Author byline as per print journal: Brian Godman1,2,3,4, BSc, PhD; Andrew Hill5; Professor Steven Simoens6, MSc, PhD; Amanj Kurdi1,7, BSc, PhD; Jolanta Gulbinovič8, MD, PhD; Antony P Martin2,9; Angela Timoney1,10; Dzintars Gotham11, MBBS; Janet Wale12; Tomasz Bochenek13, MD, PhD; Celia C Rothe13; Iris Hoxha14; Admir Malaj15; Christian Hierländer16; Robert Sauermann16, MD; Wouter Hamelinck17; Zornitza Mitkova18; Guenka Petrova18, MPharm, MEcon, PhD, DSci; Ott Laius19; Catherine Sermet20; Irene Langer21; Gisbert Selke21; John Yfantopoulos22; Roberta Joppi23; Arianit Jakupi24; Elita Poplavska25, PhD; Ieva Greiciute-Kuprijanov26; Patricia Vella Bonanno1, BPharm, MSc, PhD; JF (Hans) Piepenbrink27; Vincent de Valk27; Carolin Hagen28; Anne Marthe Ringerud28; Robert Plisko29; Magdalene Wladysiuk29; Vanda Marković-Peković30,31, PhD; Nataša Grubiša32; Tatjana Ponorac33; Ileana Mardare34; Tanja Novakovic35; Mark Parker35; Jurij Fürst36; Dominik Tomek37, PharmD, MSc, PhD; Mercè Obach Cortadellas38; Corinne Zara38; Maria Juhasz-Haverinen39, MScPharm; Peter Skiold40; Stuart McTaggart41; Alan Haycox1, PhD

|

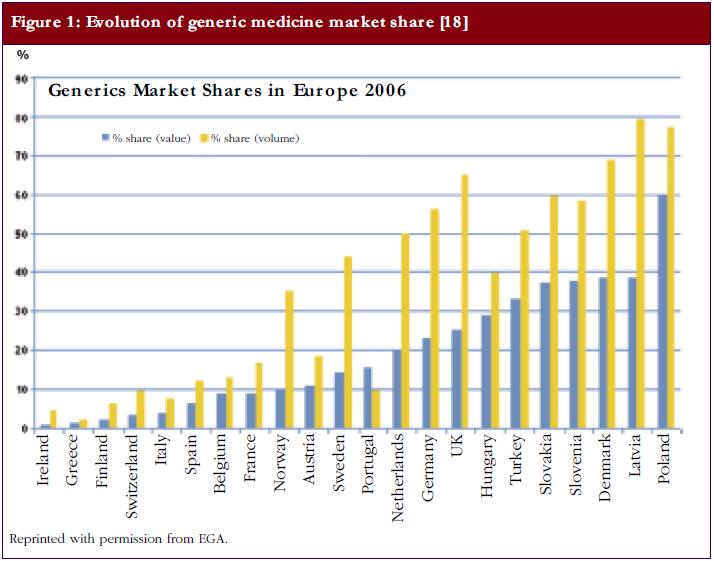

Introduction: There are appreciable concerns among European health authorities with growing expenditure on cancer medicines and issues of sustainability. The enhanced use of low-cost generics could help. |

Submitted: 5 February 2019; Revised: 14 March 2019; Accepted: 20 March 2019; Published online first: 2 April 2019

Despite the limited health gain for most new cancer medicines, their prices have increased appreciably in recent years [1–7]. This is reflected in the price per life year gained for new cancer medicines rising fourfold during the past twenty years after adjusting for inflation [2, 8]. Typically, prices for new cancer medicines are now approximately 6,000 to 9,000 Euros/patient/month and growing [1, 5, 9], with typically higher prices for new cancer medicines in the US versus Europe. As a result of rising prices for new cancer medicines, as well as increased prices for patented cancer medicines [5, 10–12], coupled with the increasing prevalence of cancer [1, 13], spending on cancer medicines in Europe has more than doubled in recent years, rising from Euros 8 billion in 2005 to Euros 19.1 billion in 2014 (at current prices) [14].

As a result, medicines for oncology now dominate pharmaceutical expenditures in developed markets, with projected worldwide sales for oncology medicines in 2017 ranging from US$74 to US$84 billion [15]. Overall, total worldwide sales of oncology medicines are expected to reach US$112 billion (Euros 91 billion) per year by 2020 [16]. Further growth is expected after this with cases of cancer worldwide likely to rise to 21.4 million per year by 2030 [1, 13] coupled more with than 500 companies actively pursuing new oncology medicines in over 600 indications, and looking to benefit from their investment [17]. The cost of cancer care also currently accounts for up to 30% of total hospital expenditure across diseases among European countries, and this is also rising with the launch of new premium-priced cancer medicines [14, 18].

Increasing prices for new cancer medicines, combined with increasing prevalence rates, is putting considerable strain on patients to access cancer treatments and healthcare systems to fund them [19–23]. High reimbursed prices for new cancer medicines certainly in Europe have been enhanced by the emotive nature of cancer, capturing public, physician, and political attention [13, 24–27]. If these trends with new cancer medicines continue, there is a real risk that universal healthcare across Europe will become unsustainable, which will not be in the best interest of any key stakeholder group. Initiatives among European health authorities to help fund future cancer treatments, including new valued high-cost medicines, include encouraging greater use of generic cancer medicines when they become available [12, 26]. This is especially important given the increasing number of cancer medicines that are now out of patent [28]. Initiatives to enhance greater use of generic cancer medicines include encouraging International Nonproprietary Name (INN) prescribing, financial incentives to enhance the prescribing and dispensing of generics versus originators, as well as compulsory generics substitution [29–38]. INN prescribing is supported by multiple publications showing no difference in effectiveness and safety between generics and originators across a range of disease areas including oncology medicines [28, 39–44]. There have though been concerns with generic imatinib due to different polymorphic forms between the originator and generics as early small scale studies suggested differences [45]. However, later studies involving more patients showed no difference in outcomes between generics and originators of imatinib [45, 46], and, typically, no substantial evidence that generic imatinib is less effective than the originator [47].

In general, prices for generic medicines in Europe are 20% to 80% below originator prices; however, some generics can be priced as low as 2% to 4% of the originator price before the patent was lost [48, 49]. As a result, substantial differences can occur in the prices of generics across Europe [37, 50, 51]. Overall, low prices can potentially be achieved for generic cancer medicines because of the low cost of goods that have been reported at just 1% or more of originator prices for some new cancer medicines [52, 53]. These low cost of goods have already resulted in considerable discounts for generic imatinib across countries versus pre-patent loss prices [54, 55]. However, this is not universal. For instance, in China, generic imatinib is only 10%–20% below originator prices although generic capecitabine is 50% lower than originator prices [56]. There have also been low prices for generic versions of paclitaxel in Europe at just over 1% of originator prices [57]. Docetaxel also has a low price in some European markets enhanced by an appreciable number of generic versions available [26]. Having said this, changes in the manufacturer have resulted in the prices of some low volume old anticancer medicines rising appreciably among European countries including Italy and the UK [58]. However, pharmaceutical companies are now being fined for such behaviour, e.g. Euros 5.2 million for Aspen in Italy for price increases for some of its anticancer medicines, with ongoing investigations and initiatives across Europe to address this [59, 60].

In some European countries, there have also been issues regarding the prescribing of certain generic medicines where there are different indications, one of which is still patent protected. This was the case with pregabalin for the treatment of neuropathic pain as opposed to epilepsy [61].

There have also been concerns with drug shortages if the prices of medicines including generics become too low, which is already happening for certain parenteral medicines [62]. However, these concerns have to be balanced against the increasing availability and use of low-cost generic medicines to release resources to fund increased cancer care including new innovative medicines, reducing patient co-payments where these exist, and stimulating innovation [13, 48, 63–65].

