A review of international initiatives on pharmaceutical regulatory reliance and recognition

Published on 18 November 2024

Generics and Biosimilars Initiative Journal (GaBI Journal). 2024;13(3):151-9.

Abstract: |

Introduction

National Regulatory Authorities (NRAs) work under tremendous pressure to facilitate timely access to safe, effective, and good-quality health products worldwide. The global COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated this pressure, making the task of ensuring timely access to health products more challenging due to the increasing complexities of products, processes, and technologies, including outsourcing activities such as contract manufacturing, batch release testing, qualification and validation, clinical trials, and more.

This paper explores two strategies used by NRAs to ease this burden, namely:

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), Good reliance practices in the regulation of medical products: high level principles and considerations (TRS 1033 – Annex 10) [1]:

Regulatory reliance is an act whereby a regulatory authority in one jurisdiction may take into account or give significant weight to work performed by another regulator or other trusted institution when reaching its own decision.

Regulatory recognition is the routine acceptance of the regulatory decisions of another regulator or other trusted institution. Recognition indicates that evidence of conformity with the regulatory requirements of country A is sufficient to meet the regulatory requirements of country B.

If an NRA wishes to rely on the outcome of a certain decision or approval of health products or marketing authorization made by other NRA, trust is the only prerequisite for reliance. Building trust and establishing confidence are the starting points for reliance and recognition.

Current Initiatives

The development and evolution of ICDRA: a journey from 1980 to 2018

Harmonization of regulatory requirements began as a trade-driven initiative in the European Economic Community (now the European Union [EU]) in the late 1970s. Its purpose was to develop a single body of pharmaceutical legislation and regulations among its member countries. Initiatives that arose out of this desire for harmonization will be discussed in this section and include:

- International Conference of Drug Regulatory Authorities (ICDRA)

- International Council for Harmonization (ICH)

- Pharmaceutical Inspection Co-operation Scheme (PIC/S)

- East African Community (EAC)

- Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN)

- International Coalition of Medicines Regulatory Authorities (ICMRA)

- WHO Collaborative Registration Procedure (WHO CRP)

- Zambia, Zimbabwe, Botswana, and Namibia (ZaZiBoNa)

- International Pharmaceutical Regulators Programme (IPRP)

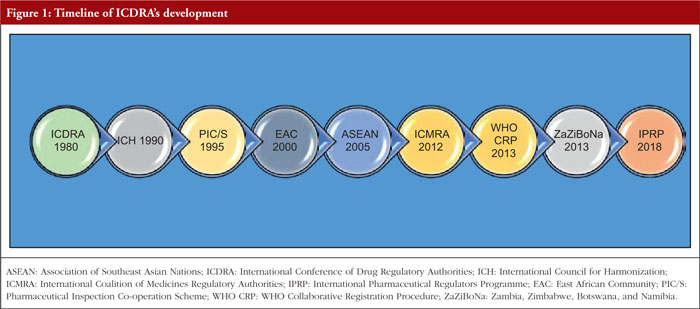

Figure 1 illustrates the timeline of the ICDRA’s establishment and evolution from 1980 through 2018, culminating in the formation of IPRP.

International Conference of Drug Regulatory Authorities (ICDRA)

The ICDRA was established in 1980 as a platform to develop international consensus and provides drug regulatory authorities of WHO Member States with a forum to meet and discuss ways to strengthen collaboration. The ICDRAs have been instrumental in guiding regulatory authorities, WHO and interested stakeholders in determining priorities for action in the national and international regulation of medicines, vaccines, biomedicines and herbals. The conferences have been held since 1980 to promote the exchange of information and collaborative approaches to issues of common concern. As a platform established to develop international consensus, the ICDRA continues to be an important tool for WHO and drug regulatory authorities in their efforts to harmonize regulation and improve the safety, efficacy and quality of medicines. Regulatory authorities are continually faced with new issues – such as globalization and the extension of free trade – while increased responsibilities from market expansion and the improvement and sophistication of products place heavy demands on regulatory systems and knowledge bases. The development of cutting-edge technologies and healthcare techniques, along with the extensive use of the Internet, imposes further complex challenges, such as data privacy and security, misinformation, access inequality, overload of information, regulation and compliance, cybersecurity threats, and integration with existing systems. The ICDRA programme is developed by a planning committee of representative drug regulators. Topics discussed during the four days of the ICDRA may include quality issues, herbal medicines, homoeopathy, regulatory reform, medicines safety, counterfeiting, access, regulation of clinical trials, harmonization, new technologies and e-commerce. Recommendations are proposed for action among agencies, WHO, and related institutions.

