Naming and labelling of biologicals – a survey of US physicians’ perspectives

Published on 2016/12/14

Generics and Biosimilars Initiative Journal (GaBI Journal). 2017;6(1):7-12.

|

Introduction: The US Food and Drug Association (FDA) released its requirements for the non-proprietary naming of biological products in January 2017. Before the FDA’s release, the Alliance for Safe Biologic Medicines (ASBM) asked physicians for their views on the labelling and naming of biosimilar medicines. |

Submitted: 9 January 2017; Revised: 12 February 2017; Accepted: 13 February 2017; Published online first: 27 February 2017

Introduction

Biological medicines are therapeutic proteins produced using living cells. A copy of an original biological made by a different manufacturer is referred to as a biosimilar or follow-on biological rather than a generic drug because it will be similar, not identical, to the product it copies. Biosimilars are also referred to as subsequent entry biologics (SEBs) in Canada. As a result of the abbreviated biosimilar approval pathway [1], biosimilar medicines are now available in the US market.

The market uptake of biosimilars in the US will depend on regulatory policies [2], for which an agreed naming and labelling system will be key. A survey of the views of European physicians on familiarity of biosimilar medicines has demonstrated the need for distinguishable non-proprietary names to be given to all biologicals [3]. There have been calls for clear regulation in this area from Latin America [4], Malaysia [5] and beyond.

Since FDA has only distributed draft guidance on the naming of biosimilar medicines [6] at time of the survey, feedback from the physicians who prescribe biologicals may well be helpful in determining how these drugs are to be regulated. The Alliance for Safe Biologic Medicines (ASBM) invited 5,423 physicians in the US to complete a study on the naming of biologicals. A total of 433 physicians responded, of which 400 prescribers of biologicals qualified and completed the study. Prescribers were asked for their feedback on the non-proprietary biologicals naming proposal issued by FDA in August 2015 [6].

FDA has proposed a new policy that would require every biological – whether originator or biosimilar – to have a distinct non-proprietary scientific name. Prescribers concluded that FDA was right to require a distinct non-proprietary scientific name for every biological product – originator or biosimilar – that FDA had approved.

Product labelling is seen at the heart of building user confidence in biosimilars [7]. In a subsequent study, the ASBM invited 9,813 prescribers to complete a study on the labelling of biologicals. 624 of these responded, of which 400 qualified and completed the study. Physicians who completed the study were asked what information they would like to see in a biological product label in order to choose between multiple biosimilars and their reference products. Physicians were asked what information could be included in a label, such as what clinical data should be present; whether or not the product was a biosimilar; and whether or not it was interchangeable.

All the information included in the labelling survey was considered important by the physicians surveyed. The greatest importance was accorded to an indication that the drug was a biosimilar. Physicians responded that including information on interchangeability was slightly less important than this.

Sample characteristics and methodology

Physician biosimilars labelling survey

Four hundred physicians were recruited in the US to complete a 15-minute web-based questionnaire on biosimilar labelling. In a separate, independent study, 400 prescribers were recruited in the US to complete a 15-minute web-based questionnaire on biosimilar naming. Participants in both surveys received a standard cash stipend of US$25 for their time to complete the survey.

All participants in the labelling survey were located in the US. They were recruited from a large, reputable panel of physicians and were all board certified in one of the following six specialities: dermatology, endocrinology, nephrology, neurology, oncology, or rheumatology. All participants prescribed biological medicine.

Of the 400 physicians who completed the labelling survey, 23% specialized in dermatology, 15% in endocrinology, 16% in nephrology, 15% in neurology, 16% in oncology, and 16% in rheumatology.