Consequently, there is a need to document current regulations surrounding the pricing of generic oral anticancer medicines across Europe, and their impact on subsequent prices, as well as issues regarding prices of medicines once one indication loses its patent but not the others. As a result, the aims of this paper are multiple. The primary aim is to document current arrangements for the pricing of oral generic medicines across Europe and whether there are any differences in pricing policies for generic cancer medicines versus those for other disease areas. This is important to maximize savings following generics availability as we do see differences in reimbursement decisions for new medicines for cancer versus those for other disease areas [27, 66]. Secondly, to investigate what happens to the prices of oral cancer medicines if one indication loses its patent but not the other indication(s) since indication-specific pricing will undoubtedly reduce potential savings following generics availability, and, as mentioned, there were issues with the prescribing of pregabalin across indications when the first indication lost its patent [61]. Thirdly, to investigate how payers and their advisers envisage developments in the pricing of oral generic medicines for cancer as more cancer medicines lose their patents. Fourthly, to assess whether health authorities have any concerns with patient safety when prescribing oral generic cancer medicines similar to the situation with medicines with a narrow therapeutic index, such as lithium and certain medicines for epilepsy [67–69]. Fifthly, to review current prices for a number of oral cancer medicines across Europe where generic versions are available in all or some of the countries. This will also include an evaluation of prices over time to fully assess the impact of the different pricing arrangements for generic cancer medicines across Europe since we are aware that prices of generics can vary substantially across Europe due to different policies [26, 37, 48, 49], and that Central and Eastern European (CEE) countries are likely to have generics earlier [70]. Sixthly, to assess whether there are any differences in the prices of generics by population size and geography (CEE versus Western European countries) as there have been concerns that countries with small populations, and hence lower economies of scale, may have difficulty negotiating low prices for medicines [71] ; however, published literature has not found to be the case [31, 72]. Countries with greater economic power may potentially be able to negotiate lower prices for generics, and we will also investigate this. Lastly, as mentioned, prices of some old low volume anticancer medicines have risen among European countries in recent years with changes in the manufacturer [58], and we will assess the impact of any changes in manufacturers on subsequent prices, and the likely future direction.

We developed a number of hypotheses for the different aims. These include:

We believe that this is the first time that such comprehensive research regarding the regulations surrounding the pricing of oral cancer medicines, and their influence on subsequent prices, has been undertaken across Europe. Consequently, we believe the findings will inform future discussions within and between European and other countries regarding the pricing of oral generic cancer medicines now and into the future. In addition, we aim to stimulate discussions regarding subsequent prices and/or discounts for still patented oral cancer medicines that used off-patented products as their comparator during pricing negotiations. As a result, help with issues of affordability and sustainability of medicine use in the future in this high priority disease area.

When we refer to ‘generics’, we mean the chemical entity (INN). This study also includes imatinib, a comparatively newer anticancer agent, which is treated similarly to other oral generic cancer medicines. Biosimilars of originator biological medicines are regulated by a different framework, and incentives to increase their use are different [73]. Consequently, we will not be discussing biosimilars.

We have chosen to concentrate on Europe in view of the high use of generic medicines in this region. There are also different approaches to the pricing of generics among the various countries, as well as an appreciable number of existing initiatives to enhance the prescribing of generic medicines.

A mixed method approach was employed including both qualitative and quantitative research to meet the study objectives, and included 25 European countries, see Box 1.

This appreciable number of European countries fully encompasses differences in geography, population size, gross domestic product (GDP) per capita, pricing approaches towards generics as well as different approaches to the financing of healthcare [30, 70, 74]. Countries were also broken down into CEE and Western European countries based on the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) definition [75] to ascertain any differences in the pricing of oral generic cancer medicines based on population sizes and market power.

Qualitative interviews were undertaken with senior personnel within health authorities including heads of pricing and reimbursement of medicines as well as their advisers and a limited number of academics with expertise on national pharmaceutical issues and other key issues among European countries. The involvement of these senior level personnel in the qualitative interviews, and their involvement as co-authors, is seen as very important to enhance the accuracy, robustness and insight of the replies as there have been concerns when such approaches are not used [76, 77]. The co-authors were either identified via the Piperska group [78, 79] – a multidisciplinary network of professionals with interest in the quality use of medicines – or had been previous co-authors on similar pan-European projects involving generic medicinal products [29, 80–82]. We have successfully used this approach in other key areas [30, 61, 70, 73, 74, 80, 81, 83].

The qualitative questions to address the identified objectives included:

If applicable, pricing policies for generics were broken down into three principal groups to aid comparisons. This builds on previous publications that have used this approach [84–87], and include:

Health authority and health insurance company databases were used for the quantitative research apart from Greece and Serbia where commercial sources were used. The information within these databases is robust as they are typically used to trigger payment to pharmacists. In addition, the databases are regularly audited, and cover the whole country rather than a sample of pharmacies as seen with commercial databases. We have used this approach before when conducting research on prices and utilization of generics, originators and patented products within a class or related class [30, 49, 70, 72, 80–82, 88].

The oral cancer medicines selected for the quantitative research were busulfan (L01AB01), capecitabine (L01BC06), chlorambucil (L01AA02), cyclophosphamide (L01AA01), flutamide (L02BB01), imatinib (L01XE01), melphalan (L01AA03), methotrexate (L01BA01), and temozolomide (L01AX03) [89]. These oral cancer medicines were chosen to provide a range of medicines for use across different cancer types, with typically multiple indications, covering the oral cancer medicines listed in the World Health Organization (WHO) essential medicines list, and exhibiting varying timings regarding the loss of patent, building on previous publications [55]. Oral medicines, such as gefitinib, sorafenib, sunitinib and tioguanine were not included as there appeared to be no generics yet available for these oral cancer medicines even among the selected CEE countries at the time of the study. The (non-) tyrosine kinase inhibitors are a particular case as there are typically multiple indications as well as potentially different dates for patent loss across countries [90].

Since the perspective of this study is that of health authorities, reimbursed prices were principally chosen for comparative purposes rather than total prices, which include patient co-payments. Reimbursed prices can include prices after deducting legally mandated discounts; however, this is unlikely for generic medicines. In a minority of countries, e.g. Kosovo, procured and total prices were used as reimbursed prices were unavailable. In Italy and Norway, reimbursed prices were also listed but the medicines are typically dispensed in hospitals where further confidential discounts are provided. However, since these discounts are confidential, we could only report ambulatory care prices. Furthermore, in some countries, prices did not include VAT and/or pharmacy margins, e.g. Malta, The Netherlands and the Republic of Srpska. However, this was not seen to have an appreciable impact on the analyses since percentage reductions were typically used for comparative purposes to assess the influence of different policies. In addition, the prices of generics at least initially in a number of European countries are based on percentage reductions from pre-patent loss originator prices [30, 70]. We have successfully used this approach in a number of previous publications [30, 70, 74, 80, 84].

We are conscious that we used prices from Scotland rather than the UK as a whole. However, there are no differences in prices across the UK with reimbursed prices in ambulatory care based on the tariff price coupled with free-market competition, which leads to further price reductions over time. Similarly, no differences are envisaged in generic and originator drug prices in ambulatory care in Catalonia versus Spain as a whole. However, we acknowledge that there will be differences in hospital prices across Spain through variations in discounts and managed entry agreements between the different regions [91].

Prices were collected over a period of time between 2013 and 2017, based on the unit, e.g. tablet strength, for the different originators and the cheapest generics substitute unit available, especially for branded generics, as opposed to defined daily doses (DDDs). Unit strength was chosen as generally there are no DDDs for oral cancer medicines in view of typically a number of indications for each molecule [89]. The documented prices for each year between 2013 and 2017 were the last available price for that year, e.g. October to December if prices are adjusted every three months or December if prices are adjusted monthly. The years were chosen to assess the extent of any price changes in recent years especially given recent price increases for some off-patent medicines.

The actual unit strength chosen for comparative purposes reflects the most used strength in a number of European countries, although we recognize that there may be different strengths available in some countries. In addition:

Initially, prices were documented in the country’s currency if this was not Euros. Subsequently where relevant, prices were converted to Euros for the purposes of comparison based on current exchange rates and validated with the co-authors to enhance the robustness of the findings, see Table 1A in the Appendix.

Table 2A in the Appendix contains details of the population sizes and the breakdown of countries into three groups for analysis purposes (small, medium and large). Countries with populations under three million were described as small, those with populations between three and 16 million as medium, and the remainder as large to produce three roughly equal groups although recognizing that more countries were in the ‘small’ category than in the others.

Statistical tests were performed to ascertain any trends in prices across countries as well as any difference in price reductions over time as a result of the different approaches towards the pricing of generics across Europe. The significance threshold was set at p > 0.05. Statistical tests were also run to check whether prices were influenced by population size as this has been a concern in the past. However, we did not have enough variables to perform any multivariate analyses as there are not enough specific measures in each European country that had been initiated to control the price of generic cancer medicines which could be used as a yes/no variable. We have though collated the impact of the different pricing approaches for generic medicines across Europe as one of the principal objectives of this paper was to document these and their influence on subsequent prices for oral generic cancer medicines.

No analysis was made regarding the impact of volumes on generic drug prices as seen in other studies because this was not a focus of the paper [92]. This will be followed up in future studies. Potential savings from the increased utilization of generic medicines for cancer over time will also form a separate project building on previous calculations [93].

In line with the objectives of this paper, we will first report the findings from the qualitative research. This will be followed by the findings from the quantitative research.

Regulations surrounding the pricing of generics including those for cancer across Europe

Regulations for the pricing of generics generally and for oral cancer medicines including likely changes in the short term

As previously seen, there were differences in the approaches to the pricing of generics among the various European countries, see Table 1, which could again be categorized under three broad headings. These are: (i) prescriptive pricing approaches; (ii) market forces, and (iii) and a mixture of the approaches.

