Perceptions of physicians from private medical centres in Malaysia about generic medicine usage: a qualitative study

Published on 2014/03/24

Generics and Biosimilars Initiative Journal (GaBI Journal). 2014;3(2):63-70.

|

Introduction: The healthcare sector is one of the most rapidly expanding and dynamic industries in the world. Pharmaceutical expenditure is now growing faster than other components of healthcare overheads. Globally, pressures to manage pharmaceutical spending have led to increased prescribing of generic drugs. Use of generic drugs in private medical centres in Malaysia, however, remains low, despite intervention from the Ministry of Health. |

Submitted: 11 March 2014; Revised: 15 May 2014; Accepted: 19 May 2014; Published online first: 2 June 2014

Introduction

The healthcare sector is one of the most rapidly expanding and dynamic industries in the world. Pharmaceutical expenditure is now growing faster than other components of healthcare overheads [1, 2]. In many developed countries, comprehensive insurance coverage has increased healthcare expenditure by up to 60% because people benefit most from their insurance plans. In low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), pharmaceutical expenditure ranges from 20–60% of total healthcare spend because patented medicines are considerably more costly (as much as 10 times the cost) than their generics counterparts. Overall, insurance coverage in LMICs remains poor and many schemes do not cover expenses on medicines. Hence, medicines are still mainly purchased through out-of-pocket (OOP) payments in the private sector [3–5]. Globally, pressures to manage pharmaceutical spending have led to increased prescribing of generic drugs [6]. The World Health Organization (WHO) has reported that savings ranging between 9% and 89% could be made on individual medicines in the private sector if originator brands were substituted with the lowest priced generics equivalents [4, 7, 8].

In 2013, Malaysia’s expenditure on health care was estimated to be around US$12.1 billion. At 3.8% of its gross domestic product, Malaysia is spending little less on health care than its regional peers, but it does give an indication of the government’s commitment to healthcare provision. In tandem, Malaysia’s healthcare expenditure is estimated to be nearly US$20.4 billion by 2018 [9]. Malaysia has a two-tier healthcare provision, involving private services (about 30%) and public services (about 70%). In the civil sector, the Ministry of Health is the main government body accountable for the provision of healthcare services in the country. In public hospitals, patients pay a nominal amount for the treatment, whereas the cost of private health care is incurred fully by patients themselves, their employers, insurance companies, or both. Above all, the price of medicines in Malaysia’s private sector is determined by market forces, without any government intervention. A national drug pricing policy does not exist in Malaysia [10, 11].

As a result of spiralling healthcare costs, the practice of generics substitution is strongly supported by Malaysian health authorities under programmes such as ‘The Nationwide Road Show on Generic Medicines Awareness’, and the nationwide policy of substituting originator or patented drugs with generic drugs at government hospitals. The Ministry of Health is determined to promote the use of generic drugs, yet they have a mammoth task ahead. Studies conducted in the Malaysian market show that consumers can save up to 90% of the cost of treatment just by switching to generic drug products [10, 12]. In addition to reducing healthcare costs, the benefits of generic medications include increased adherence to treatment regimens [13, 14].

Malaysia’s Economic Transformation Plan launched in 2010 designated health care as one of 12 National Key Economic Areas to grow its economy. The aim is to achieve a 22% gross national income growth rate that will deliver US$5.5 billion gross national income by 2020. This will be driven by higher exports of generic medicines, enhanced generics, and increased clinical research in Malaysia [15]. Different studies conducted in Malaysia have revealed that patients and general physicians are concerned about the quality and efficacy of generics and that most do not prefer to use them [16, 17]. These concerns are somewhat valid, as the requirement for bioequivalence studies for all generic drugs was only implemented by the Ministry of Health in 2012. The introduction of bioequivalence requirement had started in 1999 and it was implemented in several phases until it was made mandatory in 2012. Therefore, some products on the market still need to undergo a bioequivalence study. Many generic drugs approved before this ruling were based on dissolution testing requirements. Most active ingredients and generic medicines are imported from other countries, and good manufacturing practices (GMP) audits are not conducted by the Ministry of Health for these foreign manufacturers. A recent study involving manufacturers of generic drug products in Malaysia has revealed that the level of generic drug prescribing, generics education, information available to healthcare professionals, and generics public awareness, are unsatisfactory [18].

