake, such as physician perception of biosimilar medicines, patient acceptance of biosimilar medicines, local pricing and reimbursement regulation, procurement policies and terms, and concludes: ‘It is thus essential that physicians and patients share a thorough understanding of biological medicines, including biosimilar medicines, and express confidence in using either type of therapy. This can be achieved by maintaining a robust regulatory framework and effective risk management, transparency with regard to biological medicinal products, and continued education on biological medicines, including biosimilar medicines’ [13]. The fact that multiple factors play a role in competition in the off-patent market for biologicals has been confirmed by a recent report from IMS Health [5].

That uptake is also correlated with culture was reported by Grabowski et al. when comparing different markets with regard to biosimilars: uptake in countries with low rates of generics competition like France and Italy seem also to have a lower uptake of biosimilars – in contrast to countries like Germany or the UK [32]. The only exemption was in the G-CSF market, and there have been some hypotheses put forth about the reasons for this difference, which focus on its short-term therapeutic use as supportive care. In changing behaviour trust plays an important role; good information is one element needed to create trust [13]. A recently published survey among European physicians confirmed the need for more and better education [33].

Off-patent market policies for pricing and reimbursement of biological medicines should be formulated in a holistic manner, i.e. reflect the full ecosystem of pharmaceutical innovation. Instead of pure uptake measures they should promote competition, which means they should ensure proper exclusivity rights but also swift market entry of competitors after Marketing Authorization. Such competition has to be sustainable and should generate savings for healthcare systems without compromising medical standards. The sustainability of biologicals policies becomes particularly relevant as recent research of Leopold et al., for example, suggests that in the field of small-molecule generics policy changes happened very frequently due to the economic recession: between 2008 and 2011 economically stable countries implemented two to seven policy changes each, whereas less stable countries implemented 10 to 22 each [34].

From a broader perspective, early access to innovative medicines and incentives for sustainable medical innovation, e.g. data exclusivity, sound demand-side policies, also need to be ensured. The differences between biosimilars and small-molecule generics should also be reflected in the policy approach. Efficient and sustainable markets for biologicals after patent expiry require a balance between payers’ policies, the attitudes of healthcare providers and patients, and sound competition. Policies need to be sustainable, i.e. create trust among healthcare providers and patients through information and a strong regulatory framework, e.g. EMA, and reflect the ‘Cost of Development’, regulatory requirements (including post marketing) and facilitate long-term competition.

This first descriptive EBE survey of pricing and reimbursement policies for biological medicines indicates that nearly all jurisdictions have policies in place that reflect the different nature of biological medicines. However, policies and their implementation vary among different jurisdictions.

Competing interests: This paper is authored and funded by European Biopharmaceutical Enterprises (EBE) and represents the policies of the organization.

EBE is the European trade association that represents biopharmaceutical companies of all sizes operating in Europe. Membership is open to all companies using biotechnology to discover, develop and bring new medicinal products to market. For more information: www.ebe-biopharma.eu/

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Virginia Acha, DPhil, Director Global Regulatory and R & D Policy – Europe, Middle East and Africa, Amgen

Piers Allin, Director Regulatory Affairs, European Biopharmaceutical Enterprises

Stefan Bergunde, Diplom-Kaufmann (MBA), Strategic Initiatives Europe, AbbVie

Fabio Bisordi, MSc, Regulatory Franchise Head, F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd

Alexander Roediger, MA USZ, Executive MBA HSG, Director European Union Affairs, MSD Europe Inc

References

1. European Commission. Carone G, Schwierz C, Xavier A. Cost-containment policies in public pharmaceutical spending in the EU. Economic Papers 461. 2012 [homepage on the Internet]. 2012 Sep 27 [cited 2015 Feb 11]. Available from: http://ec.europa.eu/economy_finance/publications/economic_paper/2012/pdf/ecp_461_en.pdf

2. European Union. Eur-Lex. Treaty of the Functioning of the European Union, Art. 168(7); Official Journal (9.5.2008) C 115/47-199 [homepage on the Internet]. [cited 2015 Feb 11]. Available from:http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:12012E/TXT

3. European Generics medicines Association. Napolitano S. EGA Fact Sheet on generic medicines. Every year Generic medicines bring savings of € 35 BN to the EU 27 [homepage on the Internet]. 2013 Nov 13 [cited 2015 Feb 11]. Available from: http://www.egagenerics.com/images/EGA_factsheet_09.pdf

