European payer initiatives to reduce prescribing costs through use of generics

Published on 2012/02/21

Generics and Biosimilars Initiative Journal (GaBI Journal). 2012;1(1):22-7.

Author byline as per print journal: Brian Godman1,2,3, BSc, PhD; Bjorn Wettermark1,4, MSc, PhD; Iain Bishop5, BSc; Thomas Burkhardt6, MSc; Jurij Fürst7, PhD; Kristina Garuoliene8, MD; Ott Laius9, MScPharm; Jaana E Martikainen10, Lic Sc(Pharm); Catherine Sermet11, MD; Inês Teixeira12, BA, MSc; Corrine Zara13, PharmD; Lars L Gustafsson1, MD, PhD

| Introduction: Pharmaceutical expenditure is increasingly scrutinised by payers of health care in view of its rapid growth resulting in a variety of reforms to help moderate future growth. This includes measures across Europe to enhance the utilisation of generics at low prices. Methods: A narrative review of the extensive number of publications and associated references from the co-authors was conducted, supplemented with known internal health authority or web-based articles. Results: Each European country has instigated different approaches to generic pricing, which can be categorised into three groups, with market forces in Sweden and UK lowering the prices of generics to between 3–13% of pre-patent loss originator prices. Payers have also instigated measures to enhance the utilisation of generics versus originators and patent-protected products in a class or related class. These can be categorised under the 4Es: education, engineering, economics and enforcement, with the measures appearing additive. The combination of low prices for generics coupled with measures to enhance their utilisation has resulted in appreciable cost savings in some European countries with expenditure stable or decreasing alongside increased utilisation of products in a class. Conclusion: Reforms will increase as resource pressures continue to grow with the pace of implementation being likely to accelerate. Care though with the introduction of prescribing restrictions to maximise savings as outcomes may be different from expectations. |

Submitted: 7 April 2011; Revised manuscript received: 15 October 2011; Accepted: 19 October 2011

Introduction

Pharmaceutical expenditure is increasingly scrutinised by payers in view of its rapid growth, outstripping growth in other components of health care [1-7]. This growth has resulted in pharmaceutical expenditure in ambulatory care becoming the largest, or equal to the largest, cost component in this sector [1, 3-9], with expenditure on drugs in ambulatory care typically appreciably greater than inpatient drug costs, particularly in Europe. This growth in pharmaceutical expenditure has been driven by well-known factors including changing demographics, rising patient expectations, strict clinical outcome targets, and the continued launch of new and expensive drugs [1, 3, 5, 6, 10].

As a consequence, third-party payers have introduced multiple reforms and initiatives in recent years to optimise the managed entry of new drugs and, in addition, to help control expenditure on existing drugs through encouraging the increased prescribing of generics at low prices [1, 2, 6, 7, 11-13]. The various measures to increase the prescribing of generics among existing molecules and classes, as well as their potential impact, will be appraised in this review article. A list of potential, additional measures that third-party payers could introduce as they seek further measures to help control their rising prescribing costs is also provided.

This review will be divided into two sections: firstly, the measures that have been instigated to lower the prices of generics; secondly, measures to enhance their utilisation. However, we acknowledge that there will be overlap between these two sections. The principal focus will be on Europe.

Pricing policies to help lower the pr ice of generics in Europe

Each European country has introduced different measures to lower the price of generics. However, the variety of measures can be categorised into three distinct approaches [1, 3, 4, 8, 11, 14-17]:

• Prescriptive pricing policies: mandated price reductions for reimbursement, e.g. under the ‘stepped price’ model in Norway, there is an automatic 30% price reduction for the first generic versus the originator pre-patent loss prices, which increases to 55% or 75% reduction six months later depending on overall expenditure. There is a maximum 85% reduction for high expenditure generics after a further 12 months. In France, generics currently have to be 55% below pre-patent loss originator prices to be reimbursed, with further price reductions in subsequent years.

