|

Introduction/Study objective: This paper aims to survey the policies implemented by European countries for pricing and promoting the use of biosimilar medicines and to explore similarities and differences with policies for generic medicines. |

Submitted: 30 March 2017; Revised: 26 May 2017; Accepted: 26 May 2017; Published online first: 9 June 2017

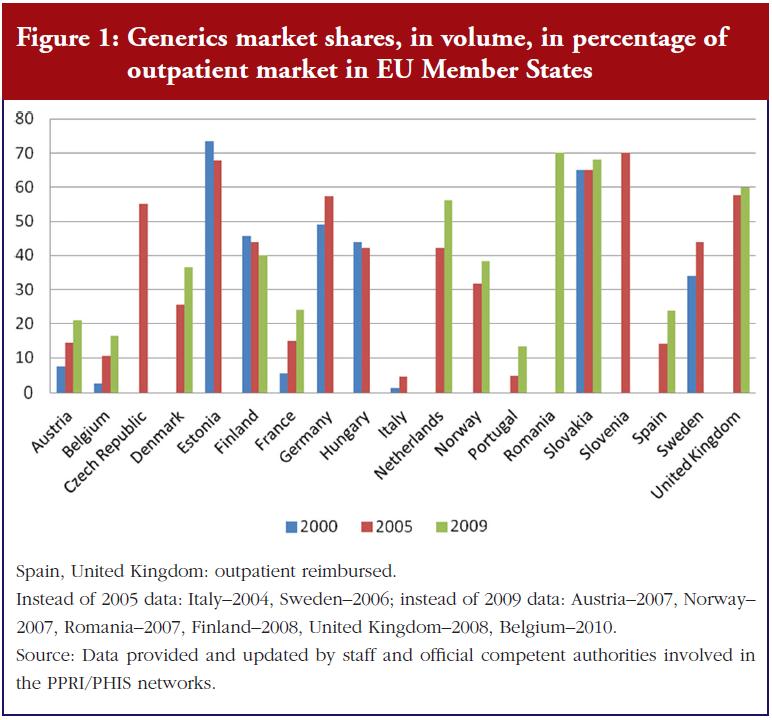

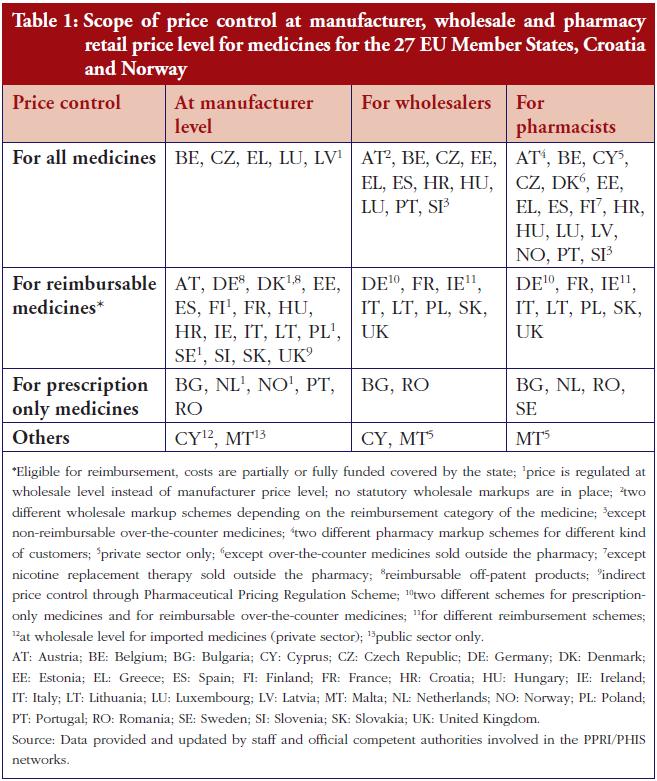

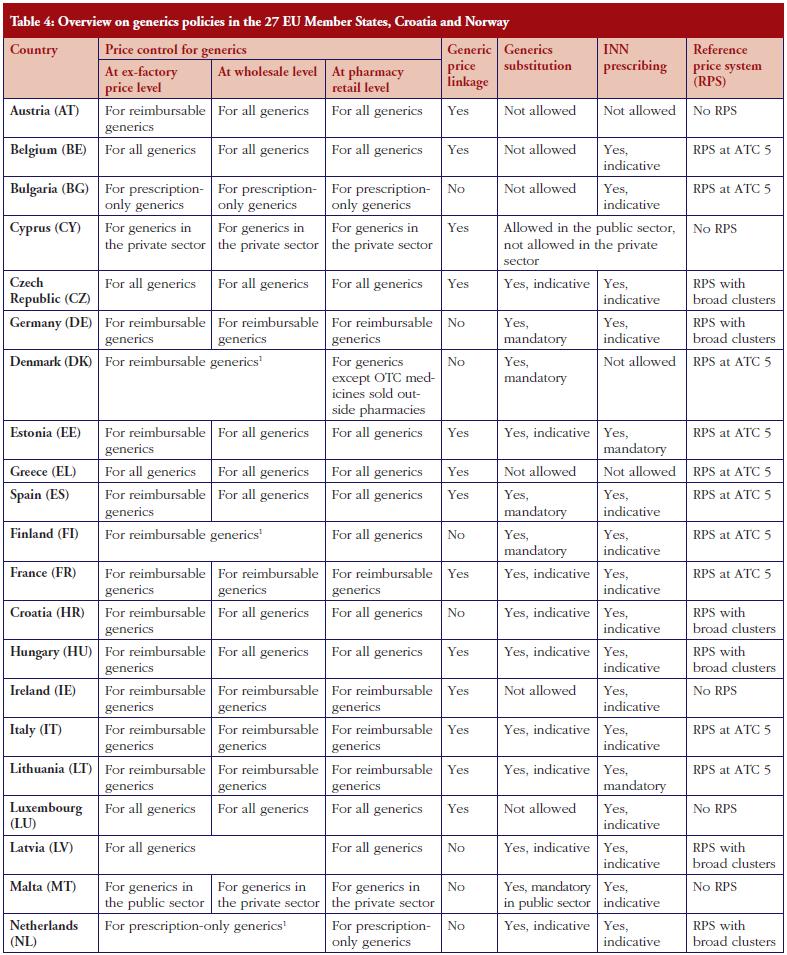

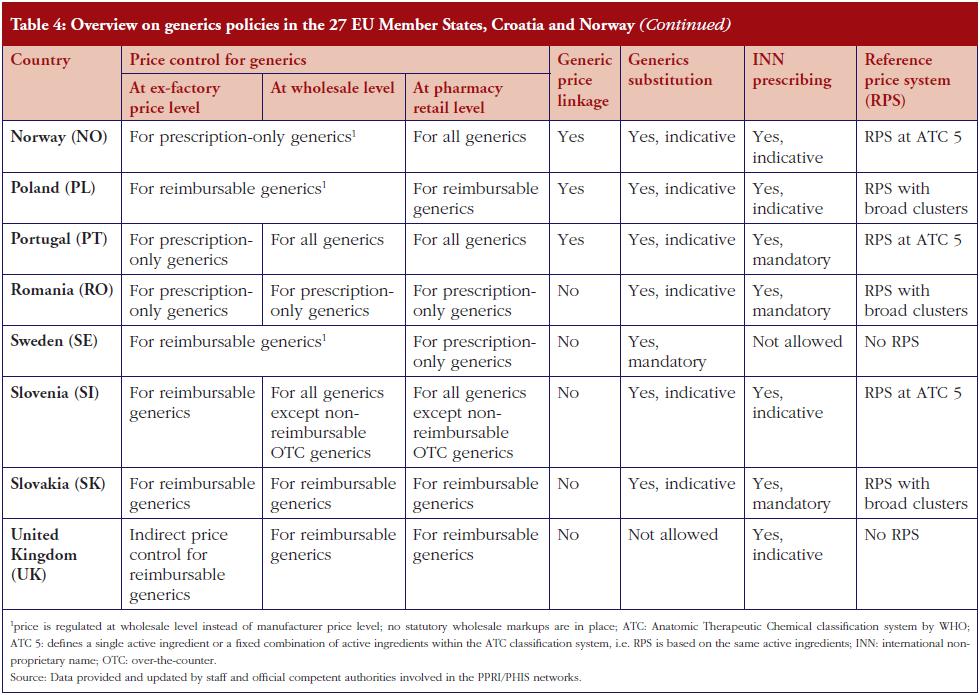

Public payers are concerned with ensuring patient access to medicines, particularly in the light of increasing pressure on budgets and the market entry of new, high-priced medicines [1]. One opportunity to generate savings and thus free resources for further investments in health is increased uptake of lower-priced medicines, such as generics. The use of generic medicines has been recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO) [2] and policymakers employ a range of supply- and demand-side tools to increase their uptake. These include generics substitution, physicians prescribing by the International Nonproprietary Name (INN) rather than the brand name, a reference price system, i.e. fixed reimbursement within a cluster of identical and similar medicines, and awareness-raising campaigns [3–9]. The ability of generics-promoting policies to reduce medicine prices and generate savings for health care has been well documented [10, 11].

Since biological medicines also significantly contribute to the pharmaceutical bill, policymakers are awaiting the entry of biosimilar medicines [12, 13], which are expected to generate substantial savings [14]. Recent years have seen several examples of tendering for biosimilar medicines successfully reducing prices [15, 16].

Under the Platform on Access to Medicines in Europe of the Corporate Social Responsibility Process, a multi-stakeholder working group was dedicated to biosimilar medicines. The working group produced a European Commission Consensus Information Document agreed by all stakeholders represented, the document provided key information about biosimilar medicines in order to foster stakeholders’ understanding of biosimilars [17]. However, the working group did not investigate which pricing and usage-enhancing policies European Union Member States applied for biosimilar medicines.