As shown in Table 1, there were no differences in the pricing approaches for generic oral medicines for oncology compared with those for other disease areas, see Table 1, apart from the fact that in some countries these cancer medicines were dispensed in hospitals, which could include additional discounts that are typically confidential. This is important given the considerable savings that can be achieved with the introduction of generics, see Table 2.

Pricing of oral cancer medicines if one indication has lost its patent

There were generally no issues with the pricing and usage of oral generic cancer medicines once one indication had lost its patent but not the other indication(s), see Table 1; however, this was not universal. There is similar to the situation in Germany once the first indication for a multiple-sourced product has lost its patent [61], i.e. the generic medicine can be prescribed across all indications at the discounted price versus the originator. However, this is different to the situation that existed with pregabalin among a number of European countries where the generics could only be prescribed for epilepsy and the originator must be prescribed and reimbursed accordingly for neuropathic pain [61].

This situation is encouraging for maximiẕing savings following generic drug availability given the considerable savings that can be achieved with the introduction of generics, see Table 2, and will be closely monitored in the future. This includes procured medicines for distribution in hospitals.

Substitution of oral cancer medicines and initiatives to encourage their prescribing

It was also encouraging to see that once generics became available, there were no concerns with substitution with the selected oral generic cancer medicines, see Table 1. This is similar to the general situation for cancer medicines [28]. Consequently, originators can be substituted with generics without compromising care. This is again important for maximizing savings once generics become available.

Initiatives to encourage the prescribing of generics in preference to originator cancer medicines among the various European countries, see Box 2, were similar to those for generic medicines in general.

Price reductions with generics over time and with originators, as well as the influence of population size and market forces

Prices for originator 400 mg imatinib were similar in Western European countries in 2015 before generic drug availability, see Figure 1. Generic imatinib was already available in CEE countries, e.g. in Albania, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Romania, Serbia and Slovakia, on or before 2013, and in Poland and Slovenia in 2014. Generic capecitabine and flutamide were already available in a number of Western European countries in 2013. The other three oral anticancer medicines were already available as generics among Western European countries before 2013.

As expected, there were differences in the prices of the generics for capecitabine (500 mg), flutamide (250 mg), imatinib (400 mg) and temozolomide (20 mg and 250 mg) in 2017 among the European countries where these generics were available, see Table 3, reflecting differences in the approaches to the pricing of oral generics among the various European countries, see Table 1.

There were no differences in the prices of capecitabine (500 mg), flutamide (250 mg), imatinib (400 mg) and temozolomide (20 mg and 250 mg) when the countries were broken down into small, medium or large populations, see Table 2A, apart from generic imatinib for European countries with large populations, i.e. capecitabine (p = 0.372 for medium and p = 0.100 for large), flutamide (p = 0.700 for medium and 0.385 for large), imatinib (p = 0.249 for medium and p = 0.037 for large), temozolomide 20 mg (p = 0.764 for medium and p = 0.085 for large) and temozolomide 250 mg (p = 0.951 for medium and p = 0.105 for large). Prices for generic capecitabine (p = 0.007), generic imatinib (p = 0.015) and temozolomide 20 mg (p = 0.015) were though typically appreciably higher when combined among Western European countries compared with CEE countries. However, this was not the case for flutamide 250 mg or temozolomide 250 mg. This will change for generic imatinib as prices fall among the large Western European countries over time, e.g. generic imatinib in Scotland by March 2018 was already 89.1% below pre-patent loss prices having only been made available in 2016.

Overall in 2017, the differences in the prices of generics of capecitabine (500 mg), flutamide (250 mg), imatinib (400 mg) and temozolomide (20 mg and 250 mg) among the different European countries, see Table 3, appear to be a reflection of the differences in the country’s pricing approaches towards generics, see Table 1, rather than population size when broken down into small, medium or large, as well as the timing of generic drug availability. These findings are similar to those with generic busulfan, chlorambucil, cyclophosphamide and melphalan, see Table 4, and confirm this trend certainly for oral generic cancer medicines.

There also appears to be no correlation in terms of the price reductions seen for generic capecitabine, flutamide, imatinib or temozolomide in 2017 versus 2013 originator prices with population sizes, i.e. appreciable price reductions over time were not confined to European countries with higher populations, see Table 2. There was also no significant difference in the percentage reduction between Western and CEE countries for capecitabine, flutamide, imatinib or temozolomide.

If anything, there was a greater reduction in the prices of generic capecitabine, see Figure 2, in countries with a mixed approach to the pricing of generics versus those with market forces (p = 0.035) and prescriptive (p = 0.041) approaches.

This was not the case for generic imatinib, see Figure 3, although there was a trend (p = 0.079 for market forces and p = 0.119 for prescriptive pricing approaches). However, this may change as prices of generic imatinib fall in The Netherlands, Spain, Sweden and the UK, e.g. as mentioned generic imatinib in Scotland was already 89.1% below pre-patent loss prices by March 2018 having only been made available in 2016.

Price changes for generics with changes in the licence holder

In recent years, the generic drug manufacturer Aspen has taken over the licence of busulfan, chlorambucil, and melphalan and enjoyed market monopoly, with typically no generics competition, despite the loss of patent protection. Another pharmaceutical company, Baxter, has used a similar strategy with cyclophosphamide. Countries have typically been faced with having to either accept these higher prices or no longer procuring and/or reimbursing these medicines.

Figure 4 depicts current prices per tablet for these four oral generic anticancer medicines (2017) where these are currently listed and reimbursed since not all European countries currently reimburse these four medicines. There were no significant differences in the mean prices for these four anticancer medicines between Western and CEE countries. In the case of busulfan, there was a difference in current prices among European countries, with Western European countries typically having higher prices but this did not reach significance (p = 0.08). Population size again did not appear to influence subsequent prices.

There were appreciable price rises in a number of other European countries following Aspen’s purchase of busulfan, chlorambucil and melphalan from GlaxoSmithKline, see Table 4.

Similar price rises were seen in Germany during this period, for example:

Overall there again appears to be no link between prices, geographic region and population size for these four medicines despite previous concerns. If anything, countries with smaller populations, such as Estonia had lower prices than Belgium, Italy and the UK. This appears to be in contrast with previous publications [71], although this is in accordance with previous findings in Lithuania and the Republic of Srpska [31, 72].

The difference in prices of these four molecules between the countries in 2017 may well reflect differences in negotiations when the new company took over the molecules and relaunched them as a new originator at a higher price. Countries such as Estonia appeared successful in negotiating lower price increases for the relaunched medicines versus for instance Belgium, Italy and the UK. However, as mentioned earlier, the company was subsequently fined Euros 5.2 million in Italy for their activities [59]. Currently, Germany has a moratorium law stating that for any price increase, there will be an increase in the mandatory rebate of exactly the same amount as the increase. Effectively, this means that the price paid by statutory heathcare funds for ambulatory care medicines does not change [114, 115]. Legislation is also being introduced in the UK to reduce the price of generic medicines where competition fails to reduce prices and companies are seen to charge the National Health Service (NHS) unreasonably high prices [113]. The Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) in the UK has also provisionally found that two companies broke the law by agreeing not to compete to supply generic hydrocortisone to the NHS driving up annual costs by two million GBP [116]. There are also ongoing deliberations in Europe regarding concerns with appreciable price increases for generics and whether this breaks EU competition rules [60, 117]. In addition, we may see countries combining to form regional co-operations between Member States to further reduce prices where there are concerns with unjustified price rises building on current consortia [118–120]. However, this has to be balanced against issues of future profitability and potential drug shortages with for instance only 75 melphalan tablets dispensed in ambulatory care in Scotland during the study period (SM personal communication), and with just 11 boxes of generic melphalan dispensed in Serbia in 2015.

We believe this is the first study to comprehensively research the situation regarding the pricing of oral generic cancer medicines in this high priority disease area. We believe our findings again highlight the differences that are seen in the various approaches to the pricing of generics across Europe, see Table 1, and their subsequent influence on the prices of generics and discounts obtained. These considerable differences are in direct contrast with the more limited differences in prices for on-patent medicines across Europe, especially high cost ones [121], although these can still be considerable [122].

Prices for generic capecitabine, imatinib, and temozolomide 20 mg, were significantly higher when combined among Western European countries as compared with CEE countries. This may reflect greater availability of resources to spend on medicines among Western countries. However, this is not universal as there were no differences in prices between Western European and CEE countries for flutamide 250 mg or temozolomide 250 mg. Alternatively, generics may be available earlier in CEE countries with associated earlier falls in their price as seen with imatinib. As mentioned, generic imatinib in Scotland was already 89.1% below pre-patent loss prices in March 2018 having only been made available in 2016, see Figure 1. Having said this, there were already some appreciable price reductions for these various molecules and strengths among Western European countries comparing generic drug prices in 2017 versus originator prices in 2013, Table 3 and Figure 3. In addition, no overall difference in the price reductions for these molecules and strengths was found for Western European countries combined versus CEE countries combined.