The number of specialist hospitals in Malaysia is greater than ever, and is still increasing. Medical tourism is being promoted by the Malaysian Government [19], and foreign patients prefer to come to private hospitals for treatment for many reasons. Medical proficiency in private hospitals ranks among the best in the region compared with public hospitals. Today, more than 225 private hospitals exist, of which about 115 hospitals are registered with the Association of Private Hospitals of Malaysia (APHM). This ranges from small specialty centres to multiple chain hospitals owned by big business giants.

In Malaysia, medicines provided by the government hospitals are not charged to the patient, so treatments must be as economical as possible and include the use of generic medicines. In private hospitals, generics usage seems to be low, and patients or insurance companies are required to pay for treatments. Limited data are available on the perception of consumers and general physicians about generics usage in Malaysia, but no data are available on the lag in generics usage in private hospitals compared with other healthcare sectors. This has led us to investigate the perception that medical practitioners working in private medical centres have of generic medicines to ascertain their skepticism towards generics usage. The results of this study can form the basis of a review of existing policies on generic medicine usage, and future plans for educational interventions.

Methods

Qualitative research is considered to be exploratory and can be used to make hypotheses, whereas quantitative studies are intended to test them. On the basis of available research, we considered qualitative research a suitable tool to initiate this investigation [20–22]. We surveyed a sample of specialists serving in privately owned medical centres to evaluate their perceptions of generic drugs, and to understand their concerns and barriers to usage.

Following institutional ethics committee authorization, private hospitals registered with APHM were contacted by letter requesting a survey on this topic. The request letters were sent to 95 hospitals registered with APHM. Thirty-nine hospitals did not respond. The human resources department or person in charge of 22 hospitals replied declined participation in this study. Institutions that agreed to participate permitted us to contact physicians directly or through their human resources department. Many doctors declined participation because of their busy schedule and were unable to spare time for interviews. Appointments were made with physicians who agreed on a suitable time and place, mostly in the doctor’s office. Written informed consent was obtained for each participant before the interview. Demographic information relating to each participant was collected using a self-completed questionnaire. For interviews, a semi-structured questionnaire comprising 16 questions under six themes in English was prepared after reviewing existing research and conducting groundwork discussions with a few physicians. Participants received no remuneration. During interviews, the researcher read the questions aloud to the physician to obtain free-flow thoughts; they were given full liberty to convey additional views on the topic at the end of the dialogue. Appropriate questions were asked when necessary during the interview. Each interview lasted about 10-25 minutes. The interviews were audio taped and transcribed verbatim. All the researchers then listened to tapes, analyzed the recordings, and carried out line-by-line transcripts for applicable content and themes. The identified themes were debated among the researchers. The interviews were conducted among a convenience sample of physicians until no new ideas or comments were received.

The interviews focused on the following topics: selection criteria of prescription medicine; knowledge and trust of generics; patients’ acceptance of generics; the effect of drug advertising, promotion and marketing on selection of prescription medicines; brand substitution by hospitals or community pharmacists; and strategies to boost generics’ prescription rate. The questionnaire is available on request from the corresponding author.

Results

Demographic data of participants

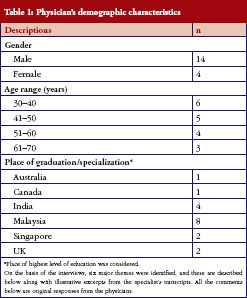

Eighteen physicians from different medical specialties were interviewed after signing an informed consent form. All of them worked in major, renowned private medical centres in Malaysia. Their demographic characteristics are presented in Table 1.

Theme 1: prescription patterns

Interviewees were asked which factors influenced their selection of originator or generic drugs when prescribing a medicine to their patients. The questions attempted to determine whether cost of medicine and drug manufacturer’s credibility were the only factors leading to the selection of prescription medicines or whether other factors were involved.

‘Generally, I prescribe branded medicines but the only thing that makes me switch to generics is the price’ (Specialist # 04).

‘First of all, it must be effective and I must be assured of quality of the product. If a patient asks for cheaper medication, I will prescribe generic [drug] which is usually cheaper than the innovator’ (Specialist # 12).

‘This (prescribing of generics) is always driven by complaints from patients about the high cost of medicines. When we fear that the patient will discontinue treatment because of the high cost, we switch to generics to ensure that they complete the course of treatment. Cost definitely influences my selections at times’ (Specialist # 16).

All participants were aware of the lower cost of generic drugs compared with originator brands. Most of them preferred to prescribe generics, when a patient could not afford originator product or they suspected that a patient might stop taking medication because of the high prescription price.