While there is good evidence of the implementation of pricing and demand-side measures for generics in Europe [3–11], the policies that European countries have been implementing to deal with biosimilar medicines are comparatively less known. To the best of the authors’ know ledge, there are few studies in the literature that provide information about pricing and demand-side policies for biosimilar medicines and the only comparative exercise performed across a large number of countries was published by the European Biopharmaceutical Enterprises in 2015 [18]. While the authors recognize the importance of this study, it did not fully explore all aspects of biosimilar medicines policies. Further studies that investigate biosimilar medicines policies are limited to a few countries [19–21] and/or to a single policy [22]. Furthermore, the findings of these studies differ.

Against this backdrop, this manuscript aims to survey the pricing and usage-enhanced policies that different countries, in particular in the European region, have implemented for biosimilar medicines, and to explore whether these policies differ from generic medicines policies.

We conducted a survey with the members of the Pharmaceutical Pricing and Reimbursement Information (PPRI) network [23]. This is a network of competent authorities for pharmaceutical pricing and reimbursement in 46 countries, thereof 43 European countries. It should be noted that European countries are those as defined by WHO [24], and thus include countries such as Israel, Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan.

We prepared questions about the status of generic and biosimilar medicines policies. We explored the pricing policies for generics and biosimilars, in particular regarding possible regulation linking the generic and/or biosimilar price to the originator price. We surveyed whether INN prescribing and substitution by generic and biosimilar medicines was permitted, and whether it was mandatory. We also aimed to identify further specific pricing policies, e.g. tendering.

While the focus of this survey was on policies for biosimilar medicines, we also aimed to survey, or validate, information on gen eric medicines policies in order to explore possible differences between policies for the two medicine groups.

As far as possible, we pre-filled the questionnaire with information available to us, through previous research and literature review. This was predominantly only possible in the field of generics. Respondents from the competent authorities were invited to provide, or validate, information on biosimilar and generic medicines policies valid in the first quarter of 2016.

We sent the survey to the PPRI network members on 7 January 2016, requesting their responses by 19 January 2016. A friendly reminder was sent before the deadline, and a further personalized reminder that was focused on key questions was sent on 11 February 2016. Preliminary results were presented and discussed during a meeting with PPRI network members on 28 April 2016, where any misunderstandings could be clarified. In response to this discussion, we created a revised version of the questionnaire, which was circulated for validation on 30 May 2016. During the survey, respondents were encouraged to reply and clarification was sought in the case of answers that raised additional questions. On 1 August 2016, the survey was officially closed and the results were shared with participants. An uncompleted version of the revised questionnaire, i.e. without pre-filled answers, is available in the Annex.

While this survey with the PPRI network was the key survey tool, where considered appropriate we added relevant information from the literature (indicated by references).

Response rate

We received responses from 36 of the 43 European PPRI members, as well as Canada and South Africa. Replies from the European region were provided by 25 of the 28 EU Member States (no data received from Ireland, Italy and Luxembourg) plus Albania, Belarus, Iceland, Israel, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Norway, Russia, Serbia, Turkey and Ukraine. Data from the missing three EU Member States and Switzerland were added, wherever possible, from literature and previous PPRI network queries on related topics. As a result, this manuscript includes information from 40 European countries, Canada and South Africa.

Pricing policies

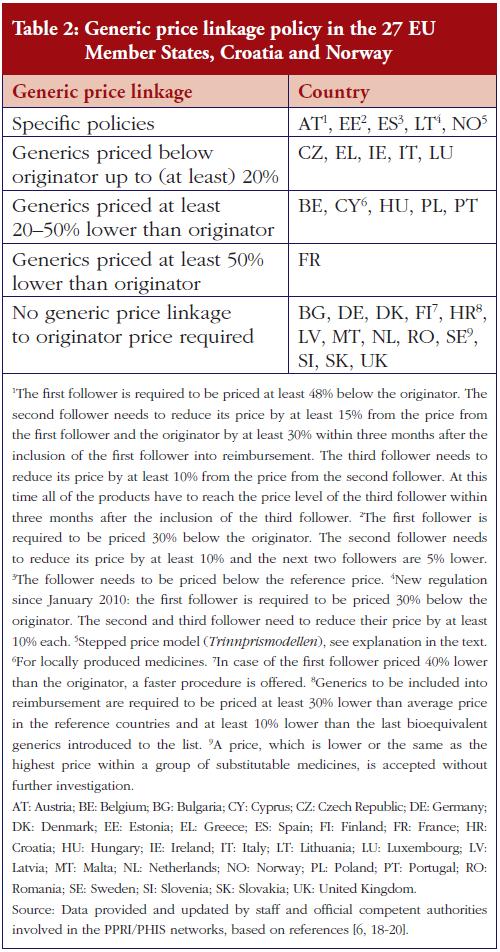

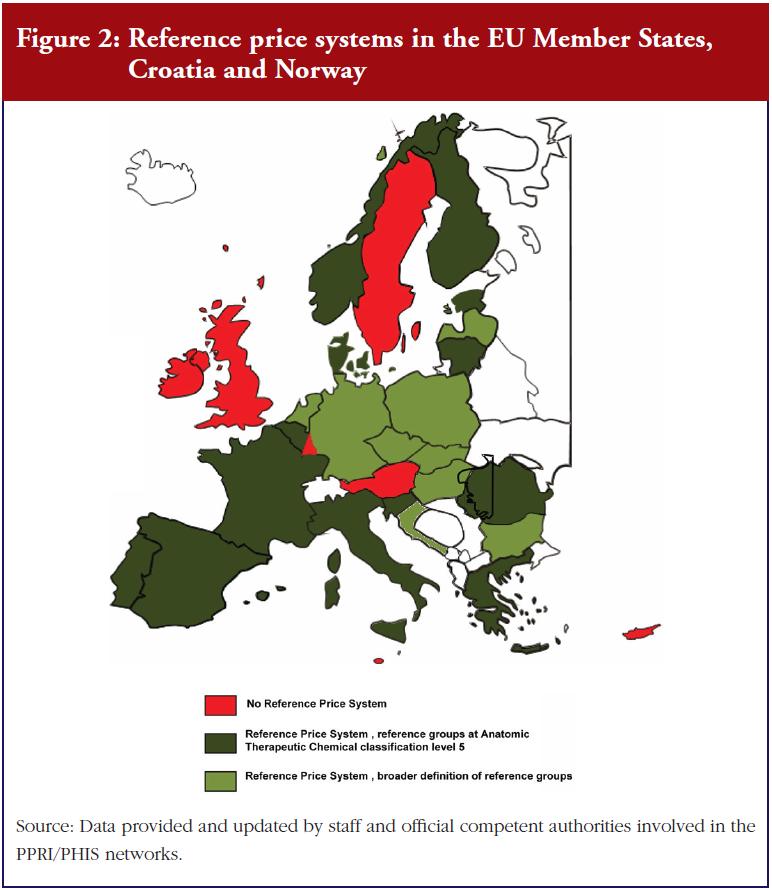

Several countries apply a pricing policy that sets the price of follower products in relation to the price of the originator medicine. For generics, this is called ‘generic price link’. It is a commonly used practice that is applied in 30 of the 42 surveyed countries. Fifteen countries reported that they also apply such a strategy for biosimilar medicines. These are Austria, the Baltic States, Croatia, the Czech Republic, France, Iceland, Italy, Kazakhstan, Norway, Portugal, Romania, Slovakia and South Africa. Four ‘generic price link’ countries (Belgium, Bulgaria, Finland and Turkey) informed us that they do not apply a price-link policy for biosimilars. A further 10 European countries and Canada apply a generic price link but did not report whether they also use this policy for pricing biosimilar medicines.

In most of the countries that apply a generic and biosimilar price link, the price difference between the originator medicine and the biosimilar is, sometimes considerably, lower than that between originator and generic medicine. This implies that biosimilar medicines tend to have higher prices. For instance, in the Czech Republic the first generic drug must be priced 32% below that of the originator, whereas the price of the first biosimilar must only be 15% lower than the originator. Six countries (Austria, Iceland, Italy, Kazakhstan, Latvia and South Africa) apply the same price link for generic and biosimilar medicines. However, the design of this link is heterogeneous. In Italy for example, a Decree was passed that treats generics and biosimilars in the same way in the procedure of reimbursement. Both can automatically be reimbursable and classify for the same reference group as their originator, if the price proposed by the respective marketing authorization holder is favourable to the Italian Health Service. Austria (at the time of the survey, for information on further developments see the Discussion paragraph) and Latvia, on the contrary, have defined a percentage threshold under which the first follower – either generic or biosimilar – must be priced (48% and 30%, respectively), and percentage rates of how much the prices of further ‘followers’ must be lower than of previous generics or biosimlars. In Iceland, the price link is calculated based on the maximum wholesale price allowed for generic and biosimilar medicines. Figures 1 and 2 describe price-link policies for biosimilars and generics, including price differences.

Some countries in the survey described the use of tendering to procure biosimilars. Iceland and the UK for instance have been tendering for medicines, including biosimilars, in the inpatient sector. In Denmark, all medicines (including biosimilars) for the inpatient sector are procured by a national procurement agency (AMGROS) which is owned by the five ‘health regions’ [25]. The Norwegian Drug Procurement Cooperation is responsible for purchasing medicines for public hospitals through annual tender processes. To ensure the acceptance of the awarded products, the results of the tender process and recommendations are presented by an expert group to affected stakeholders (industry, patient organizations, doctors) [26]. A similar approach is applied in Italy, however, in a decentralized manner; 20 Italian Regional Health Authorities (RHA) are responsible for planning healthcare services and allocating financial resources. All RHAs have established an organization for purchasing goods and services and two of them (Emilia-Romagna and Tuscany) additionally appointed a separate authority for procuring medicines. Various tenders for off-patent biologicals are conducted at regional levels [27]. In Spain, a pilot project of centralized procurement was reported to have taken place for the glycoprotein hormone and anaemia treatment erythropoietin (EPO).