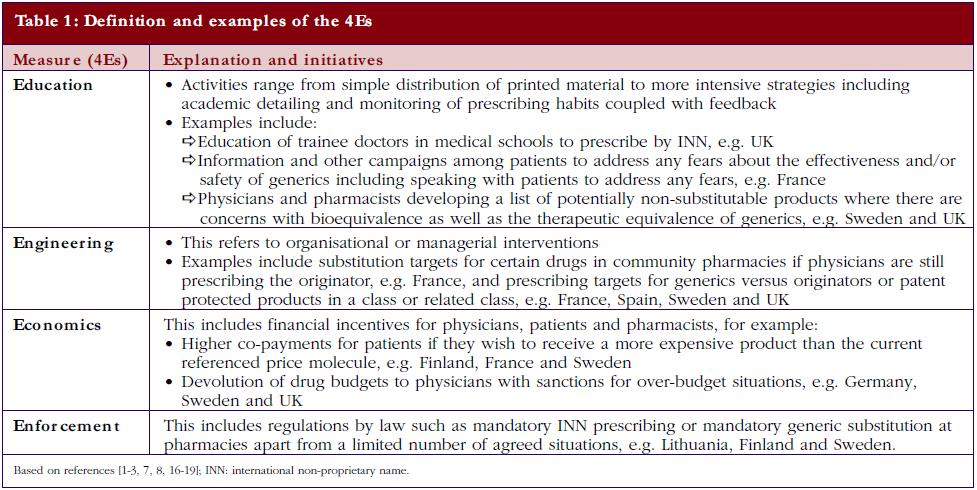

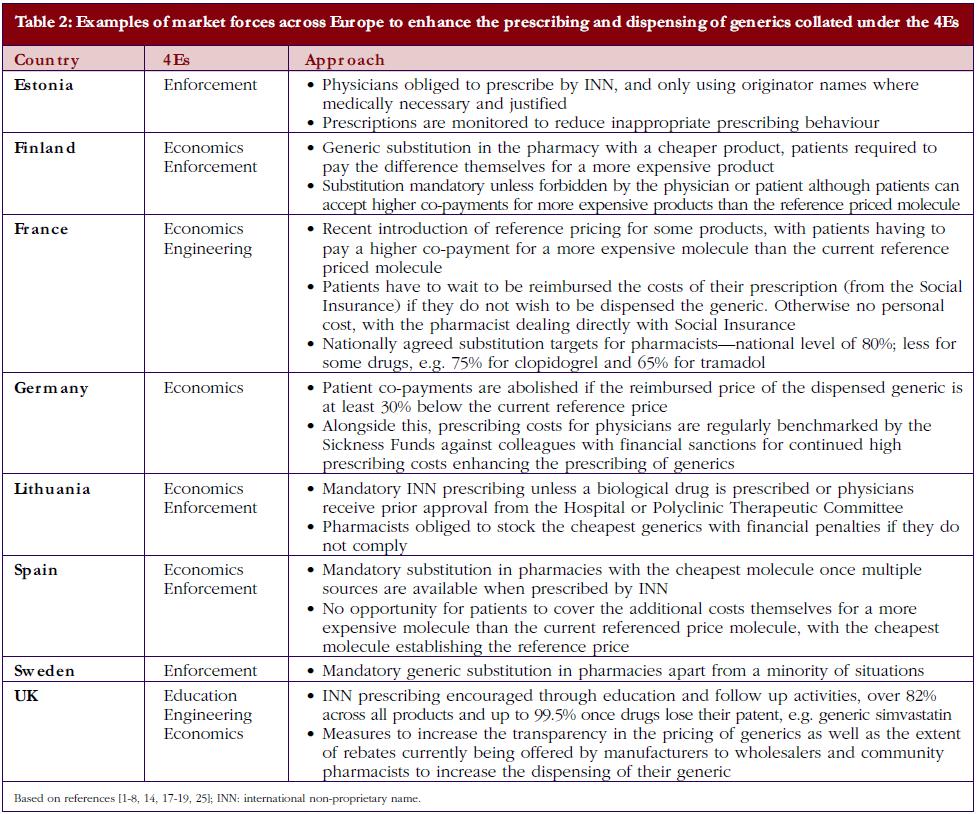

• Market forces: market forces are used in a number of European countries to lower the price of generics. This is achieved by introducing a variety of demand-side measures that encourage the prescribing and dispensing of generics versus originator molecules, as well as lowering their prices. Market forces can be categorised by the 4Es: namely education, engineering, economics and enforcement. Table 1 gives the definition of each category alongside examples, with Table 2 documenting examples of initiatives to enhance the prescribing and dispensing of generics versus originators among European countries with different methods of financing health care, geographies, and epidemiology.

