Increasing adoption of quality-assured biosimilars to address access challenges in low- and middle-income countries

Published on 2024/05/07

Generics and Biosimilars Initiative Journal (GaBI Journal). 2024;13(2):40-54.

Author byline as per print journal: Pritha Paul1, PhD; Rahul Kapur2*, MBBS, PhD; Shivani Mittra3, MPharm, PhD; Nimish Shah4, JD, MBA; Gopal K Rao1, MSc; Matthew E Erick4, BS, RPh; Susheel Umesh1, BPharm, MBA; Sandeep N Athalye2, MBBS, MD

|

Abstract: |

Submitted: 1 March 2024; Revised: 25 April 2024; Accepted: 27 April 2024; Published online first: 6 May 2024

Introduction

The burden of non-communicable diseases (NCDs) is increasing rapidly across the globe. NCDs cause nearly 75% of all deaths worldwide, and 85% of the people who die yearly due to NCDs are from low- and middle-income countries (LMIC) [1]. The risk of dying prematurely from NCDs in LMICs is almost twice as high as in high-income countries (HICs) [2]. The healthcare budgets are more limited, and the regulatory systems, although evolving, are less developed in LMICs compared to those of HICs, which translates to poor access to life-saving medicines. The disparity in access to essential medicines for NCDs is a plausible contributing factor to a higher number of premature deaths from NCDs in LMICs compared to HICs [3]. Biosimilars can help increase patients’ access and affordability to lifesaving biologic medicines by promoting pricing competition with the originator biologics/reference products (RPs). As most of the literature around biosimilars focuses on HICs, this review article offers insights into the challenges faced for biosimilar uptake and offers recommendations for faster and better access to biosimilars in emerging markets and, more broadly, LMICs. Focusing on data from selected emerging markets (Brazil, Colombia, Malaysia, Mexico, Nigeria, Turkey, and Taiwan), we explored trends in the regulatory framework of biosimilars, potential and actual benefits of biosimilars, and challenges in accessing quality-assured biosimilars. Finally, recommendations to enhance access and use of quality-assured biosimilars in LMICs and a list of potential criteria to help stakeholders in LMICs select these quality-assured biosimilars are also provided.

Methodology

Interviews

Three interviews were conducted with ex-government officials/individuals who had worked with governments in Nigeria, Colombia, and Taiwan to explore the challenges related to access to biosimilars and ways to facilitate the adoption of quality biosimilars.

Recruitment: Participant eligibility was restricted to former government officials/people affiliated with governments and familiar with the reimbursement of biosimilars in Nigeria, Colombia, and Taiwan.

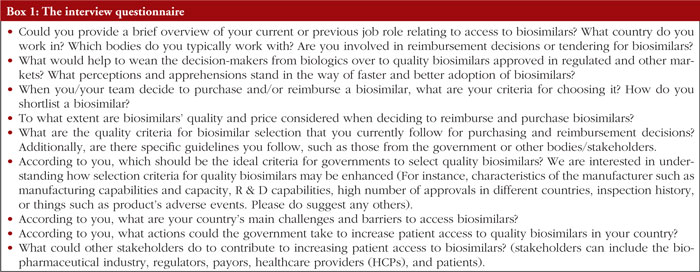

Interview guide: the interview guide included open-ended questions so that the participants could be relatively free to share insights based on their experience, see Box 1.

Interviews: Three interviews were conducted, one in each of the following countries: Nigeria, Colombia, and Taiwan, by Clarivate between February and August 2023, after obtaining consent to collect insights.

Analysis: Content analysis was performed on the transcripts of the interviews to extrapolate insights, and the interviews were summarized to be included in the review.

Literature search

A literature search was conducted to gather insights, focusing on the following emerging markets: Brazil, Colombia, Malaysia, Mexico, Nigeria, Turkey, and Taiwan. These countries, except Taiwan, are middle-income countries (MICs) with varying income levels, ranging from lower- to upper-middle-income countries. Taiwan was included in this search, given its successful move from LMIC to HIC; insights from Taiwan may be relevant for emerging markets that might evolve into HICs in the future. Various sources were analysed, including articles, peer-reviewed papers, and reports. Biocon Biologics Limited (BBL) established the research method and contracted Clarivate to help conduct the interviews and the literature search and draft the review article. BBL reviewed and co-developed the review article.

The burden of NCDs in LMICs and growing interest in biosimilars

NCDs are responsible for the deaths of 41 million people annually, corresponding to 74% of all deaths globally. Every year, 17 million people below the age of 70 die from NCDs. Of these premature deaths, 86% occur in LMICs. Notably, cancer and diabetes are among the most common NCDs, together with cardiovascular and chronic respiratory diseases [1].

NCDs disproportionately affect people in LMICs, where more than three-quarters of all deaths (31.4 million) occur due to NCDs. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), NCDs are a barrier to achieving the United Nations (UN) 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, which, among other objectives, aims to reduce premature mortality (between the ages of 30 and 70) caused by NCDs by one third by 2030 [1].

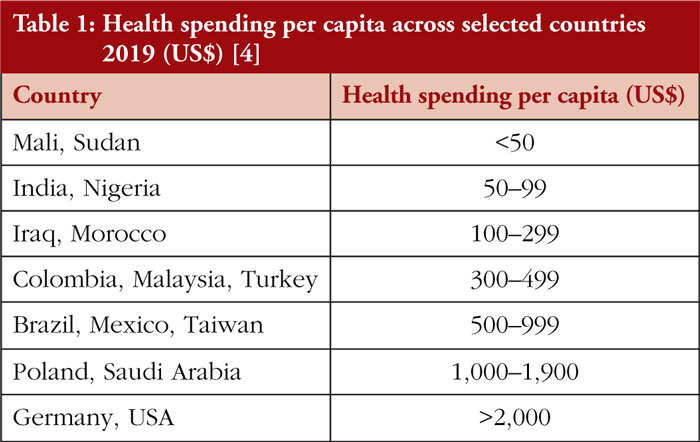

As outlined in Table 1, there is a vast disparity in health spending per capita across countries in the world, with LMICs spending considerably less compared to HICs, see Figure 1. This can contribute to overall poorer health outcomes in LMICs, making access to affordable biosimilars, particularly important.

Biosimilars are increasingly recognized as viable treatment options

The Model List of Essential Medicines of WHO, 2023 requires the inclusion of critical medicines, such as monoclonal antibodies and insulins, ‘to be available in functioning health systems at all times, in appropriate dosage forms, of assured quality and at prices individuals and health systems can afford’ [5]. However, the burden of the cost of anticancer medicines often falls on the patients as an out-of-pocket expense in LMICs and low-income countries (LICs). For instance, the patient bears the cost of 58% of essential cancer medications in LICs, compared to 32% in low-middle-income countries and just 1.8% in upper-middle-income countries [6]. Additionally, some costly treatment options may not even be integrated into national formularies; for example, a recent study published in 2023 reports that by 2019, only 19% of countries had incorporated trastuzumab, a drug required by WHO Model Lists of Essential Medicines 2015, into their formularies [6].

Biologics are large, complex molecules from a living organism or its products. Due to their complexity, it is possible to only develop similar but not identical molecules, ‘biosimilars’, of the originator RP [7]. Biosimilars differ from generics, which can contain medicinal ingredients identical to their RPs. Although the definition of a biosimilar slightly varies across countries, WHO defines it as ‘a biologic product that is shown to be highly similar in terms of its quality, safety, and efficacy to an already licensed reference product’ [8].

Biosimilars offer lower-cost alternatives to their reference products (RPs), promote competition, and can contribute to reducing the prices of RPs. Biosimilars can thus facilitate increased patient access to biologics, contributing to improved patient outcomes and sustainable use of healthcare system resources.