Tendering in the outpatient sector is particularly used to procure for ‘public functions’, e.g. vaccines, centralized procurement in emergency situations such as pandemics [28]. Cyprus and Malta, both countries in which pharmaceutical services are provided separately by a public and a private sector, procure medicines (including biosimilars) for the public sector through tendering [29–31]. Some European countries have introduced tenders or tender-like systems in the outpatient sector; public payers launch tender calls for medicines that have generic (same active ingredient) or therapeutic alternatives. The lowest bidder will be either warded the contract to supply the whole market or will be granted a preferential position on the reimbursement list, e.g. through higher coverage. Such a policy is applied in The Netherlands, where through the ‘preferential pricing policy’ health insurers tender for the lowest-priced off-patent medicine [28, 32, 33]. However, biosimilar medicines were only recently included in the tenders, and only by a limited number of insurers [25]. A tender-like procedure is also applied in the Danish off-patent outpatient market, which also includes biosimilar medicines. In their system, pharmaceutical companies submit bi-monthly price bids and the lowest-priced medicines are selected for full reimbursement within a two-week period [25, 33–36].

Demand-side measures to encourage biosimilar uptake

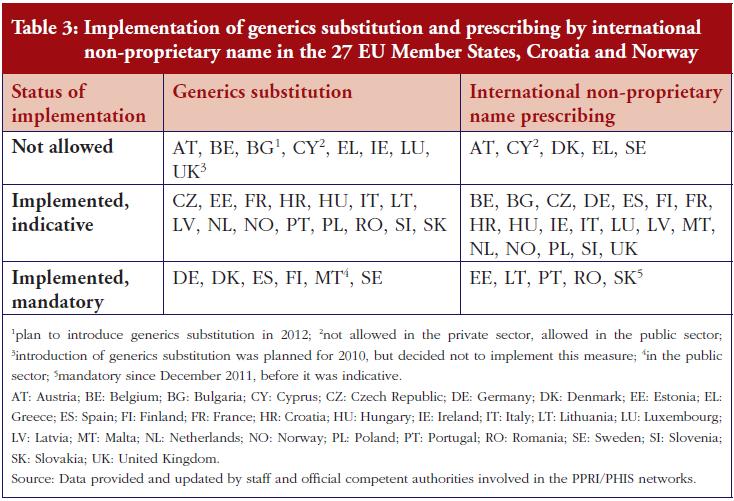

Prescribing by INN is a measure enforced by doctors that supports the uptake of generics as well as biosimilars. INN prescribing is in place in 35 European countries, Canada and South Africa, and is mandatory in 14 of the surveyed countries. It is only in Austria, Denmark, Serbia and Sweden that prescription by INN is not permitted, see Figure 3.

Another key demand-side measure to enhance the uptake of off-patent medicines is to allow community pharmacists to substitute the originator medicine with an off-patent medicine. Generics substitution is a commonly used practice. It is applied in 37 of the 42 countries (it is not permitted in Austria, Bulgaria, Denmark, Luxembourg and Serbia), and mandatory in 15 countries. In contrast, substitution of biosimilar medicines is only in place in some, mainly Central and Eastern European countries: Belarus, Cyprus, Czech Republic, Estonia, France, Iceland, Israel, Kazakhstan, Latvia, Malta, The Netherlands, Poland, Russia, Slovakia, Slovenia and Turkey. In some countries, e.g. Latvia, the substitution of an originator medicine by a biosimilar has not been explicitly implemented, but INN prescribing is obligatory and the medicine of the lowest price must be dispensed in the pharmacy, e.g. Latvia. There is usually no specific legal basis for biosimilar substitution; no law explicitly prohibited biosimilar substitution. In France, biosimilar substitution was introduced by the Social Insurance Law at the beginning of 2014 but is not yet in practice. Other countries reported opposition to biosimilar substitution by some stakeholders. In the Czech Republic for example, the Chamber of Pharmacists recommended against biosimilar substitution.

Pricing and reimbursement policies for biosimilar medicines, as for generics, are embedded in the overall pricing and reimbursement framework. Policies for biosimilar medicines might be expected to be similar to those for generics, yet our survey showed that this is the case for only some policies and varies by country.

With regard to pricing of generic and biosimilar medicines, there are, in principle, two different approaches: to allow free pricing for off-patent medicines, and to allow for competition. The incentive for pharmaceutical manufacturers to offer low prices is to achieve higher market shares, since the lowest-priced medicines are likely to obtain more public funding and/or be recommended to pharmacists, doctors and patients. Reimbursement strategies, such as a reference price system or tendering for off-patent medicines, likely support competition.

An alternative policy is price regulation, typically in the form of a price link, whereby the price of a generic or biosimilar medicine is determined in relation to the originator price. This pricing policy appears to be commonly applied for generic medicines, even in combination with external price referencing (international price comparison) in several countries including Belgium, Hungary, Poland and Spain. In some countries, a price-link policy is applied for biosimilars as well. All countries that apply the price-link policy for biosimilar medicines do the same for generics. The survey showed, however, that several countries with a price-link policy for generics do not have one for biosimilar medicines. While four generic price link countries explicitly advised that they do not apply a price link for biosimilars, other countries with a generic price-link policy did not respond to the question about the use of price linkage for biosimilars. This suggests that legislation on this issue has not yet been decided, likely due to the novelty of the topic.

In 2016, a few countries, e.g. Austria, South Africa, did not apply specific pricing regulation for biosimilar medicines. They used the same procedures for all off-patent medicines, whether or not these medicines were generics or biosimilars (in Austria, for instance, legislation valid at the time of the survey referred only to ‘follower products’). Furthermore, the required price difference between the originator and follower medicine did not distinguish between biosimilars and generics in these countries. In most countries, however, the price difference was lower for the originator-biosimilar pair compared to the originator-generic pair. This indicates that competent authorities in these countries grant comparatively higher prices to biosimilar medicines.

Few large-scale price comparisons include biosimilar medicines, and therefore information about the impact of the two approaches for pricing biosimilars (price link versus competition) is not available. For generics, an illustrative study of selected active ingredients [37] showed that countries that base their pricing policy for generic medicines on competition tend to have a larger price difference between the originator and the generic medicine, and generics prices are often (but not consistently) lower [7, 38–41].

Overall, tendering appears to be an effective instrument to generate savings for public payers. Norway for example, reported huge discounts for biosimilar infliximab (minus 72% in 2015) [26]. Research into biosimilar tenders by regions of Italy revealed that for 191 analyzed lots referring to three off-patent biologicals (somatropin, epoetin and filgrastim) mentioned in 24 tenders performed between 2008 and 2012, the price of filgrastim and epoetin dropped considerably, whereas the price of somatropin remained steady. Somatropin had the lowest mean number of competitors (1.16), while filgrastim had the highest (2.75) [16]. Both Norway and Italy applied tenders targeted at biological and biosimilar medicines in the hospital sector. This is in line with the results of the EBE study on pricing and reimbursement policies for biological medicines, which showed that, while biological medicines are subject to tenders in several European countries, these are hospital tenders in the majority of cases [18]. Despite evidence of its effectiveness, tendering has rarely been applied for biosimilar medicines in the outpatient sector. Dutch health insurers are experienced in tendering for off-patent medicines but have traditionally refrained from including biosimilars in their tenders [42, 43]. Only recently have some Dutch insurers started launching tenders for biosimilars [25]. According to Dutch respondents, this is to be seen in the light of physician reluctance towards biosimilar medicines; while switching from the originator to a biosimilar medicine is allowed and would be appreciated by the competent authorities, it is not yet common practice.

However, pricing is only one aspect of encouraging generics and biosimilars use. Policies are also required that ensure the use of lower-priced medicines instead of higher-priced originator medicines. It is of key importance that patients trust generics and biosimilars; otherwise, they will insist on receiving the originator medicines even if they must pay more. Health professionals such as doctors and pharmacists play a key role in this respect, as their contributions in some countries such as Germany and Norway have shown [15, 44]. Health professionals must themselves understand the value of generics and biosimilars in order to communicate it to the patients. Thus, education and possibly incentives for health professionals are needed [45].

Much debate has centred around interchangeability and switching from originator medicines to biosimilars. Recent studies have been launched to prove the safety of switches [46], such as the NOR-SWITCH study, whose preliminary results suggest that a switch from originator infliximab to biosimilar infliximab is safe [47].

The Australian government announced in early 2015 that biosimilar medicines can be substituted by pharmacists based on the clinical recommendations of the Pharmaceutical Benefits Advisory Committee. The same rules that apply to generics also hold for biosimilars, and pharmacists are permitted to substitute any biosimilar medicine for an originator product, in the absence of clinical evidence to the contrary [48]. In Europe, however, biosimilar substitution has not been widely implemented, despite advanced generic medicines substitution. Countries that allow biosimilar substitution (or, at least, do not explicitly prohibit it) have been confronted with opposition by pharmacists and doctors.

It is important to note the limitations to this survey study. It concerns a new area for which data are scarce, and knowledge is limited. Since in many cases the literature does not provide conclusive information, we used primary data from members of the PPRI network, who are experts in the field of pharmaceutical pricing and reimbursement. However, we experienced a lower response rate to some of the specific questions related to biosimilar medicines. This could be a reflection of the novelty of the area for which specific policies are yet to be defined. Due to the novelty of the topic, terminology was not fully clear to all respondents, e.g. the distinction between switching by doctors and substitution by pharmacists. We addressed these challenges by providing definitions, arranging a debate of preliminary findings during a face-to-face meeting and organizing a second round of the survey based on a slightly revised questionnaire. We also aimed to validate responses using the literature, although this was not possible in several cases due to a lack of information or contradictions between sources, e.g. information on biosimilar substitution. This makes it difficult for us to discuss our findings in the light of existing literature. Further, our findings are not comprehensive. For instance, we did not survey the ‘switch climate’ or regulations for switches in different countries, as we felt that existing research had already covered these areas. The findings refer to the situation at the time of the survey (Spring 2016); in the meantime, changes in legislation might have occurred (as with the price-link policy in Austria, for instance, when in April 2017 different percentage rates for the price difference of the originator-biosimilar pair and of the originator-generic pair were introduced). Finally, this research is descriptive, and does not assess the possible impacts of policies on biosimilar prices or uptake.