4. European Commission. IMS. Dunn C. Biosimilar accessible market: size and biosimilar penetration. Prepared for EFPIA-EGA-EuropaBio, April 2012 [homepage on the Internet]. [cited 2015 Feb 11]. Available from: http://ec.europa.eu/enterprise/sectors/healthcare/files/docs/biosimilars_imsstudy_en.pdf

5. IMS Health. Assessing biosimilar uptake and competition in European markets. October 2014 [homepage on the Internet]. 2014 Oct 8 [cited 2015 Feb 11]. Available from: http://www.imshealth.com/imshealth/Global/Content/Corporate/IMS%20Health%20Institute/Insights/Assessing_biosimilar_uptake_and_competition_in_European_markets.pdf

6. European Medicines Agency. European public assessment reports [homepage on the Internet]. [cited 2015 Feb 11]. Available from: http://www.ema.europa.eu/ema/index.jsp?curl=pages%2Fmedicines%2Flanding%2Fepar_search.jsp&mid=WC0b01ac058001d124&searchTab=searchByAuthType&alreadyLoaded=true&isNewQuery=true&status=Authorised&keyword=Enter+keywords&searchType=name&taxonomyPath=&treeNumber=&searchGenericType=biosimilars&genericsKeywordSearch=Submit

7. Walsh G. Biopharmaceutical benchmarks 2014. Nat Biotechnol. 2014;32(10):992-1000.

8. GaBI Online – Generics and Biosimilars Initiative. Biosimilars approved in Europe [www.gabionline.net]. Mol, Belgium: Pro Pharma Communications International; [cited 2015 Feb 11]. Available from: www.gabionline.net/Biosimilars/General/Biosimilars-approved-in-Europe

9. European Medicines Agency. Questions and answers on biosimilar medicines (similar biological medicinal products). EMA/837805/2011. 27 September 2012 [homepage on the Internet]. 2012 Sep 27 [cited 2015 Feb 11]. Available from: http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Medicine_QA/2009/12/WC500020062.pdf

10. Weise M, et al. Biosimilars: the science of extrapolation. Blood. 2014;124(22):3191-6.

11. European Medicines Agency. Guideline on similar biological medicinal products. CHMP/437/04 Rev 1. 23 October 2014 [homepage on the Internet]. 2014 Oct 30 [cited 2015 Feb 11]. Available from: http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Scientific_guideline/2014/10/WC500176768.pdf

12. European Medicines Agency. EMA Procedural advice for users of the Centralised Procedure for Similar Biological Medicinal Products applications. EMA/940451/2011. October 2014 [homepage on the Internet]. 2014 Oct 29 [cited 2015 Feb 11]. Available from: http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Regulatory_and_procedural_guideline/2012/04/WC500125166.pdf

13. European Commission. What you need to know about biosimilar medicinal products. A consensus information document [homepage on the Internet]. 2013 Apr 24 [cited 2015 Feb 11]. Available from: http://ec.europa.eu/enterprise/sectors/healthcare/files/docs/biosimilars_report_en.pdf

14. Farfan-Portet MI, Gerkens S, Lepage-Nefkens I, Vinck I, Hulstaert F. Are biosimilars the next tool to guarantee cost-containment for pharmaceutical expenditures? Eur J Health Econ. 2014;15(3):223-8.

15. European Generic medicines Association. GfK Market Access. Factors supporting a sustainable european biosimilar medicines market [homepage on the Internet]. 2014 Sep 9 [cited 2015 Feb 11]. Available from: http://www.egagenerics.com/index.php/publications/342-gfk-final-report-factors-supporting-a-sustainable-european-biosimilar-medicines-market

16. Conseil Consitutionnel. Décision n° 2013–682 DC du 19 décembre 2013 [homepage on the Internet]. [cited 2015 Feb 11]. Available from: http://www.conseil-constitutionnel.fr/decision/2013/2013–682-dc/decision-n-2013–682-dc-du-19-december-2013.138972.html

17. European Biopharmaceutical Enterprises. EBE statement on French substitution policy. 24 January 2014 [homepage on the Internet]. 2014 Jan 24 [cited 2015 Feb 11]. Available from: http://www.ebe-biopharma.eu/newsroom/54/22/EBE-statement-on-French-substitution-policy

18. European Commission. Report on a biologics workshop in Warsaw on 13 November 2014. [Biosimilar medicines can be treated as generic medicines with a wider scope of research in comparison to relation to the reference medicines, and therefore they can be applied interchangeably – convinced Igor Radziewicz-Winnicki, Undersecretary of State in the Ministry of Health]. In Polish. [cited 2015 Feb 11]. Available from: http://ec.europa.eu/polska/news/141119_leki_pl.htm