• Mixed approach: a combination of prescriptive pricing for the first generic(s) with market forces after that, e.g. in Austria the first generic must be priced 48% below pre-patent loss originator prices to be reimbursed, second generic 15% below the first generic and the third generic 10% below the second (overall 60% below pre-patent loss prices). Market forces to further lower prices from the fourth generic onwards, with each new generic necessarily priced lower than the last one for reimbursement and physicians financially incentivised to prescribe the cheapest branded generic(s). In Finland, the price of the first generic must be 40% lower than the pre-patent originator price to be reimbursed. Prices of subsequent generics must not be higher than the first generic for reimbursement with market forces, including the need for additional co-payment for more expensive products than the reference priced molecule, helping to reduce prices.

These are in addition to compulsory price cuts for both originators and generics instigated among some European countries as they struggle to contain rising pharmaceutical expenditure [1, 3, 5, 8, 9].

The different approaches to the pricing of generics has led to an appreciable variation in reimbursed prices for generics across countries, with prices varying up to 36-fold depending on the molecule [3, 20].

However, the general trend is for countries to introduce additional measures to lower their generics prices to maximise savings with countries continuing to learn from each other [3, 5, 8], introducing initiatives highlighted in Table 1. For instance, high volume generics in Sweden and UK are priced at between 3–13% of pre-patent loss prices through a variety of market force measures, some of which are highlighted in Table 2 [3, 7, 14, 21]. This is driven by global sales of products likely to lose their patents between 2008 and 2013 estimated at US$50 –US$100 billion (Euros 35 – Euros 70 billion) per year [22, 23], with global sales of pharmaceuticals estimated at US$820 billion (Euros 579 billion) in 2009 [24].

Demand-side measures to enhance the prescribing of generics

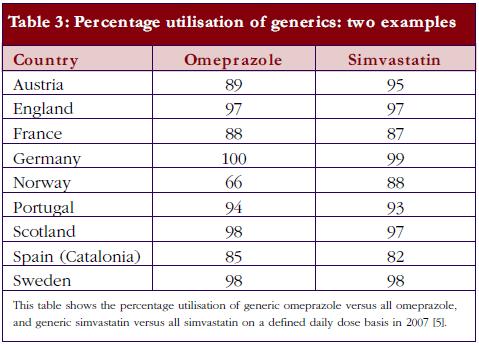

Currently, there is also an appreciable variation in the utilisation of generics across Europe. This includes the prescribing and dispensing of generics versus originators, as well as the prescribing of generics versus patent-protected products in a class or related classes. Table 2 contains examples of ongoing demand-side measures across Europe to enhance the prescribing and dispensing of generics versus originators, which resulted in high utilisation rates for generic omeprazole versus the originator and generic simvastatin versus the originator in 2007 in a recent cross-national study, see Table 3; full details of the measures undertaken to increase the utilisation of generics in individual European countries can be found in references 3 and 5.

European countries have also introduced a variety of different measures to encourage the prescribing of generics within a class. The objective is again to take advantage of the availability of lower priced generics in a class. As a result, these measures help fund increased drug volumes and new drugs without having to raise taxes or health insurance premiums. However, recent research has shown that among the proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), 3-hydroxy-3-methil-gluteryl-CoA reductase inhibitors (statins) and renin-angiotensin products, there is considerable variation in the prescribing of generics within a class or related classes once generics become available in a class [5, 8, 15, 26, 27]. Consequently, there are appreciable opportunities for countries to further enhance their prescribing of generics and lower their prescribing costs through learning from each other.