Despite these limitations, we believe that our study provides interesting and updated results. Apart from the EBE study published in the same journal [18], this is the sole recent study that considers biosimilar and generic medicines policies across a large number of countries, including several non-European nations. The study also provides value by surveying both generic and biosimilar medicines, allowing a comparison between these two groups of medicines. Such a comparison has not been provided by past studies, including the above-mentioned [18], which only focused on biological and biosimilar medicines. The broad focus of our study (generic and biosimilar medicines policies) offers novel information. Due to the novelty of the topic, it is difficult to compare our findings with those of other research.

This study provides information about pricing policies and demand-side measures to enhance the uptake of biosimilar medicines for over 40 countries and compares them to practices applied for generics. Some aspects surveyed here have not been previously discussed in the literature.

Overall, the study shows that European countries have made good use of available policies for pricing generics and enhancing their uptake. However, with regard to biosimilar medicines, policymakers in several countries appear to be struggling to identify the most appropriate approach. Indeed, in many countries, pricing and usage-enhancing policies for biosimilars have not yet been defined. Policymakers do not always apply instruments that have been successfully implemented for generics to biosimilar medicines. The reluctance to do so might result from opposition to biosimilar medicines expressed by some stakeholder groups, such as physicians.

There is a need for further research to investigate the possible impacts of biosimilar medicines policies on prices, uptake and expenditure. Given the ongoing development of policies for biosimilar medicines, such studies need to be designed with a long-term perspective. Descriptive surveys, such as this manuscript, on poli cies and practices will help to inform such impact assessments.

Biosimilar medicines have the potential to increase patient access to medicines. Their prices are lower than those of originator medicines, which help to make biological medicines more affordable. Biosimilar medicines contribute to reduced pharmaceutical expenditure and thus free financial resources, ultimately allowing a greater number of patients to be treated. Policymakers are called upon to introduce policies for the pricing, funding and promotion of biosimilar medicines in order to take advantage of these benefits. However, successful implementation of pharmaceutical policies related to biosimilar medicines, as described in this article, requires patients’ understanding and acceptance. This research aims to contribute to patient knowledge in this area.

Country abbreviations

AL: Albania; AT: Austria; BE, Belgium; BG: Bulgaria; BY: Belarus; CA: Canada; CH: Switzerland; CY: Cyprus; CZ: Czech Republic; DE: Germany; DK: Denmark; EE: Estonia; EL: Greece; ES: Spain; FI: Finland; FR: France; HR: Croatia; HU: Hungary; IE: Ireland; IL: Israel; IS: Iceland; IT: Italy; KG: Kyrgyzstan; KZ: Kazakhstan; LT: Lithuania; LU: Luxembourg; LV: Latvia; MT: Malta; NL: The Netherlands; NO: Norway; PL: Poland; PT: Portugal; RS: Republic of Serbia; RU: Russia; RO: Romania; SE: Sweden; SI: Slovenia; SK: Slovakia; TR: Turkey; UA: Ukraine; UK: United Kingdom; ZA: South Africa.

Contributors: The authors thank their colleagues Ms Nina Zimmermann and Ms Margit Gombocz in the Pharmaceutical Pricing and Reimbursement Information (PPRI) Secretariat for their support in the data collection of the survey. Furthermore, we gratefully acknowledge the answers to the survey provided by PPRI network members.

Funders: No funding was received for writing this manuscript. The Austrian Federal Ministry of Health and Women’s Affairs financially supports the Pharmaceutical Pricing and Reimbursement Information (PPRI) Secretariat.

Prior presentations: Preliminary results related to one aspect of the presented research (pricing policies for biosimilar medicines) were presented at the ISPOR 19th Annual European Congress in Vienna, Austria, 31 October – 2 November 2016.

Funding source: The authors gratefully acknowledge the support of the Austrian Federal Ministry of Health and Women’s Affairs to the Austrian Public Health Institute for running the PPRI (Pharma ceutical Pricing and Reimbursement Information) Secretariat that is managed by the authors and colleagues. The members of the PPRI network (competent authorities for pharmaceutical pricing and reimbursement) supported this research by providing data and information for this manuscript. No funding for writing this manuscript was received.

Competing interests: None.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Sabine Vogler, PhD; Peter Schneider, MA

WHO Collaborating Centre for Pharmaceutical Pricing and Reimbursement Policies, Pharmacoeconomics Department, Gesundheit Österreich GmbH (GÖG/Austrian Public Health Institute), 6 Stubenring, AT-1010 Vienna, Austria.

References

1. European Commission. Carone G, Schwierz C, Xavier A. Cost-containment policies in public pharmaceutical spending in the EU. Economics and Financial Afairs, 2012 [homepage on the Internet]. [cited 2017 May 26]. Available from: http://ec.europa.eu/economy_finance/publications/economic_paper/2012/pdf/ecp_461_en.pdf

2. World Health Organization. WHO Guideline on country pharmaceutical pricing policies. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2013 [homepage on the Internet]. [cited 2017 May 26]. Available from: http://www.who.int/medicines/publications/pharm_guide_country_price_policy/en/

3. Vogler S. The impact of pharmaceutical pricing and reimbursement policies on generics uptake: implementation of policy options on generics in 29 European countries–an overview. Generics and Biosimilars Initiative (GaBI Journal). 2012;1(2):93-100. doi:10.5639/gabij.2012.0102.020

4. Dylst P, Vulto A, Simoens S. Demand-side policies to encourage the use of generic medicines: an overview. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2013;13(1):59-72.

5. Simoens S, De Coster S. Sustaining generic medicines markets in Europe. J Generic Med. 2006;3(4):257-68.

6. Simoens S. Sustainable provision of generic medicines in Europe. Leuven, The Netherlands: KU Leuven 2013.

7. Simoens S. A review of generic medicine pricing in Europe. Generics and Biosimilars Initiative (GaBI Journal). 2012;1(1):8-12. doi:10.5639/gabij.2012.0101.004

8. Vogler S, Zimmermann N. How do regional sickness funds encourage more rational use of medicines, including the increase of generic uptake? A case study from Austria. Generics and Biosimilars Initiative Journal (GaBI Journal). 2013;2(2):65-75. doi:10.5639/gabij.2013.0202.027

9. Dylst P, Vulto A, Simoens S. The impact of reference-pricing systems in Europe: a literature review and case studies. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2011;11(6):729-37.

10. Godman B, Wettermark B, Bishop I, Burkhardt T, Fürst J, Garuoliene K. European payer initiatives to reduce prescribing costs through use of generics. Generics and Biosimilars Initiative Journal (GaBI Journal). 2012;1(1):22-7. doi:10.5639/gabij.2012.0101.007

11. World Health Organization. Cameron A, Laing R. Cost savings of switching private sector consumption from originator brand medicines to generic equivalents. World Health Report, Background Paper, 35. Geneva 2010 [homepage on the Internet]. [cited 2017 May 26]. Available from: http://www.who.int/healthsystems/topics/financing/healthreport/35MedicineCostSavings.pdf

12. World Health Organization. Regional Office for Europe. Access to new medicines in Europe: technical review of policy initiatives and opportunities for collaboration and research. Copenhagen, 2015 [homepage on the Internet]. [cited 2017 May 26]. Available from: http://www.euro.who.int/en/healthtopics/Health-systems/health-technologies-and-medicines/publications/2015/access-to-new-medicines-in-europe-technical-review-of-policy-initiativesand-opportunities-for-collaboration-and-research-2015

13. Derbyshire M. Patent expiry dates for best-selling biologicals. Generics and Biosimilars Initiative Journal (GaBI Journal). 2015;4(4):178-9. doi:10.5639/gabij.2015.0404.040

14. Haustein R, de Millas C, Höer A, Häussler B. Saving money in the European healthcare systems with biosimilars. Generics and Biosimilars Initiative Journal (GaBI Journal). 2012;1(3-4):120-6. doi:10.5639/gabij.2012.0103-4.036

15. Mack A. Norway, biosimilars in different funding systems. What works? Generics and Biosimilars Initiative Journal (GaBI Journal). 2015;4(2):90-2. doi:10.5639/gabij.2015.0402.018

16. Curto S, Ghislandi S, van de Vooren K, Duranti S, Garattini L. Regional tenders on biosimilars in Italy: an empirical analysis of awarded prices. Health Policy. 2014;116(2-3):182-7.

17. European Commission. What you need to know about biosimilar medicinal products. Consensus Information Document [homepage on the Internet]. [cited 2017 May 26]. Available from: http://www.medicinesforeurope.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/biosimilars_report_en.pdf

18. Acha V, Allin P, Bergunde S, Bisordi F, Roediger A. What pricing and reimbursement policies to use for off-patent biologicals? – Results from the EBE 2014 biological medicines policy survey. Generics and Biosimilars Initiative Journal (GaBI Journal). 2015;4(1):17-24. doi:10.5639/gabij.2015.0401.006

19. Mestre-Ferrandiz J, Towse A, Berdud M. Biosimilars: how can payers get longterm savings? Pharmacoeconomics. 2016;34(6):609-16.

20. Renwick MJ, Smolina K, Gladstone EJ, Weymann D, Morgan SG. Postmarket policy considerations for biosimilar oncology drugs. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17(1):e31-8.

21. Mendoza C, Ionescu D, Radière G, Rèmuzat C, Young K, Toumi M. Biosimilar substitution policies: an overview. Value Health. 2015;18(7):A525.