International Council for Harmonization (ICH)

ICH was founded in 1990 with the aim of harmonizing the interpretation and application of technical guidelines in the assessment of human medicinal products, serving as the basis for drug approval and minimizing duplication during development and approval.

The birth of ICH took place at a meeting in April 1990, hosted by European Federation of Pharmaceutical Industries and Associations (EFPIA) in Brussels, Belgium. At this meeting, representatives of the regulatory agencies and industry associations from Europe, Japan, and the US met primarily to plan an International Conference on Harmonization, but they also discussed the wider implications and terms of reference of ICH. The ICH initiative had remarkably contributed by establishing a common technical dossier for the submission of product applications for marketing authorization and has also provided several technical guidelines to improve the efficiency of the National Medicines Regulatory Authorities (NMRAs), thereby speeding up the approval process.

The founding regulatory members of ICH include the European Commission, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), and Japan’s Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (MHLW)/ Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency (PMDA). The three geographical regions – the European Union, the United States, and Japan – were the originators of ICH. The purpose of ICH is to promote public health through international harmonization of technical requirements that contribute to the timely introduction of new medicines and continued availability of the approved medicines to patients. It aims to prevent unnecessary duplication of clinical trials in humans and to facilitate the development, registration, and manufacturing of safe, effective, and high-quality medicines efficiently and cost-effectively, while minimizing the use of animal testing without compromising safety and effectiveness.

ICH provides guidelines and standards to ensure the quality, safety, and efficacy (QSE) of drugs. It facilitates the harmonization of regulatory requirements across different regions rather than serving as a regulatory requirement itself. The ICH is an exceptional commission that brings together drug regulatory experts and pharmaceutical business partners from various countries, including the European Union, Japan, and the United States, to harmonize the technical requirements for the use of drugs in humans. The ICH’s requirements pertain to several scientific and technical exchange negotiations related to testing procedures, ensuring the quality, safety, and efficacy of drugs.

ICH offers numerous guidelines categorized under quality, safety, efficacy, and multidisciplinary guidelines. These guidelines contribute to a distinct role in cases involving patient population and large-scale human clinical trials. ICH is an international non-profit organization that was established as an association under Swiss law in October 2015.

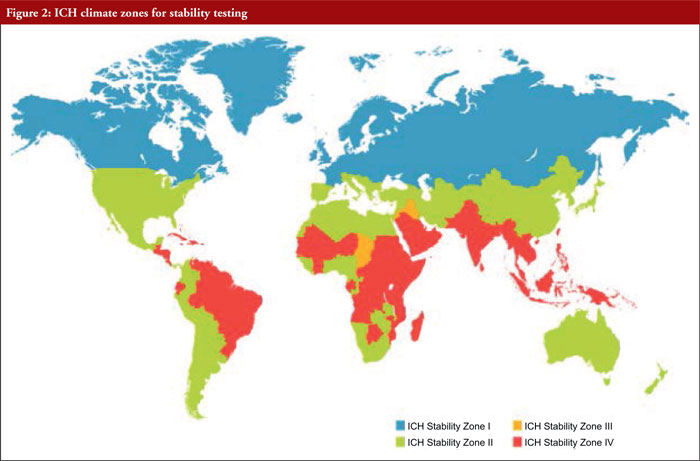

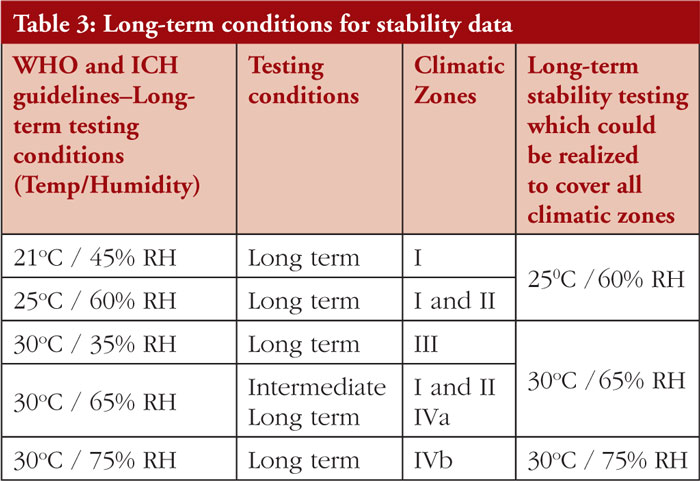

ICH quality guidelines for stability testing take into consideration four climatic zones, namely (see Figure 2):

– Zone I

– Zone II

– Zone III

– Zone IV

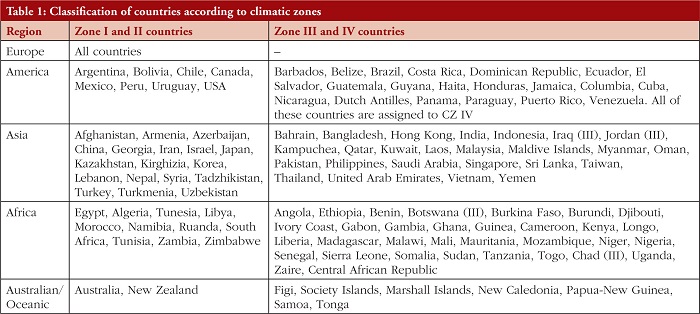

Table 1 provides information on the classification of countries according to climatic zones.