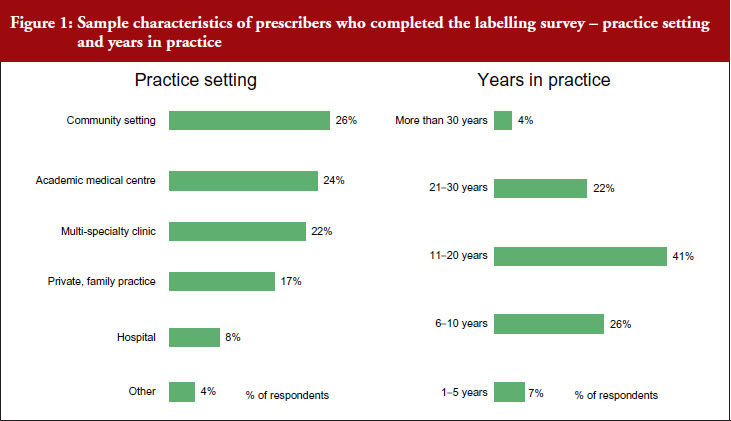

Prescribers completing the labelling survey worked in different settings. Twenty-six per cent of respondents worked in a community setting, 24% worked in an academic medical centre, 22% worked in a multi-speciality clinic, 17% worked in a private or family practice, 8% worked in a hospital, see Figure 1.

A total of 7% of participants in the labelling survey had spent 1–5 years in practice, 26% had spent 6–10 years, 41% had spent 11–20 years, 22% had spent 21–30 years, and 4% had spent more than 30 years in practice.

Sample characteristics and methodology

Physician biosimilars naming survey

The 400 participants in the naming survey were also based in the US. They were recruited from a large, global panel of healthcare professionals. Participants specialized in one of the following seven therapeutic specialities: dermatology, endocrinology, gastrointestinal, nephrology, neurology, oncology or rheumatology.

Among physicians completing the naming survey, 13% specialized in dermatology, 15% in endocrinology, 14% in gastrointestinal, 14% in nephrology, 14% in neurology, 16% in oncology, and 14% in rheumatology.

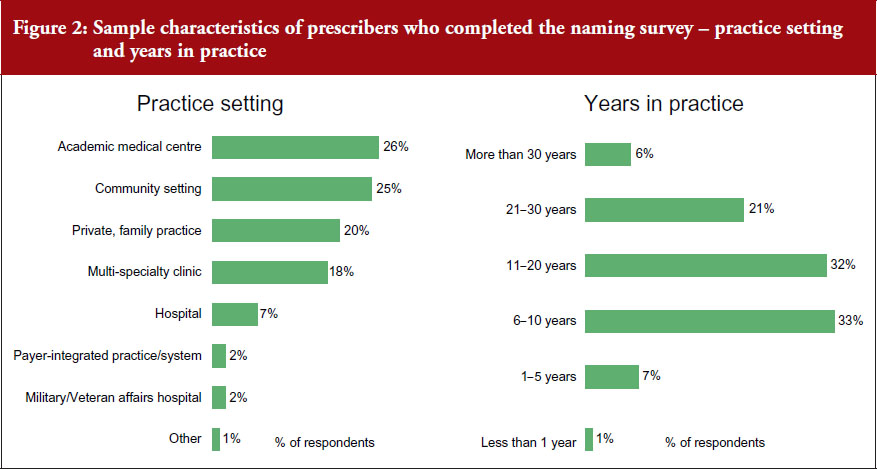

Prescribers completing the naming survey worked in different settings. 26% of respondents worked in an academic medical centre, 25% in a community setting, 20% in a private or family practice, 18% in a multi-specialist clinic, 7% in a hospital, and 2% in a military/veterans affairs hospital, see Figure 2.

A total of 7% of the physicians completing the naming survey had spent 1–5 years in practice, 33% had spent 6–10 years in practice, 32% had spent 11–20 years, 21% had spent 21–30 years, and 6% had spent more than 30 years in practice.

Participants in the naming survey were asked about their familiarity with FDA’s ‘Orange Book’ [8], the resource for Approved Drug Products with Therapeutic Equivalence Evaluations. The ‘Orange Book’ is a reference that identifies drug products approved on the basis of safety and effectiveness by FDA. Only 13% considered themselves very familiar with the book, 33% somewhat familiar, 26% vaguely familiar, and over a quarter (28%) had never heard of it. Only 4% used the Orange Book on a daily basis, 17% used it weekly, 14% used it monthly, 28% used it rarely, and 37% never used it.