19. Ministerstwo Zdrowia. Komunikat MZ-PLA-460-16300-118/BRB/14. 10 June 2014. Pismo MZ-PLA-460–15149–316/BRB/14. Wedlug rozdzielnika. 14 April 2014. [homepage on the Internet]. In Polish. [cited 2015 Feb 11]. Available from: http://www.nfz-wroclaw.pl/download.ashx?id=/45418/pisma%20MZ%20ws%20lek%F3w%20biopodobnych.pdf

20. GKV Spitzenverband. Rahmenvertrag nach §129 Absatz 2 SGB V, Paragraph 4(1), in connection with attachment 1 of the Framework Agreement on Medicinal Products Supply pursuant to Sec. 129 para 2 SGB V. 15 June 2012 [homepage on the Internet]. 2012 Jun 19 [cited 2015 Feb 11]. Available from: http://www.gkv-spitzenverband.de/media/dokumente/krankenversicherung_1/arzneimittel/rahmenvertraege/apotheken/AM_20120615_S_RVtg_129_Abs2.pdf

21. Agenzia Italiana del Farmaco. Position Paper sui farmaci biosimilari (28/05/2013) [homepage on the Internet]. 2013 May 27 [cited 2015 Feb 11]. Available from: http://www.agenziafarmaco.com/it/content/position-paper

22. Agencia Estatal Boletín Oficial del Estado. Spain: Orden SCO/ 2874/2007 of 28 September, Article 1 [homepage on the Internet]. [cited 2015 Feb 11]. Available from: http://www.boe.es/diario_boe/txt.php?id=BOE-A-2007-17420

23. Dylst P, et al. Reference pricing systems in Europe: characteristics and consequences. Generics and Biosimilars Initiative Journal (GaBI Journal). 2012;1(3-4):127-31. doi:10.5639/gabij.2012.0103-4.028

24. Jusline. Rezeptpflichtgesetz, Art. 3 (1c) [homepage on the Internet]. [cited 2015 Feb 11]. Available from: http://www.jusline.at/Rezeptpflichtgesetz_(RezPG).html

25. Österreichische Apothekerkammer. Apothekergesamtvertrag, Art. 2 [homepage on the Internet]. [cited 2015 Feb 11]. Available from: http://www.apotheker.or.at/internet/OEAK/NewsPresse_1_0_0a.nsf/agentEmergency!OpenAgent&p=4E4DD0F8172AD880C1257142002721F3&fsn=fsStartHomeFachinfo&iif=0

26. European Parliament. Kanavos P, et al. Differences in costs of and access to pharmaceutical products in the EU. 2010 [homepage on the Internet]. 2013 Mar 24 [cited 2015 Feb 11]. Available from: http://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/etudes/join/2011/451481/IPOL-ENVI_ET(2011)451481_EN.pdf

27. Gesundheit Österreich GmbH (GOEG) WHO Collaborating Centre for Pharmaceutical Pricing and Reimbursement Policies. Bouvy J, Vogler S. Background Paper 8.3. Pricing and reimbursement policies: impacts on innovation. 2013 [homepage on the Internet]. 2013 Jun 28 [cited 2015 Feb 11]. Available from: http://whocc.goeg.at/Literaturliste/Dokumente/FurtherReading/Bouvy_PriorityMedicines_2013_BP8_3_pricing.pdf

28. World Health Organization. Kaplan W, et al. Priority Medicines for Europe and the World. 2013 Update [homepage on the Internet]. 2013 Jul 8 [cited 2015 Feb 11]. Available from: http://www.who.int/medicines/areas/priority_medicines/MasterDocJune28_FINAL_Web.pdf

29. EU Clinical Trials Register. Clinical trials for 2014-002056-40 [homepage on the Internet]. 2015 Feb 11 [cited 2015 Feb 11]. Available from: https://www.clinicaltrialsregister.eu/ctr-search/search?query=2014-002056-40

30. European Biopharmaceutical Enterprises. EBE Position Paper on tendering of biologicals, including biosimilars. 21 May 2012 [homepage on the Internet]. [cited 2015 Feb 11]. Available from: http://www.ebe-biopharma.eu/documents/3/22/EBE-Position-Paper-on-Tendering-of-Biologicals-including-Biosimilars

31. EuropaBio. EuropaBio’s position on tendering practices in biological medicines [homepage on the Internet]. 2010 Nov 19 [cited 2015 Feb 11]. Available from: http://www.europabio.org/sites/default/files/position/europabio_position_on_tendering_practices.pdf

32. Grabowski H, Guha R, Salgado M. Biosimilar competition: lessons from Europe. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2014;13(2):99-100.