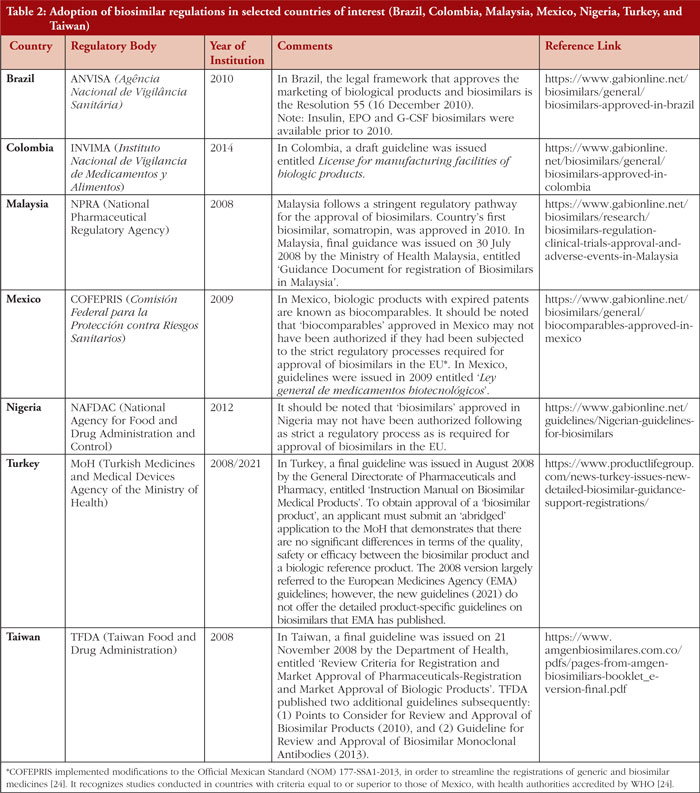

As patents of RPs expire, biosimilars are being approved in various countries. As of June 2021, biosimilars of nine RPs were approved in Taiwan [9]. By July 2020, 30 biosimilars of 13 RPs, 13 biosimilars of four RPs, 96 biosimilars of 20 RPs, 22 biosimilars of 13 RPs, 12 biosimilars of eight RPs, and eight biosimilars of six RPs were approved in Brazil, Ghana, India, Iran, Jordan, Ukraine, respectively [10, 11]. In 2022, biosimilars of at least nine RPs, and four RPs were approved, respectively, in Mexico and Colombia [10, 12, 13]. By October 2023, biosimilars of 16 RPs were approved in Malaysia [14]. The growing number of biologics under development suggests opportunities for increased biosimilar development and use in the future. However, in the LMICs, the quality of the biosimilar or similar biotherapeutic product can be of concern as some of these products were either approved prior to the adoption of regulations or guidelines for biosimilar evaluation or may not have been approved following a strict comparative regulatory process as recommended by the WHO guidelines [11]. Table 2 shows the adoption of biosimilar regulations in selected countries of interest.

How are regulatory frameworks for biosimilars evolving?

Emerging and evolving regulatory frameworks

The European Medicines Agency (EMA) was the first regulatory authority to establish a framework for approving biosimilars, issuing guidelines in 2005 [15]. Since then, various regulatory authorities, including the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), have developed frameworks and guidelines for approving biosimilars.

Regulatory pathways are different for biologic originators (the RP) and biosimilar drugs, with the latter subject to ‘abbreviated clinical development pathways’. Biosimilar development is, in fact, more streamlined and linked to lower costs compared to the development of RPs. Nevertheless, these differences do not imply a difference in the efficacy and safety of biosimilars [16]. Generally, for a biosimilar to be approved, no demonstratable clinically meaningful difference in quality, safety, or efficacy should exist when compared to the RP [17]. Developing a biosimilar involves a stepwise, head-to-head comparison exercise, which starts with analytical assessments of structural and functional attributes of the biosimilar compared with the RP, followed by non-clinical and clinical assessments. The clinical assessments usually involve a pharmacodynamics (PD)/pharmacokinetics (PK) comparison followed by at least one comparative safety and efficacy trial. This comparison exercise aims to establish a high similarity between the biosimilar and its RP [17]. In the last decade, no relevant differences between biosimilars and their respective originators/RPs have been identified via the safety monitoring system in the European Union. None of the approved biosimilars has been withdrawn due to safety or efficacy concerns, thus providing reassurance and validation concerning the biosimilar approval pathway in highly regulated regions [17].

Regulatory frameworks for biosimilars differ among countries. However, WHO is making continuous efforts to increase global regulatory convergence. Ever since the WHO guidelines for the regulatory evaluation of biosimilars were issued in 2009, WHO has worked towards harmonizing the terminology and the regulatory framework for biosimilars globally [11, 18, 19]. WHO describes the progress made and the regulatory landscape changes for biosimilars in 21 countries through a survey carried out in 2019&nadsh;2020 [18, 19]. The following salient points were surmised: (1) WHO guidelines have contributed towards setting the regulatory framework for biosimilars in the countries surveyed and have increased regulatory convergence at the global level; (2) Has made the terminology used for biosimilars more consistent than in the past; (3) Has worked towards biosimilars being approved in all participating countries. Despite this effort, the survey revealed some challenges that still remain: unavailable/insufficient RPs in the the countries surveyed, lack of resources, problems with the quality of some biosimilars, and difficulties with the practice of interchangeability and naming of the biosimilars [19]. The survey also put forth opportunities/solutions for regulatory authorities to manage the challenges faced, namely: (1) exchange of information on products with other regulatory authorities and accepting foreign licensed and sourced reference products, hence avoiding conducting unnecessary (duplicate) bridging studies; (2) use of a ‘reliance’ concept and/or joint review for the assessment and approval of biosimilars; (3) review and reassessment of the products already approved before the establishment of a regulatory framework for biosimilar approval; and (4) setting appropriate regulatory oversight for good pharmacovigilance, which is essential for the identification of problems with products and establishing the safety and efficacy of interchangeability of biosimilars [19].

The new WHO guidelines for biosimilar evaluation published in 2022 include the current data requirements and considerations for licensing biosimilars [20]. The framework for biosimilars in LMICs is continuously evolving, and, like HICs, many LMICs have established abbreviated clinical development pathways for biosimilars’ evaluation, often following the frameworks of WHO and EMA. Despite this step towards facilitating access to biosimilars, comparability pathways for biosimilars are not always implemented effectively in LMICs, due to ambiguity in the regulatory oversight [21].

Many LMICs also rely on WHO’s list of prequalified products to guide their selection of medicines. The WHO Prequalification of Medicines Programme (PQP) is a service to assess medicines’ quality, safety, and efficacy, helping to ensure that procurement agencies supply medicines that meet acceptable standards [22]. This programme has resulted in improved access to two oncology drugs trastuzumab, since 2019, and rituximab, since 2020 in many LMICs [22].

The importance of streamlining development requirements

Although the development cost of biosimilars is lower compared to their RPs, it is still high in absolute terms and much higher compared to generics, due to the complexity of biologic molecules. Waiving off regulatory requirements that might not be strictly essential can thus benefit biosimilar development costs and timelines [23]. According to the WHO guidelines, ‘a comparative efficacy trial may not be necessary if sufficient evidence of biosimilarity can be inferred from other parts of the comparability exercise’ [20]. Guidelines of the FDA, Health Canada, and EMA allow flexibility for phase III ‘confirmatory’ clinical safety and efficacy studies granted that specific essential requirements are met, such as the presence of PD biomarkers as relevant markers or surrogates for efficacy [24]. Similarly, comparative clinical efficacy is not required in the UK, provided a solid scientific rationale exists for this [25].

Regulators in LMICs are also taking steps to streamline the approval process for biosimilars. In September 2023, Brazil’s National Health Surveillance Agency (ANVISA) opened a consultation acknowledging the potential removal of certain studies or steps for biosimilar registration [26]. Similarly, for the registration of biosimilars, the Federal Commission for the Protection against Sanitary Risks (COFEPRIS) of Mexico announced the recognition of studies conducted in countries with criteria equal or superior to those of Mexico (with regulators recognized by WHO as reference regulatory authorities) [27]. With this measure, Mexico is also making progress in the implementation of a harmonization process through which local regulations are aligned with international standards or requirements [27].