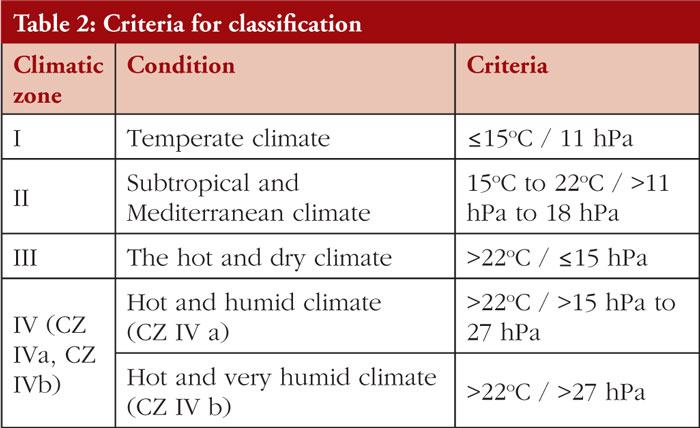

These different climatic zones refer to stability conditions, including temperature, Mediterranean/subtropical, hot dry, hot humid/tropical, and hot and higher humidity zones.

Climatic zones are defined and given by WHO in 2009. The classification criteria were based on the mean annual temperature measured in open air and the mean annual partial pressure of water, see Table 2.

The stability requirements for Climatic Zones I and II are well established and defined in ICH guidelines Q1A, while the stability requirements for Climatic Zones III and IV are not properly outlined due to divergences in their stability requirements so no global harmonization on long-term conditions was reached, see Table 3.

Pharmaceutical Inspection Co-operation Scheme (PIC/S)

PIC/S was established in 1995 as an extension to the Pharmaceutical Inspection Convention (PIC) of 1970. The Pharmaceutical Inspection Co-operation Scheme (PIC/S) is a non-binding, informal co-operative arrangement between regulatory authorities in the field of good manufacturing practice (GMP) for medicinal products intended for human or veterinary use. It is open to any authority with a comparable GMP inspection system. Currently, PIC/S comprises 54 participating authorities coming from all over the world, including Europe, Africa, America, Asia, and Australasia [3].

PIC/S aims to harmonize inspection procedures globally by developing common standards in GMP and providing training opportunities for Inspectors. It also seeks to facilitate cooperation and networking between competent authorities and regional and international organizations, thereby increasing mutual confidence. This mission is reflected in PIC/S’ goal to lead the international development, implementation, and maintenance of harmonized GMP standards and quality systems of inspectorates in the field of medicinal products.

This is to be achieved by developing and promoting harmonized GMP standards and guidance documents; training competent authorities, particularly Inspectors; assessing (and reassessing) inspectorates; and facilitating cooperation and networking among competent authorities and international organizations.

East African Community (EAC)

The East African Community (EAC) is a regional intergovernmental organization in East Africa with a membership of eight states: Democratic Republic of the Congo, Federal Republic of Somalia, the Republics of Burundi, Kenya, Rwanda, South Sudan, Tanzania, and Uganda, with its headquarters in Arusha, Tanzania [4]. The EAC is home to 177 million citizens, of which over 22% are part of the urban population. With a land area of 2.5 million square kilometers and a combined Gross Domestic Product of US$193 billion (EAC Statistics for 2019), its realization bears great strategic and geopolitical significance, along with prospects for a renewed and reinvigorated EAC [5]. The work of the EAC is guided by its Treaty, which established the Community. It was signed on 30 November 1999 and entered into force on 7 July 2000 following its ratification by the original three Partner States: Kenya, Tanzania, and Uganda. The Republic of Rwanda and the Republic of Burundi acceded to the EAC Treaty on 18 June 2007 and became full members of the Community on 1 July 2007. The Republic of South Sudan acceded to the Treaty on 15 April 2016 and became a full member on 15 August 2016.

As one of the fastest-growing regional economic blocs in the world, the EAC is widening and deepening cooperation among the Partner States in various key spheres for their mutual benefit. These spheres include political, economic and social aspects. Currently, the regional integration process is in full swing, as reflected in the encouraging progress of the East African Customs Union, the establishment of the Common Market in 2010, and the implementation of the East African Monetary Union Protocol.

Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN)

ASEAN MRA Taskforce and Signing ASEAN Sectoral MRA on GMP inspection

The ASEAN was founded in 1967 and is comprised of 10 ASEAN Member States (AMS), which have very diverse racial, religious, sociocultural, political, economic, and geographical backgrounds. Each of these 10 AMS faces strong economic competition from other Asian countries and the world at large, especially from those with larger geographical areas and populations, such as South Korea (51 million), Japan (122 million), and the two Asian giants, India (1.4 billion) and China (1.4 billion). Additionally, further away in the western world, there are the US (346 million) and the EU (449 million). However, collectively as a 10-member group, ASEAN is not small.

ASEAN inspectorates are aware that no regulatory authority in this globalized world can work in isolation. The way forward is collaboration, collaboration, and MORE collaboration with ALL stakeholders for a win-win-win outcome: a win for these regulators, a win for the industry, and a win for patients!

A key strength of ASEAN is its combined population (and potential collective market) of approximately 673 million. ASEAN has a combined economy of more than US$3.6 in 2022 trillion and is set to become the fourth-largest world economy by 2030. This collective strength was first optimized through the creation of an ASEAN Economic Community (AEC) on 31 December 2015.

Forming ASEAN MRA Taskforce and Signing ASEAN Sectoral MRA on GMP Inspection

In tandem with the creation of AEC, an ASEAN Mutual Recognition Arrangement (MRA) Taskforce on GMP Inspection was formed in 2005. This Taskforce, with Singapore and Malaysia, respectively appointed as Chair and Vice-Chair, was charged with the key responsibility of delivering an ASEAN Sectoral MRA on GMP Inspection for Manufacturers of Medicinal Products. After four years of intensive face-to-face and online discussions, the Taskforce delivered this legally binding Sectoral MRA on GMP Inspection, which was signed by the Economic Ministers of all 10 AMS in Thailand in April 2009. With the signing of this MRA, the 10 AMS embarked on a journey to recognize one another’s GMP Certificates and inspection reports, thereby avoiding duplication of GMP inspection in each other’s territories.

The ASEAN MRA on GMP Inspection is benchmarked to the international framework of the Pharmaceutical Inspection Co-operation Scheme (PIC/S). The MRA covers all medicinal products in finished dosage forms, and its 19 articles include Article 4 (Scope) and Article 8 (Obligations) of the AMS. Article 4 (Scope) stipulates that the MRA encompasses medicinal products in finished dosage forms (both prescription medicines and over-the-counter [OTC] products) but excludes active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs), biologicals, radiopharmaceuticals, and traditional medicines. Article 8 (Obligations) states that AMS are obliged to operate a PIC/S-equivalent GMP inspection framework and to accept and recognize the GMP Certificates and/or inspection reports issued by ASEAN Listed Inspection Services (LIS), which are inspection services or inspectorates of AMS that have met the technical requirements of the PIC/S framework. A grace period of three years from the year of the signing of the MRA in 2009 required all AMS to establish a PIC/S-equivalent GMP inspection framework by 2012.

International Coalition of Medicines Regulatory Authorities (ICMRA)

The proposal to create an ICMRA is anchored in the recognition that leadership from the Heads of Agency (HoA) is needed to address current and emerging regulatory and safety challenges in human medicine globally, strategically, and in an ongoing, transparent, authoritative, and institutional manner. In May 2012, prior to the 65th World Health Assembly in Geneva, more than 30 medicines regulatory authorities participated in a seminar promoted by Brazil, aimed at stimulating a debate among health officials and the diplomatic community on how to improve cooperation among these authorities. The discussion highlighted the importance of better promoting and coordinating international cooperation among medicines regulatory authorities to strengthen dialogue, facilitate the wider exchange of reliable and comparable information, encourage greater leveraging of the resources and work products of other authorities, and promote a more informed, risk-based allocation of resources. These efforts would strengthen the quality, safety, and efficacy of medicinal products globally [6].

These discussions were held at meetings of senior executives of several medicines regulatory authorities during the International Conference of Drug Regulatory Authorities (ICDRA) in October 2012, and at the 7th Heads of Medicines Regulatory Agencies Summit in Manaus, Brazil in December 2012. As a result, a consensus has emerged on the desirability of developing an ICMRA to address common issues, such as (but not limited to):

i. Growing complexity in manufacturing and distribution supply chains for the medicinal product (multi-faceted and globally integrated)

ii. Regulator’s ability to ensure the safety, quality and efficacy of medicinal products domestically requires knowledge of and confidence in these supply chains

iii. Gaps in global regulatory oversight providing opportunities for the tampering and counterfeiting of medicinal products

iv. Growing complexity in medicinal products and their ingredients (e.g. new chemical entities and innovative drugs) generating new scientific and regulatory challenges which call for new regulatory processes

v. Growing number of international regulatory initiatives, lacking integration and strategic oversight

vi. Continued pressures to control and reduce regulatory public expenditures

vii. Continued industry and political pressures to harmonize and align regulatory practices and activities.