33. EuropaBio. Pan-European survey calls for a shift in policy for biosimilars. 18 March 2010 [homepage on the Internet]. 2015 Feb 11 [cited 2015 Feb 11]. Available from: http://www.europabio.org/press/pan-european-survey-calls-shift-policy-biosimilars

34. Leopold C, et al. Effect of the economic recession on pharmaceutical policy and medicine sales in eight European countries. Bull World Health Organ. 2014;92(9):630-40D.

35. Gesundheit Österreich GmbH (GOEG), WHO Collaborating Centre for Pharmaceutical Pricing and Reimbursement Policies (2015), Glossary; [cited 2015 Feb 11]. Available from: http://whocc.goeg.at/Glossary/PreferredTerms

36. European Biopharmaceutical Enterprises. EBE Position paper on recommendations on the use of biological medicinal products: substitution and related healthcare policies. http://www.ebe-biopharma.eu/priorities/biosimilars

|

Author for correspondence: Alexander Roediger, MSD Europe Inc, 5 Clos du Lynx, BE-1200 Brussels, Belgium |

Disclosure of Conflict of Interest Statement is available upon request.

Copyright © 2015 Pro Pharma Communications International

Permission granted to reproduce for personal and non-commercial use only. All other reproduction, copy or reprinting of all or part of any ‘Content’ found on this website is strictly prohibited without the prior consent of the publisher. Contact the publisher to obtain permission before redistributing.

Source URL: https://gabi-journal.net/what-pricing-and-reimbursement-policies-to-use-for-off-patent-biologicals-results-from-the-ebe-2014-biological-medicines-policy-survey.html

|

Abstract: |

Submitted: 1 September 2014; Revised: 23 September 2014; Accepted: 9 October 2014; Published online first: 22 October 2014

Europe has been instrumental in the global development of biosimilars, with 12 biosimilar molecules approved, marketed as 18 brands in six classes: somatropin, epoetins, filgrastim, follitropin alfa, insulin glargine, as well as the first biosimilar monoclonal antibody (mAb), infliximab (marketed as Inflectra, Remsima), approved in September 2013 [1, 2].

The requirements and procedures for the marketing authorization for medicinal products for human use in Europe Union (EU) are primarily laid down in Directive 2001/83/EC, as amended. This Directive provides distinct legal frameworks for innovator products, small molecule generic products and biosimilar products, dictating the amount of quality, preclinical and clinical data required to support approval and marketing. To the latter point, small molecule generic products whose formulation or manufacturing method have not been modified in any way that may impact the bioavailability [3] do not require any preclinical or clinical trial data of their own as bioequivalence with a reference product (innovator) can be established through in vitro testing alone. For biosimilar products, in contrast, such a formulaic approach cannot be used. The amount of data to be generated is determined in a stepwise approach, directly comparing the biosimilar with the reference product and the outcome informing the next step. This may result in the need for more or less extensive comparative clinical data. Indeed, the European Medicines Agency (EMA) draft revised guideline, ‘Guideline on Similar Biological Medicinal Products’ states that ‘standard generic approach (demonstration of bioequivalence with a reference medicinal product by appropriate bioavailability studies) which is applicable to most chemically-derived medicinal products is in principle not appropriate to biological/biotechnology-derived products due to their complexity’ [4].

The legal framework for biosimilars enabled EMA to pioneer the regulatory review of biosimilars according to a new scientific approach [5]. However, legal and scientific distinction has not been consistently reflected in the product labelling, with there being differences in the level of detail provided.

The Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) appears to have adopted a labelling approach used for small molecule generic products, with only a small distinction made between the product labelling of the reference and generic products for biosimilar products. This is also illustrated with the recent EU approval(s) of Remsima and Inflectra [1, 2], where such an approach was applied.

As defined by EMA [6] the product labelling, in particular the Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC) is a key component of the marketing authorization of all medicines in the EU and the basis of information for healthcare professionals on how to use a medicine safely and effectively. Updates to the SmPC are made throughout the lifecycle of a medicine as new efficacy and/or safety data emerge or change in the safety profile become apparent. The SmPC also forms the basis for the preparation of the Patient Information Leaflet (PIL), which is an important document for relaying information on medicines to patients.