The interchangeability debate

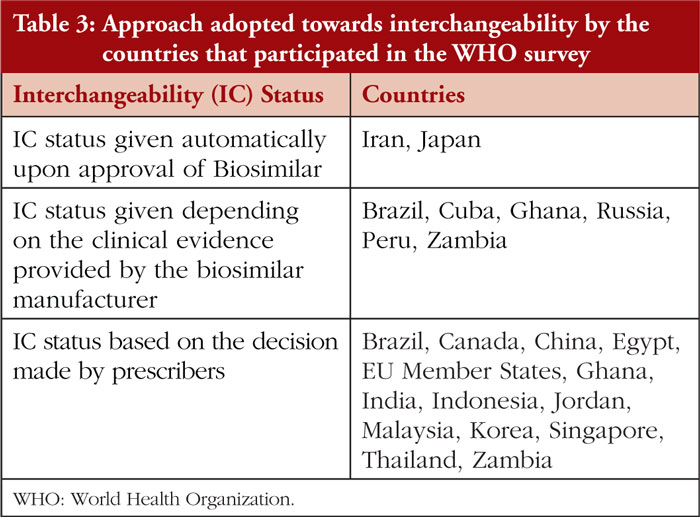

The requirement of interchangeability between an RP and its biosimilar or between two biosimilars highly varies among countries. Interchangeability remains an important yet challenging topic globally, and in LMICs, imprecise use of interchangeability remains an issue [28]. Table 3 provides the approach to the interchangeability status adopted by the countries that participated in the WHO survey [19].

In the concept of interchangeability, one product can be replaced with another by either switching, which is decided by a physician, or by automatic substitution at the pharmacy level. In the US, the biosimilar has to be denoted with an ‘interchangeable product status’ by FDA. Once denoted as an ‘interchangeable biosimilar’ it can be automatically substituted with the reference product at the pharmacy level. FDA determines a biologic product to be interchangeable with a reference product if: (1) the biologic product ‘is biosimilar to the reference product’ and ‘can be expected to produce the same clinical result as the reference product in any given patient’; and (2) ‘for a biologic product that is administered more than once to an individual, the risk in terms of safety or diminished efficacy of alternating or switching between use of the biologic product and the reference product is not greater than the risk of using the reference product without such alternation or switch’ [29]. In a recent development, FDA is considering eliminating interchangeability details from product labels as these are potentially confusing (according to the new draft guidance on biosimilar labelling) [30].

EMA defines interchangeability as ‘the possibility of exchanging one medicine for another that is expected to have the same clinical effect’. This may imply changing an RP with a biosimilar (or the other way round) or a biosimilar with another. Such changes can happen via switching at the prescriber level [31]. There is no official position on interchangeability of a biosimilar at the EU level. Instead, several national regulatory authorities, including the Dutch Medicines Evaluation Board (MEB), the Finnish Medicines Agency (FIMEA), Healthcare Improvement Scotland, the Irish Health Products Regulatory Authority, and Paul-Ehrlich-Institute in Germany, have already taken national positions to endorse the interchangeability of biosimilars under the supervision of the prescriber [32, 33].

The WHO survey of 21 countries revealed that most LMIC countries do not have regulatory guidelines for the interchangeability of biosimilars, but many have adopted national approaches for this. As summarized in Table 3, most of the countries rely on the decisions made by the prescribers. However, Brazil, Cuba, Ghana, Peru, Russia, and Zambia also consider the clinical evidence provided by the biosimilar manufacturers [19].

It is important to note that both biosimilars and interchangeable biosimilars can constitute as safe and effective treatment options. Some prescribers fear that switching between non-identical but highly similar biologics can lead to loss of efficacy or adverse events. However, several reviews have confirmed the safety of switching from RPs to biosimilars. This includes a systematic review of 178 switch studies, encompassing over 20,000 switched patients, reporting no signs of such switching associated with any loss of efficacy or higher rates of side effects [31].

What are some actual and potential benefits of biosimilars?

Success stories from HICs

More data on the benefits of biosimilars for healthcare systems and societies are available in HICs, such as the US and European countries, compared to LMICs.

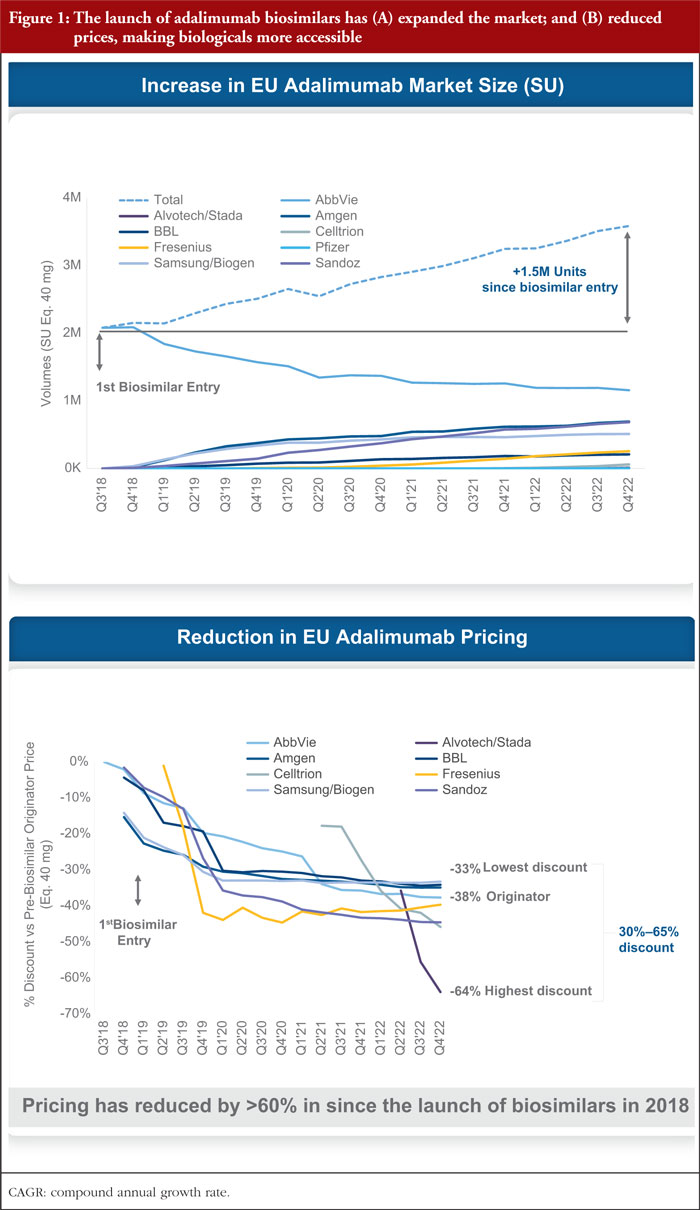

The biosimilar market share has been growing in HICs, with the total European biosimilar market reaching Euros 8.8 billion in 2021 [34]. As of 2022, biosimilar products comprised nearly 66% of the adalimumab share in the EU [35]. Notably, the impact of biosimilar competition led to cumulative savings at list prices of over Euros 30 billion in Europe by 2022 [36]. Figure 1 shows the market expansion and price reduction with the advent of adalimumab biosimilars in the EU.

Significant price reductions have also been associated with the market entry of biosimilars in the US. The cumulative savings in drug spending from the trastuzumab biosimilar launch between Q3 2019 and Q2 2022 was estimated to be US$5.3 billion in the US. Moreover, three years after the launch of the first trastuzumab biosimilar, the price of the RP declined by 19%, and biosimilars accounted for 80% of the share of all trastuzumab products [35].