ICMRA provides a global architecture to support enhanced communication, information sharing, crisis response, and to address regulatory science issues.

WHO Collaborative Procedure for Accelerated Registration Procedure

WHO launched its collaborative procedure for accelerated registration of prequalified finished pharmaceutical products (FPPs) in 2013. This procedure accelerates registration by enhancing information sharing between WHO prequalification and national regulatory authorities (NRAs) [7].

In many countries with limited regulatory resources, the registration of FPPs that are WHO-prequalified or approved by stringent regulatory authorities can take a considerable time. In the worst cases, this time can extend to two or three years, meaning that patients may not receive treatment that could save their lives or improve their health. WHO has responded to this situation:

i. Firstly, by creating a collaborative procedure to facilitate the assessment and accelerated national registration of WHO-prequalified pharmaceutical FPPs

ii. Secondly, by creating a collaborative procedure to accelerate the registration of FPPs that have already received approval from a stringent regulatory authority.

The procedure for stringently approved FPPs was drafted taking into account the experience gained during the development, testing, and implementation of the procedure for prequalified FPPs. Thus, while the procedure for prequalified FPPs is fully operational, the procedure for stringently approved FPPs is still in its pilot phase.

In addition to aiming to ensure that much-needed medicines reach patients more quickly, both procedures incorporate strong capacity-building and regulatory harmonization elements. The success of applying both procedures is highly dependent on the ability and willingness of pharmaceutical companies (the applicants), regulatory authorities, and WHO to work together to meet public health goals.

In 2021, WHO published two guidelines namely: Good Reliance Practices/GRelP (Annex 10 of TRS 1033) and Good Regulatory Practices (Annex 11 of TRS 1033). These guidelines provide recommendations to the NMRAs to leverage the outputs of others whenever possible while placing greater focus on value-added regulatory activities at the national level.

ZaZiBoNa

The ZaZiBoNa collaborative medicines registration initiative was established in 2013 by four countries: Zambia, Zimbabwe, Botswana, and Namibia, with technical support from the WHO Prequalification Team (PQT). The acronym ZaZiBoNa was derived from the first two letters of the founding countries. Although the initiative has expanded beyond these four countries, the name ZaZiBoNa has been maintained because of its special meaning in Nyanja, one of the local Zambian languages: ‘look to the future’.

The initiative was formed to address common challenges faced by the participating countries such as huge backlogs of product applications, high staff turnover, long registration times, inadequate financial resources, and limited capacity to assess certain types of products, such as biologicals and biosimilars. Acknowledging these common challenges, the heads of agencies agreed to develop a work-sharing arrangement to achieve objectives that included reducing workload, shortening registration timelines, fostering mutual trust and confidence in regulatory collaboration, and providing a platform for training and collaboration in other regulatory fields. In establishing these objectives, the ZaZiBoNa initiative sought to make efficient use of limited resources to ensure timely access to quality-assured medicines for the public in the Southern African Development Community (SADC) region while simultaneously building the regulatory capacity of the NRAs.

The collaborative initiative began with the first assessment session, held in Windhoek, Namibia in October 2013. These assessments initially looked at applications common to the four countries that were pending in the backlog but expanded over time to review products submitted prospectively. In 2014, the ZaZiBoNa initiative was formally endorsed and adopted by the SADC Ministers of Health. Since then, the initiative has grown, and 13 of the 16 SADC Member Countries are participating either as active or non-active participants, based on their internal capacity to conduct assessments and inspections. The ZaZiBoNa initiative was later absorbed by the SADC Medicines Registration Harmonization (MRH) project, which was launched in 2015 and funded by the World Bank from 2018 to 2020. In addition to strengthening and expanding areas of technical cooperation among member NRAs through initiatives such as ZaZiBoNa, the objectives of the SADC MRH project also include:

– to ensure that at least 80% of Member States have NMRAs that meet minimum standards,

– to ensure regional harmonization of medicines regulatory systems and guidelines,

– to facilitate capacity building of medicines regulatory authorities in Member States through the implementation of quality management systems (QMS)

– to develop and implement national and regional integrated information management systems (IMS) to facilitate decision-making and sharing of knowledge among Member States and stakeholders.