Instructions on what needs to be detailed in the SmPC are provided in the ‘Guideline on Summary of Product Characteristics’ and when read in conjunction with other guidelines clearly defines the level and type of information that should be reflected in SmPC for all products, including biosimilar medicines. Despite there being general guidance pertaining to the content required for the SmPC as discussed, it is acknowledged there is a requirement for further dialogue regarding detailed specific guidance for biosimilars to be developed.

The structure of the SmPC in relation to biosimilars was addressed by the chair and members of the Biosimilar Medicinal Products Working Party (BMWP), Schneider et al. [7] using mAb as the example. The BMWP authors outlined three potential labelling scenarios, see Table 1, to be considered for labelling of biosimilars, ranging from an identical product label to the reference mAb through to a completely distinct label only reflecting data generated for the biosimilar [7]. As each of the labelling scenarios presented had their pros and cons, the BMWP authors were of the opinion that it was not yet clear how best to conclude the matter.

Other groups have also sought to address the issue, including the European Biopharmaceutical Enterprises (EBE) [8], EuropaBio [9] and the Association of the British Pharmaceutical Industry (ABPI) [10].

The EBE welcomes the BMWP’s acknowledgement that adequate scientific information for biosimilars should be provided and in this regard the product label is the essential component for prescribers [7]. This also corresponds with the key learnings from the Process on Corporate Responsibility in the field of Pharmaceuticals, initiated by DG Enterprise that physician perception and patient acceptance impacts biosimilar uptake [11]. It was concluded that a robust regulatory framework, effective risk management, transparency, and continued education would help engender confidence in the appropriate use of innovator biological medicines and biosimilars. To explain their rationale for not distinguishing the reference from the biosimilar label, the BMWP of EMA has emphasized concern that differential product labelling could implicitly suggest a difference between the biosimilar and the reference product. The latter could be prone to misperception by prescribers who could falsely conclude that the level of evidence created to lead to approval of a biosimilar is less than the usually expected standards for a novel product, if the concept of biosimilars is not understood [1].

While the EBE [12] acknowledges the reasons and concerns highlighted by BMWP, the EBE position is that the SmPC would be better served if it were represented by a combination of information from both the biosimilar and the reference product, see Table 1, if the label is different. Such an approach is of crucial importance in developing an understanding and acceptance of biosimilars.

Three possible scenarios for the labelling (including SmPC and PIL) of biosimilars have been described by Schneider et al. [7]. Adaptations of the proposed labelling options of biosimilars are briefly described in Table 1, which gives an overview of the approaches and relevant key considerations:

EBE believes that Approach C is best suited. First of all, the unique considerations that apply to biosimilars (as compared to generics) exclude Approach A as a suitable option because it does not include relevant data the biosimilar manufacturer has compiled for its clinical comparison. Yet prescribers may want to see such biosimilar data alongside that for the originator, as this will explain the basis for which indications have been approved. Furthermore, by using biosimilar data only (Approach B) characterization data is not included, thus neglecting the proof of biosimilarity. This characterization assumes that the long-term safety profile for the reference product should be applied to the biosimilar and that therefore class warnings, etc.; are appropriate for both products. In addition, because Approach B only provides biosimilar data, this also means that the prescriber needs to refer back to the reference product’s label to complete their understanding of the product, and this is not practical. Approach C is the more balanced approach that can enable transparent disclosure of all relevant information related to the biosimilar and the reference product. Furthermore, Approach C is an approach that also allows transparency on where the data generated comes from, either from the originator or from the biosimilar developer and, additionally, which indications are granted by extrapolation.

EBE identifies that there are five important points for consideration, which arise when prescribers refer to the SmPC of a biosimilar, and these should be considered in any policy guidance related to the matter. They are:

In light of the above considerations, EBE maintains that a single sentence added in section 5.1: Pharmacodynamic properties of the SmPC and a reference to the EMA homepage informing the prescriber that the product is a biosimilar and providing reference for further information does not seem to be sufficient. The information refers the reader to the EMA homepage [17], offering no guidance to physicians and patients to help them navigate to the relevant information and documentation.

Besides this, EBE considers that section 5.1 is not the most relevant section for such a statement, as the information applies to the whole product label and not only to pharmacodynamic properties. More importantly, details of pharmacodynamic properties are not reflected in the PIL and there is a lack of transparency informing patients to the fact a product is a biosimilar medicine.

