|

Abstract: |

Submitted: 9 January 2017; Revised: 12 February 2017; Accepted: 13 February 2017; Published online first: 27 February 2017

In light of the clinical trials leading to the authorization of infliximab biosimilars, PLANETRA and PLANETAS and the recently published NOR-Switch study [1], the Austrian Medicines and Medical Devices Agency takes a position in the state-wide journal of the Austrian social insurance for health system payers gives doctors an updated, more positive opinion about the controversial issue of interchangeability [2].

Decisions related to the interchangeability and/or substitution of biosimilars rely on nationally competent authorities and are outside the remit of the European Medicines Agency (EMA). Individual nations independently decide if a biosimilar should be regarded as suitable for switching. To decide if patients’ medication can be switched from the originator to a biosimilar, European Union (EU) Member States have access to the European network of data and scientific evaluations performed by EMA in order to substantiate their decision. As such, the decisions made by the 28 EU Member States rely on their respective national authorities, which could lead to different approaches being adopted by each Member State.

In general, there appears to be broad disapproval of automatic biosimilar substitution by pharmacists without the involvement of doctors [3]. Following concerns from physicians, in 2013, Austria made reassurances that no automatic substitution of a reference product with a biosimilar on the pharmacy level will take place, but that, in accordance with EMA such a decision will always involve a well-informed physician [4]. At that time and acting as a representative of the Austrian Medicines and Medical Devices Agency, the author of this paper, Dr Baumgärtel, recommended that there was a good opportunity for Austrian doctors to increase the uptake of biosimilars by the Austrian health system through promoting their use as starting treatments for new patients, rather than by switching existing patients’ therapies to biosimilars [4]. This was based on previous research carried out by the Austrian social insurance system following the introduction of generics. This showed that when a new patient’s treatment was started with generics, this had a marked effect on increasing a health systems’ generics usage [5], so the same can be expected from biosimilars [3].

It is expected that doctors are likely to come under pressure to select treatment with biosimilars to save money for the public health system [4]. In Austria, biosimilars are priced in the same way as generics. This means that, in a complex system of price reductions, after biosimilar market entry, biosimilars must be priced at 48 to 60 per cent below the cost of the originator, allowing room for substantial savings.

Fortunately, there is now an ever-growing bank of safety and efficacy data related to switching that comes from clinical trials and pharmacovigilance databases for biotechnology products. These include recombinant growth hormones, erythropoietins, granulocyte colony-stimulating factors [5], and more recently data for monoclonal antibody biosimilars like infliximab [1]. As a result, Austria will now take the next step, and open the possibility of switching to biosimilars.

For the first time, the Austrian Medicines and Medical Devices Agency stated following official position: ‘Biosimilars are high-tech and high quality products. They are authorized within the framework of European centralized procedures, tested according to highest state-of-the-art knowledge and are assessed to strictest and up-to-date points of view. Prescribing biosimilars to treatment-naïve patients as well as even an exchange of the biosimilar for an originator biological is appropriate, provided that this is done under supervision of the prescribing physician. Data from recent studies, and from safety monitoring and pharmacovigilance trials, are already leading us in a positive direction towards increased biosimilar uptake and interchangeability as well. We expect pronounced evidence to increase even further in the months and years to come’ [2].

This position statement is now expected to further increase the uptake of biosimilars and the acceptance of the idea of interchangeability in clinical care. There may also be benefits seen in reduction of the ever-rising costs experienced by Austria’s health system.

Competing interests: None.

Provenance and peer review: Commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

1. GaBI Online – Generics and Biosimilars Initiative. NOR-SWITCH study finds biosimilar infliximab not inferior to originator aplasia [www.gabionline.net]. Mol, Belgium: Pro Pharma Communications International; [cited 2017 Feb 12]. Available from: www.gabionline.net/Biosimilars/Research/NOR-SWITCH-study-finds-biosimilar-infliximab-not-inferior-to-originator

2. Baumgärtel C. Biosimilars – How similar is biosimilar? ÖkoMed, Ökonomie und Praxis. 2016;(2):2-4. German.

3. GaBI Online – Generics and Biosimilars Initiative. Biosimilar substitution in the EU [www.gabionline.net]. Mol, Belgium: Pro Pharma Communications International; [cited 2017 Feb 12]. Available from: www.gabionline.net/Biosimilars/Research/Biosimilar-substitution-in-the-EU

4. Baumgärtel C. Austria increases dialogue in order to involve physicians more with biosimilars. Generics and Biosimilars Initiative Journal (GaBI Journal). 2013;2(1):8. doi:10.5639/gabij.2013.0201.003

5. Upper Austrian Health Insurance Fund. Generika – eine Einstellungssache. Ökonomie in der Praxis. 2011;(3):5-6. German.

6. Ebbers HC, Muenzberg M, Schellekens H. The safety of switching between therapeutic proteins. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2012;12(11):1473-85.

|

Author: Christoph Baumgärtel, MD, MSc, Senior Scientific Expert, Coordination-Point of Risk-Management to Head of Agency, AGES Austrian Medicines and Medical Devices Agency and Austrian Federal Office for Safety in Health Care, EMA European Expert, Vice-Chair of Austrian Prescription Commission, 5 Traisengasse, AT-1200 Vienna, Austria |

Disclosure of Conflict of Interest Statement is available upon request.

Copyright © 2017 Pro Pharma Communications International

Permission granted to reproduce for personal and non-commercial use only. All other reproduction, copy or reprinting of all or part of any ‘Content’ found on this website is strictly prohibited without the prior consent of the publisher. Contact the publisher to obtain permission before redistributing.

Source URL: https://gabi-journal.net/austrian-medicines-authority-positive-towards-biosimilar-interchangeability.html

|

Abstract: |

Submitted: 27 May 2015; Revised: 5 June 2015; Accepted: 8 June 2015; Published online first: 22 June 2015

Generic medicinal products are subject to detailed authority assessment in Austria, including the thorough examination of safety and efficacy data. The competent medicines authorities in Austria, and in the European Union (EU), will only issue authorization for their respective markets if all applicable legal and scientific requirements are fulfilled. It is now obvious for most experts in the fields of clinical prescribing and dispensing, after more than 30 years of worldwide experience with generics, that generic drugs present a safe and efficacious alternative to established medicinal products [1, 2]. They are rigorously tested and their safety and efficacy is continuously controlled.

In contrast to originator products, which usually undergo an expensive and protracted development that can take up to 15 years, the development of generic drug products is a relatively quick and inexpensive process. This allows generic drugs to be sold at a lower price. In fact, the increased use of generic medicines is essential to sustain healthcare systems faced by an ever-increasing pressure on resources [3, 4]. Ageing populations and the continued launch of new premium-priced medicines, priced at over Euros 70,000 per patient per year or course are some of the factors causing these pressures.

Austrian health insurance will pay for a patient’s medicine if that medicine is listed in the so-called Erstattungscodex (Austrian reimbursement code). The Main Association of Austrian Social Security Organisations decides whether a new product will be listed. To do this, they assess efficacy and value of a new medicine by conducting a pharmacological evaluation, a medical-therapeutic evaluation and a health-economic evaluation. Before a medicine can be listed, its therapeutic value is compared with that of existing medicines, and average prices for those medicines across the EU are taken into account. For generics, this procedure is an abbreviated one and follows fixed, unique rules.

The moment the first generic drug enters the market; it has to be at least 48% below the price of the originator. This price reduction has gradually increased – from 44% in 2004, to 46% in 2005, finally reaching 48% in 2006. If the company that produces the originator wants it to stay in the reimbursement code, it will need to decrease the originator’s price by 30% within three months. When a second generic drug enters the market, it will need to be priced 15% below the price of the first generic drug to become listed; a third generic drug must be priced at an additional 10% below the price of the second generic drug. Remarkably, the price of the originator and also of the first and the second generics must again go down to the price of the third generic drug within three months if they are to stay listed. At this point, prices are 60.2% below the former originator price. However, this does not mean that every product after that will have the same price forever; every marketing authorization holder can, and usually will, lower the price again, to have a prescribing advantage. Further price decreases are often seen down to -80% or -90% of the former starting price of an originator.

It is estimated that Austria currently achieves savings of up to two billion Euros a year thanks to cheaper generics and their price lowering effect on originators [5]. It was reported recently that Austria’s healthcare payers could have saved an additional quarter of a billion Euros in 2011 if physicians had prescribed generics to all patients whenever they were available [6, 7]. This is only theoretical, however, as it would mean a 100% generics penetration rate in the replaceable segment. Taking into account a more realistic generics penetration rate of 75%, a more likely saving would have been Euros 150 million. The generics penetration rate in Austria is currently slightly above 40%.

A new study has again underlined these potential savings for Austria [8]. The nationwide cohort study showed that substituting originators with generics could save up to Euros 72 million in just three therapeutic indications: hypertension, hyperlipidaemia and diabetes mellitus. This study at the Center for Medical Statistics, Informatics and Intelligent Systems (CeMSIIS) at the Medical University of Vienna, Austria, analysed data collected from 8.3 million people across Austria between 2009 and 2012 (equivalent to 98.5% of the insured population of Austria). The study concluded that potential annual savings of 18% would be possible if generics uptake was stepped up in these three disease areas, which currently cost the annual health budget Euros 401 million.

Health insurance companies spent Euros 231.3 million on anti-hypertensive medicines, Euros 77.8 million on lipid-lowering medicines and Euros 91.9 million on medicines for diabetes. The calculations show that substituting these medicines with cheaper generic versions could have saved Euros 52.2 million (22.6%), Euros 15.9 million (20.5%) and Euros 4.1 million (4.5%) respectively, in costs.

Importantly, some additional measures might be necessary to achieve these ambitious goals in Austria, where the generics penetration rate is currently no better than average compared with other European countries. For example, Austria has not implemented pro-generics measures such as INN (International Nonproprietary Name) prescribing, compulsory substitution, reference pricing, additional copayments for a more expensive product than the referenced price, or financial incentives to prescribers, dispensers or patients. This means that Austria mainly relies on its pricing system and on doctors prescribing generics.