22. Drozd M, Szkultecka-D bek M, Baran-Lewandowska I. Biosimilar drugs–automatic substitution regulations review. Polish ISPOR chapter’s Therapeutic Programs and Pharmaceutical Care (TPPC) task force report. J Health Policy Outcomes Res. 2014;1:52-7.

23. Vogler S, Leopold C, Zimmermann N, Habl C, de Joncheere K. The Pharmaceutical Pricing and Reimbursement Information (PPRI) initiative–experiences from engaging with pharmaceutical policy makers. Health Policy Technol. 2014;3(2):139-48.

24. World Health Organization. List of participating Member States [home page on the Internet]. [cited 2017 May 26]. Available from: http://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/disease-prevention/vaccines-and-immunization/european-immunization-week/european-immunization-week-20052015/european-immunization-week-2012/list-of-participating-member-states)

25. Gombocz M, Vogler S, Zimmermann N. Ausschreibungen für Arzneimittel: Erfahrungen aus anderen Ländern und Umsetzungsstrategien für Österreich. 2016.

26. GaBI Online – Generics and Biosimilars Initiative. Huge discount on biosimilar infliximab in Norway [www.gabionline.net]. Mol, Belgium: Pro Pharma Communications International; [cited 2017 May 26]. Available from: www.gabionline.net/Biosimilars/General/Huge-discount-on-biosimilar-infliximab-in-Norway

27. Curto A, Van de Vooren K, Garattini L, Lo Muto R, Duranti S. Regional tenders on biosimilars in Italy: potentially competitive? Generics and Biosimilars Initiative (GaBI Journal). 2013;2(3):123-7. doi:10.5639/gabij.2013.0203.036

28. World Health Organization. Collaborating Centre for Pharmaceutical Pricing and Reimbursement Policies. Leopold C, Habl C, Vogler S. Tendering of pharmaceuticals in EU Member States and EEA countries. Results from the country survey. Vienna: ÖBIG Forschungs- und Planungsgesellschaft mbH, 2008 [homepage on the Internet]. [cited 2017 May 26]. Available from: http://whocc.goeg.at/Literaturliste/Dokumente/BooksReports/Final_Report_Tendering_June_08.pdf

29. Petrou P, Talias MA. Tendering for pharmaceuticals as a reimbursement tool in the Cyprus public Health Sector. Health Policy Technol. 2014;3(3):167-75.

30. Wouters OJ, Kanavos PG. Transitioning to a national health system in Cyprus: a stakeholder analysis of pharmaceutical policy reform. Bull World Health Organ. 2015;93(9):606-13.

31. Vogler S, Habl C, Leopold C, Rosian-Schikuta I, de Joncheere K. PPRI Report. Vienna: (PPRI), 2008. Available from: https://ppri.goeg.at/Downloads/Publications/PPRI_InterimTechnicalReport.pdf

32. Habl C, Vogler S, Leopold C, Schmickl B, Fröschl B. Referenzpreissysteme in Europa. Analyse und Umsetzungsvoraussetzungen für Österreich; Wien: ÖBIG Forschungs- und Planungsgesellschaft mbH; 2008.

33. Dylst P, Vulto A, Simoens S. Tendering for outpatient prescription pharmaceuticals: what can be learned from current practices in Europe? Health Policy. 2011;101(2):146-52.

34. Thomsen E, Er S, Schüder P. PHIS Pharma Profile Denmark. Vienna: Pharmaceutical Health Information System (PHIS), 2011.

35. Leopold C, Habl C, Vogler S, Rosian-Schikuta I. Steuerung des Arzneimittelverbrauchs am Beispiel Dänemark. Vienna: Gesundheit Österreich GmbH (Austrian Health Institute), 2008.

36. Ministry of Health Denmark/Danish Health and Medicines Authority. Flowchart of the pharmaceutical system in Denmark. Poster. 3rd International PPRI Conference on Pharmaceutical Pricing and Reimbursement Policies Challenges Beyond the Financial Crisis. 12–13 October 2015; Vienna, Austria.

37. Vogler S. How large are the differences between originator and generic prices? Analysis of five molecules in 16 European countries. Farmeconomia. Health Economics and Therapeutic Pathways. 2012;13(Suppl 3):29-41.

38. Simoens S. Developing competitive and sustainable Polish generic medicines market. Croat Med J. 2009;50(5):440-8.

39. Dylst P, Simoens S. Does the market share of generic medicines influence the price level?: a European analysis. Pharmacoeconomics. 2011;29(10):875-82.

40. Aalto-Setälä V. The impact of generic substitution on price competition in Finland. Eur J Health Econ. 2008;9(2):185-91.

41. Spinks J, Chen G, Donovan L. Does generic entry lower the prices paid for pharmaceuticals in Australia? A comparison before and after the introduction of the mandatory price-reduction policy. Aust Health Rev. 2013;37(5):675-81.

42. Progenerika. Kanavos P. Tender systems for outpatient pharmaceuticals in the European Union: evidence from The Netherlands and Germany. European Medicines Information Network (EMINet), 2012 [homepage on the Internet]. [cited 2017 May 26]. Available from: http://www.progenerika.de/wp-content/uploads/2013/02/Anlage-2_Tendering-Report-EMINET-13OCT2012-FINAL.pdf

43. European Commission. Kanavos P, Seeley L, Vandoros S. Tender systems for outpatient pharmaceuticals in the European Union: evidence from The Netherlands, Germany and Belgium. European Medicines Information Network (EMINet), 2009 [homepage on the Internet]. [cited 2017 May 26]. Available from: http://ec.europa.eu/docsroom/documents/7607?locale=en

44. Flume M. Regional management of biosimilars in Germany. Generics and Biosimilars Initiative Journal (GaBI Journal). 2016;5(3):125-7. doi:10.5639/gabij.2016.0503.031

45. Towse A, Mestre-Ferrandiz J, Berdud M, Brown JD, Walson PD, Godman B, et al. Biosimilars: achieving long-term savings and competitive markets. Generics and Biosimilars Initiative Journal (GaBI Journal). 2016;5(3):103-4. doi:10.5639/gabij.2016.0503.027

46. European Commission. Report of the multi-stakeholder workshop on biosimilar medicinal products. 2016 [homepage on the Internet]. [cited 2017 May 26]. Available from: http://ec.europa.eu/DocsRoom/documents/19302

47. Goll G, Olsen I, Jorgensen K, Lorentzen M, Bolstad N, Haavardsholm E, et al. Biosimilar infliximab (CT-P13) is not inferior to originator infliximab: results from a 52-week randomized switch trial in Norway. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016;68(Suppl 10).

48. IMS Health. Australia: substitution rules for biosimilars criticies by research based industry. IMS Pharma Pricing & Reimbursement. 2015;20(10): 306-2.

|

Author for correspondence: Sabine Vogler, PhD, Head of WHO Collaborating Centre for Pharmaceutical Pricing and Reimbursement Policies, Head of Pharmacoeconomics Department, Gesundheit Österreich GmbH (GÖG/Austrian Public Health Institute), 6 Stubenring, AT-1010 Vienna, Austria |

Disclosure of Conflict of Interest Statement is available upon request.

Copyright © 2017 Pro Pharma Communications International

Permission granted to reproduce for personal and non-commercial use only. All other reproduction, copy or reprinting of all or part of any ‘Content’ found on this website is strictly prohibited without the prior consent of the publisher. Contact the publisher to obtain permission before redistributing.

Source URL: https://gabi-journal.net/do-pricing-and-usage-enhancing-policies-differ-between-biosimilars-and-generics-findings-from-an-international-survey.html

|

Aim: To explore whether medicines used in hospitals in European countries are supplied as originators or generic medicines, and to investigate the procurement conditions, including the extent of discounts at which the medicines are provided. |

Submitted: 3 July 2014; Revised: 29 November 2014; Accepted: 4 December 2014; Published online first: 17 December 2014

In recent years, policymakers in European countries have increased strategies to improve the uptake of generic medicines. For instance, INN prescribing (i.e. prescribing medicines by active ingredient rather than brand name), generics substitution (i.e. the practice of substituting a brand name medicine with a generic equivalent), and/or a reference price system (i.e. identical or similar medicines are clustered to a reference group, and the public payer defines the maximum amount – reference price – which is used as the basis for reimbursement for all medicines in the group), have been implemented in most countries of the European Union (EU) [1–8]. These policies to enhance the prescribing of generics versus on-patent medicines have, to a lesser or greater degree, been supplemented by further measures, typically in the outpatient sector, such as prescription monitoring and budgets, information campaigns to the public and, somewhat less frequently, financial incentives for pharmacists and patients [9–14].

This is done to ensure the provision of high-quality medicines at a lower financial burden for the payer, which is either the patient or the third party payer (social health insurance institutions or National Health Service). In many European countries, the latter covers, at least partially, the cost of medicines [7]. Generics are procured at, in some cases, considerably lower prices than originator medicines and thus contribute to savings for the payers, as seen in several countries, e.g. Sweden and Scotland [12, 15–20].

Pharmaceutical policy measures have usually focused on the outpatient sector. Pharmaceutical expenditure in hospitals has been fairly constant over the years (usually 5−10% of a nation’s medicines budget), so it has not been a priority of policymakers in European countries [21]. Knowledge of pharmaceutical policies, including procurement and funding strategies, in the hospital sector in Europe has therefore been limited. While clinical issues have been covered by a large body of literature, policy-related research has been scant [22]. However, in recent years, this has been changing because of an increasing awareness of the need to learn about hospital-related pharmaceutical policies [23] and to improve the management of pharmacotherapy at the interface of the inpatient and outpatient sectors. Several countries have launched initiatives in this field [24].

