It is time to change US trade policy to foster access to medicines

Published on 2019/10/28

Generics and Biosimilars Initiative Journal (GaBI Journal). 2020;9(1):25-7.

|

Abstract: |

Submitted: 11 September 2019; Revised: 29 September 2019; Accepted: 4 October 2019; Published online first: 18 October 2019

Introduction

Trade agreements are no longer international deals to lower tariffs, increase competition and benefit consumers with lower prices. Today, they have become a tool for some interest groups to tilt the laws and regulations in their favour, at the expense of consumers. This is very much the case for intellectual property (IP) provisions related to pharmaceuticals.

An analysis of the United States International Trade Commission (USITC) about the likely effect of the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA) concluded that ‘[i]n the biopharmaceutical sector, estimated gains to originator firms from stronger protections are likely to be offset by losses to generics firms’. While high drug prices have become one of the biggest concerns for Americans, the United States Trade Representative (USTR) continues to negotiate trade agreements that benefit one side of the industry at the expense of the other and consumers alike.

The generics industry has played a critical role in increasing access to medicines in the US but gradually faces more challenges. More recently, additional monopoly rights granted to biologicals have been at the core of the debate over trade agreements such as the USMCA. Provisions related to biologicals in the USMCA may undermine the development of the biosimilar industry and with that, any hope for American patients’ access to much-needed drugs. The sustainability of the generic industry and the development of the biosimilar industry are literarily at risk in part because of US trade policy. The time has come for a shift to restore some balance to US trade policy.

Trade agreements: putting at risk the generics and biosimilars industry

The newly renegotiated North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) will have winners and losers among the various economic sectors. The pharmaceutical industry is a case in point. An analysis of the USITC about the likely effect of the USMCA concluded that ‘[i]n the biopharmaceutical sector, estimated gains to originator firms from stronger protections are likely to be offset by losses to generics firms’ [1].

In other words, on pharmaceutical issues US trade negotiators have picked a winner on one side of the industry, at the expense of the other. This is not what trade negotiators should be doing. On the contrary, they should be pursuing equal growth and export opportunities for all industry sectors.

I know because I used to be a trade negotiator. For years, the US has been the country preaching the importance of endorsing the principles of a free market economy, ending protectionist measures and fostering competition. Trade agreements sought to lower trade barriers such as tariffs to increase competition, which would lead to lower prices thus benefiting consumers. This was the rationale behind trade agreements. However, trade negotiations have changed and today they often reflect the interests of powerful lobbying groups that succeed in including provisions that put them at a comparative advantage vis-à-vis other industry sectors and consumers.

A few months ago, the New England Journal of Medicine published an article showing how several trade agreements have included increasingly higher levels of IP protection that restrict competition in the pharmaceutical market, which is critical to lower drug prices [2]. Unfortunately, US trade negotiators continue to engage in trade negotiations that side with the originator pharmaceutical industry, often called the brand industry, at the expense of the generic and biosimilar pharmaceutical industry and consumers.

This has been going on for too long, starting with the inclusion of the first IP rights chapter in a global trade agreement. I am referring to the Agreement on Trade Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS) of the Uruguay Round of General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) that was concluded in December 1994. Since the beginning of this negotiation in 1986, US trade negotiators have sought to benefit the brand-name industry at the expense of the generics industry and consumers in the US and worldwide.

Some may argue that following the adoption of the 1984 Hatch-Waxman Act the US generic industry was solely focused on growing domestically and, unaware of the potential impact of trade agreements, did not engage with the government in the definition of US trade policies related to pharmaceuticals. This left room for the USTR to adopt the positions supported by the brand-name industry, which turned into the ‘U.S. pharmaceutical industry position’. However, the generics industry and those of us working on access to medicines for many years have relentlessly tried to get trade negotiators to adjust US trade policy to strike a balance on IP matters related to pharmaceuticals that fosters both innovation and competition. This would support the growth of both brand and generic/biosimilar companies and therefore patients’ access to both new but also more affordable drugs.