Asked about their familiarity with FDA’s ‘Purple Book’ [9], that is, the resources for Lists of Licensed Biological Products with Reference Product Exclusivity and Biosimilarity or Interchangeability Evaluations, 8% were very familiar, 23% were somewhat familiar, 28% were vaguely familiar, and 41% had never heard of it. Only 4% used the Purple Book daily, 11% used it weekly, 12% used it monthly, 23% used it rarely, and over half (51%) never used it. Information contained in the Purple Book is designed to help enable a user to see whether a particular biological product has been determined by FDA to be biosimilar to or interchangeable with a reference biological product.

All physicians questioned in the naming survey claimed that they identified all medicines that they prescribed (biological and chemical) in the medical record.

Asked how they identified a medicine in the patient record, 25% said by scientific name, 34% by brand name, and 39% said it varied by medicine. Asked whether they would report an adverse event by using a drug’s product name or National Drug Code (NDC) number, 47% said they would use the brand name, 38% said they would use the scientific name, 2% would use the NDC number, and 13% had no preference.

Participants in the naming survey were asked for their attitudes and beliefs on product naming for originator and biosimilar products. 72% of respondents thought that if medicines had the same non-proprietary scientific name then they were probably structurally identical, 16% thought they would not be structurally identical, and 12% had no opinion. If two products have the same non-proprietary scientific name then 68% of respondents thought that a patient could safely receive either product and expect the same result. Twenty-one per cent of respondents would not expect the same result, and 11% had no opinion.

Asked about switching (when a patient is switched from one medicine to another), 60% of respondents thought that patients could safely be switched between two medicines that had the same non-proprietary scientific name and expect the same results. A quarter of respondents (25%) thought that patients could not safely be switched between two medicines with the same non-proprietary scientific name, 14% of respondents had no opinion.