It is acknowledged that the SmPC is the most widely used reference document for physicians, however, there are other important documents published in the EU which provide information about the product and its basis for approval: the European Public Assessment Report (EPAR) which is a summary of the review and conclusions of the scientific assessment by CHMP; and in a patient friendly format: the Patient Information Leaflet. Table 2 below provides a short description of each of these documents.

For recent biosimilar approvals the ‘generic’ approach to labelling has been agreed by EMA and therefore alludes that it has been considered as representing the most appropriate method for communicating information to physicians. While it is acknowledged that the ‘generic’ labelling approach, taken for the recently approved biosimilars, infers that physicians who would like to have an in-depth understanding of the scientific discussion can refer to the published EPAR on their website, it should be noted that these documents have important limitations in their use as vehicles for educating physicians and patients across the EU, see Table 2.

As the full EPAR information is only available in English, this effectively restricts the number of physicians across the EU who can rely on it as a source of information. In practice, the prescriber would need to refer to separate EPARs, the biosimilar(s) and reference product, in order to scrutinise the data generated when deciding whether to switch their existing medication to the biosimilar. If more than one biosimilar product were available, this would further increase the time needed by a physician to evaluate the therapeutic information. Physicians are already dissatisfied with the increasing time they must spend on administrative tasks and paperwork, as this limits their time for face-to-face patient care [18].

EPARs are primarily designed to provide information on how a medicine was assessed by CHMP and to describe scientific conclusions of the relevant Agency committee. Physicians are likely to be unaware that the EPAR document itself is not updated, but rather is complemented by additional documents such as summaries called ‘Procedural steps taken and scientific information after authorisation’ [19].

Recently, the Alliance for Safe Biologic Medicines (ASBM) [20] surveyed 470 prescribers located in France, Germany, Italy, Spain and the UK regarding information sources used for learning about medicines. The respondents were specialists who prescribed biologicals, including nephrologists, rheumatologists, dermatologists, neurologists, endocrinologists and oncologists and so their perspectives reflected hands-on clinical experience with biologicals in a therapeutic setting. The results indicate that among available information sources, EPAR was the least preferred method (19%), while the SmPC was the next most important source document physicians refer to when they need specific details about a product (43%) after published literature.

Whilst EMA, pioneered the biosimilar approval pathway, specific biosimilar product labelling guidelines have as yet to be developed, whereas other countries have already made provisions on how biosimilar product labels should be presented.

When reviewing the situation in the US, Switzerland and Canada, not unexpectedly, it becomes evident that guidance on the content of biosimilar product labels varies from country to country.

United States

In the US, although biosimilars are still to be registered, FDA has recognized the importance of labelling for biosimilars and is working to reduce potential ambiguities by ensuring clear statements within appropriate sections of the Prescribing Information [21]. Section VIII of the FDA draft guidance on scientific consideration in demonstrating biosimilarity states that labelling of a proposed product should include all the information necessary for a healthcare professional to make prescribing decisions, including a clear statement advising that the product approved is a biosimilar and that it has or has not been determined interchangeable with the reference products [22].

Switzerland

In Switzerland, Swissmedic has also been clear in differentiating between the terms ‘reference product’ and ‘comparator product’ in order to emphasise the fact that candidate biosimilars are characterized by documentary reference to the Swiss reference product [23]. The guideline also lays out the responsibilities to keep the PI of the biosimilar up to date is that of the authorization holder. In particular, the authorization holder must actively monitor changes to the safety text of the reference product and must submit either an appropriate application for a variation or provide clear scientific justification if the texts are not to be adapted.

Canada

Health Canada’s approach for their first approved biosimilar mAb (Remsima/Inflectra) approved in January 2014 shows the clearest distinction to the approach that EMA followed, see Table 1. As the guideline states, the sponsor of a biosimilar is not able to utilize the product monograph of the reference biological drug in its entirety as that of its own product [24]. Furthermore, the monograph details additional requirements clarifying that the product is a biosimilar. These include key data on which the decision for market authorization was made, tables showing the results of the comparisons between the biosimilar and reference biological drug, and information on the indications approved for use.

On the basis of the arguments provided, EBE recommends that an approach of greater transparency within the product labelling of the biosimilar be provided. A combination of information on both the biosimilar and the reference product (Approach C) is recommended and to define what this entails, greater dialogue is required between EMA, BMWP, industry, opinion leaders and patients. As EPAR is not a preferred information source, in its current setting, it should not replace the important role of SmPC as the primary point of reference.