This information gap is partly related to dual organization and funding of the pharmaceutical systems in the European countries. Medicines prescribed and supplied in outpatient care are funded by the third-party payer, usually the state, while the remainder has to be co-paid by the patient. The third party payer decides, based on pharmacological, therapeutic and health economic considerations, which medicines used in outpatient care are reimbursed [7]. In the inpatient sector, except for special funding models for high-cost medicines, medicines are financed out of hospital budgets, which are funded by the hospital owners, which might be the state, regions, municipalities, religious orders, or some pooled funding from taxes and social health insurance contributions, depending on the country’s organization of healthcare services [25].

The outpatient and inpatient pharmaceutical systems tend to be seen as two distinct sectors within a country, hence the increasing focus on improving the interface management of pharmacotherapy. However, it is increasingly recognized that medication started during the hospital stay can impact the future medicines prescribed after a patient has been discharged [26–33]. It has been suggested that it might be better to supply, at favourable conditions, hospitals with off-patent medicines in order to ensure the initial prescribing with these medicines. However, as far as the authors know, no study has ever looked at the availability of originators and generic medicines at the level of individual hospitals in European countries. This is increasingly essential as more standard treatments lose their patents [34, 35].

Against this backdrop, this study sets out to explore whether medicines used in hospitals in European countries are supplied as on-patent or generic medicines. Furthermore, we aim to investigate the procurement conditions, including the extent of discounts at which the medicines are provided.

The analysis for this manuscript draws from data collected during the European Commission co-funded PHIS (Pharmaceutical Health Information System) project, which aimed to survey medicine management in hospitals in European countries and to collect prices of medicines used in hospitals (particularly on-patent medicines) [36, 37]. The methodology of this study was influenced by overall methodological decisions taken earlier in that project. For instance, the data collection was done for a larger basket of medicines, predominantly on-patent oncology medicines without generic alternatives.

Selection of medicines

Out of a basket of medicines whose data we had surveyed, we selected those four molecules for which a ‘generic’ version was on the market. These were:

Table 1 provides the list of these four active ingredients indicating the ATC (Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical) code and the key therapeutic indication.

We included cardiovascular medicines because they account for high volumes in the outpatient sector, and the initial treatment in hospitals typically impacts further outpatient use [38].

At the time of the survey, the patent for clopidogrel had expired in some European countries, and not in others. In order to expand the study by another medicine not for cardiovascular treatment, we also included this blood product.

Selection of countries

We defined the following selection criteria for the countries, to ensure: 1) a geographic balance; 2) a balance between ‘old’ and ‘new’ EU Member States (acceded to the EU before and after May 2004) as well as European Economic Area (EEA)/European Free Trade Association (EFTA) countries; 3) a balance between countries with a social health insurance system and those with a general taxation-based system (national health service); 4) a balance between countries with a decentralized and a centralized procurement policy for medicines used in hospitals; and 5) a balance of countries of different economic situations. This is in line with cross-country comparisons available in the current literature [39].

Countries selected were Austria, The Netherlands, Norway, Portugal and Slovakia. We could not reach a balance in all cases, but we had countries from different geographic parts of Europe (criterion 1), at least one new EU Member State (Slovakia) and an EEA/EFTA country (Norway) (criterion 2), countries in different economic situations (criterion 5), and we had a balance regarding countries with a social health insurance system (Austria, The Netherlands, Slovakia) and those with a national health service (Portugal, Norway) (criterion 3). Centralized tendering for medicines in hospitals as a key procurement policy was organized in one country (Norway), and in two further countries it was done as a first step (Portugal) or for specific medicines (high-cost medicines; Slovakia) (criterion 4).

The selected countries had a variety of policies to enhance the prescribing and use of on-patent medicines versus generics. Table 2 provides an overview of country characteristics including their generic drug policies.

During the selection of the countries, country representatives (typically from pharmaceutical pricing and reimbursement authorities and national hospital pharmacy associations) involved in the PHIS (Pharmaceutical Health Information System) project as collaboration partners were addressed, and their support for the survey was sought. Thus, the willingness of the country representatives in our network was effectively an additional practical criterion for selection, and partially explains the selection of the countries, e.g. we did not manage to include a large country.

Survey instrument

A questionnaire was developed by the management team of the PHIS project, i.e. the authors and colleagues at their institutions. The draft methodology papers, including the questionnaire, were circulated with the PHIS Advisory Board (European Commission, Executive Agency for Health and Consumers, Eurostat, OECD, WHO Europe and WHO Headquarters) and the PHIS network members and then revised following their feedback. The methodology was piloted in two hospitals in Portugal and in one hospital in Austria, and adjustments to the questionnaire were based on the lessons learned from the pilot.

The questionnaire consisted of two parts: 1) a price survey form; and 2) a general questionnaire. The price survey form listed the selected molecules and asked for information about their availability, prices and procurement conditions in the hospitals. Information about the general availability in the country (marketing authorization) and price data for the outpatient sector (ex-factory prices for Austria, Portugal, Slovakia and pharmacy purchasing prices for The Netherlands and Norway) as of 30 September 2009 were already pre-filled with data provided by the Pharma Price Information (PPI) service of Gesundheit Österreich GmbH (Austrian Health Institute) [68]. Hospital pharmacists in the participating hospitals were asked to provide data as of 30 September 2009 on the availability, actual (real) prices at which medicines were supplied and procurement conditions, e.g. tendering processes versus direct negotiations, discounts, cost-free medicines, from the internal hospital databases. The general questionnaire contained questions about the medicines management in the surveyed hospitals.

Selection of the hospitals and data collection

The national network representatives were the ones identifying and approaching hospitals to explore their willingness to participate in the survey.

In Austria, The Netherlands, Norway and Portugal, we surveyed the data during study visits to the hospitals. Teams of at least two people, usually a researcher and a country’s representative involved in the PHIS network (from a competent authority for pharmaceutical pricing and reimbursement and/or a hospital pharmacy association), met with the hospital pharmacists and collected on site the information about the availability and procurement conditions (part 1 and 2 of the survey instrument). Only hospitals that had agreed in advance to participate in the survey were visited. Since none of the hospital pharmacists withdrew their cooperation during the study visit, the response rate was 100% in these countries.

In Slovakia, we had a mixed approach. We made study visits to three hospitals. In addition, we presented the project to hospital pharmacists during the general assembly of their national association and asked for their support by responding in writing to the price survey form and the questionnaire. Eight hospitals in Slovakia returned the filled price survey form and the questionnaire. This explains the considerably higher participation rate of hospitals in Slovakia compared with other countries.

We performed the study visits in the five countries and received the written questionnaires from Slovak hospitals between September 2009 and March 2010. On average, the study visits took about three hours per hospital1.

The survey results include data from five hospitals in Austria, three hospitals in The Netherlands, four hospitals in Portugal, two hospitals in Norway and eleven hospitals in Slovakia. We focused on general hospitals and on hospitals in public ownership. Most of the hospitals willing to participate were large hospitals, i.e. more than 500 acute care beds; or medium-sized hospitals, i.e. between 400 and 500 acute care beds. Table 3 provides an overview of the hospitals in the survey in relation to the total in the selected countries.

Data analysis

Data for all presentations (a presentation is defined as a medicine in a specific pharmaceutical form, dosage and pack size) of the four selected molecules supplied to the hospitals were collected. For the purpose of the analysis, we defined a ‘common presentation’, for which we performed the comparison of availability and procurement conditions. Findings about further presentations are also presented, see Table 4.

Terminology

This paper uses the terminology as defined in the glossary on pharmaceutical terms developed by the WHO Collaborating Centre for Pharmaceutical Pricing and Reimbursement Policies [69]. Availability is defined as follows: The product is (physically) reachable for the patient, e.g. through the most accessible/appropriate healthcare supplier(s) at all times in adequate amounts and in the appropriate dosage forms, with assured quality and adequate information – so that patients have access to the medicine’. A discount is defined as ‘a price reduction granted to specified purchasers under specific conditions prior to purchase’, whereas a rebate is ‘a payment made to the purchaser after the transaction has occurred’. Country-specific terms for discounts and rebates, e.g. ‘rappel’ in Portugal, and procurement, e.g. ‘market surveillance’ in Slovakia, will be explained in the results section (see Table 4).

Figure 1 provides an overview of the availability of the selected medicines as originator or generic versions in the hospitals of the survey. Table 4 presents further information related to the procurement conditions, including the extent and types of discounts provided. Different procurement conditions surveyed were: cost-free provision, central tendering, market surveillance and individual purchase by the single hospital.

Variations were found between the countries and molecules: Hospitals in Norway, Slovakia and also Portugal and The Netherlands had the generics version more frequently available than did hospitals in Austria. Generic clopidogrel was only available in Slovakia, where the patent had already expired. Except for Norway, originator atorvastatin tended to be supplied to hospitals more frequently than the generic version, whereas simvastatin had the highest generic availability among the surveyed cardiovascular medicines across all countries. Except for Austria, amlodipine was preferably supplied as generic versions.

With the exception of one medicine in one hospital in Portugal, all surveyed hospitals had at least one presentation of the selected medicines. Hospitals in Austria, The Netherlands and Portugal always had exactly one presentation of the active ingredients, either originator or generic versions. In a few cases hospitals in Norway and Slovakia had both originator and the generic versions of the same presentation of a cardiovascular medicine. There was one hospital in Slovakia, which already had the generic version of clopidogrel, in addition to the originator.

Norway is the only country in which the surveyed medicines were exclusively centrally tendered, and the tendered presentations, independently whether they were originators or generics, were granted comparably high discounts. In Portugal, medicines used in hospitals were centrally tendered in a first step, during which an official tendering price to be valid for some years was set, and in a second step hospitals individually purchased the medicines they needed and could sometimes negotiate lower prices. In the other countries, hospitals individually procured the medicines from their suppliers, typically manufacturers and in very few cases wholesalers. For specific medicines, some hospitals in Slovakia used an instrument called ‘market surveillance’; i.e. a limited tendering process in which bids from three suppliers were requested and evaluated.