Results

Physician responses to biosimilar labelling survey

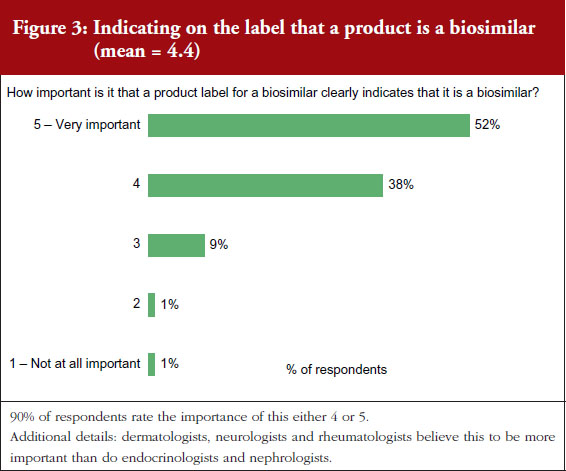

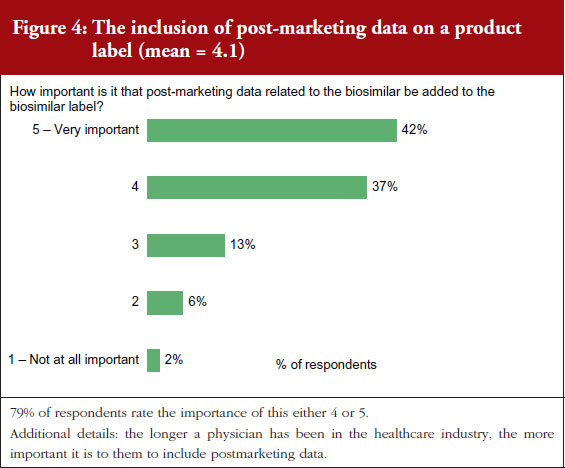

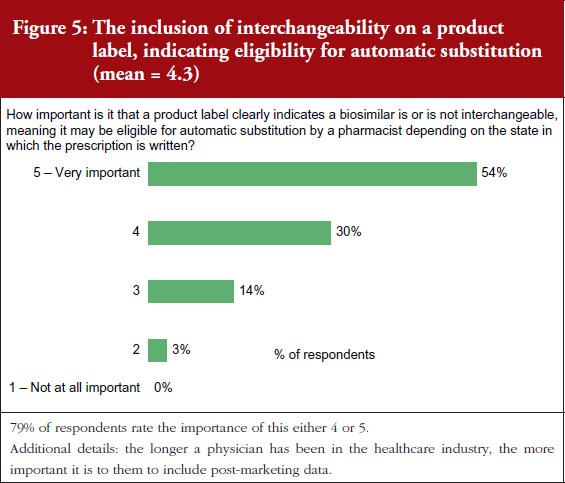

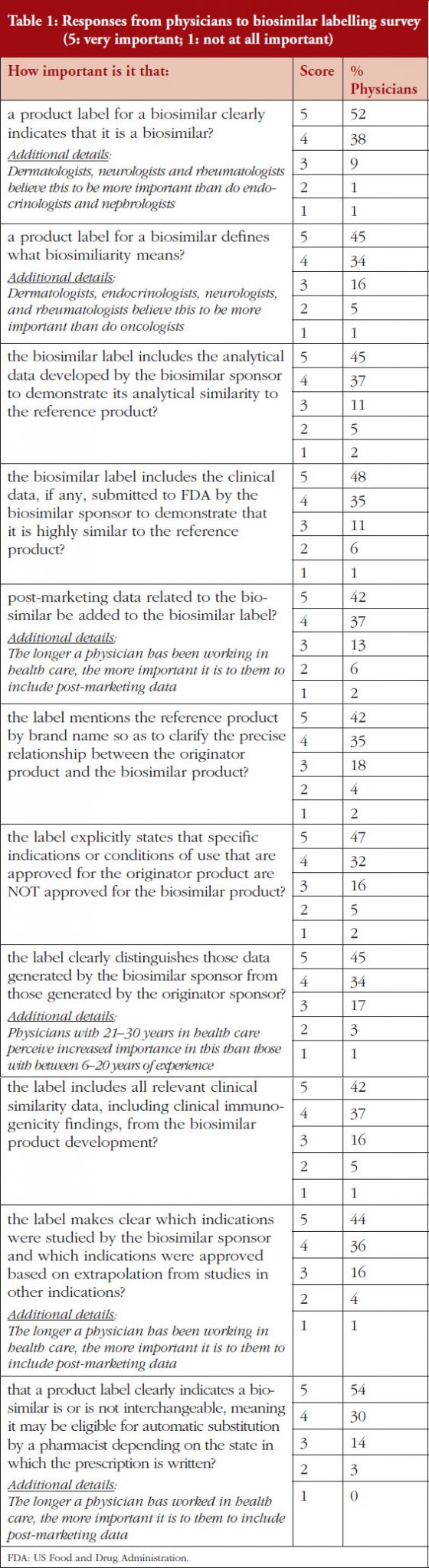

On a scale of 1–5, where 1 is not important at all and 5 is very important, 90% of the physicians questioned rated the importance of whether a product label for a biosimilar should clearly indicate that it is a biosimilar as either a 4 or 5, see Figure 3. On the question of post-marketing data, 79% of respondents rated the importance of including this data on the biosimilar label as either a 4 or 5, see Figure 4. On the question of interchangeability, 79% of respondents rated the importance of including whether or not a biosimilar is interchangeable as either a 4 or 5, see Figure 5. The responses of physicians to questions on biosimilar labelling are shown in Table 1.

Physician responses to biosimilar naming survey

In the naming survey, prescribers were asked whether FDA should require a distinct non-proprietary scientific name for every biological product FDA had approved – whether originator or biosimilar. FDA has recently proposed a distinct non-proprietary scientific name for all products, whether originator or biosimilar. This is intended to aid the process of pharmacovigilance and accurate prescribing and dispensing of medicines.

Respondents were asked for their views on the information that should be included in a product name and for their attitudes and beliefs on substitution.