These additional measures must be taken if a higher generics penetration rate and the full savings potential is to be achieved by Austria [5]:

It remains to be seen how big the overall savings will be for national health budgets in Austria, not only with generics, but also taking biosimilars into account, as more and more of these products are now entering the market. Globally, it is expected that, over the next 10 years, biosimilars could save more than US&40 billion in health costs worldwide. Biosimilar prices are expected to be 15% to 35% below the originator biologicals prices [9]. The same savings are anticipated not only worldwide, but also just for the US market, suggesting that potential worldwide savings could be considerably higher [10]. Savings of at least Euros 11.8 billion are expected between now and 2020 with the use of biosimilars in Europe alone [11].

Regarding biosimilars, no specific data in this interesting field is yet available for Austria. However, the Austrian Main Association of Social Security Organisations has made it clear that it will price future biosimilars in the same way as they currently price generics, which means that premium priced biotechnology drugs, including monoclonal antibodies, will see pronounced price reductions of 60% or more. Since the question of substitution and switching from an originator to a biosimilar is not yet answered, it is expected that the biosimilar penetration rate in Austria will not, at least to begin with, be as high as that seen with generics. It is expected that only new patients will be started on a biosimilar, since switching for existing patients is not yet fully endorsed [12]. The saving potential in Austria could grow further with the increasing availability of new biosimilars. It is estimated that more than 300 monoclonal antibodies are in development in more than 200 indications, and that more than 20 blockbuster biotech drugs will lose patent protection by 2020. This, coupled with the fact that the use of biologicals is growing at a much higher rate than the overall pharmaceutical market, suggests there will be more room for considerable savings in Austria.

Competing interest: None.

Provenance and peer review: Commissioned; internally peer reviewed.

References

1. Kesselheim AS, Misono AS, Lee JL, Stedman MR, Brookhart MA, Choudhry NK, et al. Clinical equivalence of generic and brand-name drugs used in cardiovascular disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2008;300(21):2514-26.

2. Baumgärtel C. Myths, questions, facts about generic drugs in the EU. Generics and Biosimilars Initiative Journal (GaBI Journal). 2012;1(1):34-8. doi:10.5639/gabij.2012.0101.009

3. Dylst P, Vulto A, Godman B, Simoens S. Generic medicines: solutions for a sustainable drug market? Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2013;11(5):437-43.

4. Godman B, Shrank W, Wettermark B, Andersen M, et al. Use of generics – a critical cost containment measure for all healthcare professionals in Europe? Pharmaceuticals. 2010; 3(8):2470-94.

5. Baumgärtel C. [Generics in Austria]. Generika in Österreich und ihre Bedeutung für das Gesundheitssystem. AV Akademikerverlag 2013, ISBN-13: 978-3639491265,106-10. German.

6. Austrian Generics Association. [Current prices of medicines]. Arzneimittelkosten in Österreich – aktuelle Zahlen. 2012 Aug 27. German.

7. Baumgärtel C. Austria could save Euros 256 million by using more generics. Generics and Biosimilars Initiative Journal (GaBI Journal). 2012;1(3-4):144. doi:10.5639/gabij.2012.0103-4.038

8. Heinze G, Hronsky M, Reichardt B, Baumgärtel C, Müllner M, Bucsics A, et al. Potential savings in prescription drug costs for hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and diabetes mellitus by equivalent drug substitution in Austria: a nationwide cohort study. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2015 Apr;13(2):193-205.

9. Biosimilars entering the U.S. market are likely to face multiple challenges. Tufts CSDD. Impact Reports Single Issue. March/April 2015;17(2).

10. GaBI Online – Generics and Biosimilars Initiative. Biosimilars could save US&44.2 billion over 10 years [www.gabionline.net]. Mol, Belgium: Pro Pharma Communications International; [cited 2015 Jun 5]. Available from: www.gabionline.net/Reports/Biosimilars-could-save-US-44.2-billion-over-10-years

11. Hausstein R, Millas C, Höer A, Häussler B, Saving money in the European healthcare systems with biosimilars. Generics and Biosimilars Initiative Journal (GaBI Journal). 2012;1(3-4).120-6. doi:10.5639/gabij.2012.0103-4.036

12. Baumgärtel C. Austria increases dialogue in order to involve physicians more with biosimilars. Generics and Biosimilars Initiative Journal (GaBI Journal). 2013;2(1):8. doi:10.5639/gabij.2013.0201.003

|

Author: Christoph Baumgärtel, MD, MSc, Senior Scientific Expert, Coordination Point to Head of Agency, AGES Austrian Medicines and Medical Devices Agency and Austrian Federal Office for Safety in Health Care, EMA European Expert, Vice Chair of Austrian Prescription Commission, 5 Traisengasse, AT-1200 Vienna, Austria |

Disclosure of Conflict of Interest Statement is available upon request.

Copyright © 2015 Pro Pharma Communications International

Permission granted to reproduce for personal and non-commercial use only. All other reproduction, copy or reprinting of all or part of any ‘Content’ found on this website is strictly prohibited without the prior consent of the publisher. Contact the publisher to obtain permission before redistributing.

Source URL: https://gabi-journal.net/substantial-savings-with-generics-in-austria-and-still-room-for-more.html

Submitted: 24 January 2015; Revised: not applicable; Accepted: 27 January 2015; Published online first: 30 January 2015

The ‘International Generic Drug Regulators Pilot’ (IGDRP) seems to be a true model for the future of authorization processes. It was first founded back in April 2012 with the aim to promote the international collaboration within authorization processes of generic medicines. Members of IGDRP are Australia, Brazil, Canada, China, Chinese Taipei, EU (European Union), Japan, Republic of Korea, Mexico, New Zealand, Russia, Singapore, South Africa, Switzerland and USA, respectively, their national competent authorities, European Directorate for the Quality of Medicines & HealthCare and World Health Organization (observer). This means that a global work sharing process regarding generics authorization applications, the regulatory and scientific assessment thereof, and finally the authorization itself is ready to start.

In the first phase of the pilot Australia, Canada, Chinese Taipei and Switzerland are participating and it was agreed to use the Decentralised Authorisation Procedure (DCP) of the EU as an ‘Information-sharing’ model. This means that an application for a marketing authorisation (MAA) of a generic medicinal product is filed by the applicant (criteria for eligibility, see the link in [1]) in a synchronized manner with all authorities, i.e. with the Reference Member State (RMS) and with all Concerned Member States (CMS) of the DCP within the EU, and – also at the same time – with other IGDRP-member competent authorities (external of EU). The RMS will then provide the reference scientific assessment report of such an application to all these authorities – even to the EU-externals – during the ongoing DCP procedure, see Figure 1.

With participation in the pilot phase, applicants gain the unique possibility to obtain a marketing authorization in different markets inside and outside of the EU by a coordinated process – provided that the applicant agreed to share the DCP assessment reports with some or all of the non-EU agencies. The ‘initial expression of interest’ – phase of the first pilot round is now already over and the first procedures have already started. In total about 20 requests have been submitted. The Austrian Authority – AGES Austrian Medicines and Medical Devices Agency, for example, is also participating as a selected RMS right from the beginning of IGDRP. The experience gained in the pilot phase will contribute in a valuable way to establishing best practice for the future of this exciting project. Noteworthy, it has been recently agreed by the European Medicines Agency and the IGDRP Steering Committee to also extend the Information-sharing pilot to Centrally Authorised Products (CAPs) procedures, paving the way to an even broader application of the project.

A new era of authorization of medicinal products might have begun by the start of the IGDRP project. IGDRP could indeed lead to more harmonized scientific views and better balanced generic drug assessments, not only within the EU – which was already managed by the last update of the bioequivalence guideline in 2010 – but now also on a broader international level. It should facilitate an efficient and consistent assessment procedure of generic medicinal products while reducing regulatory burden for applicants at the same time. This in fact could speed up the authorization processes to bring low priced generics even faster to the international markets to benefit health budgets.

Competing interests: None.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; internally peer reviewed.

DI Dr Katharina Gazda-Pleban, Regulatory Expert, AGES Austrian Medicines and Medical Devices Agency and Austrian Federal Office for Safety in Health Care, 5 Traisengasse, AT-1200 Vienna, Austria

References

1. Co-ordination Group for Mutual Recognition and Decentralised Procedures – Human. Information sharing pilot for the evaluation of generic drug applications involving the decentralised procedure of the European Union [homepage on the Internet]. 2015 [cited 2015 Jan 24]. Available from: http://www.hma.eu/451.html

|

Author for correspondence: Christoph Baumgärtel, MD, MSc, Senior Scientifi c Expert, Coordination-Point to Head of Agency, AGES Austrian Medicines and Medical Devices Agency and Austrian Federal Offi ce for Safety in Health Care, EMA European Expert, Vice-Chair of Austrian Prescription Commission, 5 Traisengasse, AT-1200 Vienna, Austria |

Disclosure of Conflict of Interest Statement is available upon request.

Copyright © 2015 Pro Pharma Communications International

Permission granted to reproduce for personal and non-commercial use only. All other reproduction, copy or reprinting of all or part of any ‘Content’ found on this website is strictly prohibited without the prior consent of the publisher. Contact the publisher to obtain permission before redistributing.

Source URL: https://gabi-journal.net/generic-authorization-groundbreaking-regulatory-approach-to-closer-international-cooperation-on-the-rise-igdrp.html

Submitted: 2 March 2014; Revised: 7 March 2014; Accepted: 8 March 2014; Published online first: 21 March 2014

The guideline ‘Note for guidance on modified release oral and transdermal dosage forms: Section II (Pharmacokinetic and clinical evaluation)’ [1] was issued over 10 years ago, and the need for revision was recognized in 2010. An international group of experts, led by Austrian members of the Pharmacokinetics Working Party, is responsible for its implementation. They have joined forces with the Quality Working Party, which revises guidelines on the quality of such products, and various other expert groups of the European Medicines Agency (EMA). A draft version was recently produced and approval obtained from EMA’s Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use; it was then posted on the EMA website for feedback [2].

This guideline deals specifically with medicinal products that use a modified drug release mechanism. Several different product groups, in particular all modified oral dosage forms, all transdermal delivery systems, as well as subcutaneous or intramuscular depot formulations, are covered by the recommendations.

Two principles of the modification can be distinguished:

Today, numerous different release mechanisms are increasingly being incorporated into new products. The simultaneous use of galenic components with both immediate and prolonged release properties achieves a rapid onset of action combined with a prolonged duration of effects. In people suffering from chronic diseases where treatment needs to be adjusted to a circadian rhythm of their symptoms, a time-related single or multiple drug release, a so-called pulsatile release, from a single tablet might lead to improved treatment outcome.