Discounts of 100% were observed in Austria (in the case of all three cardiovascular medicines in all hospitals) and in Slovakia (in very few cases) regardless of whether the originator or a generic version was supplied. A discount of 100% means that the medicines were provided to the hospital ‘cost-free’. Discounts in Portugal were difficult to assess at product level since they were granted in the form of a so-called ‘rappel’ during the purchase process of the hospital. Rappels are ex-post rebates, usually implemented at the end of the calendar year, with a bundling element, since they were granted to hospitals for a specific sales volume of all medicines of a supplier during a year.

The study looked at the availability of a small sample of medicines in hospitals in medium-sized European countries, to learn whether these medicines were available and in which form. We found that, with one exception, all surveyed medicines were available in all 25 surveyed hospitals. One hospital in Portugal did not have simvastatin; we were informed that the hospital had decided against procuring it since other medicines (atorvastatin) were considered sufficient as therapeutic choice.

The findings of our study, though exploratory due to the limited number of medicines and hospitals surveyed, highlight differences in availability between the outpatient and the hospital sectors. The selected medicines were marketed and were provided in community pharmacy in several different formats (different dosages and pack sizes) in the five countries (information provided by the PPI service [68]), but the hospitals usually had very few formats of a medicine, in most cases often exactly one format. This confirms that dispensing practices in hospitals are different than those in community pharmacies. In hospitals, single-dose packing is applied, whereas in the outpatient sector the full pack is dispensed to the patient who should then take the medication according to the instructions. In hospitals, therefore, medicines of a pack (large packs are purchased) are generally used for several patients.

Given the focused availability in hospitals, pharmaceutical companies are incentivized to be the sole supplier of a molecule to the hospitals. Even if the sales volume per product might be limited in the single hospitals, supplies for inpatients can be considered as strategically important for those medicines which will be used for long-term treatment in outpatient care after the patient’s discharge from hospital. Particularly if there are no or limited policies to enhance generics use in the outpatient sector (such as mandatory generics substitution, INN prescribing, information campaigns to the public, see Table 2 for an overview of these policies in the five countries), a change to the generic drug might be unlikely once treatment was started with an on-patent product. Reluctance by general practitioners to switch from the originator to a generic drug was even reported in Germany [70], a country with active generic drug promotion policy resulting in overall high generics uptake [71, 72]. Cardiovascular medicines, whose availability in hospitals we surveyed, are a typical example [27, 28, 38].

The stakeholders involved have conflicting objectives. Suppliers have a commercial interest to gain market shares, ideally to ensure sales volumes in the long run, whereas payers aim to keep costs down. Since several European countries have different public payers and/or different funding sources for the pharmaceutical bill in the outpatient and inpatient sectors [21, 22, 25, 63], the outpatient and inpatient payers are incentivized to shift treatments, patients, and costs from one sector to another. This is likely to impact the health outcomes of patients negatively, since such situations can irritate patients, and lead to medication errors [73–77].

Given these organizational and financial frameworks, the findings of our study are not surprising. Hospital pharmacists are under financial pressure to procure best prices within the existing pharmaceutical budgets, and they will thus purchase from those suppliers who offer the highest discounts. The purchasers’ approach is illustrated by the data that we collected on Austria. Austria is one of a few European countries in which cost-free provision of medicines to hospitals is allowed [22, 25, 40]. This procurement strategy is commonly used, at least for some medicines. In general, hospitals in Austria were not able to obtain discounts for new on-patent medicines, or to receive them as cost-free medicines [22, 25, 63, 78], but the five hospitals of the survey received the three cardiovascular medicines cost-free, two of which were originator brand-name medicines. We do not know whether generics manufacturers were in the position to offer as high discounts as the originator industry. Suppliers of originator medicines may benefit from longer-lasting business relationships with the hospitals and can adapt the marketing strategy in advance of patent expiry. Furthermore, suppliers that offer a range of medicines for different indications may be able to offer specific delivery conditions, including some kind of bundling. The cost-free provision of originator cardiovascular medicines in hospitals may considerably impact the continued use of originator medicines in outpatient care, particularly since Austria does not have INN prescribing, generics substitution or a reference price system [1]. Given the limited demand-side measures to enhance generics uptake, see Table 2, sickness funds (social health insurance institutions) as public payers for outpatient medication are required to constantly undertake information activities and prescribing monitoring. Due to dual financing, the key target groups are prescribers in the outpatient sector, and only recently sickness fund launched information activities addressing prescribers and staff in hospitals, however as a voluntary initiative, since social health insurance is not responsible for funding medicines in hospitals [10].

Stakeholders react in response to the incentives provided by the system. Interviews in Austria confirmed that hospital pharmacists were aware of the dilemma of supporting the start of a treatment with an originator medicine, but since they are responsible to their hospital administration, they will act in the best interest of the hospital.

The purchasing power of a single hospital might be questioned. Even if some hospitals might be able to obtain higher discounts, e.g. hospitals in Slovakia, overall the findings displayed rather small differences in discounts between the hospitals, and they suggested limited headroom of the individual hospitals to negotiate large price reductions. Central tendering is likely to be connected with stronger purchasing power. Norway has decided that medicines for all public hospitals are centrally procured by the public procurement agency LIS (Legemiddelinnkjøpssamarbeid, Drug Procurement Cooperation). LIS defines preferred presentations and tenders for them. Medicines not tendered by LIS, e.g. different pack sizes, dosages, can be purchased individually by the hospitals [49]. The data from our survey showed that LIS tended to define a generic as a preferred version of the surveyed cardiovascular medicines. It was reported that hospitals in Norway had individually purchased some other ‘non-preferred’ presentations of these molecules, and they were not granted any discounts. The example of Norway could be considered as good practice since it combines financial elements with awareness-raising activities targeting prescribers. LIS staff have performed extensive information activities in hospitals to inform doctors about the defined presentations, and the rationale behind for selecting them. At the same time, the practice highlights the relevance of financial incentives that, in the case of Norway, support measures to enhance generics use in hospitals. In a country such as Austria, on the other hand, generics promotion activities of hospital pharmacists (via the Drugs and Therapeutics Committee, for instance, and their generics substitution which has been performed in hospitals for years but is not permitted in the outpatient sector) [40] are less effective since a limited number of generics are available due to cost-free provision of the originators to hospitals.

We also included clopidogrel in the basket of surveyed medicines even if the patent had only expired in Slovakia at the time of the survey. We learned in the interviews that hospital pharmacists in the other countries were eagerly awaiting the patent expiry because they aimed to change to the generics version as soon as possible, and obtain larger discounts and even cost-free provision in the case of Austria. However, hospital pharmacists might not see their expectations fulfilled given the controversy regarding generic clopidogrel, which was launched as a different salt with fewer indications initially [79, 80].

Our study has several limitations. A major limitation concerns the small basket of medicines, with only three cardiovascular medicines plus clopidogrel, which is still patented in most of the countries studied. In addition, the number of hospitals varied among the countries and was low in some countries. We were not always able to obtain complete information on the procurement conditions, particularly on the discounts, since in Portugal the ‘rappel’, an ex-post bundling rebate, allowed at best estimates on the product-specific price reductions. Some limitations were related to the medicine procurement system in a country, such as the Portuguese ‘rappel’. Also, this study was a follow-up of a larger study within the PHIS project, in which we surveyed more medicines, particularly on-patent medicines without any generic alternatives. The overall setting of the EU funded PHIS project has, to a large extent, contributed to some methodological decisions. Competent authorities and hospital pharmacists, who were already members of the PHIS network, were involved as cooperation partners in the survey, and not academics. Finally, we acknowledge that the study focused on the aspect of procurement of medicines to hospitals and, though we discussed the implications of the supply of originators and generics versions for the overall healthcare system, in the light of existing generic drug policies in the outpatient sector, the issue of improving use of generics was not within the scope of this study.

Therefore, this study can only be considered as an exploratory piece of research. We recommend repeating the survey, applying the same survey design, but with a larger basket of medicines (including medicines with generics available due to recently expired patents) and including more hospitals and countries.

Notwithstanding its limitations, the study provides important new evidence. Medicines procurement policies and management in European hospitals have been overlooked by researchers and policymakers for a long time, and the investigation of pharmaceutical policies in the inpatient sector has been called for [23]. To our knowledge, the availability of originator and generic medicines in European hospitals has never been surveyed. In the EU and other high-income countries, including the US and Australia, studies on the availability of medicines have been limited to the outpatient sector, and availability not measured at the level of the single healthcare provider (pharmacy, retailer) but at the national level [81, 82]. Primary data collected on availability and prices of medicines in single healthcare units and dispensaries (e.g. hospitals, clinics, pharmacies, and retailers) have been performed based on the WHO/HAI methodology [83] in some low- and middle-income countries [84, 85] but not in high-income countries. We were able to survey additional data about the procurement conditions; particularly discounts and rebates considered as confidential information.

The study confirms the general availability of the selected medicines, and, at the same time, highlights the strategy of hospitals to be focused on one or a few presentations of a molecule. If generic alternatives are available, generics tend to be supplied to the hospitals but this is not always the case. Cardiovascular medicines, which were studied in this survey, are of relevance for both industry and public payers, since they account for high volumes due to high patient numbers and long-term use. The initial treatment in hospitals is likely to impact further medicine use in the outpatient sector and to result in a continuation of the same brand, especially if pharmaceutical policies do not encourage a switch to a generic version. The study provides a good starting point to learn about originator and generic medicines use in hospitals. The findings suggest the need to develop policies that support a more integrative healthcare system, e.g. via joint funding models for the outpatient and inpatient sectors, in order to improve medicine management at the interface of outpatient and inpatient sectors.

For patients it is important to obtain the medical treatment they require. Availability of and access to medicines is one major element. The selected medicines were found to be available in the surveyed hospitals.