The picture regarding methotrexate is complicated by the use of this medicine for immunological conditions, such as rheumatoid arthritis and psoriasis. This meant that different originator and tablet strengths (2.5 mg or 5 mg) were available amongst the European countries making comparisons difficult. In addition, the considerable time that both the originator and generic methotrexate have been available across Europe meant there were limited price reductions in reality between 2017 compared with 2013 among the various European countries. Consequently, no detailed analysis was undertaken with methotrexate.

The price reductions for capecitabine, flutamide, imatinib and temozolomide that have been achieved in practice, see Table 3, confirm the findings of Hill et al. that the costs of goods for cancer medicines can be very low in reality [52, 53]. This fuels the debate for greater transparency in the pricing of new medicines for cancer when pharmaceutical companies request premium prices especially where there is limited health gain for their new cancer medicines versus current standards.

In view of our findings, we also believe European health authorities, as well as health authorities from other countries, can use these results to reassess their pricing approaches for generics, and the subsequent implications for oral generic cancer medicines, given concerns with the increasing costs of medicines to treat patients with cancer and issues of sustainability [3, 9, 28]. This is already happening, and may well accelerate, especially if issues of access and sustainability of cancer care continue to be priority issues for all key stakeholder groups. For instance, Austria, Lithuania, and Sweden, have recently introduced measures to further lower the prices they pay for generics and this trend is likely to continue, see Table 1. However, this has to be balanced against issues of parallel exports and associated drug shortages if the prices of generics become too low [37, 123], which is depicted in the unavailability of some oral generic cancer medicines in the countries studied. This will be the subject of ongoing research.

Based on our findings combined with the continual pressure on oncology budgets, we would also likely to see countries increasingly reassess the prices of on-patent cancer medicines in their country once the comparator medicine used for pricing and reimbursement negotiations loses its patent [124]. Such activities will be enhanced by the low prices that have been achieved for oral cancer medicines once their patent is lost, see Tables 2 and 3, which will continue.

Encouragingly, we saw no differences in the pricing approaches for generic cancer medicines versus those for other disease areas despite the emotive nature of cancer, and this will continue. This is essential to maximize savings from the availability of generic cancer medicines once available, with ongoing initiatives across Europe to encourage their use where pertinent. Likely, current and future initiatives to enhance the prescribing of oral generic cancer medicines include additional demand-side measures especially among European countries with currently low use of generics versus originators. This could be alongside continued educational initiatives among key stakeholder groups, including patients, where pertinent about the lack of problems with oral generic cancer medicines given there were no concerns with substitution among the European countries surveyed, see Table 1.

We are also unlikely to see major changes in pricing approaches once one indication loses its patent. The situation seen in Germany, as well as initiatives to encourage INN prescribing, helps in this regard. These initiatives are essential in oncology given the growing burden of the cost of medicines to treat patients with cancer across Europe combined with the need to continue to provide universal healthcare. Encouraging greater prescribing of generic medicines will be helped by limited or no fears with substituting generic cancer medicines for originators among physicians and pharmacists. This is unlike a limited number of other disease areas including some medicines for patients with epilepsy as well as lithium for patients with certain mental health conditions [67–69].

If companies continue to purchase the patent for old cancer medicines and other products, and relaunch them at considerably higher prices, there is likely to be co-ordinated activities across Europe to try and address this. We are already seeing companies being fined, e.g. Italy, as well as countries instigating measures to reduce any burden from such approaches as seen currently in Germany and the UK. Such punitive actions are likely to grow in the future if this trend continues. However, this has to be balanced against potential availability especially if only small volumes are being used. This will again be the subject of continuing research.

We have again seen appreciable differences in the regulations surrounding the pricing of generics across Europe, reflected in different reimbursed prices for oral generic cancer medicines. Welcomed from an equity and resource perspective were no differences in the pricing approaches for medicines for cancer as opposed to other disease areas to help maximize savings once generics become available. In addition, the prices of generics, and any difference in the prices of generics in 2017, or price reductions versus 2013 originator prices, did not appear to be influenced by population size. This is also encouraging to maximize savings from the availability of oral generic cancer medicines. The prices of some generics were higher among Western European countries in 2017; however, this could have been influenced by generics being available earlier among CEE countries. There are concerns with some off-patented medicines being relaunched by alternative companies at appreciably higher prices, although there are ongoing steps across Europe to try to address this. These initiatives are likely to grow if this trend continues.

Reassuringly, there are no concerns with substitution of oral generic medicines. In addition, prices were typically similar across indications. Both results are important to maximiẕe savings from generic drug availability once at least one indication loses its patent.

We have tried to reduce limitations with this study by using senior level personnel for the qualitative research as well as health authority and health insurance company databases for the quantitative research. However, we are aware that we did not use reimbursed prices throughout the countries, some prices did not include VAT, and we cannot be sure that the medicines chosen for the research are entirely used for cancer indications. Despite these concerns, we believe the findings of our comprehensive research are robust providing direction not only to key stakeholder groups across Europe but also wider.

There was no funding for this research and no assistance with the write-up.

Competing interests: Most of the authors work directly for health authorities or health insurance companies or are advisers to them. Professor Steven Simoens has previously held the EGA Chair ‘European policy towards generic medicines’. All the authors have no other conflicts of interest to declare.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

1Strathclyde Institute of Pharmacy and Biomedical Sciences, University of Strathclyde, Glasgow G4 0RE, UK

2Health Economics Centre, University of Liverpool Management School, Liverpool, UK

3Division of Clinical Pharmacology, Karolinska Institute, Karolinska University Hospital Huddinge, SE-141 86, Stockholm, Sweden

4School of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Universiti Sains Malaysia, Penang, Malaysia

5Institute of Translational Medicine, University of Liverpool, UK

6KU Leuven Department of Pharmaceutical and Pharmacological Sciences, Leuven, Belgium

7Department of Pharmacology, College of Pharmacy, Hawler Medical University, Erbil, Iraq

8Department of Pathology, Forensic Medicine and Pharmacology, Institute of Biomedical Sciences, Faculty of Medicine, Vilnius University, Vilnius, Lithuania

9HCD Economics, The Innovation Centre, Daresbury, WA4 4FS, UK

10NHS Lothian, Edinburgh, UK

11Independent researcher, Boston, MA, USA

12Independent consumer advocate, 11a Lydia Street, Brunswick, Victoria 3056, Australia

13Department of Drug Management, Faculty of Health Sciences, Jagiellonian University Medical College, Krakow, Poland

14Department of Pharmacy, Faculty of Medicine, University of Medicine, Tirana, Albania

15University of Medicine, Tirana, Albania

16Main Association of Austrian Social Security Institutions, Department of Pharmaceutical Affairs, 1 Haidingergasse, AT-1030 Vienna, Austria

17Statistics Department, APB, 11 Rue Archimède, BE-1000 Bruxelles, Belgium

18Faculty of Pharmacy, Department of Social Pharmacy and Pharmacoeconomics, Medical University of Sofia, Sofia, Bulgaria

19State Agency of Medicines, 1 Nooruse, EE-50411 Tartu, Estonia

20IRDES, 117 bis rue Manin, FR-75019 Paris, France

21Wissenschaftliches Institut der AOK (WidO), 31 Rosenthaler Straße, DE-10178 Berlin, Germany

22School of Economics and Political Science, University of Athens, Athens

23Pharmaceutical Drug Department, Azienda Sanitaria Locale of Verona, Verona, Italy

24UBT – Higher Education Institute Prishtina, Kosovo

25Institute of Public Health & Faculty of Pharmacy, Riga Stradins University, Latvia

26Department of Pharmacy, Ministry of Health of the Republic of Lithuania, Vilnius, Lithuania

27National Health Care Institute (ZIN), 4 Eekholt, NL-1112 XH Diemen, The Netherlands

28HTA and Reimbursement, Norwegian Medicines Agency, Oslo, Norway

29HTA Consulting, 17/3 Starowis′lna Str, PL-31-038 Cracow, Poland

30Ministry of Health and Social Welfare, Banja Luka, Republic of Srpska, Bosnia and Herzegovina

31University of Banja Luka, Faculty of Medicine, Department of Social Pharmacy, Banja Luka, Republic of Srpska, Bosnia and Herzegovina

32Health Insurance Fund of Republika Srpska, 8 Zdrave Korde, 78000 Banja Luka, Republic of Srpska, Bosnia and Herzegovina

33Agency for medicines and medical devices of Bosnia and Herzegovina, Veljka Mladjenovica bb, 78000 Banja Luka, Bosnia and Herzegovina

34Faculty of Medicine, Public Health and Management Department, ‘Carol Davila’ University of Medicine and Pharmacy Bucharest, RO-050463 Bucharest, Romania

35ZEM Solutions, 9 Mosorska, RS-11 000 Belgrade, Serbia

36Health Insurance Institute, 24 Miklosiceva, SI-1507 Ljubljana, Slovenia

37Faculty of Medicine, Slovak Medical University in Bratislava, Bratislava, Slovakia

38591 Gran Via de les Corts Catalanes, 4a place, ES-08007 Barcelona, Spain

39Stockholm County Council, Stockholm, Sweden

40TLV (Dental and Pharmaceutical Benefits Agency), 18 Fleminggatan, SE-10422, Stockholm, Sweden

41NHS National Services Scotland, Gyle Square, 1 South Gyle Crescent, Edinburgh EH12 9EB, UK

References

1. Kelly RJ, Smith TJ. Delivering maximum clinical benefit at an affordable price: engaging stakeholders in cancer care. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15(3):e112-8.