The new guideline will provide detailed rules for the conduct of clinical trials of these drug products. These guidelines will include:

Two new, additional pharmacokinetic parameters to be used for the evaluation and comparison of the plasma profile of drugs were established during the guideline revision process: Cτ (concentration at the end of the dosing interval) and partialAUC (the area under the concentration time curve during a predefined and relevant portion of the whole AUC).

The necessity and usefulness of conducting bioequivalence studies after repeated dosing (steady-state or multiple dose studies) was discussed in detail, and the latest scientific publications related to this topic were also taken into account. In contrast to applicable US FDA guidelines, it was decided to continue to request these studies as a requirement for the approval of certain generic drugs [3]. The failure to conduct such a study, however, can be justified by proving that no or negligible accumulation of the active substance will occur in patients following the recommended dosage regimen.

The intensity of the discussions is reflected in the fact that 22 draft versions were developed before publication of internal draft 23 on 15 March 2013. The deadline for receipt of comments closed on 15 September 2013. Over 400 pages containing thousands of comments have been received from industry representatives, doctors and patient organizations, and these are now being carefully evaluated, discussed and responded to. By the middle of 2014, a new version of the guideline, incorporating these discussions and comments, will be made available.

Competing interests: None.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; internally peer reviewed.

Jan Neuhauser, MD

AGES MEA/BASG

References

1. European Agency for the Evaluation of Medicinal Products. Note for guidance on modified release oral and transdermal dosage forms: Section II (Pharmacokinetic and clinical evaluation). CPMP/EWP/280/96 Corr *. 28 July 1999 [homepage on the Internet]. 2009 May 27 [cited 2014 Mar 7]. Available from: http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Scientific_guideline/2009/09/WC500003126.pdf

2. European Medicines Agency. Guideline on the pharmacokinetic and clinical evaluation of modified release dosage forms. EMA/CPMP/EWP/280/96 Corr1. Draft XXIII. 21 February 2013 [homepage on the Internet]. 2013 Aug 19 [cited 2014 Mar 7]. Available from: http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Scientific_guideline/2013/03/WC500140482.pdf

3. Baumgärtel C. New product-specific bioequivalence guidance. Generics and Biosimilars Initiative Journal (GaBI Journal). 2014;3(1):29. doi: 10.5639/gabij.2014.0301.009

|

Author for correspondence: Christoph Baumgärtel, MD, MSc, Department Head, Department Safety and Efficacy Assessment of Medicinal Products, Institute Marketing Authorisation of Medicinal Products & LCM, AGES MEA–Austrian Medicines and Medical Devices Agency, and Austrian Federal Office for Safety in Health Care (BASG), European Expert in Pharmacokinetics Working Party of EMA, Member of Austrian Prescription Commission, 5 Traisengassee, AT-1200 Vienna, Austria |

Disclosure of Conflict of Interest Statement is available upon request.

Copyright © 2014 Pro Pharma Communications International

Permission granted to reproduce for personal and non-commercial use only. All other reproduction, copy or reprinting of all or part of any ‘Content’ found on this website is strictly prohibited without the prior consent of the publisher. Contact the publisher to obtain permission before redistributing.

Source URL: https://gabi-journal.net/new-eu-guidance-for-the-evaluation-of-medicinal-products-with-modified-drug-release-will-be-finished-by-the-middle-of-2014.html

|

Abstract: |

Submitted: 2 January 2014; Revised: 6 January 2014; Accepted: 7 January 2014; Published online first: 20 January 2014

Official draft guidance has recently become available for 16 new active substances that have either lost patent protection, will imminently lose it, or whose data-protection period has recently expired. The guidance establishes which criteria should be used when investigating the bioequivalence of a certain generic drug to its originator for these 16 substances.

The so-called product-specific bioequivalence guidance was published on 15 November 2013 [1], after development by the Pharmacokinetics Working Party (PKWP) of the European Medicines Agency (EMA), links to the published product-specific bioequivalence guidances (PSBEGS) can be found on the EMA website [2, 3].

By clearly stating which criteria should apply to these active substances, problems that have repeatedly led to questions and uncertainties during product development and application for marketing authorization can be avoided in the future.

Clearer guidance can sometimes resolve controversial issues: for example, establishing for distinct substances which strength of medicine is suitable and should be investigated in a bioequivalence trial; determining whether a study should be conducted in a fasted or fed state so that it is clear whether individuals participating in a trial should take medicines with food; or, instead of conducting a bioequivalence trial, a waiver using the biopharmaceutics classification system approach can be applied, which means that in vitro data will mainly suffice.

Product-specific bioequivalence guidance will make it clear for applicants whether the conventional bioequivalence criteria of 80–125% should apply, whether the 90–111% interval is required, or, in the case of highly variable drugs, a broadened acceptance margin of up to 70–143% may be chosen. Additionally, it will become clear if the parent of an active substance has to be measured in the plasma or the metabolite, or even both. It will also distinguish when it is appropriate to use healthy volunteers in a trial compared with patients.

The aim of product-specific bioequivalence guidance is to rationalize the criteria applied to substances in the authorization process, thereby giving companies more planning security when drafting an application, including the planning and carrying out of bioequivalence studies. It also gives the EU and all European national medicines authorities a single harmonized view on which criteria are deemed well founded and necessary for market authorization of generics with certain active substances.

Interested parties and stakeholders can forward comments on each of these active substances to pkwpsecretariat@ema.europa.eu on or before 15 February 2014.

The 16 published product-specific bioequivalence guidance substances are as follows:

– Capecitabine

– Carglumic acid

– Dasatinib

– Emtricitabine/Tenofovir

– Erlotinib

– Imatinib

– Memantine

– Miglustat

– Oseltamivir

– Posaconazole

– Repaglinide

– Sirolimus

– Sorafenib

– Tadalafil

– Telithromycin

– Voriconazole

As a member of EMA PKWP that drafted the guidance, I fully support this initiative, which is the first of its kind and highly essential for pharmaceutical companies. We are actively encouraging participation of stakeholders during the consultation process. Please use this opportunity to comment on the 16 draft guidelines.

Competing interests: None.

Provenance and peer review: Commissioned; internally peer reviewed.

References

1. GaBI Online – Generics and Biosimilars Initiative. EMA releases product-specific bioequivalence guidelines [www.gabionline.net]. Mol, Belgium: Pro Pharma Communications International; [cited 2014 Jan 6]. Available from: www.gabionline.net/Guidelines/EMA-releases-product-specific-bioequivalence-guidelines

2. European Medicines Agency. EMA promotes consistent development of bioequivalence studies through product-specific guidance [homepage on the Internet]. 2013 Nov 11 [cited 2014 Jan 6]. Available from: http://www.ema.europa.eu/ema/index.jsp?curl=pages/news_and_events/news/2013/11/news_detail_001958.jsp&mid=WC0b01ac058004d5c1

3. European Medicines Agency. Clinical efficacy and safety: clinical pharmacology and pharmacokinetics [homepage on the Internet]. [cited 2014 Jan 6]. Available from: http://www.ema.europa.eu/ema/index.jsp?curl=pages/regulation/general/general_content_000370.jsp&mid=WC0b01ac0580032ec5

|

Author: Christoph Baumgärtel, MD, MSc, Department Head, Department Safety and Efficacy Assessment of Medicinal Products, Institute Marketing Authorisation of Medicinal Products & LCM, AGES MEA–Austrian Medicines and Medical Devices Agency, and Austrian Federal Office for Safety in Health Care (BASG), European Expert in Pharmacokinetics Working Party of EMA, Member of Austrian Prescription Commission, 5 Traisengassee, AT-1200 Vienna, Austria |

Disclosure of Conflict of Interest Statement is available upon request.

Copyright © 2014 Pro Pharma Communications International

Permission granted to reproduce for personal and non-commercial use only. All other reproduction, copy or reprinting of all or part of any ‘Content’ found on this website is strictly prohibited without the prior consent of the publisher. Contact the publisher to obtain permission before redistributing.

Source URL: https://gabi-journal.net/new-product-specific-bioequivalence-guidance.html

|

Abstract: |

Submitted: 18 November 2012; Revised: 3 December 2012; Accepted: 4 December 2012; Published online first: 7 December 2012

In September 2012, Austrian doctors were given reassurance that pharmacists would not make the decision to automatically switch patients from brand-name drugs to biosimilars without the involvement of doctors, and that stringent regulations were in place regarding the safety and efficacy of biosimilars.

In September 2012, the Austrian Society for Pharmaceutical Medicine together with representatives of the Austrian Regulatory Authority and the Austrian Main Association of Social Health Insurance gave hospital and resident doctors an information update about the meaning and potential use of biosimilars, particularly for the benefit of those who are hesitant about prescribing biosimilars. The meeting took place at the largest hospital and medical school in Austria, the General Hospital Vienna, and provided information about the registration and authorisation processes and the mandatory comparability testing against the reference product. Many new biosimilars are likely to be authorised and made available soon, following tests for safety and efficacy via the centralised procedure, leading to upright authorisations in all 27 EU-Member States. As common reluctance to use biosimilars is mainly based on lack of information, this session was an opportunity to answer as many questions as possible.

One major issue was the automatic substitution with biosimilars. Representing the Austrian Regulatory Authority I explained that it is currently not advised that pharmacists automatically substitute a reference product with a biosimilar. Rather, the European Medicines Agency (EMA) states that the decision to use a biosimilar should always involve a well-informed physician.

In the US, automatic substitution with biosimilars is at least a theoretical possibility, owing to a specific, step-wise approval process which first requires biosimilarity to be shown and then interchangeability. In contrast, EMA does not take responsibility for decisions on interchangeability and/or substitution. Instead, it is for the national competent authorities of EU-Member States to decide based on the scientific evaluation performed by EMA. This could potentially lead to different approaches in the different Member States. However, there seems to be unanimous disapproval of the idea of automatic switching by pharmacists without the involvement of doctors.

I underscored that even by now there is a good opportunity for increasing the uptake of biosimilars in Austria by promoting their use as a starting treatment for new patients rather than by switching existing therapies to biosimilars. Austria already has a very high penetration with biosimilars, ranking third in the EU in 2011, with a defined daily dose of 0.09 per population head. In the case of generics, research by the social insurance system had shown that merely starting new patients on treatment with generics could have a marked effect on raising the penetration rate. Similar effects can be expected for biosimilars.