Various activities are currently ongoing to fulfil these objectives. For example, most SADC countries have conducted self-benchmarking of their regulatory systems using the WHO Global Benchmarking Tool (GBT). In addition to existing SADC guidelines, regional guidelines for variations and biosimilars are under development, and an audit of skills in the region is also being conducted using the WHO global competence framework for regulators.

ZaZiBoNa is a collaborative procedure for 14 SADC countries in which national regulatory authorities jointly assess medicines for registration purposes. Currently, five of the 14 Member States actively participating: Zambia, Zimbabwe, Botswana, Namibia, and South Africa. The remaining nine Member States do not actively participate in dossier assessment but are involved in training programmes and information sharing on products approved through the collaborative procedure. In the long term, all SADC countries are expected to participate actively, depending on their capacity. There is mutual agreement, and consent is given by applicants for sharing information concerning the products being considered. When a product has been approved by ZaZiBoNa, it means that it has attained marketing authorization in all the participating countries. Applicants who wish to participate in ZaZiBoNa should have applied for registration of a medicine in at least two of the participating countries and should submit an expression of interest to any of the countries to which the application has been made.

International Pharmaceutical Regulators Programme (IPRP)

In January 2018, the two international initiatives–the ‘International Pharmaceutical Regulators Forum (IPRF) ’ and the ‘International Generic Drug Regulators Programme (IGDRP) ’ – were unified and now function under the name ‘International Pharmaceutical Regulators Programme (IPRP) ’.

IPRP serves as an international platform for its regulatory members and observers, with the following goals:

i. Exchange of information and experiences

ii. Discussion of topics that are of mutual interest, especially new scientific technologies and regulatory challenges

iii. Promoting a consistent implementation of ICH guidelines

iv. Promotion of a possible approximation of regulatory requirements.

In cooperation with the IPRP members, Swissmedic will promote the alignment of regulatory requirements for new chemical and biologically active substances, as well as generics (known active substances). Swissmedic aims to address urgent regulatory issues, harmonize activities, and facilitate the exchange experiences. Swissmedic is actively involved in all IPRP working groups:

– Quality Working Group for Generics

– Bioequivalence Working Group for Generics

– Information Sharing Working Group for Generics

– Biosimilars Working Group

– Nanomedicines Working Group

– Gene therapy Working Group

– Cell therapy Working Group

– Identification of Medicinal Products (IDMP) Working Group.

Besides the international initiatives on regulatory harmonization as mentioned above, several regional and bilateral agreements have begun to take place to minimize duplication of efforts, as follows:

Latin America

Although there is no strict regulatory harmonization among Latin American countries under a unified framework for regulatory reliance and recognition, efforts are currently being made towards greater harmonization to leverage the work done by these countries and minimize duplication. Specifically, efforts are underway to align regulations and guidelines by adopting internationally accepted frameworks such as ICH to expedite the product approval process. Latin American countries are also working to enhance harmonization through Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) by sharing information and developing common pharmacopoeia [8]. Additionally, discussions are taking place in the region to rely fully or partially on approval decisions made by the European Medicines Agency (EMA) and FDA. While countries like Argentina, Colombia, Mexico, and Peru are now accepting certificates issued by EMA and FDA, Brazil still carries out its inspections.

In addition to the initiatives on reliance and harmonization mentioned above, some inspectorates from Latin American countries are joining forces with international inspection authorities. In 2016, Brazil became the first Latin American country to join the ICH as a member, while Cuba, Mexico, and Colombia became the observers.

The National Institute of Drugs in Argentina (Instituto Nacional de Medicamentos, INAME) became the PIC/S participating authority in January 2008. INAME was the first regulatory authority from Latin American to gain accession to PIC/S. Similarly, in 2018, the Federal Commission for the Protection Against Sanitary Risks (Comisión Federal para la Protección contra Riesgos Sanitarios, COFEPRIS) became the second national regulatory authority from Latin America to join PIC/S [9].

From 1 January 2021, the Brazilian National Health Surveillance Agency, (Agência Nacional de Vigilância Sanitária, ANVISA), became the latest participating authority of PIC/S from Latin America.

Beyond the above initiatives, Argentina, Brazil, Colombia, and Cuba are entering into cooperation agreements related to inspections and market recalls, sharing information to avoid duplication of work and expedite market access. Another example of regulatory harmonization is the 2016 agreement signed between Brazil ’s ANVISA and the United States Pharmacopeia (USP) to cooperate on harmonizing pharmacopoeia and minimizing duplication of work.