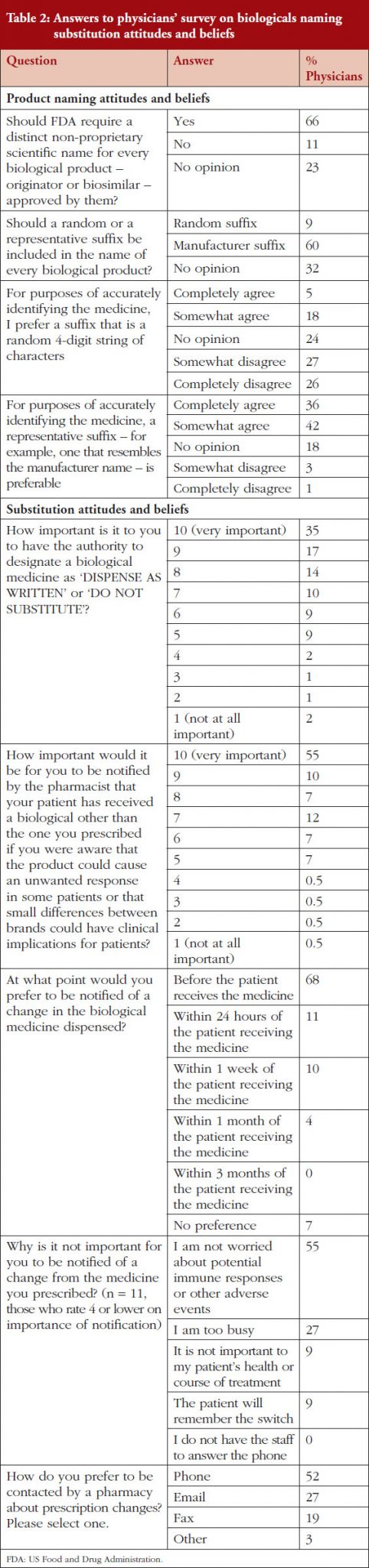

Responses to questions in the physicians’ naming survey are shown in Table 2.

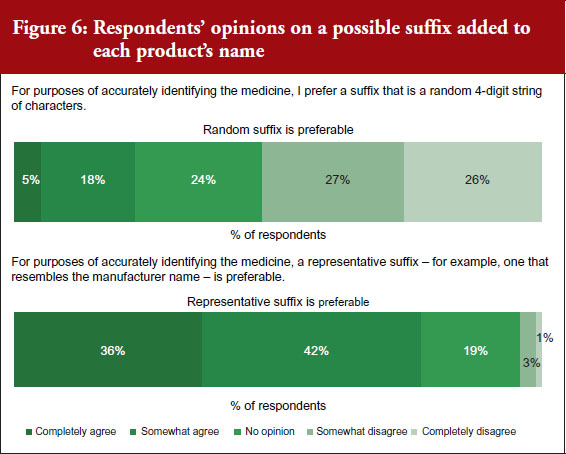

The spread of prescribers’ responses to questions related to the information contained in the representative suffix are given in Figure 6.

Conclusion

Generally speaking, all issues raised in the labelling survey were considered by the physicians surveyed to be very important for label inclusion. The inclusion of an indication of interchangeability was considered very important by 54% of the physicians. In fact, the physicians concluded that interchangeability was – of all the features included in the survey questions – the least important feature, with an average score of 4.1 out of 5. On average, the physicians gave the highest score, 4.4, to indicating that the drug was a biosimilar.

Segment differences were examined for all issues included in the survey. Segments among physicians included specialty, time spent working in health care, and practice setting. Very few specialty differences were noted and no differences for practice setting were noted. In general, the longer a physician had been in practice, the more important they thought it was to include the features mentioned in the survey on the biosimilar product label.

FDA proposal for a random suffix on a product’s name that does not indicate the manufacturer was not broadly welcomed, with only 9% of respondents agreeing with FDA. Instead, most physicians (60%) would prefer a suffix on the non-proprietary scientific name that is indicative of the product’s manufacturer. A third of respondents (32%) had no opinion.