Generics provide an opportunity for a more rational use of medicines and for savings to public payers. Starting treatment with generics in the hospitals would be appreciated: public payers would achieve savings, and patients would continue in outpatient care with the medication they started. The study showed that in case of the generics alternatives available these are used in some but not all hospitals. In addition, the study suggests the need for improved pharmaceutical policies at the interface of the outpatient and inpatient sectors. Limited interface management directly impacts patients in a negative way, and can contribute to confusion, irritation and even deteriorated health outcomes of the patient.

We thank the hospital pharmacists of the 25 hospitals for their willingness to participate in this study. We are very grateful that they took the time to answer our questions during the interviews and that they shared with us the data which were of confidential character in most cases. Since we assured anonymity to the hospitals concerned, we do not disclose the names of data providers. We are grateful to our (former) colleagues Claudia Habl, Christine Leopold and Simone Gritsch (Gesundheit Österreich GmbH), and Barbara Bilancikova (SUKL) for their involvement in the methodology development and survey at the time of the PHIS (Pharmaceutical Health Information System) project. We thank the PHIS Advisory Board (Jérôme Boehm, Artur Furtado, Aders Lamark Tysse, Giulia del Brenna, Christophe Roeland, Stefaan van der Spiegel of the European Commission; Anna Thuvander, Jurgita Kaminskaite of the (then) Executive Agency for Health and Consumers, Dorota Kawiorska of Eurostat, Elizabeth Docteur, Valérie Paris of OECD, Kees de Joncheere of WHO Regional Office for Europe, Richard Laing and Dele Abegunde of WHO Headquarters – institutional affiliations refer to the time of the PHIS project) as well as the PHIS network members for their feedback to draft methodology papers. In particular, we greatly appreciate the support of the PHIS network members of selected countries in identifying and addressing hospitals for cooperation.

Competing interests: The authors have no reported conflicts of interest. The methodology development and the survey was done within the framework of the PHIS (Pharmaceutical Health Information System) project that was commissioned by the Executive Agency for Health and Consumers (EAHC) under the call for proposals 2007 in the priority area ‘health information’ of the European Commission, Directorate-General Public Health and Consumers, and was co-funded by the Austrian Federal Ministry of Health.

As a follow-up of the PHIS project, we analysed the data of medicines with a generic version available with regard to their availability and procurement conditions, and we prepared this manuscript. No separate funding was provided for the supplementary analysis regarding the research question and the drafting of this manuscript.

Provenance and peer review: Commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Sabine Vogler1, PhD

Nina Zimmermann1, MA

Jan Mazag2, PharmaDr

1WHO Collaborating Centre for Pharmaceutical Pricing and Reimbursement Policies, Health Economics Department, Gesundheit Österreich GmbH/Österreichisches Bundesinstitut für Gesundheitswesen (GÖG/ÖBIG, Austrian Health Institute), 6 Stubenring, AT-1010 Vienna, Austria

2Statny Ustav pre Kontrolu Lieciv (SUKL, State Institute for Drug Control), 11 Kvetná, SL-82508, Bratislava 26, Slovakia

References

1. Vogler S. The impact of pharmaceutical pricing and reimbursement policies on generics uptake: implementation of policy options on generics in 29 European countries–an overview. Generics and Biosimilars Initiative (GaBI Journal). 2012;1(2):93-100. doi: 10.5639/gabij.2012.0102.020

2. Vogler S, Zimmermann N, Leopold C, de Joncheere K. Pharmaceutical policies in European countries in response to the global financial crisis. South Med Review. 2011;4(2):69-79.

3. Leopold C, Vogler S, Habl C. Was macht ein erfolgreiches Referenzpreissystem aus? Erfahrungen aus internationaler Sicht [in German]/Implementing a successful reference price system – experiences from other countries. Soziale Sicherheit. 2008(11):614-23.

4. Dylst P, Vulto A, Godman B, Simoens S. Generic medicines: solutions for a sustainable drug market? Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2013;11(5): 437-43.

5. Simoens S. A review of generic medicine pricing in Europe. Generics and Biosimilars Initiative Journal (GaBI Journal). 2012;1(1):8-12. doi:10.5639/gabij.2012.0101.004

6. Dylst P, Simoens S, Vulto A. Reference pricing systems in Europe: characteristics and consequences. Generics and Biosimilars Initiative Journal (GaBI Journal). 2012;1:127-31. doi:10.5639/gabij.2012.0103-4.028

7. Vogler S, Habl C, Bogut M, Voncina L. Comparing pharmaceutical pricing and reimbursement policies in Croatia to the European Union Member States. Croat Med J. 2011;52(2):183-97.

8. Simoens S. Trends in generic prescribing and dispensing in Europe. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2008 Jul;1(4):497-503.

9. Dylst P, Vulto A, Simoens S. Demand-side policies to encourage the use of generic medicines: an overview. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2013;13(1):59-72.

10. Vogler S, Zimmermann N. How do regional sickness funds encourage more rational use of medicines, including the increase of generic uptake? A case study from Austria. Generics and Biosimilars Initiative Journal (GaBI Journal). 2013;2(2):65-75. doi:10.5639/gabij.2013.0202.027

11. Godman B, Shrank W, Wattermark B, Andersen M, Bishop I, Gustafsson LL. Use of generics – a critical cost containment measure for all healthcare professionals in Europe? Pharmaceuticals. 2010;3(8):2470-94.

12. Godman B, Shrank W, Andersen M, Berg C, Bishop I, Burkhardt T, et al. Comparing policies to enhance prescribing effi ciency in Europe through increasing generic utilization: changes seen and global implications. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2010;10(6):707-22.

13. Godman B, Shrank W, Andersen M, Berg C, Bishop I, Burkhardt T, et al. Policies to enhance prescribing effi ciency in Europe: fi ndings and future implications. Front Pharmacol. 2010;1:141.

14. Godman B, Wettermark B, Bishop I, Burkhardt T, Fürst J, Garuoliene K, et al. European payer initiatives to reduce prescribing costs through use of generics. Generics and Biosimilars Initiative Journal (GaBI Journal). 2012;1(1):22-7. doi:10.5639/gabij.2012.0101.007

15. World Health Organization. Cameron A, Laing R. Cost savings of switching private sector consumption from originator brand medicines to generic equivalents. World Health Report. Background Paper, 35. Geneva 2010 [homepage on the Internet]. 2011 Sep 17 [cited 2014 Nov 15]. Available from: http://www.who.int/healthsystems/topics/financing/healthreport/35MedicineCostSavings.pdf

16. Seeley E, Kanavos P. Generic medicines from a societal perspective: savings for health care systems? Eurohealth. 2008;14(2):18-21.

17. Simoens S. International comparison of generic medicine prices. Curr Med Res Opin. 2007;23(11):2647-54.

18. Tafuri G, Creese A, Reggi V. National and international differences in the prices of branded and unbranded medicines. Journal of Generic Medicines. 2004;1(2):120-7.

19. Vogler S. How large are the differences between originator and generic prices? Analysis of five molecules in 16 European countries. Farmeconomia Health economics and therapeutic pathways. 2012;13 (Suppl 3):29-41.

20. Bennie M, Godman B, Bishop I, Campbell S. Multiple initiatives continue to enhance the prescribing efficiency for the proton pump inhibitors and statins in Scotland. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2012;12(1):125-30.

21. Vogler S, Zimmermann N, Mazag J. Procuring medicines in hospitals: results of the European PHIS survey. Eur J Hosp Pharm Prac. 2011(2):20-1.

22. Vogler S, Zimmermann N, Habl C, Mazag J. The role of discounts and loss leaders in medicine procurement in Austrian hospitals – a primary survey of official and actual medicine prices. Cost Eff Resour Alloc. 2013;11(1):15.

23. Vogler S, Habl C, Leopold C, Rosian-Schikuta I. PPRI Report. Vienna: Gesundheit Österreich GmbH/Geschäftsbereich ÖBIG, 2008. 2008 Jun 2 [cited 2014 Nov 15]. Available from: http://whocc.goeg.at/Literaturliste/Dokumente/BooksReports/PPRI_Report_final.pdf

24. Björkhem-Bergman L, Andersén-Karlsson E, Laing R, Diogene E, Melien O, Jirlow M, et al. Interface management of pharmacotherapy. Joint hospital and primary care drug recommendations. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2013;69(1):73-8.

25. Vogler S, Habl C, Leopold C, Mazag J, Morak S, Zimmermann N. PHIS Hospital Pharma Report. Vienna: Pharmaceutical Health Information System (PHIS); commissioned by the European Commission and the Austran Federal Ministry of Health, 2010. 2010 Jul 16 [cited 2014 Nov 15]. Available from: http://whocc.goeg.at/Literaturliste/Dokumente/BooksReports/PHIS_HospitalPharma_Report.pdf

26. Perren A, Donghi D, Marone C, Cerutti B. Economic burden of unjustified medications at hospital discharge. Swiss Med Wkly. 2009;139(29-30):430-5.

27. Gallini A, Legal R, Taboulet F. The influence of drug use in university hospitals on the pharmaceutical consumption in their surrounding communities. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2013;75(4):1142-8.

28. Feely J, Chan R, McManus J, O’Shea B. The infl uence of hospital-based prescribers on prescribing in general practice. Pharmacoeconomics. 1999;16(2):175-81.

29. Schröder-Bernhardi D, Dietlein G. Lipid-lowering therapy: do hospitals influence the prescribing behavior of general practitioners? Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2002;40(7):317-21.

30. Himmel W, Tabache M, Kochen M. What happens to long-term medication when general practice patients are referred to hospital? Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1996;50(4):253-7.

31. Himmel W, Kochen M, Sorns U, Hummers-Pradier E. Drug changes at the interface between primary and secondary care. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2004;42(2):103-9.

32. Grimmsmann T, Schwabe U, Himmel W. The infl uence of hospitalisation on drug prescription in primary care–a large-scale follow-up study. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2007;63(8):783-90.