Examples of ongoing initiatives to increase the prescribing of generic products in a class, again broken down by the 4Es building on Tables 1 and 2, include [1, 4-8, 14-17, 27-29]:

• Educational activities: local, regional and national formularies coupled with monitoring of prescribing patterns and academic detailing. One example is the ‘Wise Drug’ list in Stockholm County Council, which contains approximately 200 drugs covering conditions typically encountered in ambulatory care. Prescribing suggestions typically include older well-established and well-documented drugs, which are generally available as generics, rather than newly marketed drugs. Physician-prescribing patterns are continually benchmarked against the list and their colleagues to enhance adherence to the guidance, with the instigation of educational activities if needed.

• Engineering activities: a number of European countries have instigated prescribing targets. These typically include the percentage of generic drugs within a class such as the percentage of generic PPIs versus all PPIs, percentage of generic statins versus all statins and percentage of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs) versus all rennin-angiotensin drugs.

• Economic interventions: financial incentives to physicians for achieving agreed prescribing targets in a class, as well as devolution of drug budgets to local general practitioner groups combined with regular monitoring of prescribing behaviour.

• Enforcement: prescribing restrictions such as restricting the prescribing of patent-protected statins to second-line in Austria, Finland, Norway, and Sweden as well as restricting the prescribing of angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) to second-line in Austria and Croatia.

However, in countries with less intensive demand-side measures to combat industry and other pressures to prescribe patent-protected drugs, there is typically an increased prescribing of patent-protected products once multiple sources are available. Examples include increased prescribing of esomeprazole with decreased prescribing of omeprazole as a % of total PPI utilisation, which has been seen in France, Ireland, and Portugal [5, 8]. The reverse was seen in countries that have instigated multiple and intensive demand-side measures such as Spain (Catalonia), Sweden, and UK. A similar situation was seen with the statins, with increased utilisation of atorvastatin and rosuvastatin and decreased utilisation of simvastatin in countries with less intensive demand-side measures, with the exception of Portugal where the utilisation of all three statins increased following the availability of generic simvastatin [5, 8].

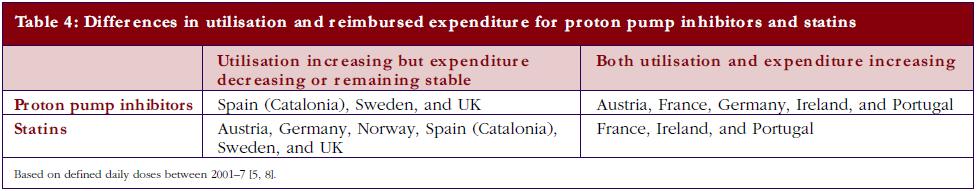

The differences in price that can be obtained for generics in countries, coupled with measures to enhance their prescribing versus originators as well as patent protected products in a class, can have a profound impact on overall prescribing costs. Table 4 documents changes in reimbursed expenditure between 2001 and 2007 among western European countries for both PPIs and statins alongside changes in their utilisation [5, 8]. The introduction of reference pricing for both PPIs and statins in Germany appreciably increased the utilisation of omeprazole and simvastatin at the expense of esomeprazole and atorvastatin [5, 19, 25]. However, higher expenditure/defined daily doses for generic omeprazole and generic simvastatin compared with Sweden and UK limited efficiency gains in practice [30, 31].

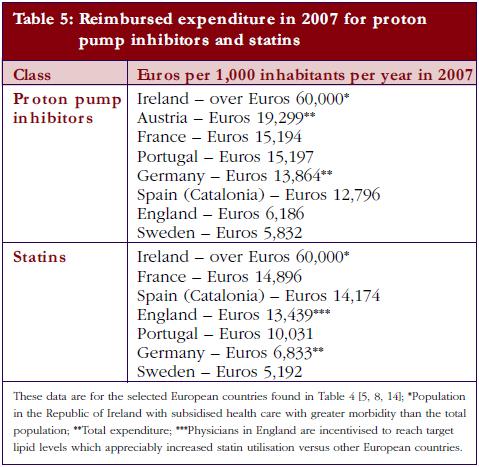

The different patterns seen in Table 4 resulted in appreciable differences in overall expenditure for the PPIs and statins among European countries in 2007 when adjusted for population sizes, see Table 5.