Hearing that they would remain directly involved in decisions over treatment with a biosimilar seemed to alleviate a major concern for the participating Austrian physicians [1]. However, they will be obliged to choose biosimilars more often in order to save a huge amount of money for the public health system. Mag Jutta Piessnegger of the Austrian Main Association of Social Health Insurance explained that biosimilars will be priced in Austria in the same way generics are priced, meaning that in a complex system of price reductions, after biosimilar market entry, biosimilars must be priced at 48 to 60 per cent below the cost of the originator, allowing room for substantial savings.

The Austrian Regulatory Authority is interested in continuing to cooperate and seek to have further dialogue with Austrian physicians so that they can make well-informed decisions regarding biosimilar use [2].

Competing interests: None.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned, internally peer reviewed.

References

1. Clayton J. The potential for doctors to contribute to biosimilar guidelines. Generics and Biosimilars Initiative Journal (GaBI Journal). 2012;1(3-4):152. doi:10.5639/gabij.2012.0103-4.039

2. GaBI Online – Generics and Biosimilars Initiative. Dialogue needed to build confidence in biosimilars [www.gabionline.net]. Mol, Belgium: Pro Pharma Communications International; [cited 2012 Dec 3]. Available from: www.gabionline.net/Biosimilars/Research/Dialogue-needed-to-build-confidence-in-biosimilars

|

Author: Christoph Baumgärtel, MD, Department Head, Department Safety and Effi cacy Assessment of Medicinal Products, Institute Marketing Authorisation of Medicinal Products & LCM, AGES PharmMed–Austrian Medicines and Medical Devices Agency, and Austrian Federal Offi ce for Safety in Health Care, European Expert in Pharmacokinetics Working Party and Safety Working Party of EMA, Member of Austrian Prescription Commission, 5 Traisengasse, AT-1200 Vienna, Austria |

Disclosure of Conflict of Interest Statement is available upon request.

Copyright © 2013 Pro Pharma Communications International

Permission granted to reproduce for personal and non-commercial use only. All other reproduction, copy or reprinting of all or part of any ‘Content’ found on this website is strictly prohibited without the prior consent of the publisher. Contact the publisher to obtain permission before redistributing.

Related articles

The potential of generics policies: more room for exploitation–PPRI Conference Report

Statin generics: no differences in efficacy after switching

What lessons can be learned from the launch of generic clopidogrel?

Source URL: https://gabi-journal.net/austria-increases-dialogue-in-order-to-involve-physicians-more-with-biosimilars.html

A recent study by IMS Health Austria (IMS) revealed that in Austria healthcare payers could have saved more than a quarter billion Euros during 2011 if physicians would have prescribed more generics to their patients.

The total reimbursed medicines market in Austria totals Euros 1.89 billion. IMS estimates that 89% of the total market by volume is theoretically replaceable by generics. However, of the total more than 7 million counting units (CU : dosages per day) prescribed in 2011 only 38% were replaced by generics (2.7 million CU).

IMS considered that the average price of an originator drug is at least three Euros 3 more expensive than the average generic drug, meaning that an average generic drug CU costs Euros 0.13 whereas an originator with a price of Euros 0.20 per CU is at least 54% more expensive. If every originator in the replaceable segment were switched to a generic drug, the country would reap savings of more than 3.6 million CU that would result in Euros 256 million in savings per year. This value is however only theoretical as it would mean a 100% generics penetration rate in the replaceable segment.

Since in Austria physicians are only advised, but not obliged, to prescribe generics; and pharmacists are also not obliged to substitute an originator by a generic drug as is common practice in other countries, e.g. Germany with its ‘aut-idem’ system, such penetration rates are just wishful thinking. In fact, at the moment Austria is at the lower end regarding generics penetration. According to 2010 data from IMS, generics in Austria had a market share of only 26% of the total retail market, visit the article link below to view the data on generics uptake rates in Europe.

The Austrian Generics Association (Österreichische Generikaverband) and the Austrian Medicines Authority indeed think that it may be possible to increase the generics share up to 60% during the next years. These opinions, along with the size of the potential savings in Austria, have led to huge media and television coverage in Austria. One crucial point however will remain – providing information to and convincing both physicians and patients of the safety and quality of generics.

Christoph Baumgärtel, MD

Member of International Editorial Advisory Board, GaBI Journal

Disclosure of Conflict of Interest Statement is available upon request.

Permission granted to reproduce for personal and non-commercial use only. All other reproduction, copy or reprinting of all or part of any ‘Content’ found on this website is strictly prohibited without the prior consent of the publisher. Contact the publisher to obtain permission before redistributing.

Source URL: https://gabi-journal.net/austria-could-save-euros-256-million-by-using-more-generics.html

|

Abstract: |

Submitted: 27 July 2012; Revised: 3 September 2012; Accepted: 3 September 2012; Published online first: 5 September 2012

A notable abstract on generics substitution of statins was presented at the 2010 Congress of the European Society of Cardiology [1]. Some of the resulting media coverage was equally interesting, stating, for example, that ‘Patients should stay on Pfizer’s Lipitor, and not switch to generics’ [2]. What the abstract predicted was an increased potential risk for serious cardiovascular events following a switch to generic statins. Despite this interesting finding, the question of whether generic statins should be considered inferior to the atorvastatin brand leader, however, can be answered with a resounding ‘No’.

Nonetheless, what may appear initially to be a paradoxical conclusion makes perfect sense when considering that the study’s aim was not to see if generics act differently to branded products. Instead, the study showed that following a government-mandated switch to generic statins in The Netherlands, doctors–intentionally or unintentionally–prescribed inadequate doses of the generic drug when switching. Notably, the Dutch doctors were not prescribing generics with the identical active pharmaceutical substance, but instead were switching from branded atorvastatin (Sortis/Lipitor) to various generic versions with simvastatin. This switch makes sense considering the high costs of originator atorvastatin and the remarkably lower costs of generic simvastatin. However, the change of active substances means that it was not a true generics switch because another active substance was prescribed. More importantly, the two active substances are not of equal potency: atorvastatin is more potent than the same molar quantity of simvastatin [3]. The dose equivalence therefore is set at a ratio of at least 1:2 to 1:4, as indicated in the product information leaflets.

Nevertheless, not all prescribing physicians are aware of this fact, and as a result, 20 mg atorvastatin is often substituted by just 20 mg simvastatin. An analysis of the Dutch database revealed, that out of 39,031 patients, more than a third (33.7%) received less than an equipotent dose of simvastatin after the switch. These figures were calculated under the assumption of a potency ratio of 1:2. If the authors had used a ratio of 1:4, the numbers would have been even higher. Statistical models suggested that this inadequate dosing would lead to a 5.6% increase in LDL-cholesterol levels. This, together with the findings of a meta-regression study [4] showing that every 25 mg/dL (0.65 mmol/L) reduction in LDL-cholesterol lowers the risk of serious cardiovascular events by 14%, indicates that inadequate simvastatin dosing might increase cardiovascular risk by at least 5.5% [1].

It remains uncertain whether these dose reductions were intentional or not. But an intentional dose reduction is unlikely due to the high numbers of patients involved, which does not reflect everyday clinical practice. Worryingly, our conclusion is that a substantial number of switches in The Netherlands were performed by physicians who were unaware of the different potencies of statins. This occurred after a government-mandated change in policy in which physicians would have to justify their prescriptions of branded statins. The result was an economically beneficial increased switch to generics. At the time of the policy change, however, atorvastatin generics were not yet licensed, and so patients were switched to generic simvastatin instead as the available alternative.

Fortunately, this situation has not occurred in Austria, for example. Here, the guideline for economic prescribing [5] stipulates that in the case of two equally effective treatments the cheaper one should be chosen. To do so, Austrian doctors can access an online ‘Info-tool’ [6] which indicates alternatives to an originator product and their prices. This tool takes the potency difference of statins into account correctly. A search for alternatives to atorvastatin, e.g. to Sortis 20 mg tablets, produces a list of several simvastatin generics, all at an appropriate dosage form of 80 mg tablets, some of them even with a score line. This takes into account dose equivalence in the range of 1:2 to 1:4. The product information leaflets affirm the difference in potency: the indicated dosage of atorvastatin for the prevention of cardiovascular disease is 10 mg per day, while for simvastatin it is 20–40 mg per day.

The Dutch study shows the importance of thoroughly checking product information and using additional info-tools. The erroneous switch to less than equivalent doses of simvastatin, two to four times below the recommended dosage, could have been detected and presumably avoided if the prescribing physicians had consulted these resources properly.

In conclusion, the media coverage that generic statins might be inferior per se, and that switching should be avoided, can be refuted. In support of this, a Korean study [7] examined the efficacy of atorvastatin generics to reduce LDL-cholesterol and total cholesterol compared to its atorvastatin originator. Reduction after eight weeks from baseline for LDL-cholesterol was about 44% for the generics and 46% for the originator, showing no significant difference. Corresponding values for total cholesterol were about 30% and 31%, respectively, and not significantly different. In addition, a Slovenian trial [8] similarly revealed that generic atorvastatin leads to an equal reduction in LDL-cholesterol compared to the originator after 12 weeks (37.8% vs 38.4%, p = ns). Both drugs reduced the absolute coronary risk by 13% and 13.3% for the generic and reference atorvastatin, respectively.

These findings are important as a number of atorvastatin generics have recently entered the market that will increasingly be prescribed in future, as was already seen with other drug substances [9, 10], giving assurance to physicians that atorvastatin generics are equally as safe and effective as the originator. Physicians who choose to switch from atorvastatin to simvastatin may do so, but must consider the different potency of these two statins and take care to prescribe the correctly adjusted dose.

A misunderstood study about the statin drug Lipitor and its generic alternatives caused a media storm, with the notion that generics were inferior. A closer examination, however, reveals that physicians had mistakenly prescribed inadequate doses of the generic drug alternatives, putting patients at higher risk of cardiovascular disease.

Competing interests: None.

Provenance and peer review: Commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

1. Liew D, et al. The cardiovascular consequences of switching from atorvastatin to generic simvastatin in the Netherlands. Abstract n° 3562. ESC; 2010 Aug 28–Sep 1; Stockholm, Sweden.