A 2023 report by the US Department of Health and Human Services highlighted how biosimilar competition reduced costs for Medicare Part B and enrollees. Opportunities remain to further decrease Part B and enrollee expenditure via increased utilization of more affordable biosimilars [37].

Biosimilars are not only linked to cost savings, but they also add value through increased access to medicines for patients. For instance, European data showed a substantial increase in the use of biologics and biosimilars when a biosimilar entered the market, which was attributed to reduced costs driven by competition [38]. Physician perspectives on biosimilars have also positively evolved, as demonstrated by a survey of 63 oncologists and immunologists showing more confidence in using biosimilars across various European countries [39].

Actual and potential benefits of biosimilars for LMICs

Despite more data being available for HICs, promising data on the potential and actual benefits of biosimilars also exists for LMICs.

Biosimilars are more cost-effective treatment options than their RPs and competing with RPs can contribute to decreasing RPs’ prices and allow more patients to be treated. In Malaysia, for instance, insulin prices have dropped over 40%, and insulinization rates have improved by 30% since 2011, when biosimilars to RHI insulins were made available [40].

A study in Brazil estimated the impact of the lack of access to trastuzumab on the mortality of human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-positive (HER2-positive) patients with metastatic tumours in the national health system (NHS) in 2016. Of the 2,008 women diagnosed with advanced HER2-positive breast cancer, it was estimated that two years later, only 808 would be alive if they received only chemotherapy, 1,408 if they received chemotherapy plus trastuzumab, and 1,576 if they received the gold standard of chemotherapy plus trastuzumab and pertuzumab [41]. Studies such as this one underscore the importance of adopting biosimilars in countries with sub-optimal accessibility to life-saving medicines, such as trastuzumab.

A recent study conducted in China confirmed equivalent clinical outcomes and lower prices of cancer care biosimilars compared to RPs, suggesting that increasing the uptake of biosimilars can benefit oncology patients. A systematic review and meta-analysis of 39 randomized clinical trials and 10 cohort studies found equivalent clinical outcomes between rituximab, bevacizumab, and trastuzumab and their RPs in China. In 2022, the estimated median weighted average prices for biosimilars of bevacizumab, rituximab, and trastuzumab in China were 74%, 69%, and 90% of the price of the RP, while biosimilars uptake rates were 83%, 74%, and 54%, respectively [42].

Governments, regulators, and physicians consider biosimilars as important treatment options in emerging markets

In 2014, the Colombian Ministry of Health and Social Protection highlighted that eight of its NHS’s 10 most used medicines were biologics. If there were just two competitors for each of those eight biologics, the Colombian NHS could have saved 600 billion Colombian pesos [43]. In Mexico, the head of COFEPRIS emphasized in 2017 that biosimilars represent a safe option for the NHS to improve access to treatments for NCDs [44].

Many physicians now believe using biosimilars can reduce costs and increase patient’s access to medicines. For instance, according to a survey among Malaysian oncologists, most oncologists (95%) agreed that prescribing a biosimilar would save healthcare costs, increase the accessibility of biologics (91%), and stimulate competition in the biologics market (88%) [45].

What are some barriers to biosimilar access and adoption?