The quality of care does not appear to be compromised through initiatives to enhance the utilisation of generics. This demonstrates the potential of releasing considerable resources through the increased use of generics, see Table 5, without negatively affecting outcomes. This is further illustrated by health authorities and health insurance agencies typically viewing all PPIs as having similar effectiveness based on available data [5-8, 14, 19, 25]. They also generally believe generic statins can be used as first-line to treat patients with coronary heart disease and hypercholesterolaemia adequately, with patent-protected atorvastatin and rosuvastatin reserved for patients failing to achieve target lipid levels with, e.g. generic simvastatin [5-8, 11, 14, 15, 17, 19, 25]. These beliefs are endorsed by a recent ecological study, which showed that outcomes, in terms of the subsequent impact of drug treatment on lipid levels, were similar whether patients were prescribed formulary drugs (including generic simvastatin) versus non-formulary drugs, which included patent-protected statins [32]. Published studies have also shown that patients can be successfully switched from atorvastatin to simvastatin without compromising care [33], and physicians in UK extensively prescribe generic simvastatin to achieve agreed target lipid levels in the quality and outcomes framework to help maximise their income [14, 21, 34, 35]. Alongside this, pharmaceutical companies have failed to provide reimbursement agencies with any published studies documenting increased effectiveness of ARBs versus ACEIs to support premium prices for ARBs [26, 27]. In addition, only 2–3% of patients in the ACEI clinical trials actually discontinued ACEIs due to coughing [36, 37], and a recent ecological study again showed that outcomes, in terms of the subsequent impact of drug treatment on blood pressure, were similar whether patients were prescribed formulary drugs (including generic ACEIs) versus non-formulary drugs, which included patent-protected ARBs [32]. As a result, generic ACEIs can be prescribed first line with patent-protected ARBs reserved for patients where there are concerns with side effects without compromising outcomes.

Finally, care may be needed when considering the introduction of prescribing restrictions (enforcement). This is because their nature and follow-up appear to influence subsequent utilisation patterns appreciably [4, 15, 17, 26]. For instance, the prescribing restrictions for patent-protected statins, atorvastatin and rosuvastatin, had less influence on increasing the utilisation of generic statins, e.g. simvastatin, in Norway versus Austria and Finland. This was the result of having no prior authorisation scheme in Norway, unlike Austria, or no close scrutiny over prescriptions as seen in Finland [4, 15, 17]. In Austria, atorvastatin and rosuvastatin can only be reimbursed if physicians obtain agreement from the Chief Medical Officer of the patient’s Social Health Insurance Fund [4]. The Norwegian authorities also recently introduced prescribing restrictions for esomeprazole. However, hospital specialists in Norway have to verify the diagnosis and recommend therapy before PPIs are reimbursed, and they are not subject to the same restrictions [15]. This reduced the influence of the prescribing restriction in practice, with physicians generally reluctant to deviate from the initially prescribed drug or the advice for the prescription if this was for esomeprazole [15].

Conclusion

The differences between the extent and intensity of supply- and demand-side measures encouraging the prescribing of generics at low prices led to over tenfold difference in reimbursed expenditure for the PPIs and statins in 2007 between European countries when adjusted for populations, see Table 5. However, there was greater morbidity among the Irish population studied [5, 8]. Consequently, there are considerable opportunities for countries to learn from each other to reduce their prescribing costs, especially with the influence of demand-side measures appearing additive.

Both supply- and demand-side measures are thought to be important to limit costs, with countries limiting the extent of any potential efficiency gain if they principally concentrate on one set of measures. For example, in Germany, the reimbursed prices for generics are appreciably higher than seen in UK, which limited potential savings in reality [38]. The limited number of demand-side measures in Portugal also reduced their efficiency gains from recent initiatives to lower generic prices [3, 5, 8]. This is changing with recent reforms. However, payers are urged to consider the nature of any prescribing restrictions they may seek to introduce, and their follow-up, when they forecast the possible influence of these measures, as there could be appreciable differences from expectations [15, 26, 27].