EBE is of the position that the generation of detailed specific guidance on the product labelling of biosimilars is of crucial importance to realize consistency and transparency of biosimilar labels, which will lead to a better understanding and acceptance of these products with all stakeholders. Most importantly, consideration should be given to ensuring the SmPC for biosimilars details information most relevant to the prescriber.

Although it will be challenging to achieve an ideal solution which encompasses the needs of all stakeholders, it is preferable that clinicians have ready access to the relevant information regarding biosimilars to enable informed decision-making by physicians and patients and therefore ensures safe and effective use of the medicine. Clearly, further education and dialogue on biosimilar concepts is needed and this is a widely shared agenda. Equally important is the need to build trust together with understanding, and the foundation for this is transparency and open dialogue. To meet these aims, EBE recommends a thorough consultation with all stakeholders to explore the needs and the best approaches for providing appropriate product labelling guidance for biosimilars in the EU.

Competing interests: This paper is authored and funded by the European Biopharmaceutical Enterprises (EBE) and represents the policies of the organization.

EBE is the European trade association that represents biopharmaceutical companies of all sizes operating in Europe. Membership is open to all companies using biotechnology to discover, develop and bring new medicinal products to market.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Keith Watson, AbbVie

Virginia Acha, Catherine Akers, Amgen

Alexander Roediger, MSD

Åsa Rembratt, Novo Nordisk

Edward Hume, Pfizer

Fabio Bisordi, Marloes van Bruggen, Roche

References

1. European Medicines Agency. European public assessment reports: Inflectra. 2013 [homepage on the Internet]. [cited 2014 Sep 23]. Available from: http://www.ema.europa.eu/ema/index.jsp?curl=pages/medicines/human/medicines/002778/human_med_001677.jsp&mid=WC0b01ac058001d124

2. European Medicines Agency. European public assessment reports: Remsima. 2013 [homepage on the Internet]. [cited 2014 Sep 23]. Available from: http://www.ema.europa.eu/ema/index.jsp?curl=pages/medicines/human/medicines/002576/human_med_001682.jsp

3. European Medicines Agency. Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use. Guideline on the investigation of bioequivalence. CPMP/EWP/QWP/1401/98 Rev. 1/Corr++. 20 January 2010 [homepage on the Internet]. 2010 Mar 10 [cited 2014 Sep 23]. Available from: http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Scientific_guideline/2010/01/WC500070039.pdf

4. European Medicines Agency. Guideline on similar biological medicinal products. CHMP/437/04 Rev 1. 22 May 2013 [homepage on the Internet]. 2013 Jun 19 [cited 2014 Sep 23]. Available from: http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Scientific_guideline/2013/05/WC500142978.pdf

5. European Medicines Agency. Guideline on similar biological medicinal products containing monoclonal antibodies—non-clinical and clinical issues. EMA/CHMP/BMWP/403543/2010. 30 May 2012 [homepage on the Internet]. 2012 Jun 11 [cited 2014 Sep 23]. Available from: http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Scientific_guideline/2012/06/WC500128686.pdf

6. European Medicines Agency. How to prepare and review a summary of product characteristics [homepage on the Internet]. [cited 2014 Sep 23]. Available from: http://www.ema.europa.eu/ema/index.jsp?curl=pages/regulation/document_listing/document_listing_000357.jsp&mid=WC0b01ac05806361e1

7. Schneider CK, Vleminckx C, Gravanis I, Ehmann F, Trouvin JH, Weise M, et al. Setting the stage for biosimilar monoclonal antibodies. Nat Biotechnol. 2012;30(12):1179-85.

8. European Biopharmaceutical Enterprises. EBE position paper biosimilars labeling. Summary of Product Information Characteristics and Patient Information Leaflet. 21 April 2013 [homepage on the Internet]. [cited 2014 Sep 23]. Available from: http://www.ebe-biopharma.eu/documents/59/66/EBE-position-paper-on-Biosimilars-Labelling

9. EuropaBio. Statement on labelling of biosimilars. 15 September 2014 [homepage on the Internet]. [cited 2014 Sep 23]. Available from: http://www.europabio.org/positions/europabio-statement-labelling-biosimilars

10. ABPI. ABPI position on biosimilar medicines. February 2013. Available from: http://www.abpi.org.uk/our-work/library/industry/Documents/ABPI%20biosimilars%20position%20paper.pdf

11. European Commission. A consensus information document. What you need to know about biosimilars. April 2013 [homepage on the Internet]. [cited 2014 Sep 23]. Available from: http://ec.europa.eu/enterprise/sectors/healthcare/files/docs/biosimilars_report_en.pdf

12. European Biopharmaceutical Enterprises. Biosimilars [homepage on the Internet]. [cited 2014 Sep 23]. Available from: http://www.ebe-biopharma.eu/priorities/biosimilars

13. Weise M, Bielsky MC, De Smet C, Ehmann F, Ekman N, Giezen J, et al. Biosimilars: what clinicians should know. Blood. 2012;120(26):5111-7.