2. Bloomberg News, 2010-08-20 [homepage on the Internet]. Patients should stay on Pfizer’s Lipitor, not switch to generic, study say. [cited 2012 Sep 3]. Available from: www.bloomberg.com/news/2010-08-20/cholesterol-drug-study-shows-heart-risks-in-switch-to-generic-from-lipitor.html

3. Rogers, et al. A dose-specific meta-analysis of lipid changes in randomized controlled trials of atorvastatin and simvastatins. Clin Ther. 2007 Feb; 29(2):242-52.

4. Delahoy PJ, et al. The relationship between reduction in low-density lipoprotein cholesterol by statins and reduction in risk of cardiovascular outcomes: an updated meta-analysis, Clin Ther. 2009 Feb;31(2):236-44.

5. Hauptverband der österreichischen Sozialversicherungsträger [homepage on the Internet]. [Austrian instructions on economic prescribing of medicines (RÖV)]. [cited 2012 Sep 3] German. Available from: www.hauptverband.at/portal27/portal/hvbportal/channel_content/cmsWindow?action=2&p_menuid=58307&p_tabid=4

6. Hauptverband der österreichischen Sozialversicherungsträger [homepage on the Internet]. [Infotool to the Austrian Reimbursement-Code]. [cited 2012 Sep 3] German. Available from: www.hauptverband.at/portal27/portal/hvbportal/emed/

7. Kim SH, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of a generic and a branded formulation of atorvastatin 20 mg/d in hypercholesterolemic Korean adults at high risk for cardiovascular disease: a multicenter, prospective, randomized, double-blind, double-dummy clinical trial. Clin Ther. 2010 Oct;32(11):1896-905.

8. Boh M, et al. Therapeutic equivalence of the generic and the reference atorvastatin in patients with increased coronary risk. Int Angiol. 2011 Aug;30(4):366-74.

9. Baumgartel C, Godman B, Malmstrom R, et al. What lessons can be learned from the launch of generic clopidogrel? Generics and Biosimilars Initiative Journal (GaBI Journal). 2012;1(2):58-68. doi:10.5639/gabij.2012.0102.016

10. Baumgartel C. Generic clopidogrel–the medicines agency’s perspective. Generics and Biosimilars Initiative Journal (GaBI Journal). 2012;1(2):89-91. doi:10.5639/gabij.2012.0102.019

|

Author: Christoph Baumgärtel, MD, Department Head, Department Safety and Efficacy Assessment of Medicinal Products, Institute Marketing Authorisation of Medicinal Products & LCM, AGES PharmMed–Austrian Medicines and Medical Devices Agency, and Austrian Federal Office for Safety in Health Care, European Expert in Pharmacokinetics Working Party and Safety Working Party of EMA, Member of Austrian Prescription Commission, 5 Traisengasse, AT-1200 Vienna, Austria |

Disclosure of Conflict of Interest Statement is available upon request.

Permission granted to reproduce for personal and non-commercial use only. All other reproduction, copy or reprinting of all or part of any ‘Content’ found on this website is strictly prohibited without the prior consent of the publisher. Contact the publisher to obtain permission before redistributing.

Source URL: https://gabi-journal.net/statin-generics-no-differences-in-efficacy-after-switching.html

Author byline as per print journal: Christoph Baumgärtel1, MD; Brian Godman2,3,4, BSc, PhD; Rickard E Malmstrom5, MD, PhD; Morten Andersen6, MD, PhD; Mohammed Abuelkhair7, PharmD; Shajahan Abdu7, MD; Marion Bennie8,9, MSc; Iain Bishop9, BSc; Thomas Burkhardt10, MSc; Sahar Fahmy7, PhD; Jurij Furst11; Kristina Garuoliene12, MD, PhD; Harald Herholz13, MPH; Marija Kalaba14, MD, MHM; Hanna Koskinen15, PhD; Ott Laius16, MScPharm; Julie Lonsdale17, BSc; Kamila Malinowska18, MD; Anne M Ringerud19, MScPharm; Ulrich Schwabe20, MD, PhD; Catherine Sermet21, MD; Peter Skiold22, MSc, PhD; Ines Teixeira23, BA, MSc; Menno van Woerkom24, MSc; Agnes Vitry25, PharmD, PhD; Luka Vončina26, MD, MSc; Corrine Zara27, PharmD; Professor Lars L Gustafsson4, MD, PhD

|

Introduction and study objectives: Resource pressures will continue to grow. Consequently, health authorities and health insurance agencies need to take full advantage of the availability of generics in order to continue funding comprehensive health care particularly in Europe. Generic clopidogrel provides such an opportunity in view of appreciable worldwide sales of the originator. However, early formulations contained different salts and only limited indications. Consequently, there is a need to assess responses by the authorities to the early availability of generic clopidogrel including potential reasons preventing them from taking full advantage of the situation. In addition, it is necessary to determine the extent of initial price reductions obtained in practice to guide future activities. |

Submitted: 13 September 2011; Revised manuscript received: 2 December 2011; Accepted: 5 March 2012

There is increasing focus on pharmaceutical expenditure globally [1], driven by factors including changing demographics and the continued launch of new premium priced medicines [1–7]. This has stimulated a number of initiatives surrounding generics, with European countries learning from each other as they continually search for additional measures to further enhance prescribing efficiency [1, 3, 4, 6, 7]. Initiatives include measures to enhance the utilisation of generics versus originators and patent protected products in the class or related class, as well as measures to obtain low prices for generics [1, 3, 4, 6–8]. This includes generic clopidogrel, with global sales of the originator at US$9.8 billon in 2009 and US$9.7 billion in 2010 [9, 10]. However, there have been concerns with different salts and indications between the originator and early generic clopidogrel formulations, which could reduce potential health authority and health insurance agency savings from the availability of generic clopidogrel. In addition in the US, the originator manufacturer also instigated a range of activities to delay the entry of generic clopidogrel. These included a recent successful and prolonged legal battle against a Canadian generics manufacturer [11, 12].

These issues regarding generic clopidogrel have arisen because manufacturers have been able to address the technicalities of Plavix’s European patent protection early by producing clopidogrel in a different salt, such as the besylate salt, and initially, only launching for secondary prevention of atherosclerotic events post myocardial infarction or post ischaemic stroke, i.e. without the acute coronary syndrome (ACS) indication [11, 13, 14].

The Swiss generics company Acino has been able to market its generic clopidogrel in Germany since August 2008. By the end of 2008, Acino’s generic clopidogrel accounted for approximately one quarter of total clopidogrel utilisation [13, 14]. Other generics versions were also launched in Austria in 2008. However, it was not until mid 2009 that EMA was able to approve various generic clopidogrel preparations through its centralised procedure [11, 13, 14]. This included more than 20 generic clopidogrel products, which contained the besilate and hydrogen sulphate salts, of which eight were approved for both indications, i.e. both secondary prevention and ACS indications [15]. However, in the UK for instance, initial generics typically only included the secondary prevention indication in their submissions [15, 16].

Health authority or health insurance agencies faced similar issues to drug licensing authorities when considering reimbursement and/or recommending the prescribing of generic clopidogrel versus the originator potentially impacting on outcomes. These included whether changing the salt would alter the rate of absorption, toxicity and stability of the active drug. In addition, efficacy questions were raised by the fact that bioequivalence studies measured only the parent compound or inactive metabolite rather than the low and transient concentrations of the active metabolite, present only briefly after dosing, as well as possible concerns with inter-patient variability [17–22]. There have also been concerns among some authorities that any putative interaction between clopidogrel and proton pump inhibitors will be less well known initially for the generic salts. These concerns were in addition to patent issues in each European country, the latter leading to widely different dates when generics become available for prescribing [3, 4]. Additionally, there have been issues regarding the functional integrity of CYP2C19 in patients as this could potentially affect the availability of the clopidogrel and hence outcomes in practice [23, 24]. As such, personalised medicine using tailored individualised antiplatelet treatment based on pharmacogenetic testing could be helpful in identifying which patients should be treated with clopidogrel and which with newer drugs such as prasugrel and ticagrelor. However, other studies have questioned this [25–29]. In any event, this should not impact on the debate of whether generic or originator clopidogrel should be prescribed. Of potential greater importance is the widely different timescales that currently exists among European countries when authorising reimbursement for generics [13, 30].

The situation for health authorities and health insurance agencies was further complicated by the EMA recall in March 2010 of clopidogrel besylate produced by Glochem Industry Ltd’s manufacturing facility in India [31–34]. The medicines concerned included Clopidogrel 1A Pharma, Clopidogrel Acino, Clopidogrel Acino Pharma, Clopidogrel Acino Pharma GmbH, Clopidogrel Hexal, Clopidogrel Ratiopharm, Clopidogrel Ratiopharm GmbH and Clopidogrel Sandoz. The marketing authorisation holder of all these products was Acino Pharma GmbH [31–34], which held the market authorisation for the majority of early generics formulations. However, Acino and other companies have been able to source generic clopidogrel from other companies to overcome possible supply problems, with multiple companies and formulations now typically available across Europe. The originator manufacturer tried to take advantage of these recalls through pointing out the known quality of Plavix [35]. The impact of this approach though was reduced in reality by EMA approval of a number of generic clopidogrel formulations from different manufacturers. In addition, European health authorities and health insurance companies are continually seeking ways to fund new premium priced drugs and increased drug volumes from ageing populations within finite resources through encouraging greater generics utilisation, Table 1 as well as references 1 and 36 contain examples of different authority approaches across Europe to enhance generics utilisation with similar approaches among managed care organisations in the US [1–4, 5–8, 36].

Consequently, the principal objective of this paper is to document health authority and health insurance agency responses to take advantage of the early availability of generic clopidogrel products. Secondly, to assess potential reasons preventing health authorities and health insurance agencies from taking full advantage of the early availability of generic clopidogrel, and potential ways to address this in the future. Finally, to determine the extent of price reductions that have been obtained by a range of countries for generic clopidogrel versus pre-patent loss originator prices in the initial months following generics availability. This aims to provide knowledge of how the future availability of generics in high expenditure areas can be accelerated, combined with measures to enhance their rapid uptake versus originators, to rapidly release valuable resources.