2. Howard DH, Bach PB, Berndt ER, Conti RM. Pricing in the market for anticancer drugs. J Econ Perspect. 2015;29(1):139-62.

3. Godman B, Wild C, Haycox A. Patent expiry and costs for anticancer medicines for clinical use. Generics and Biosimilars Initiative Journal (GaBI Journal). 2017;6(3):105-6. doi:10.5639/gabij.2017.0603.021

4. Prasad V, Wang R, Afifi SH, Mailankody S. The rising price of cancer drugs-a new old problem? JAMA Oncol. 2016. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.4275. [Epub ahead of print]

5. Kantarjian HM, Fojo T, Mathisen M, Zwelling LA. Cancer drugs in the United States: Justum Pretium–the just price. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(28):3600-4.

6. Cohen D. Cancer drugs: high price, uncertain value. BMJ. 2017;359:j4543.

7. Grössmann N, Wild C. Between January 2009 and April 2016, 134 novel anticancer therapies were approved: what is the level of knowledge concerning the clinical benefit at the time of approval? ESMO Open. 2017;1(6):e000125. doi:10.1136/esmoopen-2016-000125.

8. Bach PB, Saltz LB. Raising the dose and raising the cost: the case of pembrolizumab in lung cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2017;109(11).

9. Godman B, Oortwijn W, de Waure C, Mosca I, Puggina A, Specchia ML, et al. Links between pharmaceutical R&D models and access to affordable medicines. A study for the ENVI Committee.

10. Dusetzina SB. Drug pricing trends for orally administered anticancer medications reimbursed by commercial health plans, 2000-2014. JAMA Oncol. 2016;2(7):960-1.

11. Gordon N, Stemmer SM, Greenberg D, Goldstein DA. Trajectories of injectable cancer drug costs after launch in the United States. Journal of clinical oncology. 2017:Jco2016722124.

12. Gyawali B, Sullivan R. Economics of cancer medicines: for whose benefit? New Bioeth. 2017;23(1):95-104.

13. Chalkidou K, Marquez P, Dhillon PK, Teerawattananon Y, Anothaisintawee T, Gadelha CA, et al. Evidence-informed frameworks for cost-effective cancer care and prevention in low, middle, and high-income countries. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15(3):e119-31.

14. Wilking N, Lopes G, Meier K, Simoens S, van Harten W, Vulto AG. Can we continue to afford access to cancer treatment? Eur Oncol Haematol. 2017;13(2):114-9.

15. Lindsley CW. New 2016 data and statistics for global pharmaceutical products and projections through 2017. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2017;8(8):1635-6.

16. Allied Market Research. Oncology/cancer drugs market by therapeutic modalities (chemotherapy, targeted therapy, immunotherapy, hormonal), cancer types (blood, breast, gastrointestinal, prostate, skin, respiratory/lung cancer) – global opportunity analysis and industry forecast, 2013-2020 [homepage on the Internet]. [cited 2019 Mar 14]. Available from: https://www.alliedmarketresearch.com/oncology-cancer-drugs-market?oncology-cancer-drugs-market

17. IMSH Institute for Healthcare Informatics. Global Oncology Trend Report. A review of 2015 and outlook to 2020. June 2016. Available from: https://www.scribd.com/document/323179495/IMSH-Institute-Global-Oncology-Trend-2015-2020-Report

18. Simoens S, van Harten W, Lopes G, Vulto A, Meier K, Wilking N. What Happens when the cost of cancer care becomes unsustainable. Eur Oncol Haematol. 2017;13(2):108-13.

19. Tefferi A, Kantarjian H, Rajkumar SV, Baker LH, Abkowitz JL, Adamson JW, et al. In support of a patient-driven initiative and petition to lower the high price of cancer drugs. Mayo Clin Proc. 2015;90(8):996-1000.

20. Sarwar MR, Iftikhar S, Saqib A. Availability of anticancer medicines in public and private sectors, and their affordability by low, middle and high-income class patients in Pakistan. BMC Cancer. 2018;18(1):14.

21. Atieno OM, Opanga S, Martin A, Kurdi A, Godman B. Pilot study assessing the direct medical cost of treating patients with cancer in Kenya; findings and implications for the future. J Med Econ. 2018;21(9):878-87.

22. Jakupi A, Godman B, Martin A, Haycox A, Baholli I. Utilization and expenditure of anti-cancer medicines in Kosovo: findings and implications. Pharmacoecon Open. 2018;2(4):423-32.

23. Ghinea H, Kerridge I, Lipworth W. If we don’t talk about value, cancer drugs will become terminal for health systems. The Conversation. 2015 Jul 26.

24. Prasad V, De Jesus K, Mailankody S. The high price of anticancer drugs: origins, implications, barriers, solutions. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2017;14(6):381-90.

25. Goldstein DA, Clark J, Tu Y, Zhang J, Fang F, Goldstein R, et al. A global comparison of the cost of patented cancer drugs in relation to global differences in wealth. Oncotarget. 2017;8(42):71548-55.

26. World Health Organization. Hoen E’t. Access to cancer treatment: a study of medicine pricing issues with recommendations for improving access to cancer medication [homepage on the Internet]. [cited 2019 Mar 14]. Available from: http://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/documents/s21758en/s21758en.pdf

27. Haycox A. Why cancer? Pharmacoecon. 2016;34(7):625-7.

28. Yang YT, Nagai S, Chen BK, Qureshi ZP, Lebby AA, Kessler S, et al. Generic oncology drugs: are they all safe? Lancet Oncol. 2016;17(11):e493-e501.

29. Godman B, Wettermark B, van Woerkom M, Fraeyman J, Alvarez-Madrazo S, Berg C, et al. Multiple policies to enhance prescribing efficiency for established medicines in Europe with a particular focus on demand-side measures: findings and future implications. Front Pharmacol. 2014;5:106.

30. Godman B, Shrank W, Andersen M, Berg C, Bishop I, Burkhardt T, et al. Comparing policies to enhance prescribing efficiency in Europe through increasing generic utilization: changes seen and global implications. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2010;10(6):707-22.

31. Garuoliene K, Godman B, Gulbinovic J, Wettermark B, Haycox A. European countries with small populations can obtain low prices for drugs: Lithuania as a case history. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2011;11(3):343-9.

32. Dylst P, Vulto A, Simoens S. Demand-side policies to encourage the use of generic medicines: an overview. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2013;13(1):59-72.

33. Dylst P, Vulto A, Godman B, Simoens S. Generic medicines: solutions for a sustainable drug market? Appl Health Econ Health Pol. 2013;11(5):437-43.

34. Babar ZU, Kan SW, Scahill S. Interventions promoting the acceptance and uptake of generic medicines: a narrative review of the literature. Health Policy. 2014;117(3):285-96.

35. Moe-Byrne T, Chambers D, Harden M, McDaid C. Behaviour change interventions to promote prescribing of generic drugs: a rapid evidence synthesis and systematic review. BMJ Open. 2014;4(5):e004623.

36. Kaplan WA, Ritz LS, Vitello M, Wirtz VJ. Policies to promote use of generic medicines in low and middle income countries: a review of published literature, 2000-2010. Health Policy. 2012;106(3):211-24.

37. Wouters OJ, Kanavos P, McKEE M. Comparing generic drug markets in Europe and the United States: prices, volumes, and spending. Milbank Q. 2017;95(3):554-601.

38. Bucek Psenkova M, Visnansky M, Mackovicova S, Tomek D. Drug policy in Slovakia. Value Health Reg Issues. 2017;13:44-9.

39. Kesselheim AS, Misono AS, Lee JL, Stedman MR, Brookhart MA, Choudhry NK, et al. Clinical equivalence of generic and brand-name drugs used in cardiovascular disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2008;300(21):2514-26.