14. European Medicines Agency. Questions and answers on biosimilar medicines (similar biological medicinal products) 2012 [homepage on the Internet]. 2012 Sep 27 [cited 2014 Sep 23]. Available from: http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Medicine_QA/2009/12/WC500020062.pdf

15. European Commission. Directive 2010/84/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 15 December 2010 amending, as regards of pharmacovigilance, Directive 2001/83/EC on the Community code relating to medicinal products for human use [homepage on the Internet]. 2010 Dec 31 [cited 2014 Sep 23]. Available from: http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=OJ:L:2010:348:0074:0099:EN:PDF

16. Ramanan S, Grampp G. Drift, evolution, and divergence in biologics and biosimilars manufacturing. BioDrugs. 2014;28(4):363-72.

17. European Medicines Agency [homepage on the Internet]. [cited 2014 Oct 9]. Available from: http://www.ema.europa.eu/ema/index.jsp?curl=pages/home/Home_Page.jsp&mid=

18. NHS Confederation. Challenging bureaucracy. 2013 [homepage on the Internet]. [cited 2014 Sep 23]. Available from: http://www.nhsconfed.org/Publications/reports/Pages/challenging-bureaucracy.aspx

19. European Medicines Agency. European public assessment reports [homepage on the Internet]. [cited 2014 Sep 23]. Available from: http://www.ema.europa.eu/ema/index.jsp?curl=pages%2Fmedicines%2Flanding%2Fepar_search.jsp&murl=menus%2Fmedicines%2Fmedicines.jsp&mid=WC0b01ac058001d124&searchTab=searchByAuthType&alreadyLoaded=true&isNewQuery=true&status=Authorised&status=Withdrawn&status=Suspended&status=Refused&keyword=Enter+keywords&searchType=name&taxonomyPath=&treeNumber=&searchGenericType=biosimilars&genericsKeywordSearch=Submit

20. Safe Biologics. Alliance for Safe Biologic Medicines (ASBM). ASBM shares EU survey results at Paris media briefing. 10 June 2014 [homepage on the Internet]. [cited 2014 Sep 23]. Available from: http://safebiologics.org/recent-events.php

21. Davis C, Bowker GM. Labeling standards for biosimilar products. Therapeutic Innovation & Regulatory Science. 2014;48(3):367-70.

22. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Draft guidance for industry on scientific considerations in demonstrating biosimilarity to a reference product. Rockville, MD. February 2012 [homepage on the Internet]. 2012 Feb 8 [cited 2014 Sep 23]. Available from http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Guidances/UCM291128.pdf

23. Swissmedic. Swiss Agency for Therapeutic Products. Questions and answers concerning the authorisation of similar biological medicinal products (biosimilars). 17 February 2014 [homepage on the Internet]. [cited 2014 Sep 23]. Available from: https://www.swissmedic.ch/ueber/00134/00519/01933/index.html?lang=en

24. Health Canada. Guidance for sponsors: information and submission requirements for Subsequent Entry Biologics (SEBS). 2010 [homepage on the Internet]. [cited 2014 Sep 23]. Available from: http://www.hc-sc.gc.ca/dhp-mps/brgtherap/applic-demande/guides/seb-pbu/seb-pbu_2010-eng.php

|

Author for correspondence: Edward Hume, Pfi zer Ltd, Walton Oaks, Dorking Road, Tadworth, Surrey, KT20 7NS, UK |

Disclosure of Conflict of Interest Statement is available upon request.

Copyright © 2015 Pro Pharma Communications International

Permission granted to reproduce for personal and non-commercial use only. All other reproduction, copy or reprinting of all or part of any ‘Content’ found on this website is strictly prohibited without the prior consent of the publisher. Contact the publisher to obtain permission before redistributing.

Source URL: https://gabi-journal.net/tell-me-the-whole-story-the-role-of-product-labelling-in-building-user-confidence-in-biosimilars-in-europe.html

Copyright ©2025 GaBI Journal unless otherwise noted.