We are already seeing countries learning from each other to identify new initiatives to enhance their prescribing efficiency, i.e. increased drug utilisation at similar or lower costs. Examples include greater transparency in the pricing of generics, prescribing targets, physicians’ financial incentives, compulsory prescribing with the international non-proprietary name, and prescribing restrictions [1, 3, 5, 6, 8, 18]. It is likely that the pace of implementation of what has been learned will accelerate to maintain the European ideals of universal, affordable, and comprehensive health care, especially given the current financial concerns coupled with ongoing pressures. This will need to be reviewed in future publications.

For patients

The costs of health care are rising across Europe through ageing populations resulting in greater prevalence of patients with chronic diseases, stricter clinical targets for managing patients with long term (chronic) diseases, the continued launch of new and more expensive drugs as well as rising patient expectations. The provision of generics (multiple sourced products once the original product loses its patent) at considerably lower prices than the price of the originator just before it lost its patent, and with similar effectiveness and safety to the originator through strict licensing regulations, allows European governments to continue to provide comprehensive and equitable health care without prohibitive increases in either taxes or health insurance premiums. This paper discusses a number of measures introduced by health authorities or health insurance companies in recent years to increase the prescribing and dispensing of generics, with countries continuing to learn from each other as cost pressures continue growing.

Disclosure of financial interest

The majority of the authors are employed directly by health authorities or health insurance agencies or are advisers to these organisations. No author has any other relevant affiliation or financial involvement with any organisation or entity with a financial interest, in or financial conflict with, the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript.

This study was in part supported by grants from the Karolinska Institutet.

Acknowledgement

We acknowledge the help of INFARMED with providing NHS data on Portugal.

Author and co-authors

1Department of Laboratory Medicine, Division of Clinical Pharmacology, Karolinska Institutet, Karolinska University Hospital Huddinge, SE-14186, Stockholm, Sweden

2Prescribing Research Group, University of Liverpool Management School, Chatham Street, Liverpool L69 7ZH, UK

3Institute for Pharmacological Research Mario Negri, 19 Via Giuseppe La Masa, IT-20156 Milan, Italy

4Public Healthcare Services Committee, Stockholm County Council, Sweden

5Information Services Healthcare Information Group, NHS Scotland, 1 South Gyle Crescent, Edinburgh EH12 9EB, UK

6Hauptverband der Österreichischen Sozialversicherungsträger, 21 Kundmanngasse, AT-1031 Wien, Austria

7Health Insurance Institute, 24 Miklosiceva, SI-1507 Ljubljana, Slovenia

8Medicines Reimbursement Department, National Health Insurance Fund, 1 Europas a, LT-03505 Vilnius, Lithuania

9State Agency of Medicines, 1 Nooruse, EE-50411 Tartu, Estonia

10Research Department, The Social Insurance Institution, PO Box 450, FI-00101 Helsinki, Finland

11IRDES, 10 rue Vauvenargues, FR-75018 Paris, France

12CEFAR – Center for Health Evaluation and Research, National Association of Pharmacies (ANF), 1 Rua Marechal Saldanha, PT-1249-069 Lisbon, Portugal

13Barcelona Health Region, Catalan Health Service, 30 Esteve Terrades, ES-08023 Barcelona, Spain

References

1. Sermet C, Andrieu V, Godman B, et al. Ongoing pharmaceutical reforms in France; implications for key stakeholder groups. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2010;8:7-24.

2. Wettermark B, Godman B, Andersson K, et al. Recent national and regional drug reforms in Sweden – implications for pharmaceutical companies in Europe. Pharmacoeconomics. 2008;26:537-50.

3. Godman B, Shrank W, Wettermark B, Andersen M, et al. Use of generics – a critical cost containment measure for all healthcare professionals in Europe? Pharmaceuticals. 2010; 3:2470-94. doi 10.3390/ph/3082470

4. Godman B, Burkhardt T, Bucsics A, et al. Impact of recent reforms in Austria on utilisation and expenditure of PPIs and lipid lowering drugs; implications for the future. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2009;9:475-84.