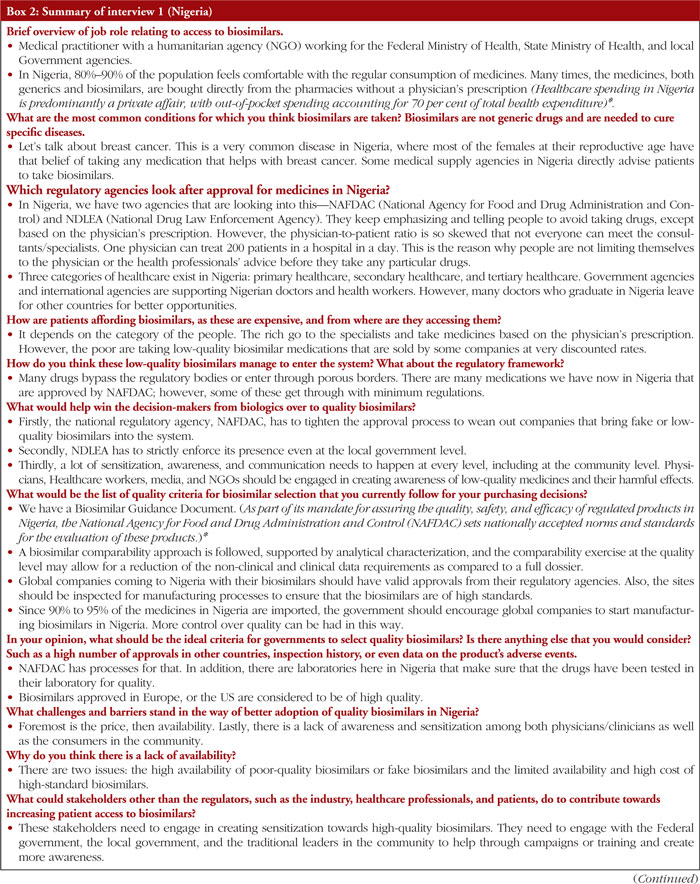

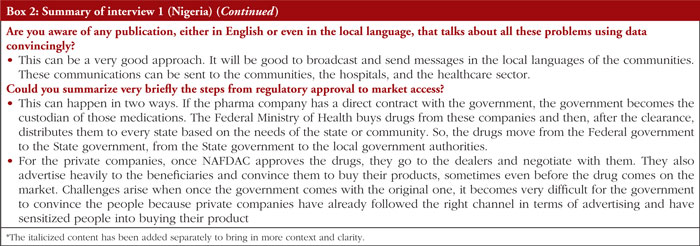

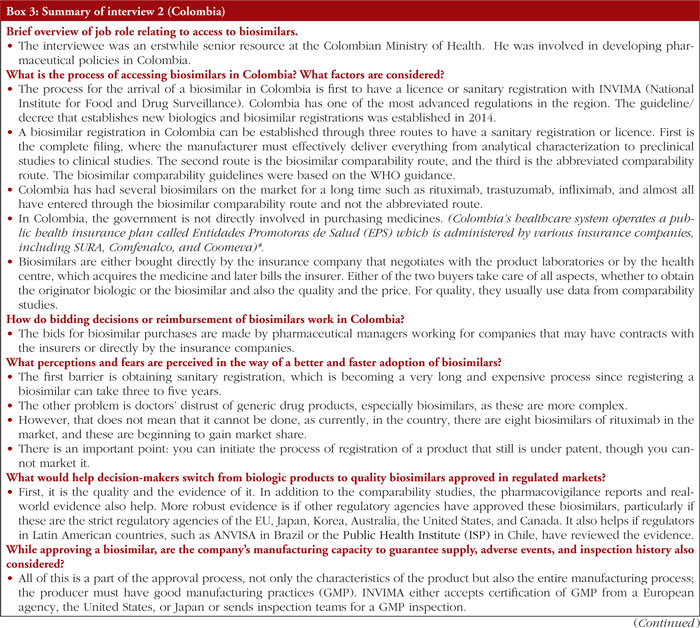

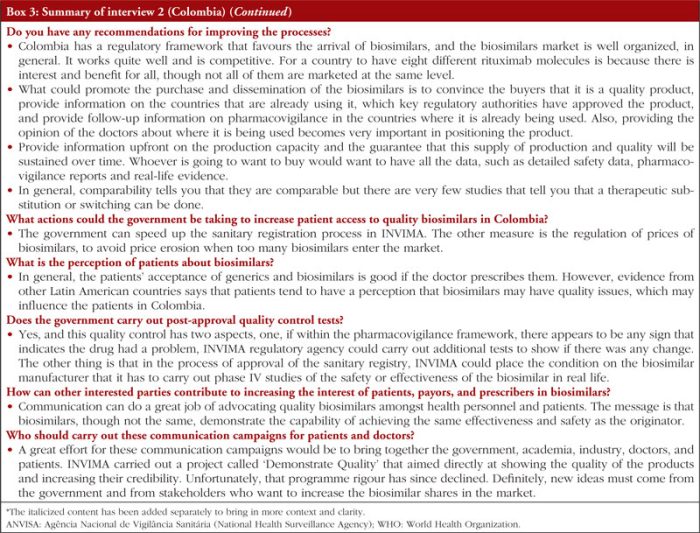

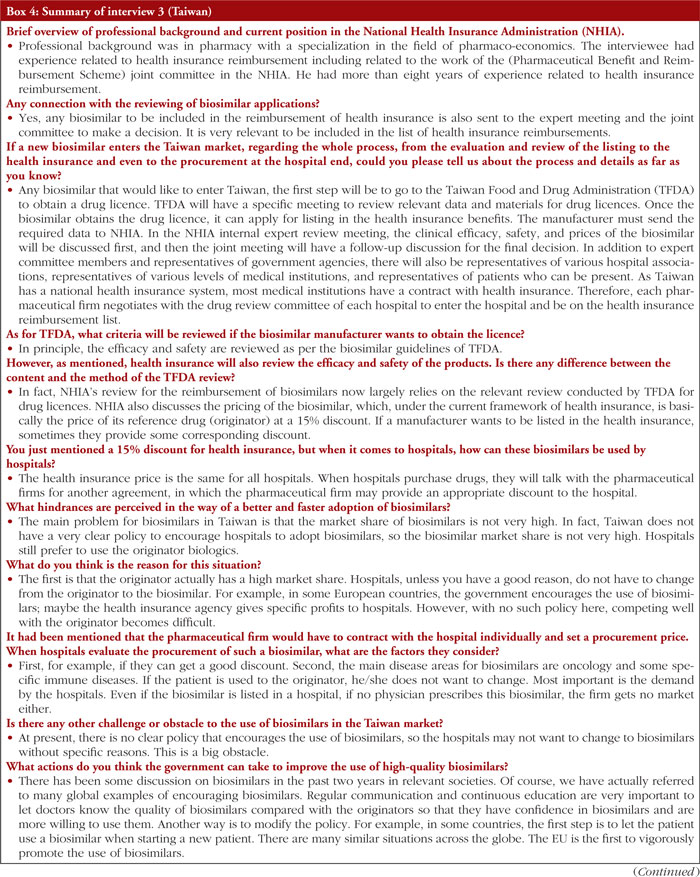

Challenges of various natures remain towards increased access to and adoption of quality-assured biosimilars in emerging markets and, more broadly, in the global South. Insights on key access challenges were gathered mainly via a literature search and were complemented with interviews. A total of three interviewees from three countries, Nigeria (lower-middle-income), Colombia (upper-middle-income), and Taiwan (high-income), were interviewed to gather insights from different local contexts.

Weak regulatory frameworks

Despite progress, regulatory frameworks for biosimilars have different maturity levels across LMICs, with some remaining unclear or under development. Heterogenous regulations, non-adherence to regulatory pathways, and imprecise use of interchangeability (as well as insufficient pharmacovigilance) are common challenges [28]. These factors can impede or slow down access to quality-assured biosimilars. In particular, the African region has the highest prevalence of poor-quality medicines, with weak or absent regulatory systems largely responsible for this [46]. WHO estimates that one in 10 medicines in LMICs is substandard or falsified, with most reports of these products coming from Africa [47]. Unsurprisingly, the Nigerian interviewee flagged abuse and misuse of fake, counterfeit, and low-quality biosimilars. Possible identified causes for this issue included underdeveloped regulatory systems, easy access to cheap but low-quality or fake biosimilars, lack of education on biosimilars, not following the prescribers’ guide, and difficulty securing follow-up appointments with doctors.

Inappropriate labelling of drugs as biosimilars

In LMICs certain non-innovator biotherapeutic products other than the originators or biosimilars are approved and can occupy a substantial proportion of the market. The dominant product class of human insulin, manufactured in various countries, is a key example of such a biotherapeutic.

A me-too/non-innovative/copy biotherapeutic product, i.e. non-originator and non-biosimilar, is defined as a biotherapeutic product developed on its own and not directly compared and analysed using a licensed reference biotherapeutic product as a comparator. It may or may not have been compared clinically. In the WHO survey, the existence of a regulatory framework for such products in the participating countries was assessed [19]. Brazil, China, Cuba, Malaysia, the Republic of Korea, and Thailand have formulated regulations for such products. Brazil had several such products on its market as non-innovator products, and all that were licensed before March 2002 have been reassessed in terms of efficacy and safety for each indication, that is, four somatropins, one filgrastim, one interferon, and two erythropoietins. On the other hand, China has 98 non-innovator biotherapeutics of 13 products approved by the National Regulatory Authority. However, there is no plan for their re-evaluation. These products range from the older ones like interferon and erythropoietin to newer monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) like adalimumab and bevacizumab. The complexity of this situation becomes a barrier to the uptake of biosimilars as it decreases confidence in biosimilar uptake.

Dependence on importation

Given the difficulties in encouraging local manufacturing, many LMICs are highly dependent on importing biosimilars from other countries, making them vulnerable to shortages and contributing to illegal transactions and circulation of substandard and falsified medicines, such as in the African region. However, as noted by the Nigerian interviewee, stakeholders in LMICs are often interested in exploring partnerships with biosimilar companies to secure local manufacturing and procurement agreements.

Low awareness of biosimilars

Different stakeholders may still be unaware of the use of biosimilars in some LMICs. Prescribers may lack the confidence to prescribe biosimilars, and patients might lack trust in biosimilars. The Colombian interviewee stressed that patients tend to think that biosimilars may have quality issues and noted that such negative perception is likely to originate from the HCPs, which ends up influencing patients. A survey among Nigerian pharmacists published in 2022 suggests a lack of knowledge of biosimilars, as most pharmacists incorrectly responded that a biosimilar is structurally identical to its RP [48].

Lack of effective policies encouraging access to and use of biosimilars

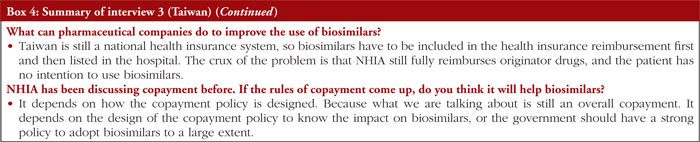

The lack of policies and guidance encouraging access to and use of biosimilars may also contribute to sub-optimal biosimilar use. The Taiwanese interviewee noted a need for a clear policy to encourage hospitals to adopt biosimilars into their formularies. According to the interviewee, hospitals still prefer to use the RPs as not much educational awareness and/or effective incentives are given to use biosimilars.

To summarize, better access to biosimilars in LMICs is not only a matter of availability but also education, training, capability building, capacity management, better distribution infrastructure, and distribution systems. The LMIC drug regulators should focus on reducing counterfeit or low-quality biosimilars, black-marketing, unethical marketing, product manipulation, and corruption at various levels [49].

Boxes 2, 3 and 4 present a summarized version of the interviews held with former government officials or people affiliated with governments and familiar with the reimbursement of biosimilars in Nigeria, Colombia, and Taiwan.

Policy recommendations

Policy recommendations for accessing and using quality-assured biosimilars in LMICs are outlined below. These recommendations should be considered as general guidance and not as ‘one-size-fits-all’ policies. Not all recommendations may be relevant to all LMICs, and these should always be tailored to the local contexts and economies in different countries.