We first performed a literature review of English language papers in PubMed, MEDLINE and Embase between 2005 and April 2011 using the keywords ‘generic clopidogrel’. But because this resulted in only a limited number of publications, e.g. only seven relevant English language papers were cited in PubMed, the literature search was supplemented by additional information, papers and web-based articles known to the many co-authors from health authorities, health insurance agencies and their advisers from across Australia, Europe and the Middle East regarding generic clopidogrel. This information was subsequently re-confirmed with each co-author by the lead co-author Dr Brian Godman to ensure the accuracy of the data provided, hence its robustness. This is an accepted technique where there is limited information publically available to achieve study aims [2–4, 6, 7, 37–42]. No attempt was made to review the quality of the published studies using the methodology of the Cochrane Collaboration [43] in view of the paucity of peer-reviewed published studies.

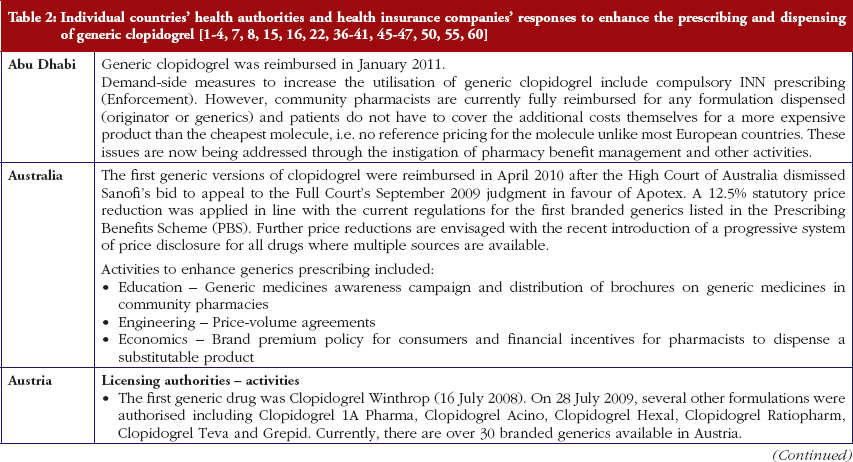

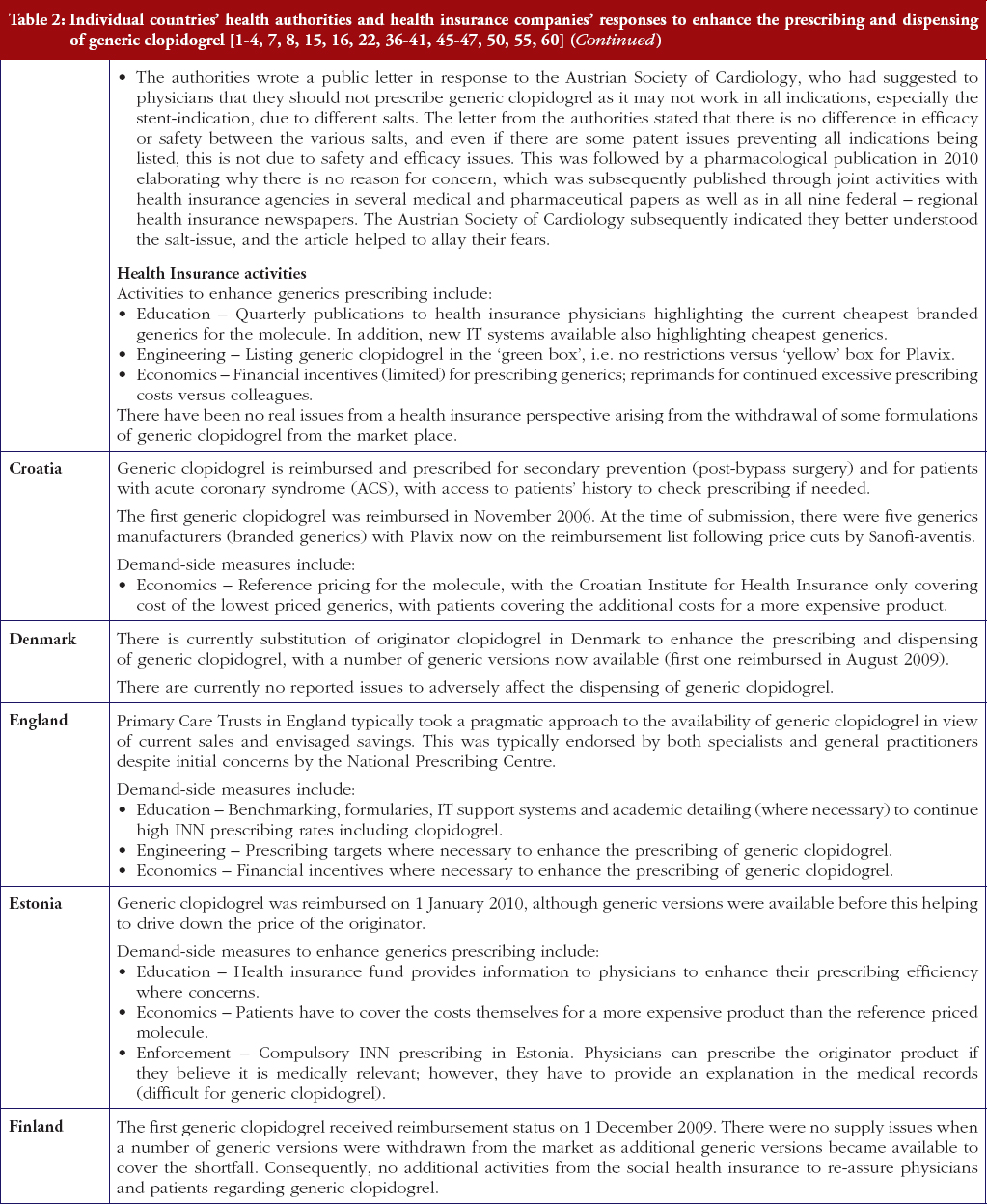

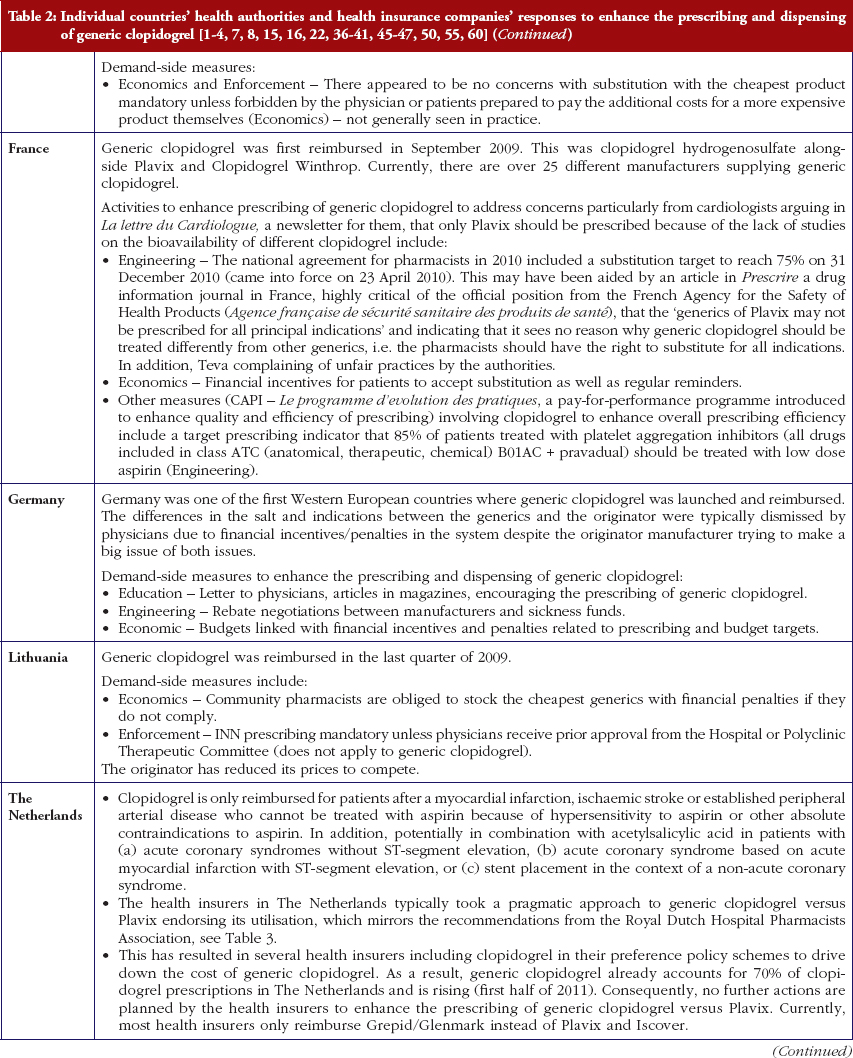

Reimbursed prices for generic clopidogrel were either provided directly from the co-authors from their own internal sources based on the 75 mg tablet (Personal communications from: Mr Iain Bishop, Mr Thomas Burkhardt, Dr Jurij Furst, Dr Kristina Garuoliene, Dr Hanna Koskinen, Mr Ott Laius, Dr Catherine Sermet, Dr Peter Skiöld, Professor Ulrich Schwabe, Dr Agnes Vitry); alternatively from administrative databases (Republic of Serbia’s Health Insurance Fund database, Dr Marija Kalaba). The findings were again validated with pertinent co-authors to ensure accuracy. Data from administrative databases included reimbursed expenditure/defined daily dose (DDD)–with DDDs defined as ‘the average maintenance dose of the drug when used on its major indication in adults’ [44]–for both the originator and generics. This approach has been successfully used in previous publications when reviewing the impact of ongoing reforms to reduce generics prices versus originators to enhance future prescribing efficiency in Europe [2–4, 6, 7, 37–40]. The countries reviewed were selected based on their different geographies, financial base for the healthcare system (taxation or insurance based) and population size to enable comprehensive comparisons of payer activities as well as reimbursed prices to provide examples to others. In addition in some countries, generic clopidogrel has only recently been reimbursed, see Table 2.