5. Godman B, Shrank W, Andersen M, et al. Comparing policies to enhance prescribing efficiency in Europe through increasing generic utilisation: changes seen and global implications. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2010;10:707-22.

6. Coma A, Zara C, Godman B, et al. Policies to enhance the efficiency of prescribing in the Spanish Catalan Region: impact and future direction. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2009;9:569-81.

7. Godman B, Wettermark B, Hoffman M, et al. Multifaceted national and regional drug reforms and initiatives in ambulatory care in Sweden; global relevance. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2009;9:65-83.

8. Godman B, Shrank W, Andersen M, et al. Policies to enhance prescribing efficiency in Europe: findings and future implications. Front Pharmacol. 2011;1(141):1-16. doi:10.3389/fphar.2010.00141

9. Barry M, Usher C, Tilson L. Public drug expenditure in the Republic of Ireland. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2010;10:239-45.

10. Garattini S, Bertele V, Godman B, et al. Enhancing the rational use of new medicines across European healthcare systems: a position paper. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2008; 64(12):1137-8.

11. Godman B, Burkhardt T, Bucsics A, et al. Impact of recent reforms in Austria on utilisation and expenditure of PPIs and lipid lowering drugs; implications for the future. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2009;9:475-84.

12. Wettermark B, Godman B, Eriksson C, van Ganse E, Garattini S, Joppi R, et al. Einführung neuer arzneimittel in europäische gesundheitssysteme GGW 2010; Jg.10, Heft 3: 24-34 [Introduction of new medicines into European healthcare systems – abstract in English]. Available from: www.wido.de/fileadmin/wido/downloads/pdf_ggw/wido_ggw_aufs3_0710.pdf

13. Wettermark B, Persson ME, Wilking N, et al. Forecasting drug utilization andexpenditure in a metropolitan health region. BMC Health Serv Res. 2010;10:128.

14. McGinn D, Godman B, Lonsdale J, et al. Initiatives to enhance the efficiency of statin and proton pump inhibitor prescribing in the UK; impact and implications. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2010;10:73-85.

15. Godman B, Sakshaug S, Berg C, et al. Combination of prescribing restrictions and aggressive generic pricing policies – an alternative approach to conserve resources? Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2011;11:121-9.

16. Wettermark B, Godman B, Jacobsson B, Haaijer-Ruskamp F. Soft regulations in pharmaceutical policymaking – an overview of current approaches and their consequences. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2009;7(3):137-47.

17. Martikainen JE, Saastamoinen LK, Korhonen MJ, et al. Impact of restricted reimbursement on the use of statins in Finland – a register-based study. Medical Care. 2010;48:761-6.

18. Garuoliene K, Godman, B, Gulbinovic J, et al. European countries with small populations cannot obtain low prices for drugs – Lithuania as a case history to contradict this. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2011;11:341-7.

19. Godman B, Schwabe U, Selke G, Wettermark B. Update of recent reforms in Germany to enhance the quality and efficiency of prescribing of proton pump inhibitors and lipid-lowering drugs. Pharmacoeconomics. 2009;27:1-4.

20. Simoens S. International comparison of generic medicine prices. Current 2007;23(11):2647-54.

21. Bennie M, Godman B, Bishop I, Campbell S. Multiple initiatives continue to enhance the prescribing efficiency for the proton pump inhibitors and statins in Scotland. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. Forthcoming 2012;12(1).

22. Frank R. The ongoing regulation of generic drugs. N Engl J M. 2007;357:1993-6.

23. Jack A. Balancing Big Pharma’s books. BMJ. 2008;336:418-9.

24. EATG. 2009 world pharma sales forecast to top $820 billion. [cited 2011 Dec 11]. Available from: http://www.eatg.org/eatg/Global-HIV-News/Pharma-Industry/2009-world-pharma-sales-forecast-to-top-820-billion

25. Godman B, Haycox A, Schwabe U, et al. Having your cake and eating it: Office of Fair Trading proposal for funding new drugs to benefit patients and innovative companies. Pharmacoeconomics. 2008;26:91-8.