Strengthening regulatory systems

Regulatory requirements for biosimilar licensing in LMICs should be strengthened to facilitate approval of safe and quality-assured biosimilars. Following examples from WHO and stringent regulatory authorities, i.e. the US FDA and EMA, can help LMICs in this engagement. In Africa, establishing the African Medicines Agency (AMA) could help pool regulatory resources among countries, facilitate access to quality-assured medicines, and help fight counterfeit medicines [46, 50]. As of October 2023, 27 African countries had ratified the AMA treaty, and other countries had signed and were expected to ratify it [51]. Finally, while it is key for regulatory pathways to be stringent enough to ensure only effective, safe, and high-quality biosimilars can enter the market, streamlining requirements when there is sound evidence to do so can contribute to accelerating biosimilars’ development.

Strengthening pharmacovigilance

Pharmacovigilance systems should be strengthened to monitor, and report suspected reactions or adverse events appropriately. Given biosimilars’ complexity, pharmacovigilance is important to evaluate their long-term safety [52].

Providing guidance for prescribing biosimilars and increasing education on biosimilars

Providing clear guidelines for prescribing biosimilars can help to increase prescribers’ confidence in prescribing biosimilars. Additionally, increasing patient education on biosimilars, especially in countries where these may be linked to low levels of trust, can mitigate possible nocebo effects, wherein the symptoms or adverse events are mainly due to patients’ negative perceptions about the product rather than its mechanism of action, efficacy or safety [53]. As highlighted by the Nigerian interviewee, initiatives from multiple stakeholders (including members of government, non-governmental organizations, healthcare professionals, and the media) can educate the patients on key topics such as counterfeit biosimilars (and how to potentially recognize them) and the importance of following treatment guidance from trusted sources.

Strengthening national policies to increase access and adoption of biosimilars

Depending on the local context, national policies should be implemented to support increased access to and adoption of biosimilars. Relevant national policies could include promoting higher reimbursement levels for biosimilars and providing incentives to prescribe biosimilars, as narrated by the Taiwanese interviewee.

Encouraging local manufacturing

Encouraging local manufacturing can facilitate stable supply and availability, and consequent access, to biosimilars in the LMICs. Global companies may increase their manufacturing presence in LMICs or may improve the manufacturing capabilities of other local manufacturers via technology transfers, which could be part of licensing agreements. Ideally, promoting local manufacturing should be part of a wider plan to improve business conditions in certain LMICs.

Encouraging stakeholders’ initiatives promoting access to biosimilars

At both local and global levels, various initiatives led by different stakeholders can improve access to biosimilars in the LMICs. Company-led initiatives can involve partnerships with local authorities, patient support programmes, and free access to patients. Initiatives led by international organizations such as the WHO PQP can support countries to acquire quality-assured biosimilars.

Potential selection criteria for quality-assured biosimilars

Following a biosimilar’s regulatory approval, public and private payers make purchasing decisions to choose amongst potential biosimilars. Acknowledging that a biosimilar’s price and affordability requirements remain key factors for payers in LMICs, there are additional criteria beyond price to help stakeholders choose quality-assured biosimilars.

Product characterization and quality

The manufacturing process of each biotechnological medicinal product undergoes several changes during its life cycle, which may have a substantial impact on the product. Therefore, the new and previous versions should be deemed to be comparable by appropriate tests, usually physicochemical, structural, and in vitro functional tests [54]. The demonstration of comparability does not have to mean that the pre-change and post-change products are identical but that they are highly similar, and that the existing knowledge is sufficient to conclude that the observed differences have no adverse impact on the safety or efficacy of the medicinal product [18]. The advancement in protein structure characterization and other processes has led to many improvements in the manufacturing and product testing that a biosimilar manufacturer can measure up to 100 critical quality attributes (CQAs) across 40 or more biochemical, analytical, pharmacological, or functional assays to ensure bio-similarity [29]. The national control laboratories at LMICs should ensure that adequate tests are carried out to check that the biosimilar products comply with WHO specifications to provide assurance to prescribers, payors, and patients on the product’s quality prior to release in the market [20].

Regulatory approval in developed countries

A biosimilar’s regulatory approval by a regulatory authority that is a part of the International Council for Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for Human Use (ICH), such as the US FDA, EMA, and the Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency (PMDA) of Japan, could increase LMICs stakeholders’ confidence in the quality of a biosimilar. Additionally, the WHO PQP allows LMICs to adopt pre-qualified biosimilars with confidence.

Adverse events

In addition to considering the adverse events that emerge from the clinical trials, pharmacovigilance data and results from post-marketing studies can provide additional useful information on the safety of a biosimilar.

Availability of real-world evidence (RWE)

RWE, even from the HICs, can further reassure payers about a product’s safety, efficacy, and quality. The RWE can provide information on the use of a biosimilar in populations not included in clinical trials, such as diverse ethnic groups, and potentially information on the biosimilar’s use in other indications (not explored as part of the original clinical trials).

Product packaging

Clear packaging and barcoding on the product’s per-dose packaging can help limit medication errors [55] and potentially help distinguish between quality-assured biosimilars and fake or counterfeit biosimilars.

Related devices/delivery mechanisms

The possibility of administering the biosimilar via patient-friendly devices or delivery mechanisms (for instance, insulin pens) can be valuable and improve HCPs’ and patients’ experience.

Capability, capacity, and presence of the manufacturer

The manufacturer’s capability, capacity, and geographical presence can impact the availability of a biosimilar. Payers could consider the following characteristics of the manufacturer: experience and reputation with biosimilars; records related to products’ quality; supply conditions such as the number of manufacturing centres; manufacturing location; supply chain resilience; positive history related to shortages and recalls; capability to maintain adequate production; and counterfeit protection [56, 57].

Additional services offered by the manufacturer

Additional offerings, such as educational materials, can be helpful during treatment initiation and continuation for HCPs and patients.

Conclusion

Biosimilars are more affordable treatment options than their RPs and can help increase access to medicines in LMICs and HICs. Experiences from the HICs confirm several benefits of biosimilars. Biosimilar companies actively market their products in LMICs, creating opportunities to expand treatment options, particularly needed for under-served and under- or un-insured communities. As governments and other stakeholders increasingly recognize the potential of biosimilars in addressing accessibility and affordability challenges, more biosimilars are likely to enter the global market. Increased access to biosimilars can benefit health systems and economies by increasing competition and reducing the prices of expensive biologics. Despite establishing regulatory pathways for biosimilars in LMICs, focused approaches are required to strengthen the regulatory requirements further and facilitate access to quality-assured biosimilars. Additional challenges related to adopting quality-assured biosimilars persist across LMICs and may include dependence on importation, low awareness of biosimilars, and lack of effective policies encouraging their access and use. Recognizing that affordability remains a critical factor when making decisions around procuring biosimilars, stakeholders in LMICs can consider some characteristics of the product and the manufacturer to ensure the selection of quality-assured biosimilars. Proposed policy recommendations to promote access to biosimilars in this review article include strengthening regulatory systems and pharmacovigilance, providing guidelines for prescribing biosimilars, increasing education on biosimilars, strengthening national policies to increase access to and adoption of biosimilars, encouraging local manufacturing, and encouraging stakeholders’ initiatives promoting access to biosimilars.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge Clarivate for supporting the research work and drafting various versions of the review article.

Funding sources

Biocon Biologics Limited funded this paper.

Author contributions

Biocon Biologics Limited (BBL) defined the study methodology and commissioned the research work and development of a first draft of the review article to Clarivate. The authors provided guidance and strategic advice during the development and finalization of the review article. All authors contributed to, reviewed, and approved the review article to be published.