Access Consortium

The Access Consortium is a collaborative initiative among like-minded, medium-sized regulatory authorities, including Australia ’s Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA), Health Canada (HC), Singapore ’s Health Sciences Authority (HSA), Switzerland ’s Swiss Agency for Therapeutic Products (Swissmedic), and the United Kingdom ’s Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Authority (MHRA). These regulatory authorities face similar challenges, such as increased workload and complexities in the medicinal applications they regulate, contributing to growing pressure on available resources. The Consortium aims to build synergies and share knowledge among the regulatory authorities, thereby enhancing the efficiency of regulatory systems.

The Access Consortium comprises of several working groups with various objectives and projects aimed at helping regulatory authorities address, including ensuring timely access to safe therapeutic products within a limited resource capacity. These working groups operate through a network of bilateral confidentiality agreements and Memoranda of Understanding.

The Consortium explores opportunities for information-sharing and work-sharing initiatives in areas including:

– assessing therapeutic product manufacturing sites

– post-market surveillance of therapeutic product safety

– assessment reports for medicinal products

– development of technical guidelines and regulatory standards

– collaboration on information technology (IT).

The MHRA officially began working with Consortium partners as a full member on 1 January 2021, following a period of shadowing.

The exchange of confidential information aligns with the provisions of existing agreements and complies with each agency ’s legislative framework for sharing such information with other regulatory authorities.

Bilateral Mutual Recognition Agreements (Singapore HSA vs Australia TGA)

On 1 January 2000, Singapore became the first Asian member of the PIC/S. One of the significant advantages of this membership was the signing of the bilateral Singapore-Australia Mutual Recognition Agreement (MRA) on GMP inspection in February 2001. The agreement was facilitated by the PIC/S membership of both Australia and Singapore. Under this MRA, Australia ’s TGA no longer needs to send its GMP auditors to inspect manufacturers in Singapore, and vice versa. More than 15 pharmaceutical companies in Singapore, along with many more in Australia, have benefited from this agreement.

European Union Mutual Recognition Agreements (MRAs) with third-country authorities

The European Union (EU) has signed Mutual Recognition Agreements (MRAs) with third-country authorities regarding the conformity assessment of regulated products. These agreements include a sectoral annex on the mutual recognition of good manufacturing practice (GMP) inspections and batch certification of human and veterinary medicines [10]. MRAs enable EU authorities and their counterparts to:

- rely on each other ’s GMP inspection system

- share information on inspections and quality defects

- waive batch testing of products on import into their territories.

Each agreement has a different scope. MRAs are trade agreements designed to facilitate market access and encourage greater international harmonization of compliance standards, all while protecting consumer safety.

These agreements benefit regulatory authorities by reducing the duplication of inspections in each other ’s territory, allowing for a greater focus on sites that could pose a higher risk and broadening the inspection coverage of the global supply chain. They also facilitate trade in pharmaceuticals by reducing costs for manufacturers through a decrease in the number of inspections conducted at facilities and by waiving the re-testing of their products upon importation.

European Medicines Agency

The European Commission is responsible for negotiating MRAs with partner countries on behalf of the EU. The European Commission may consult EMA on regulatory and scientific questions as part of this process. EMA is involved in operational activities once the MRAs are in place, including:

- facilitating cooperation on inspections, including joint inspections and exchange of information on inspections

- facilitating the exchange of information and being the relevant contact point between the EU GMP inspectorates and partner authorities

- operating the EudraGMDP database and connecting partners countries to it

- responding to queries on the implementation of the MRA

- involving partners countries in relevant EMA working groups, such as the GMP/Good-distribution-practice Inspectors Working Group

- coordinating MRA maintenance activities.

Recommendations

Based on the available initiatives on reliance approaches, the author would like to offer the following recommendations:

– WHO published guidance on Good Reliance Practices in the regulation of medical products in 2021. It provides high-level principles and considerations for national regulatory authorities (NRAs) regarding reliance work as a general principle to make the best use of available resources. NRAs should consider following abridged regulatory pathways to save time and resources and expedite approvals, rather than adhering to standard pathways. The principles and considerations presented in this document should be taken into account when implementing regulatory reliance frameworks or strategies. Effective implementation of reliance will benefit not only NRAs but also patients, healthcare providers, and the industry.

– WHO has also published guidance on Good Regulatory Practices (GRP) in the regulation of medical products in 2021. GRP is defined as a set of principles and practices applied to the development, implementation, and review of regulatory instruments (laws, regulations, and guidelines) to achieve public health objectives most efficiently. GRP provides a means of establishing and implementing sound, affordable, and efficient regulation of medical products, which is an important part of health system performance and sustainability.

– WHO published a guideline on Good Practices of National Regulatory Authorities in implementing the collaborative registration procedures (CRP) for medical products in 2019. This guideline is intended to serve as a model for NRAs ’ best practices in implementing CRP and reliance and/or risk-based approaches within their overall marketing authorization systems for medical products. It describes the practical steps NRAs should take to implement the CRP for WHO Prequalified Products, SRA-approved products, and products from other reference authorities and regional collaborative procedures.