40. Lessing C, Ashton T, Davis PB. The impact on health outcome measures of switching to generic medicines consequent to reference pricing: the case of olanzapine in New Zealand. J Prim Health Care. 2015;7(2):94-101.

41. Veronin M. Should we have concerns with generic versus brand antimicrobial drugs? A review of issues. JPHSR. 2011;2:135-50.

42. Paton C. Generic clozapine: outcomes after switching formulations. Br J Psychiatry. 2006;189:184-5.

43. Corrao G, Soranna D, Arfe A, Casula M, Tragni E, Merlino L, et al. Are generic and brand-name statins clinically equivalent? Evidence from a real data-base. Eur J Internal Med. 2014;25(8):745-50.

44. Corrao G, Soranna D, Merlino L, Mancia G. Similarity between generic and brand-name antihypertensive drugs for primary prevention of cardiovascular disease: evidence from a large population-based study. Eur J Clin Invest. 2014;44(10):933-9.

45. Mathews V. Generic imatinib: the real-deal or just a deal? Leuk Lymphoma. 2014;55(12):2678-80.

46. Malhotra H, Sharma P, Bhargava S, Rathore OS, Malhotra B, Kumar M. Correlation of plasma trough levels of imatinib with molecular response in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia. Leuk Lymphoma. 2014;55(11):2614-9.

47. Canadian Association of Pharmacy in Oncology. de Lemos M, Kletas V. Generic imatinib: review of the literature on clinical efficacy [homepage on the Internet]. [cited 2019 Mar 14]. Available from: http://www.capho.org/sites/default/files/nops/Generic%20Imatinib%20Review%20of%20the%20Literature%20on%20Clinical%20Efficacy%20-%20Mario%20de%20 Lemos.pdf

48. Dylst P, Vulto A, Simoens S. Societal value of generic medicines beyond cost-saving through reduced prices. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2015;15(4):701-11.

49. Woerkom M, Piepenbrink H, Godman B, Metz J, Campbell S, Bennie M, et al. Ongoing measures to enhance the efficiency of prescribing of proton pump inhibitors and statins in The Netherlands: influence and future implications. J Comp Eff Res. 2012;1(6):527-38.

50. Simoens S. International comparison of generic medicine prices. Curr Med Res Opin. 2007;23(11):2647-54.

51. Wouters OJ, Kanavos PG. A comparison of generic drug prices in seven European countries: a methodological analysis. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17(1):242.

52. Hill A, Gotham D, Fortunak J, Meldrum J, Erbacher I, Martin M, et al. Target prices for mass production of tyrosine kinase inhibitors for global cancer treatment. BMJ Open. 2016;6(1):e009586.

53. Hill A, Redd C, Gotham D, Erbacher I, Meldrum J, Harada R. Estimated generic prices of cancer medicines deemed cost-ineffective in England: a cost estimation analysis. BMJ Open. 2017;7(1):e011965.

54. Chen CT, Kesselheim AS. Journey of generic imatinib: a case study in oncology drug pricing. J Oncol Pract. 2017;13(6):352-5.

55. Barber M, Gotham D, Hill A. Potential price reductions for cancer medicines on the WHO Essential Medicines List [homepage on the Internet]. [cited 2019 Mar 14]. Available from: http://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/documents/s23154en/s23154en.pdf

56. Guan X, Tian Y, Ross-Degnan D, Man C, Shi L. Interrupted time-series analysis of the impact of generic market entry of antineoplastic products in China. BMJ Open. 2018;8(7):e022328.

57. Matusewicz W, Godman B, Pedersen HB, Furst J, Gulbinovic J, Mack A, et al. Improving the managed introduction of new medicines: sharing experiences to aid authorities across Europe. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2015;15(5):755-8.

58. Hawkes N. Drug company Aspen faces probe over hiking generic prices. BMJ. 2017;357:j2417.

59. Kahn T. Aspen loses Italy appeal over cancer drug prices. Business Day. 2017 Jun 15.

60. Pagliarulo N. EU investigating generic drugmaker over cancer drug price hikes. Biopharma Dive. 2017 May 15.

61. Godman B, Wilcock M, Martin A, Bryson S, Baumgärtel C, Bochenek T, de Bruyn M. Generic pregabalin; current situation and implications for health authorities, generics and biosimilars manufacturers in the future. Generics and Biosimilars Initiative Journal (GaBI Journal). 2015;4(3):125-35. doi:10.5639/gabij.2015.0403.028

62. McLaughlin M, Kotis D, Thomson K, Harrison M, Fennessy G, Postelnick M, et al. Empty shelves, full of frustration: consequences of drug shortages and the need for action. Hosp Pharm. 2013;48(8):617-8.

63. Putrik P, Ramiro S, Kvien TK, Sokka T, Pavlova M, Uhlig T, et al. Inequities in access to biologic and synthetic DMARDs across 46 European countries. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73(1):198-206.

64. Kosti M, Djakovic L, Šuji R, Godman B, Jankovi SM. Inflammatory Bowel Diseases (Crohn’s disease and Ulcerative Colitis): cost of treatment in Serbia and the implications. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2017;15(1):85-93.

65. Cameron A, Mantel-Teeuwisse AK, Leufkens HG, Laing RO. Switching from originator brand medicines to generic equivalents in selected developing countries: how much could be saved? Value Health. 2012;15(5):664-73.

66. Wild C, Grössmann N, Bonanno PV, Bucsics A, Furst J, Garuoliene K, et al. Utilisation of the ESMO-MCBS in practice of HTA. Ann Oncol. 2016;27(11):2134-6.

67. Duerden MG, Hughes DA. Generic and therapeutic substitutions in the UK: are they a good thing? Br Clin Pharmacol. 2010;70(3):335-41.

68. Ferner RE, Lenney W, Marriott JF. Controversy over generic substitution. BMJ. 2010;340:c2548.

69. Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency. Antiepileptic drugs: updated advice on switching between different manufacturers’ products. 2017 [homepage on the Internet]. [cited 2019 Mar 14]. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/drug-safety-update/antiepileptic-drugs-updated-advice-on-switching-between-different-manufacturers-products#chm-review-and-update

70. Godman B, Shrank W, Andersen M, Berg C, Bishop I, Burkhardt T, et al. Policies to enhance prescribing efficiency in Europe: findings and future implications. Front Pharmacol. 2010;1:141.

71. McKee M, Stuckler D, Martin-Moreno JM. Protecting health in hard times. BMJ. 2010;341:c5308.

72. Markovic-Pekovic V, Skrbic R, Godman B, Gustafsson LL. Ongoing initiatives in the Republic of Srpska to enhance prescribing efficiency: influence and future directions. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2012;12(5):661-71.

73. Moorkens E, Vulto AG, Huys I, Dylst P, Godman B, Keuerleber S, et al. Policies for biosimilar uptake in Europe: an overview. PloS One. 2017;12(12):e0190147.

74. Baumgärtel C, Godman B, Malmström R, Andersen M, Abuelkhair M, Abdu S, et al. What lessons can be learned from the launch of generic clopidogrel? Generics and Biosimilars Initiative Journal (GaBI Journal). 2012;1(2):58-68. doi:10.5639/gabij.2012.0102.016

75. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. OECD Glossary of statistical terms [homepage on the Internet]. [cited 2019 Mar 14]. Available from: http://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/docserver/download/3008121e.pdf?expires=1521443673&id=id&accname=guest&checksum=EDB68C374A8FE629D5A2C1FAFB0AEB6C

76. Coma A, Zara C, Godman B, Agusti A, Diogene E, Wettermark B, et al. Policies to enhance the efficiency of prescribing in the Spanish Catalan region: impact and future direction. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2009;9(6):569-81.

77. Kanavos P. Generic policies: rhetoric vs. reality. Euro Observer. 2008;10(2):1-6.

78. Piperska Group. Piperska 2017 [homepage on the Internet]. [cited 2019 Mar 14]. Available from: http://www.piperska.org/

79. Garattini S, Bertele V, Godman B, Haycox A, Wettermark B, Gustafsson LL. Enhancing the rational use of new medicines across European health care systems. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2008;64(12):1137-8.

80. Moon JC, Godman B, Petzold M, Alvarez-Madrazo S, Bennett K, Bishop I, et al. Different initiatives across Europe to enhance losartan utilization post generics: impact and implications. Front Pharmacol. 2014;5:219.

81. Godman B, Petzold M, Bennett K, Bennie M, Bucsics A, Finlayson AE, et al. Can authorities appreciably enhance the prescribing of oral generic risperidone to conserve resources? Findings from across Europe and their implications. BMC Med. 2014;12:98.

82. Vonina L, Strizrep T, Godman B, Bennie M, Bishop I, Campbell S, et al. Influence of demand-side measures to enhance renin-angiotensin prescribing efficiency in Europe: implications for the future. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2011;11(4):469-79.