26. Godman B, Bucsics A, Burkhardt T, et al. Initiatives to enhance renin-angiotensin prescribing efficiency in Austria: impact and implications for other countries. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2010;10:199-207.

27. Voncina L, Godman B, Vlahovic-Palcevski V, Bennie M. Recent policies to enhance renin-angiotensin prescribing efficiency in Europe; implications for the future. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2011;20:S210.

28. Gustafsson LL, Wettermark B, Godman B, et al. The “Wise List”- a comprehensive concept to select, communicate and achieve adherence to recommendations of essential drugs in ambulatory care in Stockholm. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2011;108(4):224-33.

29. Wettermark B, Godman B, Neovius M, Hedberg N, et al. Initial effects of a reimbursement restriction to improve the cost-effectiveness of antihypertensive treatment. Health Policy. 2010;94:221-9.

30. Godman B, Wettermark B. Impact of reforms to enhance the quality and efficiency of statin prescribing across 20 European countries. In: Webb D, Maxwell S, editors. 9th Congress EACPT 2009; 65-69. Medimond International Proceedings – Medimond s.t.l.Rastignano (BO), Italy. Volume: ISBN 978-88-7587-548-0; CD: ISBN 978-88-7587-549-7.

31. Godman B, Wettermark B. Trends in consumption and expenditure of proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) in 20 European countries. In: Webb D, Maxwell S, editors. 9th Congress EACPT 2009; 71-75. Medimond International Proceedings- Medimond s.t.l. Rastignano (BO), Italy. Volume: ISBN 978-88-7587-548-0; CD: ISBN 978-88-7587-549-7.

32. Norman C, Zarrinkoub R, Hasselström J, Godman B, Granath F, Wettermark B. Potential savings without compromising the quality of care. Int J Clin Pract. 2009:63:1320-6.

33. Usher-Smith J, Ramsbottom T, Pearmain H, Kirby M. Evaluation of the clinical outcomes of switching patients from atorvastatin to simvastatin and losartan to candesartan in a primary care setting: 2 years on. Int J Clin Pract. 2008;62:480-4 .

34. Roland M. Linking physicians’ pay to the quality of care – a major experiment in the United Kingdom. N Eng J Med. 2004;351:1448-54.

35. Doran T, Fullwood C, Gravelle H, Reeves D, Kontopantelis E, Hiroeh U, Roland M. Pay-for-performance programs in family practices in the United Kingdom. N Eng J Med. 2006;355:375-84.

36. Fletcher A, Palmer A, Bulpitt C. Coughing with angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors; how much of a problem? J Hypertens. 1994;12:S43-7.

37. Frisk P, Mellgren T-O, Hedberg N, et al. Utilisation of angiotensin blockers in Sweden combining survey and register data to study adherence to prescribing guidelines. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2008;64(12):1223-9.

38. Godman B, Abuelkhair M, Vitry A, Abdu S, et al. Payers endorse generics to enhance prescribing efficiency, impact and future implications. Generics and Biosimilars Initiative Journal. Forthcoming 2012;1(2).

|

Author: Brian Godman, BSc, PhD, Department of Laboratory Medicine, Division of Clinical Pharmacology, Karolinska Institutet, Karolinska University Hospital Huddinge, SE-14186, Stockholm, Sweden |

Disclosure of Conflict of Interest Statement is available upon request.

Permission granted to reproduce for personal and non-commercial use only. All other reproduction, copy or reprinting of all or part of any ‘Content’ found on this website is strictly prohibited without the prior consent of the publisher. Contact the publisher to obtain permission before redistributing.

Related articles

Payers endorse generics to enhance prescribing efficiency: impact and future implications, a case history approach

The impact of pharmaceutical pricing and reimbursement policies on generics uptake: implementation of policy options on generics in 29 European countries─an overview

A review of generic medicine pricing in Europe