– WHO has published a Collaborative procedure between the World Health Organization Prequalification Team and national regulatory authorities for the assessment and accelerated national registration of WHO-prequalified pharmaceutical products and vaccines.

– In addition, WHO has published another guidance on Good Pharmacopoeial Practices. The primary objective of this guidance is to define approaches and policies for establishing pharmacopoeial standards, with the ultimate goal of harmonization. The guidance describes a set of principles that provide direction for national pharmacopoeial authorities (NPAs) and regional pharmacopoeial authorities (RPAs), facilitating the appropriate design, development, and maintenance of pharmacopoeial standards.

Conclusion

This paper reviews the history of the regulatory reliance and recognition initiatives, reflecting what has been accomplished with current harmonization activities and what still needs to be achieved.

The author supports the idea of regulatory reliance and recognition proposed by various international, regional, and national regulatory authorities and organizations. Mutual recognition and reliance will not only help the regulatory authorities expedite the product approval process, but manufacturers will also benefit from receiving fewer on-site inspections, which are often duplicated in nature.

Looking at the current regulatory harmonization initiatives, it is important to strengthen regulatory systems by increasing efficiency through reliance and recognition programmes. Such strengthening initiatives will certainly improve the supply of therapeutics, vaccines, and other health products.

Finally, it is recommended that matured regulatory authorities (previously referred to as stringent regulatory authorities) and international organizations should work hand-in-hand with regional and national regulatory authorities by proactively exchanging information on product assessment, on-site inspections, and post-marketing approvals (also known as variations) to reduce the time to market approval.

Competing interests: None.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

1. World Health Organization. TRS 1033 – Annex 10: Good reliance practices in the regulation of medical products: high level principles and considerations [homepage on the Internet]. [cited 2024 Oct 28]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/annex-10-trs-1033

2. World Health Organization. TRS 1019 – Annex 6: Good practices of national regulatory authorities in implementing the collaborative registration procedures for medical products [homepage on the Internet]. [cited 2024 Oct 28]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/annex-6-trs-1019

3. Pharmaceutical Inspection Co-operation Scheme [homepage on the Internet]. [cited 2024 Oct 28]. Available from: https://picscheme.org/

4. East African Community [homepage on the Internet]. [cited 2024 Oct 28]. Available from: https://www.eac.int

5. East African Community. East African Community facts and fi gures 2019 [homepage on the Internet]. [cited 2024 Oct 28]. Available from: https://www.eac.int/component/documentmananger/?task=download.document&fi le=bWFpbl9kb2N1bWVudHNfcGRmX0V2cFVzSHl3RUF6dUhnS2hXc3RkVkRNRUFDIEZhY3RzIEZpZ3VyZXMgMjAxOQ==&counter=575

6. International Coalition of Medicines Regulatory Authorities. History of ICMRA [homepage on the Internet]. [cited 2024 Oct 28]. Available from: https://icmra.info/drupal/en/aboutus/history

7. World Health Organization. Collaborative procedure for accelerated registration [homepage on the Internet]. [cited 2024 Oct 28]. Available from: https://extranet.who.int/pqweb/medicines/collaborative-procedure-accelerated-registration

8. Pan American Health Organization, IRIS. Regulatory system strengthening in the Americas [homepage on the Internet]. [cited 2024 Oct 28]. Available from: https://iris.paho.org/bitstream/handle/10665.2/53793/9789275123447_eng.pdf

9. Pharmaceutical Inspection Co-operation Scheme. Members [homepage on the Internet]. [cited 2024 Oct 28]. Available from: https://picscheme.org/en/members?paysselect=MX7

10. European Medicines Agency. Mutual recognition agreements (MRA) [homepage on the Internet]. [cited 2024 Oct 28]. Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/human-regulatory/research-development/compliance/good-manufacturing-practice/mutual-recognition-agreements-mra

|

Author: Vimal Sachdeva, MSc, Technical Offi cer (Senior Inspector), Inspection Services, Prequalifi cation Unit, Regulation and Prequalifi cation Department, Access to Medicines and Health Products Division, World Health Organization, 20 Avenue Appia, CH-1211, Geneva 27, Switzerland |

Disclosure of Conflict of Interest Statement is available upon request.

Copyright © 2024 Pro Pharma Communications International

Permission granted to reproduce for personal and non-commercial use only. All other reproduction, copy or reprinting of all or part of any ‘Content’ found on this website is strictly prohibited without the prior consent of the publisher. Contact the publisher to obtain permission before redistributing.