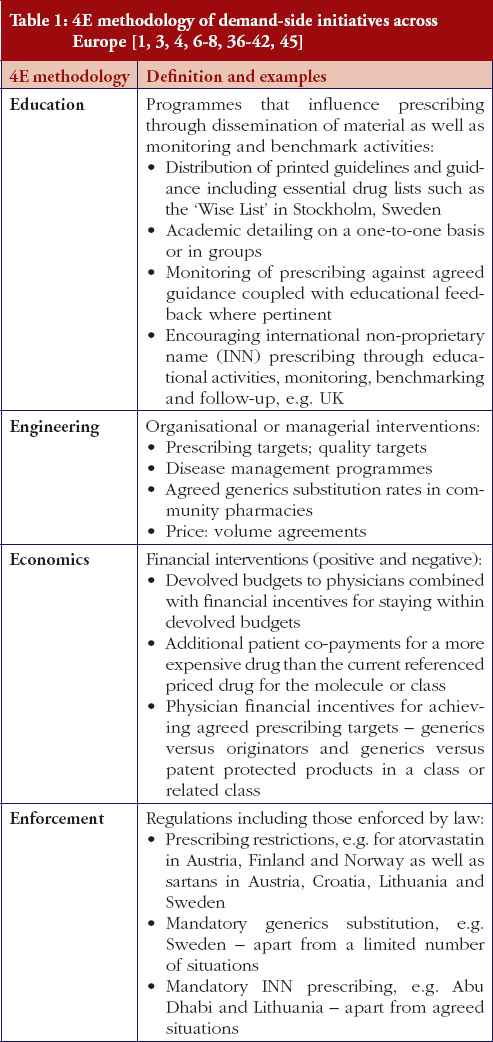

The demand-side measures initiated in each selected country to enhance the utilisation of generic clopidogrel have been taken from published sources supplemented with additional information from the co-authors. The latter approach providing most data in view of, as stated, limited available information in the public domain. Demand-side activities were again checked with pertinent co-authors to ensure the accuracy of the information provided. The various demand-side measures were subsequently collated using the 4E methodology, i.e. education, engineering, economics and enforcement, to simplify comparisons between countries, see Table 1. This approach has been successfully used in other settings to compare and contrast the influence of different demand-side interventions in practice [3, 4, 6, 38–40].

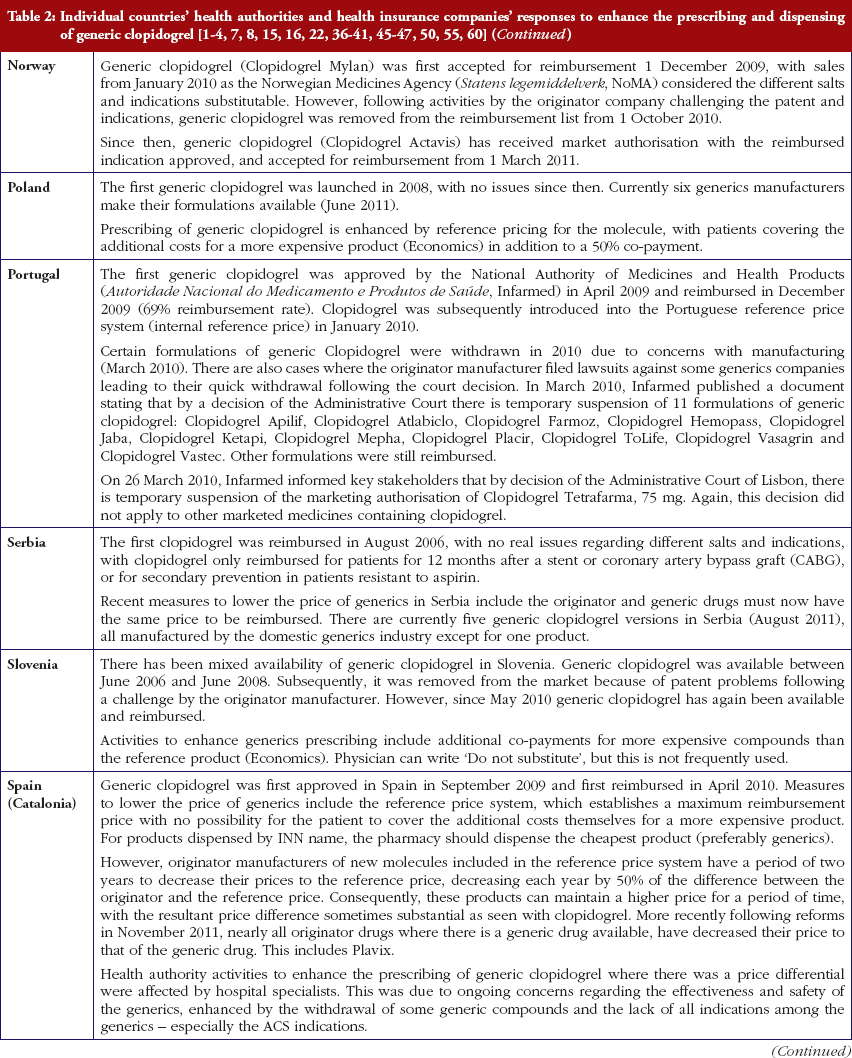

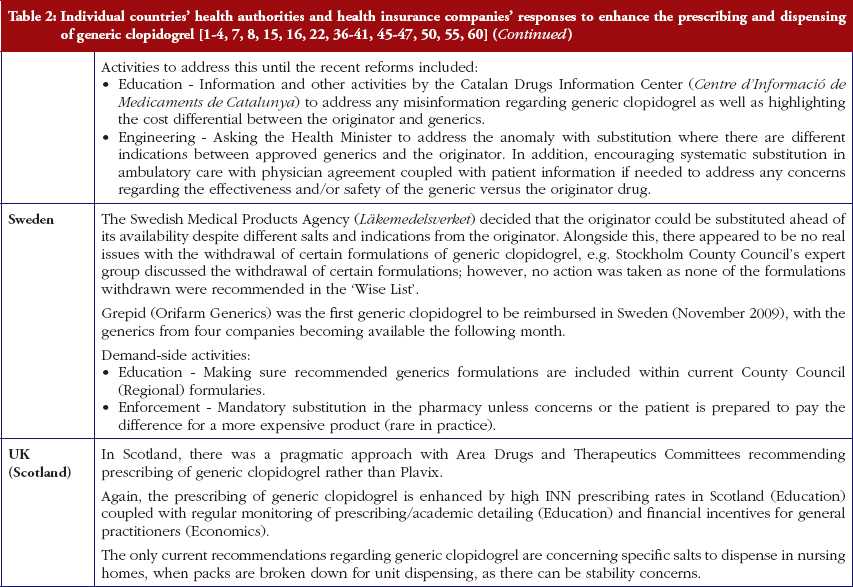

Most health authorities and insurers have adopted a pragmatic approach towards differences in the salt and indications between the generic and the originator drug to enhance the prescribing of generic clopidogrel, see Table 2; with examples of pragmatic approaches documented in Table 3. However, this has not always been possible. For example, activities in Norway, Portugal and Slovenia have resulted in all or some versions of generic clopidogrel being removed from the market place for a period of time, see Table 2.

There has also been extensive education of physicians in some European countries to allay their fears about prescribing generic clopidogrel with different salts and indications, see Table 2. As a result, utilisation of generic clopidogrel has been enhanced thereby helping health authorities and health insurance agencies gain savings from the early availability of generic clopidogrel given the global expenditure on Plavix pre-patent loss [9, 10].

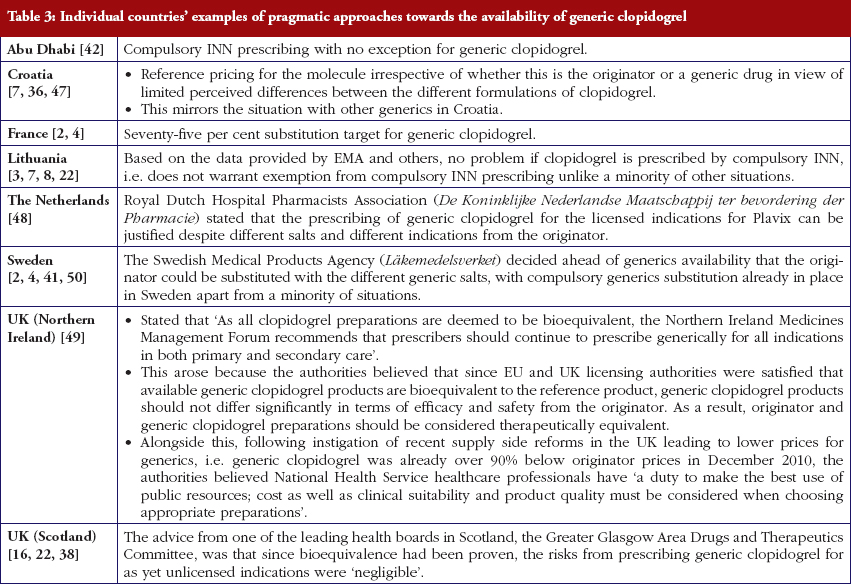

The various measures instigated among countries to obtain low price of generics [2, 4] has already resulted in appreciable price reductions in some countries. However, this was not universal with a 20-fold difference in reimbursed prices existing between countries in April to July 2011, see Table 4.

Health authorities and health insurance agencies have typically adopted a pragmatic approach to enhance the prescribing and dispensing of generic clopidogrel once available. As a result, valuable resources have been released from the early availability of generic clopidogrel. This is despite different salts and more limited indications initially versus the originator, coupled with the withdrawal of some formulations of generic clopidogrel from the market place due to manufacturing concerns.

Activities undertaken by health authorities and health insurance agencies to enhance the prescribing of generic clopidogrel, see Table 2, mirror those undertaken for other generics [2–4, 6, 7, 37–40]. They also included extensive education among key stakeholder groups in some countries to enable health authorities and health insurance agencies to fully realise the finan-cial benefits from the early availability of generic clopidogrel. However, activities in some countries have not always been possible following successful challenges to the availability of generic clopidogrel, which led to the removal of all or some formulations for a period of time, see Table 2.

It may well be in the long term that compliance is a greater issue to maximise outcomes from clopidogrel than any perceived differences in bioavailability between formulations, mirroring the situation with other cardiovascular drugs [51]. Consequently, some of the resources released from the availability of generic clopidogrel could be used to address this issue to maximise the health gain from clopidogrel alone or in combination with aspirin among pertinent patients.

Alongside this, recent studies [61, 62] have further questioned the clinical utility of measuring CYP2C19 endorsing our earlier comments that this measurement should not impact on the debate of whether to prescribe generic or originator clopidogrel.