83. Ferrario A, Arja D, Bochenek T, ati T, Dankó D, Dimitrova M, et al. The implementation of managed entry agreements in Central and Eastern Europe: findings and implications. Pharmacoecon. 2017;35(12):1271-85.

84. Godman B, Shrank W, Wettermark B, Andersen M, Bishop I, Burkhardt T, et al. Use of generics – a critical cost containment measure for all healthcare professionals in Europe? Pharmaceuticals. 2010;3(8):2470-94.

85. Godman B, Bucsics A, Burkhardt T, Piessnegger J, Schmitzer M, Barbui C, et al. Potential to enhance the prescribing of generic drugs in patients with mental health problems in Austria; implications for the future. Front Pharmacol. 2012;3:198.

86. Simoens S. A review of generic medicine pricing in Europe. Generics and Biosimilars Initiative Journal (GaBI Journal). 2012;1(1):8-12. doi:10.5639/gabij.2012.0101.004

87. Leopold C, Vogler S, Mantel-Teeuwisse AK, de Joncheere K, Leufkens HG, Laing R. Differences in external price referencing in Europe: a descriptive overview. Health Policy. 2012;104(1):50-60.

88. Leporowski A, Godman B, Kurdi A, MacBride-Stewart S, Ryan M, Hurding S, et al. Ongoing activities to optimize the quality and efficiency of lipid-lowering agents in the Scottish national health service: influence and implications. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2018;18(6):655-66.

89. WHO Collaborating Centre for Drug Statistics Methodology. ATC/DDD Index [homepage on the Internet]. [cited 2019 Mar 14]. Available from: https://www.whocc.no/

90. Venkatesan S, Lamfers M, Leenstra S, Vulto AG. Overview of the patent expiry of (non-) tyrosine kinase inhibitors approved for clinical use in the EU and the US. Generics and Biosimilars Initiative Journal (GaBI Journal). 2017;6(2):89-96. doi:10.5639/gabij.2017.0602.016

91. Clopes A, Gasol M, Cajal R, Segu L, Crespo R, Mora R, et al. Financial consequences of a payment-by-results scheme in Catalonia: gefitinib in advanced EGFR-mutation positive non-small-cell lung cancer. J Med Econ. 2017;20(1):1-7.

92. Dylst P, Simoens S. Does the market share of generic medicines influence the price level?: a European analysis. Pharmacoecon. 2011;29(10):875-82.

93. BBC News – Health. Cancer drugs price rise ‘costing NHS millions’. 2017 Jan 29.

94. Vella O. Further reductions in medicine prices. Times of Malta. 2017 Jan 15. Available from: https://www.timesofmalta.com/articles/view/20170115/consumer-affairs/Further-reductions-in-medicine-prices.636591

95. Petrova G. Pricing and reimbursement of medicines in Central and East European countries. J Pharmaceut Res Health Care. 2014;2(6);4311-28.

96. Kawalec P, Stawowczyk E, Tesar T, Skoupa J, Turcu-Stiolica A, Dimitrova M, et al. Pricing and reimbursement of biosimilars in Central and Eastern European countries. Front Pharmacol. 2017;8:288.

97. Baltic Statistics on Medicines 2010-2012 [homepage on the Internet]. [cited 2019 Mar 14]. Available from: http://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/documents/s21301en/s21301en.pdf

98. Marcheva M T-KL, Petrova G. Pricing and reimbursement of medicines in Central and East European countries. World Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences. 2013;2(6):4311-28.

99. WHO Collaborating Centre for Pharmaceutical Pricing and Reimbursement Policies. Festøy H, Aanes T, Ognøy AE. PPRI Pharma Profile Norway June 2015 [homepage on the Internet]. [cited 2019 Mar 14]. Available from: https://ppri.goeg.at/sites/ppri.goeg.at/files/inline-files/PPRI%20Norway%202018.pdf

100. Godman B, Sakshaug S, Berg C, Wettermark B, Haycox A. Combination of prescribing restrictions and policies to engineer low prices to reduce reimbursement costs. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2011;11(1):121-9.

101. Kalaba M, Godman B, Vuksanovi A, Bennie M, Malmström RE. Possible ways to enhance renin-angiotensin prescribing efficiency: Republic of Serbia as a case history? J Comp Eff Res. 2012;1(6):539-49.

102. Vogler S, Zimmermann N, Gombocz M, Mörtenhuber S, Skala R, Lichtenecker J, et al. Short PPRI Pharma Profile Austria. January 2018 [homepage on the Internet]. [cited 2019 Mar 14]. Available from: https://ppri.goeg.at/sites/ppri.goeg.at/files/inline-files/Short_PPRI_Pharma_Profile_AT_2017_final_neu_1.pdf

103. Bucsics A, Godman B, Burkhardt T, Schmitzer M, Malmström RE. Influence of lifting prescribing restrictions for losartan on subsequent sartan utilization patterns in Austria: implications for other countries. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2012;12(6):809-19.

104. Godman B, Abuelkhair M, Vitry A, Abdu S, Bennie M, Bishop I, et al. Payers endorse generics to enhance prescribing efficiency: impact and future implications, a case history approach. Generics and Biosimilars Initiative Journal (GaBI Journal). 2012;1(2):69-83. doi:10.5639/gabij.2012.0102.017

105. Pontén J, Rönnholm G, Skiöld P. PPRI Pharma Profile Sweden. April 2017 [homepage on the Internet]. [cited 2019 Mar 14]. Available from: https://ppri.goeg.at/sites/ppri.goeg.at/files/inline-files/PPRI_Pharma_Profile_Sweden_2017_5.pdf

106. Godman B, Persson M, Miranda J, Skiold P, Wettermark B, Barbui C, et al. Changes in the utilization of venlafaxine after the introduction of generics in Sweden. Appl Health Econ Health Pol. 2013;11(4):383-93.

107. GaBI Online – Generics and Biosimilars Initiative. The Greek problem of generics pricing [www.gabionline.net]. Mol, Belgium: Pro Pharma Communications International; [cited 2019 Mar 14]. Available from: www.gabionline.net/Generics/Research/The-Greek-problem-of-generics-pricing.

108. Vogler S. The impact of pharmaceutical pricing and reimbursement policies on generics uptake: implementation of policy options on generics in 29 European countries–an overview. Generics and Biosimilar Journal. 2012;1(2):93-100. doi:10.5639/gabij.2012.0102.020

109. Dylst P, Vulto A, Simoens S. Analysis of the Italian generic medicines retail market: recommendations to enhance long-term sustainability. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2015;15(1):33-42.

110. Godman B, Bishop I, Finlayson AE, Campbell S, Kwon HY, Bennie M. Reforms and initiatives in Scotland in recent years to encourage the prescribing of generic drugs, their influence and implications for other countries. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2013;13(4):469-82.

111. McGinn D, Godman B, Lonsdale J, Way R, Wettermark B, Haycox A. Initiatives to enhance the quality and efficiency of statin and PPI prescribing in the UK: impact and implications. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2010;10(1):73-85.

112. Bennie M, Godman B, Bishop I, Campbell S. Multiple initiatives continue to enhance the prescribing efficiency for the proton pump inhibitors and statins in Scotland. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2012;12(1):125-30.

113. UK Departemnt of Health and Social Care. Health service medical supplies (costs) bill factsheet. Updated 8 November 2016 [homepage on the Internet]. [cited 2019 Mar 14]. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/health-service-medical-supplies-costs/health-service-medical-supplies-costs-bill-factsheet

114. Bundesministerium für Gesundheit. Preismoratorium für Arzneimittel [homepage on the Internet]. [cited 2019 Mar 14]. Available from: https://www.bundesgesundheitsministerium.de/themen/krankenversicherung/arzneimittelversorgung/preismoratorium.html

115. Bundesministerium für Gesundheit. Sozialgesetzbuch (SGB) Fünftes Buch (V) – Gesetzliche Krankenversicherung – (Artikel 1 des Gesetzes v. 20. Dezember 1988, BGBl. I S. 2477). § 130a Rabatte der pharmazeutischen Unternehmer [homepage on the Internet]. [cited 2019 Mar 14]. Available from: https://www.gesetze-im-internet.de/sgb_5/__130a.html.