Data availability statement

The data supporting the research findings are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Competing interests: PP, RK, GKR, SU, and SNA are Biocon Biologics Limited (BBL) employees and are eligible for stocks and stock options. NS and MEE are employees of Biocon Biologics Inc. USA. SM is engaged as a consultant with BBL. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Authors

Pritha Paul1, PhD

Rahul Kapur2,*, MBBS, PhD

Shivani Mittra2, MPharm, PhD

Nimish Shah3, JD, MBA

Gopal K Rao1, MSc

Matthew E Erick4, BS, RPh

Susheel Umesh1, BPharm, MBA

Sandeep N Athalye2, MBBS, MD

1Market Access (Emerging Markets), Biocon Biologics Ltd, Bengaluru, India

2Clinical Development and Medical Affairs, Biocon Biologics Ltd, Bengaluru, India

3Policy and Advocacy (North America), Biocon Biologics Inc, USA

4Market Access (Advanced Markets), Biocon Biologics Inc, USA

Biocon Biologics Ltd

Biocon House, Tower 3, Semicon Park, Plot No 29-P1 & 31-P, KIADB Industrial Area, Electronic City Phase – 2, Hosur Road, Bengaluru 560100, Karnataka, India

References

1. Malekzadeh A, Michels K, Wolfman C, Anand N, Sturke R. Strengthening research capacity in LMICs to address the global NCD burden. Glob Health Action. 2020;13(1):1846904.

2. Morin S, Segafredo G, Piccolis M, Das A, Das M, Loffredi N, et al. Expanding access to biotherapeutics in low-income and middle-income countries through public health non-exclusive voluntary intellectual property licensing: considerations, requirements, and opportunities. Lancet Glob Health. 2023;11(1):e145-e154.

3. World Health Organization. Noncommunicable diseases. 11 September 2023. [homepage on the Internet]. [cited 2024 Apr 25]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/noncommunicable-diseases#:~:text=Noncommunicable%20diseases%20(NCDs)%20kill%2041,%2D%20and%20middle%2Dincome%20countries

4. World Health Organization. Global expenditure on health: public spending on the rise? Geneva: World Health Organization; 2021 [homepage on the Internet]. [cited 2024 Apr 25]. Available from: https://files.aho.afro.who.int/afahobckpcontainer/production/files/2_Global_expenditure_on_health_Public_spending_on_the_rise.pdf

5. World Health Organization. Web Annex A. World Health Organization Model List of Essential Medicines – 23rd List, 2023. In: The selection and use of essential medicines 2023: Executive summary of the report of the 24th WHO Expert Committee on the Selection and Use of Essential Medicines, 24 – 28 April 2023. Geneva: World Health Organization [homepage on the Internet]. [cited 2024 Apr 25] Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-MHP-HPS-EML-2023.02

6. Cardone C, Arnold D. The cancer treatment gap in lower- to middle-income countries. Oncology. 2023;101(Suppl 1):2-4.

7. The Center for Biologic Policy Evaluation. About biologics and biosimilars [homepage on the Internet]. [cited 2024 Apr 25]. Available from: https://biologicspolicy.com/about-biologics-biosimilars

8. World Health Organization. Guidelines on evaluation of biosimilars. 2022 [homepage on the Internet]. [cited 2024 Apr 25]. Available from: https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/biologicals/bs-documents-(ecbs)/annex-3—who-guidelines-on-evaluation-of-biosimilars_22-apr-2022.pdf

9. Poon SY, Hsu JC, Ko Y, SC C. Assessing knowledge and attitude of healthcare professionals on biosimilars: a national survey for pharmacists and physicians in Taiwan. Healthcare (Basel). 2021;9(11):1600.

10. GaBI Online – Generics and Biosimilars Initiative. Key facts of biosimilars approval regulation in Brazil [www.gabionline.net]. Mol, Belgium: Pro Pharma Communications International; [2024 Apr 25]. Available from: https://www.gabionline.net/biosimilars/general/key-facts-of-biosimilars-approval-regulation-in-brazil

11. Kang H-N, Thorpe R, Knezevic I, Baek D, Chirachanakul P, Chua HM, et al. Biosimilars – Status in July 2020 in 16 countries. Generics and Biosimilars Initiative Journal (GaBI Journal). 2021;10(1):4-32. doi.10.5639/gabij.2021.1001.002

12. GaBI Online – Generics and Biosimilars Initiative. Biocomparables approved in Mexico 2022. [www.gabionline.net]. Mol, Belgium: Pro Pharma Communications International; [cited 2024 Apr 25]. Available from: https://www.gabionline.net/biosimilars/general/biocomparables-approved-in-mexico

13. GaBI Online – Generics and Biosimilars Initiative. Biosimilares aprobados en Colombia. 2022. [www.gabionline.net]. Mol, Belgium: Pro Pharma Communications International; [cited 2024 Apr 25]. Available from: https://gabionline.net/es/biosimilares/general/biosimilares-aprobados-en-colombia

14. National Pharmaceutical Regulatory Agency (NPRA), Ministry of Health, Malaysia. Biosimilar approved. 23 February 2024 [homepage on the Internet]. [cited 2024 Apr 25]. Available from: https://www.npra.gov.my/index.php/en/informationen/new-products-indication/biosimilars-approved.html

15. Gherghescu I, Delgado-Charro M. The biosimilar landscape: an overview of regulatory approvals by the EMA and FDA. Pharmaceutics. 2021;13(1):48.

16. Pfizer. Biologics vs. biosimilars: understanding the difference. 2022 [homepage on the Internet]. [cited 2024 Apr 25]. Available from: https://www.pfizer.com/news/articles/biologics_vs_biosimilars_understanding_the_differences

17. Cazap E JI, McBride A, Popovian R, Sikora K. Global acceptance of biosimilars: importance of regulatory consistency, education, and trust. Oncologist. 2018;(10):1188-98.

18. Kang H-N, Thorpe R, Knezevic I. The regulatory landscape of biosimilars: WHO efforts and progress made from 2009 to 2019. Biologicals. 2020:65:1-9.

19. Kang H-N, Thorpe R, Knezevic I, Casas Levano M, Chilufa MB, Chirachanakul P, et al. Regulatory challenges with biosimilars: an update from 20 countries. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2021;1491(1):42-59.

20. World Health Organization. Guidelines on evaluation of biosimilars 2022 [homepage on the Internet]. [cited 2024 Apr 25]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/guidelines-on-evaluation-of-biosimilars

21. McKinsey & Company. What’s next for biosimilars in emerging markets? 2019. [cited 2024 Apr 25]. Available from: https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/life-sciences/our-insights/whats-next-for-biosimilars-in-emerging-markets

22. World Health Organization. Prequalification of medicines by WHO 2013 [homepage on the Internet]. [cited 2024 Apr 25]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/prequalification-of-medicines-by-who

23. Morin S, Segafredo G, Piccolis M, Das A, Das M, Loffredi N, et al. Expanding access to biotherapeutics in low-income and middle-income countries through public health non-exclusive voluntary intellectual property licensing: considerations, requirements, and opportunities. Lancet Glob Health. 2023;11(1):E145-E154.

24. Niazi SK. Biosimilars: harmonizing the approval guidelines. Biologics. 2022;2(3): 171-95.

25. Easey A. The UK moves into the fast lane for biosimilar regulatory approvals. 29/07/2022. [cited 2024 Apr 25]. Available from: https://www.penningtonslaw.com/news-publications/latest-news/2022/the-uk-moves-into-the-fast-lane- for-biosimilar-regulatory-approvals.

26. gov.br. Anvisa aprova consulta pública sobre medicamentos biossimilares 2023 [homepage on the Internet]. [2024 Apr 25]. Available from: https://www.gov.br/anvisa/pt-br/assuntos/noticias-anvisa/2023/anvisa-aprova- consulta-publica-sobre-medicamentos-biossimilares

27. Móxico Gd. Cofepris transforma la política regulatoria: agilidad en registro de medicamentos genéricos y biosimilares 2023 [homepage on the Internet]. [cited 2024 Apr 25]. Available from: https://www.gob.mx/cofepris/articulos/cofepris-transforma-la-politica-regulatoria-agilidad-en-registro-de-medicamentos-genericos-y-biosimilares?idiom=es

28. GaBI Online – Generics and Biosimilars Initiative. Biosimilar regulations perspective in Latin America to improve cancer treatment access [www.gabionline.net]. Mol, Belgium: Pro Pharma Communications International; [cited 2024 Apr 25]. Available from: https://www.gabionline.net/biosimilars/research/biosimilar-regulations-perspective-in-latin-america-to-improve-cancer-treatment-access.