There was already considerable variation in reimbursed prices for generic clopidogrel versus the originator, see Table 4, mirroring the findings in other studies [2, 3, 4, 6]. Again the size of the country’s population does not appear to be responsible for these differences, confirming previous publications [37]. Price reductions appear to be determined largely by ongoing policies to enhance generics utilisation [1–4, 52]. It is likely though that in time reimbursed prices for clopidogrel will converge, driven largely by countries striving to release further resources from the increasing availability of generics [53]. This will be researched in future studies alongside the impact of the various policies in each country to enhance the prescribing of generic clopidogrel versus the originator, see Table 2.

In conclusion, payers across Europe are learning from each other how best to take full advantage of the early availability of generics, even when there are different salts and indications, to maximise the use of available resources. This will continue. However, as we have seen this is not always possible. We believe pharmaceutical companies should accept generics availability to enable continued funding of new premium priced products, and not try to delay their introduction through challenging reimbursement decisions. The alternative, as resource pressures continue growing, is limited or no funding for new drugs, which is not in the future interests of all key stakeholder groups [1–4, 8, 54].

Pharmaceutical expenditure is typically the largest or equalling the largest component of expenditure in ambulatory, i.e. non-hospital, care. Consequently, the increasing availability of multiple sourced products (generics) once a product loses its patent is welcomed by health authorities and health insurance agencies as these can be provided at considerably lower costs than the originator. This is the case with generic clopidogrel with its price already only 12% of the cost of the originator within a few months in some European countries, with prices expected to fall further.

However, there can be concerns among physicians and patients with the effectiveness of a generic drug if this is provided as a different salt to the originator. The availability, and hence effectiveness of a generic drug, is tested though by the European authorities before such medications can become available to help address such fears. In this case, the European authorities found no bioavailability problems with different salts of generic clopidogrel compared to the originator substance. The European authorities go on testing generics to ensure trust in the system, and will remove generics if there are justified concerns. This happened with some of the manufacturers of generic clopidogrel giving further confidence in the system.

Health authorities and health insurance companies across Europe also typically found no issue with early formulations of generic clopidogrel despite different salts indications than the originator drug. Consequently, they typically took a pragmatic approach to encourage physicians to prescribe generic clopidogrel versus the originator to release considerable monies. Patients can also play their part by accepting generics that have been approved by the European authorities rather than the originators, with the monies released used to help maintain the European ideals of comprehensive and equitable health care in these difficult economic times especially in Europe.

The majority of the authors are employed directly by health authorities or health insurance agencies or are advisers to these organisations. No author has any other relevant affiliation or financial involvement with any organisation or entity with a financial interest in, or financial conflict with, the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript.

The study was in part supported by grants from the Karolinska Institutet and the Swedish Reimbursement Agency. We thank Ms Margaret Ewan from HAI Global for her help with reimbursed prices in New Zealand.

No writing assistance was utilised in the production of this manuscript.

Provenance and peer review: Commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

1Austrian Medicines and Medical Devices Agency, 9 Schnirchgasse, AT-1030 Wien, Austria

2 Institute for Pharmacological Research Mario Negri, 19 Via Giuseppe La Masa, IT-20156 Milan, Italy

3 Prescribing Research Group, University of Liverpool Management School, Chatham Street, Liverpool L69 7ZH, UK

4 Department of Laboratory Medicine, Division of Clinical Pharmacology, Karolinska Institutet, Karolinska University Hospital Huddinge, SE-14186, Stockholm, Sweden

5 Department of Medicine Solna, Division of Clinical Pharmacology, Karolinska Institutet, Karolinska University Hospital Solna, SE-17176, Stockholm, Sweden

6 Centre for Pharmacoepidemiology, Karolinska Institute, Karolinska University Hospital, Stockholm, Solna, Sweden

7 Drugs and Medical Products Regulation, Health Authority Abu Dhabi (HAAD), PO Box 5674, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates

8 Strathclyde Institute for Pharmacy and Biomedical Sciences, University of Strathclyde, Glasgow, UK

9 Information Services Division, NHS National Services Scotland, 1 South Gyle Crescent, Edinburgh EH12 9EB, UK

10 Hauptverband der Österreichischen Sozialversicherungsträger, 21 Kundmanngasse, AT-1031 Wien, Austria

11 Health Insurance Institute, 24 Miklosiceva, SI-1507 Ljubljana, Slovenia

12 Medicines Reimbursement Department, National Health Insurance Fund, 147 Kalvarijų Str, LT-08221 Vilnius, Lithuania

13 Kassenärztliche Vereinigung Hessen, 15 Georg Voigt Strasse, DE-60325 Frankfurt am Main, Germany

14 Republic Institute for Health Insurance, 2 Jovana Marinovica, 11000 Belgrade, Serbia

15 Research Department, The Social Insurance Institution, PO Box 450, FI-00101 Helsinki, Finland

16 State Agency of Medicines, 1 Nooruse, EE-50411 Tartu, Estonia

17 Medicines Management, NHS North Lancashire, Moor Lane Mills, Moor Lane, Lancaster LA1 1QD, UK

18 HTA Consulting, 17/3 Starowiślna Str, PL-31038 Cracow, Poland

19 Norwegian Medicines Agency, 8 Sven Oftedals vei, NO-0950 Oslo, Norway

20 University of Heidelberg, Institute of Pharmacology, DE-69120 Heidelberg, Germany

21 IRDES, 10 rue Vauvenargues, FR-75018 Paris, France

22 Dental and Pharmaceuticals Benefits Agency (TLV), PO Box 22520, 7 Flemingatan, SE-10422 Stockholm, Sweden

23 CEFAR – Center for Health Evaluation & Research, National Association of Pharmacies (ANF), 1 Rua Marechal Saldanha, PT-1249-069 Lisbon, Portugal

24 Instituut voor Verantwoord Medicijngebruik, Postbus 3089, 3502 GB Utrecht, The Netherlands

25 Quality Use of Medicines and Pharmacy Research Centre, Sansom Institute, School of Pharmacy and Medical Sciences, University of South Australia, Adelaide SA 5001, Australia

26 Ministry of Health, Republic of Croatia, Ksaver 200a, Zagreb, Croatia

27 Barcelona Health Region, Catalan Health Service, 30 Esteve Terrades, ES-08023 Barcelona, Spain

References

1. Godman B, Wettermark B, Bishop I, Burkhardt T, et al. European payer initiatives to reduce prescribing costs through use of generics. Generics and Biosimilars Initiative Journal (GaBI Journal). 2012;1(1):22-7. doi:10.5639/gabij.2012.0101.007

2. Godman B, Shrank W, Wettermark B, Andersen M, et al. Use of generics – a critical cost containment measure for all healthcare professionals in Europe? Pharmaceuticals. 2010;3:2470-94. doi:10.3390/ph/3082470 ISSN 1424-8247

3. Godman B, Shrank W, Andersen M, Berg C, Bishop I, et al. Comparing policies to enhance prescribing efficiency in Europe through increasing generic utilisation: changes seen and global implications. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2010;10:707-22.

4. Godman B, Shrank W, Andersen M, Berg C, Bishop I, et al. Policies to enhance prescribing efficiency in Europe: findings and future implications. Front Pharmacol. 2011;1(141):1-16. doi:10.3389/fphar.2010.00141

5. Garattini S, Bertele V, Godman B, Haycox A, et al. Enhancing the rational use of new medicines across European healthcare systems – A position paper. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2008;64(12):1137-8.

6. Godman B, Sakshaug S, Berg C, Wettermark B, Haycox A. Combination of prescribing restrictions and policies to engineer low prices to reduce reimbursement costs. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2011;11:121-9.

7. Von ina L, Strizrep T, Godman B, Bennie M, et al. Influence of demand-side measures to enhance renin-angiotensin prescribing efficiency in Europe: implications for the future. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2011; 11:469-79.

8. Godman B, Wettermark B, Bennie M, Burkhardt T, Garuoliene K, et al. Enhancing prescribing efficiency through increased utilisation of generics at low prices. (E) Hospital 2011;13(3):28-31. Available from: myhospital.eu/journals/articles/enhanc-ing_prescribing_efficiency_through_increased_utilisation_generics_low_prices

9. Pharma Live [homepage on the Internet]. Top 500 prescription medicines. Sales Plavix 2009. [cited 2012 May 22]. Available from: www.pharmalive.com/special_reports/sample.cfm?reportID=314

10. GaBI Online – Generics and Biosimilars Initiative. 2012’s biggest patent expiries [www.gabionline.net]. Mol, Belgium: Pro Pharma Communications International; [cited 2012 May 22]. Available from: www.gabionline.net/Policies-Legislation/2012-s-biggest-patent-expiries

11. IHS Global Insight [homepage on the Internet]. Sanofi-Aventis faces new round of generic threats to plavix in Europe. [cited 2012 May 22]. Available from: www.ihsglobalinsight.com/SDA/SDADetail16688.htm

12. Shuchman M. Delaying generic competition – corporate payoffs and the future of Plavix. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1297-300.

13. Acino [homepage on the Internet]. EMEA-Committee recommends approval of Acino’s generic clopidogrel in Europe. [cited 2012 May 22]. Available from: www.acino-pharma.com/html/uploads/media/Acino_Clopi_PressRel_E_090601.pdf

14. Lisa Nainggolan. Six generic clopidogrel versions pass first EU marketing hurdle. June 2009 [cited 2012 May 22]. Available from: www.theheart.org/article/975593.do

15. PSNC [homepage on the Internet]. When generic clopidogrel available and dispensing based on salts. [cited 2012 May 22]. Available from: www.psnc.org.uk/news.php/610/clopidogrel_75mg_tablets_to_move_to_part_viii_category_a_in_December

16. NHS Greater Glasgow and Clyde [homepage on the Internet]. Postscript primary care. 2010 [cited 2012 May 22]. Available from: www.glasgowformu-lary.scot.nhs.uk/prescriber/PSPCFebruary2010.pdf

17. Pereillo JM, Maftouh M, Andrieu A, et al. Structure and stereochemistry of the active metabolite of clopidogrel. Drug Metab Dispos. 2002;30:1288-95.

18 Davies G. Changing the salt, changing the drug. Pharm J. 2001;266:322-3.