In the naming survey, it was clear that respondents were not in complete agreement on how biological medicines, whether originators or biosimilars, are named. Reaching an agreement on the naming of these medicines will be key in building user confidence in biosimilars. The data presented here provide important feedback from a wide range of physicians who prescribe biologicals in the US. The findings will be helpful in determining how these biosimilar medicines are regulated in future.

|

Key points of the 2015 physicians naming and labelling survey

|

Funding sources

The Alliance for Safe Biologic Medicines (ASBM) is an organization composed of diverse healthcare groups and individuals – from patients to physicians, innovative medical biotechnology companies and others – who are working together to ensure patient safety is at the forefront of the biosimilars policy discussion. The activities of ASBM are funded by its member partners who contribute to ASBM’s activities. Visit www.SafeBiologics.org for more information.

Competing interests: Harry L Gewanter, MD, FAAP, FACR, Chairman of the Alliance for Safe Biologic Medicines (ASBM), and Mr Michael S Reilly, Esq, Executive Director; are employed by ASBM.

This paper is funded by ASBM.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Authors

Harry L Gewanter, MD, FAAP, FACR, Chairman

Michael S Reilly, Esq, Executive Director

Alliance for Safe Biologic Medicines, PO Box 3691, Arlington, VA 22203, USA

References

1. Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act of 2009, Public Law 111-148, Sec. 7001–7003, 124 Stat. 119. Mar. 23, 2010.

2. Cohen JP, Felix AE, Riggs K, Gupta A. Barriers to market uptake of biosimilars in the US. Generics and Biosimilars Initiative Journal (GaBI Journal). 2014;3(3):108-15. doi:10.5639/gabij.2014.0303.028

3. O Dolinar R, Reilly MS. Biosimilars naming, label transparency and authority of choice – survey findings among European physicians. Generics and Biosimilars Initiative Journal (GaBI Journal). 2014;3(2):58-62. doi:10.5639/gabij.2014.0302.018

4. Feijó Azevedo V, Mysler E, Aceituno Álvarez A, Hughes J, Javier Flores-Murrieta F, Ruiz de Castilla EM. Recommendations for the regulation of biosimilars and their implementation in Latin America. Generics and Biosimilars Initiative Journal (GaBI Journal). 2014;3(3):143-8. doi:10.5639/gabij.2014.0303.032

5. Abas A, Siew Khoon Khoo Y. Regulation of biologicals in Malaysia. Generics and Biosimilars Initiative Journal (GaBI Journal). 2014;3(4):193-8. doi:10.5639/gabij.2014.0304.044

6. GaBI Online – Generics and Biosimilars Initiative. FDA issues draft guidance on biosimilars labelling [www.gabionline.net]. Mol, Belgium: Pro Pharma Communications International; [cited 2017 Feb 12]. Available from: www.gabionline.net/Guidelines/FDA-issues-draft-guidance-on-biosimilars-labelling

7. European Biopharmaceutical Enterprises. Tell me the whole story: the role of product labelling in building user confidence in biosimilars in Europe. Generics and Biosimilars Initiative Journal (GaBI Journal). 2014;3(4):188-92. doi:10.5639/gabij.2014.0304.043

8. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Orange Book: approved drug products with therapeutic equivalence evaluations [homepage on the Internet]. [cited 2017 Feb 12]. Available from: http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/ob/default.cfm

9. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Purple Book: lists of licensed biological products with reference product exclusivity and biosimilarity or interchangeability evaluations [homepage on the Internet]. [cited 2017 Feb 12]. Available from: http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DevelopmentApprovalProcess/HowDrugsareDevelopedandApproved/ApprovalApplications/TherapeuticBiologicApplications/Biosimilars/ucm411418.htm

|

Author for correspondence: Michael S Reilly, Esq, Executive Director, Alliance for Safe Biologic Medicines, PO Box 3691, Arlington, VA 22203, USA |

Disclosure of Conflict of Interest Statement is available upon request.

Copyright © 2017 Pro Pharma Communications International

Permission granted to reproduce for personal and non-commercial use only. All other reproduction, copy or reprinting of all or part of any ‘Content’ found on this website is strictly prohibited without the prior consent of the publisher. Contact the publisher to obtain permission before redistributing.