116. UK Government. Pharma firms accused of illegal agreements over life-saving drug. 28 February 2019 [homepage on the Internet]. [cited 2019 Mar 14]. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/news/pharma-firms-accused-of-illegal-agreements-over-life-saving-drug

117. European Commission. Antitrust: Commission opens formal investigation into Aspen Pharma’s pricing practices for cancer medicines. 2017. Available at URL: file:///C:/Users/mail/Downloads/IP-17-1323_EN.pdf

118. Department of Health. Press Release. Ireland to open negotiations with Belgium, the Netherlands, Luxembourg and Austria on drug pricing and supply – Minister Harris [homepage on the Internet]. [cited 2019 Mar 14]. Available from:http://health.gov.ie/blog/press-release/ireland-to-open-negotiations-with-belgium-the-netherlands-luxembourg-and-austria-on-drug-pricing-and-supply-minister-harris/

119. European Observatory. How can voluntary cross-border collaboration in public procurement improve access to health technologies in Europe? [homepage on the Internet]. [cited 2019 Mar 14]. Available from: http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0009/331992/PB21.pdf?ua=1

120. Ferrario A, Humbert T, Kanavos P, Pedersen HB. Strategic procurement and international collaboration to improve access to medicines. Bull World Health Organ. 2017;95(10):720-2.

121. Vogler S, Zimmermann N, Babar ZU. Price comparison of high-cost originator medicines in European countries. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res.2017;17(2):221-30.

122. Vogler S, Kilpatrick K, Babar ZU. Analysis of medicine prices in New Zealand and 16 European countries. Value in Health. 2015;18(4):484-92.

123. Bochenek T, Abilova V, Alkan A, Asanin B, de Miguel Beriain I, Besovic Z, et al. Systemic Measures and Legislative and Organizational frameworks aimed at preventing or mitigating drug shortages in 28 European and Western Asian countries. Frontiers in pharmacology. 2017;8:942.

124. Godman B, Bucsics A, Vella Bonanno P, Oortwijn W, Rothe CC, Ferrario A, et al. Barriers for Access to new medicines: searching for the balance between rising costs and limited budgets. Front Public Health. 2018;6:328.

|

Author for correspondence: Brian Godman, BSc, PhD, Strathclyde Institute of Pharmacy and Biomedical Sciences, University of Strathclyde, Glasgow G4 0RE, UK |

Disclosure of Conflict of Interest Statement is available upon request.

Copyright © 2019 Pro Pharma Communications International

Permission granted to reproduce for personal and non-commercial use only. All other reproduction, copy or reprinting of all or part of any ‘Content’ found on this website is strictly prohibited without the prior consent of the publisher. Contact the publisher to obtain permission before redistributing.

Source URL: https://gabi-journal.net/pricing-of-oral-generic-cancer-medicines-in-25-european-countries-findings-and-implications.html

Author byline as per print journal: Steven Simoens, PhD; Claude Le Pen, PhD; Niels Boone, PharmD; Ferdinand Breedveld, MD, PhD; Antonella Celano; Antonio Llombart-Cussac, MD, PhD; Frank Jorgensen, MPharm, MM; Andras Süle, PhD; Ad A van Bodegraven, MD, PhD; Rene Westhovens, MD, PhD; Jo De Cock

|

Introduction/Objectives: This manuscript aims to provide guidance to policymakers with a view to fostering a fair, competitive and sustainable market for off-patent biologicals and biosimilars in Europe. |

Submitted: 6 June 2018; Revised: 13 July 2018; Accepted: 13 July 2018; Published online first: 20 July 2018

Reference biologicals are originator medicinal products made by or derived from living organisms using biotechnology. When the patent and exclusivity rights on a reference biological expire, biosimilar medicines can enter the market. A biosimilar is a biological product that contains a version of the active substance of an already authorized reference biological medicinal product [1]. On the one hand, the European Medicines Agency (EMA) and regulatory authorities guarantee the quality, safety and efficacy of registered biosimilars. After a decade of experience with biosimilar products, no unexpected concerns have emerged [2, 3]. Also, health economists of international organizations refer to the important savings potential of a competitive off-patent biologicals and biosimilars market and to the opportunity to improve patient access. On the other hand, the market access, uptake and price evolution of off-patent biologicals and biosimilars stay heterogeneous between countries and between therapeutic classes, e.g. erythropoiesis-stimulating agents, granulocyte colony-stimulating factors, human growth hormones, antitumour necrosis factors, follitropin alfa and insulins [4].

This implies that European countries are not realizing the full potential of the off-patent biologicals and biosimilars market. In this respect, the European Commission and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) have argued that competition in the off-patent biologicals and biosimilars market could yield substantial savings to healthcare systems [5, 6]. To capture these savings, the European Commission (Directorate-General for Internal Market, Industry, Entrepreneurship and small and medium-sized enterprises [SMEs]) has supported a multi-stakeholder approach and has hosted multiple workshops with a view to facilitating access to and uptake of biosimilars [7, 8]. The European Commission also issued a consensus information paper in 2013, an information document for patients in 2016, and an information guide for healthcare professionals in 2017 [8].

However, the development of a competitive market for off-patent biologicals and biosimilars is not certain because of numerous factors including the risk of non-recognition of the difference between biosimilars and generics, physician and patient lack of confidence, and unbalanced payer pricing and procurement policies. In particular, after a decade of experience with these products, it seems clear that a simple logic whereby price reductions multiplied by prescribed volumes of reference biologicals will lead to potential savings is misleading and inappropriate. Price reductions alone do not appear to be the key factor guaranteeing greater market penetration of biosimilars [4]. On the contrary, price reductions can lead to a race to the bottom, preventing manufacturers to enter the market.

It is also important that policymakers keep in mind that biosimilars (where the reference product is a biological medicine) are inherently different from generics (where the reference product is a chemically synthesized medicine), due to their more elaborate size and structure of the molecule, higher risks and costs of research and development, more complex manufacturing processes, extended development times, and the need to institute post-marketing pharmacovigilance programmes [9]. Therefore, policy must be adapted to the specific needs of the off-patent biologicals and biosimilars market.

Developing a competitive market for off-patent biologicals and biosimilars in Europe is a necessary condition for stakeholders to reap the benefits that such competition may create. These benefits include more control of drug expenditure for healthcare payers, expanded access to health care for patients, increased treatment choices for physicians, and headroom for innovation for industry. The development of such a market requires the implementation of a long-term, sustainable and specific policy framework based on a multi-stakeholder approach. Thus, the aim of this manuscript is to provide guidance to policymakers with a view to fostering a fair, competitive and sustainable market for off-patent biologicals and biosimilars in Europe, taking into account the role of all stakeholders.

This manuscript has been commissioned by the Belgian National Institute for Health and Disability Insurance. Individuals and stakeholder representatives from patient groups, clinicians, healthcare professional organizations, government bodies, and industry have participated in a series of roundtable discussions in 2016–2017 which have contributed to the development of the manuscript. These discussions were held under Chatham House Rules. This manuscript represents the authors’ views on the topic which have been informed by their participation in the roundtable discussions and do not represent the position of their respective organization/institution.

When developing guidance to policymakers, the focus of this manuscript is specifically on those product classes for which patent expiry and loss of exclusivity has recently occurred or is imminent, such as monoclonal antibodies for the treatment of inflammatory diseases (rheumatoid arthritis, inflammatory bowel diseases, psoriasis) and cancers.

Supply-side incentives

A building block of a fair, competitive and sustainable market for off-patent biologicals and biosimilars in Europe, see Box 1, relates to the need to put in place appropriate supply-side incentives. In particular, policymakers need to design smart procurement and reimbursement mechanisms with a view to allowing physicians to prescribe off-patent biologicals and biosimilars based on scientific evidence and clinical experience. The design of such mechanisms needs to be anchored in good clinical practice, which will evolve with knowledge, and needs to respect the European legislative framework on public procurement [10, 11]. Physician involvement in procurement and reimbursement mechanisms is vital to ensure that physicians maintain the freedom to prescribe. Also, there is a need to build up technical and practical expertise, and exchange experiences between countries with respect to designing smart procurement and reimbursement mechanisms.

Box 1: Recommendations for developing policy on off-patent biologicals and biosimilars in Europe

In the hospital setting, tendering mechanisms, i.e. public procurement mechanisms for medicines based on competition between pharmaceutical suppliers [12], can be applied to off-patent biologicals and biosimilars nationally or locally, although future studies need to provide guidance to policymakers on how to optimize the features of these mechanisms, such as the frequency of tenders, the criteria to grant the tender, the reward for the winner(s), and the number of winners. For example, tendering may lead to a market where only one medicine is available, i.e. the ‘winner takes all’ principle, and shortages may occur if that supply fails. Thus, tendering mechanisms need to be monitored to ensure that several pharmaceutical suppliers participate and that the market does not fail [13].

In the ambulatory care setting, off-patent biologicals and biosimilars can be included in a reference pricing system, which sets a common reimbursement level for a group of medicines. Policymakers need to appreciate that the application of a reference pricing system could imply that off-patent biologicals and biosimilars included in the same reference group could be used interchangeably (which indicates that a patient can be alternated between products whilst expecting the same clinical outcomes in respect to efficacy and safety as if no alternation were to occur) [14]. In such cases, the relevant policymaker should clarify the status of the medicine.