In February 2007 I published what I hoped would be a provocative article to put in evidence that the Office of the USTR was taking sides, and therefore undermining timely access to more affordable safe and effective drugs. Indeed, the title of the article was ‘Trade agreements and public health: are US trade negotiators building an intellectual property platform against the generic industry? Are they raising the standards to go beyond the US law?’, [3].

In the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement: Likely Impact on the U.S. Economy and on Specific Industry Sectors, the International Trade Commission (ITC) concluded that ‘In the biopharmaceutical sector, estimated gains to originator firms from stronger protections are likely to be offset by losses to generics firms’, confirming that trade agreements such as the USMCA benefited one side of the industry at the expense of the other. Much damage has been done in the past 20 years or so. I have been working on these issues for 27 years and I can see how generic companies are morphing before our eyes to adjust to an increasingly tilted system that benefits brand companies at their expense.

If we do not want the generics industry to fully disappear, it is imperative to change trade policies to seek more balanced provisions that benefit both sides of the industry and foster both the development of new drugs and competition. However, if we continue adopting longer and broader monopolies through these trade agreements, we will be putting at risk the sustainability of the generic/biosimilar industry and with that, patients access to more affordable drugs and their hopes for a healthier life. Indeed, while savings from competition from the incipient biosimilar industry have yet to be realized [4] in 2018 alone 90% prescriptions filled in the US were dispensed as generics, accounting for overall 22% of overall drug spending, and generating savings that totalled US$293 billion [5].

Concerns over the direction of US trade policies are even direr today as in the USMCA the USTR is trying to define some of the rules that will impact the development of the biosimilar industry. Biological drugs are the most expensive in the market, many of them with six figure prices, per patient, per year. Many of today’s cancer drugs are biological drugs. In a speech during the release of the Biosimilars Action Plan, former FDA Commissioner Scott Gottlieb explained that while less than two per cent of Americans use biologicals, they represent 40 per cent of total spending on prescription drugs [6].

The economic pressures of these drugs will grow dramatically and the system is becoming increasingly unsustainable. It is only a matter of time until Medicare and Medicaid come to a point when they can no longer pay for these drugs or insurance companies are unable to cover them without raising premiums or increasing copayments thus putting at risk patients’ access to life-saving drugs. If there is no shift in US trade policy on IP rights related to pharmaceuticals, it will not matter whether new drugs are invented as most citizens will not be able to afford them.

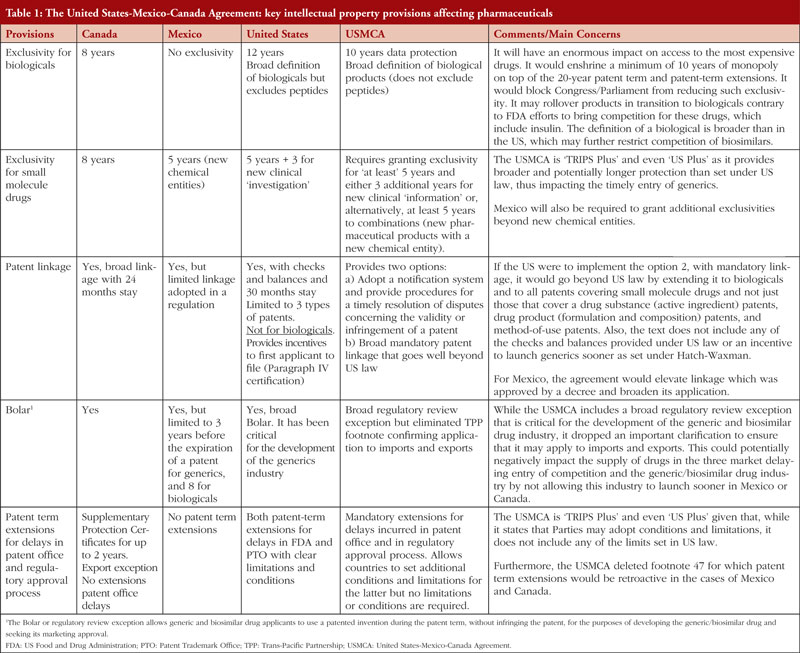

Table 1 lists some of the problematic IP provisions in the USMCA in terms of access to medicines, showing that there is no balance as it grants longer and broader monopolies to IP holders while failing to include provisions to ensure the expedited launch of generic and biosimilar drugs.