29. Joshi, SR, Mittra S, Raj P, Suvarna VR, Athalye SN. Biosimilars and Interchangeable biosimilars: facts every prescriber, payor, and patient should know. Insulins perspective. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2023;23(8):693-704.

30. Sullivan MG. Biosimilar labeling guidance suggests cutting interchangeability details from labels. Regulatory Focus 2023. Available from: https://www.raps.org/news-and-articles/news-articles/2023/9/biosimilar-labeling- guidance-suggests-cutting-inte.

31. Barbier L, Vulto AG. Interchangeability of biosimilars: overcoming the final hurdles. Drugs. 2021;81(16):1897-903.

32. Kurki P, Van Aerts L, Wolff-Holz E, Giezen T, Skibeli V, Weise M. Interchangeability of biosimilars: a European perspective. BioDrugs. 2017;31:83–91.

33. Kurki P, Barry S, Bourges I, Tsantili P, Wolff-Holz E. Safety, immunogenicity and interchangeability of biosimilar monoclonal antibodies and fusion proteins: a regulatory perspective. Drugs. 2021:81:1881-96.

34. Troein P, Newton M, Scott K, Mulligan C. The impact of biosimilar competition in Europe. December 2021. [cited 2024 Apr 25]. Available from: https://www.iqvia.com/-/media/iqvia/pdfs/library/white-papers/the-impact-of-biosimilar-competition-in-europe-2021.pdf

35. Amgen. 2022 Biosimilar Trends Report. 2022 [homepage on the Internet]. [cited 2024 Apr 25]. Available from: https://www.amgenbiosimilars.com/commitment/2022-Biosimilar-Trends-Report#:~:text=Biosimilars%20Are%20Expanding%20Into%20New,than%2070%25%20since%20October%202015

36. Troein P, Newton M, Stoddart K, Arias A. The impact of biosimilar competition in Europe. 2022. [cited 2024 Apr 25]. Available from: https://www.iqvia.com/-/media/iqvia/pdfs/library/white-papers/the-impact-of-biosimilar-competition-in-europe-2022.pdf

37. Maxwell A. Biosimilars have lowered costs for Medicare Part B and enrollees, but opportunities for substantial spending reductions still exist. Department of Health and Human Services Office of Inspector General; September 2023 [cited 2024 Apr 25]. Available from: https://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/OEI-05-22-00140.pdf

38. Patel KB, Luiz AJL, Tang WY, Fung S. The role of biosimilars in value-based oncology care. Cancer Manag Res. 2018;10:4591-602.

39. IQVIA. Unlocking biosimilar potential. April 2023 [homepage on the Internet]. [cited 2024 Apr 25]. Available from: https://www.iqvia.com/-/media/iqvia/pdfs/institute-reports/unlocking-biosimilar-potential/iqi-unlocking-biosimilar-potential-04-23-forweb.pdf

40. Biocon Biologics Limited. Strategic action. Transformational growth. Integrated annual report FY 2023 [homepage on the Internet]. [cited 2024 Apr 25]. Available from: https://www.bioconbiologics.com/docs/Biocon_Biologics_Integrated_Annual_Report_2023.pdf

41. Debiasi M, Reinert T, Kaliks R, Amorim G, Caleffi M, Sampaio C, et al. Estimation of premature deaths from lack of access to anti-her2 therapy for advanced breast cancer in the Brazilian public health system. J Global Oncol. 2016;3(3).

42. Luo X, Du X, Li Z, Liu J, Lv X, Li H, et al. Clinical benefit, price, and uptake for cancer biosimilars vs reference drugs in China: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Network Open. 2023;6(10):e2337348.

43. MinSalud. ABC of biotech drugs. 2014 [homepage on the Internet]. [cited 2024 Apr 25]. Available from: https://www.minsalud.gov.co/sites/rid/Lists/BibliotecaDigital/RIDE/VS/MET/abc-biotech-drugs.pdf

44. México Gd. Biocomparables, opción para reducir costos en el Sistema Nacional de Salud. 2017 [homepage on the Internet]. [cited 2024 Apr 25]. [Available from: https://www.gob.mx/cofepris/articulos/biocomparables-opcion-para-reducir-costos-en-el-sistema-nacional-de-salud-136953

45. Chong SC, Rajah R, Chow PL, Tan HC, Chong CM, Khor KY, et al. Perspectives toward biosimilars among oncologists: a Malaysian survey. J Oncol Pharm Pract. 2022: 10781552221104773.

46. Ncube BM, Dube A, Ward K. Establishment of the African Medicines Agency: progress, challenges and regulatory readiness. J Pharm Policy Pract. 2021;14(1):29.

47. World Health Organization. 1 in 10 medical products in developing countries is substandard or falsified. 2017 [homepage on the Internet]. [cited 2024 Apr 25]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news/item/28-11-2017-1-in-10-medical-products-in-developing-countries-is-substandard-or-falsified

48. Okoro RN, Hedima EW, Aguiyi-Ikeanyi CN. Knowledge, attitudes, and practices of pharmacists toward biosimilar medicines in Nigeria. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2022;62(1):79-85.

49. Abraham I. Column: 1 billion people can access biosimilars; what about the other 7 billion? Am J Manag Care. 2022.

50. Sidibé M, Dieng A, Buse K. Advance the African Medicines Agency to benefit health and economic development. BMJ. 2023;380:386.

51. Likuyani, B. New country ratifies the African Medicines Agency Treaty 2023. [cited 2024 Apr 25]. Available from: https://africanpharmaceuticalreview.com/new-country-ratifies-african-medicines-agency-treaty/

52. Oza B, Radhakrishna S, Pipalava P, Jose V. Pharmacovigilance of biosimilars – why is it different from generics and innovator biologics? J Postgrad Med. 2019;65(4):227-32.

53. Colloca L, Panaccione R, Murphy TC. The clinical implications of nocebo effects for biosimilar therapy. Front Pharmacol. 2019;10:1372.

54. European Medicines Agency. ICH Q5E Biotechnological/biological products subject to changes in their manufacturing process: comparability of biotechnological/biological products – Scientific guideline [homepage on the Internet]. [cited 2024 Apr 25]. Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/ich-q5e-biotechnological-biological-products-subject-changes-their-manufacturing-process-comparability-biotechnological-biological-products-scientific-guideline

55. Barbier L, Vandenplas Y, Boone N, Huys I, Janknegt R, Vulto AG. How to select a best-value biological medicine? A practical model to support hospital pharmacists. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2022;79(22):2001-11.

56. Amgen. 2021 Biosimilar Trends Report. 2021 [homepage on the Internet]. [cited 2024 Apr 25]. Available from: https://www.amgenbiosimilars.com/-/media/Themes/Amgen/amgenbiosimilars-com/Amgenbiosimilars-com/pdf/USA-CBU-80961_Amgen-Biosimilars-Trend-Report.pdf

57. Smeeding J, Malone DC, Ramchandani M, Stolshek B, Green L, Schneider P. Biosimilars: considerations for payers. P T. 2019;44(2):54-63.

|

Author for correspondence: Rahul Kapur, MBBS, PhD, Biocon Biologics Ltd, Biocon House, Tower 3, Semicon Park, Plot No 29-P1 & 31-P, KIADB Industrial Area, Electronics City Phase II, Bangalore-560100, Karnataka, India |

Disclosure of Conflict of Interest Statement is available upon request.

Copyright © 2024 Pro Pharma Communications International

Permission granted to reproduce for personal and non-commercial use only. All other reproduction, copy or reprinting of all or part of any ‘Content’ found on this website is strictly prohibited without the prior consent of the publisher. Contact the publisher to obtain permission before redistributing.

4 Replies to “Increasing adoption of quality-assured biosimilars to address access challenges in low- and middle-income countries”