The USMCA includes a number of problematic provisions that will delay access to medicines not just for consumers in Canada and Mexico, but also in the US. Furthermore, it will negatively impact the US generics and biosimilars industry in the three markets. It is important to remember that the cost of developing a biosimilar drug may range between US$100 and US$250 million. As former FDA Commissioner Gottlieb stated, given the investments needed to develop biosimilars, creating efficient economies of scale for these drugs requires a global market [7]. Instead of opening new markets for these products, however, the USTR is seeking the adoption of standards, including in the USMCA, that create more barriers to entry thus putting at risk the development of this incipient and critical industry to ensure patients’ access to more affordable biological drugs.

In 2007, a handful of us worked with the House Ways and Means Committee in an effort to restore some balance in the IP provisions related to pharmaceuticals in the trade agreements the US had concluded with Colombia, Panama and Peru. The bipartisan New Trade Policy or May 10th Agreement, as it is now known, set a precedent for striking a better balance to promote both innovation and access. Two recent letters to Ambassador Lighthizer, one from most Democrats in the House Ways and Means Committee and the other from over 100 US Representatives, refer to the May 10th Agreement as a better agreement that should serve as a benchmark to modify some of the provisions of the USMCA. Fixing the USMCA will not solve the entire problem posed by high drug prices but will be a very important first step and may give a fighting chance to the development of the biosimilar industry that should play a critical role in lowering prices for life-saving biological drugs. It is time to change US trade policy on pharmaceuticals to reflect a better balance that protects patients and supports the growth of all industry sectors.

Competing interests: The author works for the generics industry.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; internally peer reviewed.

References

1. United States International Trade Union. U.S.-Mexico-Canada trade agreement: likely impact on the U.S. economy and on specific industry sectors. April 2019. Page 26 [homepage on the Internet]. [cited 2019 Sep 29]. Available from: https://www.usitc.gov/publications/332/pub4889.pdf

2. Bollyky T, Kesselheim AS. Pharmaceutical protections in U.S. Trade deals – what do Americans get in return? N Engl J Med. 2019;380(21):1993-5.

3. Jorge MF. Trade agreements and public health: are US trade negotiators building an intellectual property platform against the generic industry? Are they raising the standards to go beyond the US law? J Generic Med. 2007;4(3):169-79.

4. Mulcahy AW, Hlávka JP, Case SR. Biosimilar cost savings in the United States. Initial experience and future potential. Rand Health Q. 2018;7(4):3. eCollection 2018 Mar.

5. Association for Accessible Medicines. 2019 Generic drug and biosimilars access and savings in the U.S [homepage on the Internet]. [cited 2019 Sep 29]. Available from: https://accessiblemeds.org/resources/blog/2019-genericdrug-and-biosimilars-access-savings-us-report

6. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Remarks from FDA Commissioner Scott Gottlieb M.D., as prepared for delivery at the Brookings Institution on the release of the FDA’s Biosimilars Action Plan. 18 July 2018 [homepage on the Internet]. [cited 2019 Sep 29]. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/remarks-fda-commissioner-scott-gottlieb-md-prepared-delivery-brookings-institution-release-fdas

7. FDA Commissioner Scott Gottlieb, M.D. Capturing the benefits of competition for patients. America’s Health Insurance Plans (AHIP) National Health Policy Conference; 7 March 2018.

|

Author: Maria Fabiana Jorge, MBA, Founder and President, MFJ International, LLC, 1032 29th Street, NW, Washington, DC 20007, USA |

Disclosure of Conflict of Interest Statement is available upon request.

Copyright © 2020 Pro Pharma Communications International

Permission granted to reproduce for personal and non-commercial use only. All other reproduction, copy or reprinting of all or part of any ‘Content’ found on this website is strictly prohibited without the prior consent of the publisher. Contact the publisher to obtain permission before redistributing.