During discussions on the effect of the manufacturer’s credibility on the selection of prescription medicines, most physicians said that they selected the generic drug based on the pharmaceutical company’s reputation.

‘Yes, certain drugs are manufactured in some places where quality control is not as tight. Even if the drugs are registered in Malaysia, they are of no use if they don’t work. So definitely, I look for the manufacturer’s creditability’ (Specialist # 03).

‘Yes, if it is a well known company and has a wide range of products. If it is a multinational company and audited by various drug authorities like the US FDA, and European authorities, I will feel OK’ (Specialist # 09).

‘Yes, of course … their credibility and good bioequivalence studies … then of course … I will be using them’ (Specialist # 18).

Theme 2: awareness and trust of generics

When physicians were asked whether they actively prescribed generics, responses were varied. Five physicians claimed that they did not use generics in their practice. Other physicians explained their concerns over generics but were still prescribing them at a rate of 10–60%.

‘Hardly, I hardly ever prescribe generic medicines unless a patient cannot afford it’ (Specialist # 01).

‘Yes, I actively prescribe generic medications but with a caveat. Sometimes patients do not prefer them because patients say that my company allows for coverage of higher cost medications … why are you giving this generic medicine, which nobody has heard of … that is the caveat sometimes’ (Specialist # 06).

‘I only prescribe originator products for certain drugs. For antibiotics that have been on the market for a long time, I prescribe generic drugs, and the pharmacist can dispense whatever is available. But, with certain new drugs, I would prefer to stick with originator drugs, such as Sporanox for fungal infections. I would never use generic [drug] substitutes. I have personally experienced generic [drug] substitutes to Sporanox and they don’t work. Their efficacy is less compared with the originator drug, although I don’t have any evidence but it’s my experience’ (Specialist # 09).

When physicians were asked if they were encouraged to prescribe generic medication, and about the factors that motivated them to prescribe generic medicines, most of them denied any encouragement by their own hospital or Ministry of Health. The only factor that influenced them to prescribe cheaper versions to the originator was the patient’s socio-economic status. The comments were as follows:

‘Well, it is a private hospital. It is only the patient who will benefit from a cost saving and it depends on his affordability. If he cannot afford originals [originators], I will prescribe generics. With certain medicines, I always use originals [originators], such as clopidogrel after stent surgery, for example. Because the consequence of not using originator drugs to save on cost can be quite serious. If the patient is on diabetes medication and it does not work, the sugar [level] goes up but the patient is not in danger. If generic clopidogrel does not work, he can develop a clot or something, and the consequences are so severe that I cannot take risk. So, I always have to weigh the benefits against the harms to help me decide’ (Specialist # 04).

‘Not by the hospital or by Ministry of Health … only by the pharmaceutical companies, they will show us that cost has been reduced and the product is equally bioavailable so they tell us … why can’t we prescribe their product’ (Specialist # 08).

‘Mainly for socio-economic reasons. But, at times, if I am convinced that the original [originator] is superior, I will still use it despite the cost’ (Specialist # 11).

‘Hospital policy here is always to try to use the innovator drug as much as possible. In my practice, I also use innovator drugs as often as I can. Most requests for generic drugs are made by the patient … because of cost reasons’ (Specialist # 13).

The most common reason for supporting generics was cost, but some of the comments were surprising. Although physicians are using generics to a certain degree, they do have concerns about quality and efficacy.

‘Basically, the cost … you know that the cost of originator products are being manipulated or controlled by big pharmaceutical companies … sometimes it is difficult to maintain the cost of treatment’ (Specialist # 08).

‘Well … basically cost and sometimes ease of getting the medicine … as these generics are easily available’ (Specialist # 12).

‘Cost is the main factor; there is no other real reason. If I find over two to three months that there is no efficacy, I switch to the originator’ (Specialist # 14).

When physicians were asked about their experience of generic medications, or whether any of their patients had experienced any health risks associated with a switch to generics, less than 25% of doctors admitted to trusting generics.

‘In the private sector, we intend to use the best available drugs on the market, and the best usually is the branded stuff. Just in case something happens to the patient, … it is easier for us to defend ourselves too, because I have used the best medicines and not any generic [drug]. Again it is very sad but it is part of defensive medicine and practice’ (Specialist # 01).

‘I don’t think so generic drugs are equally effective’ (Specialist # 02).

‘Have you heard of recent scandals of generic [drug] companies? Because of that, we doctors have realized that we can’t trust generic medicines at all. Unless there are proper studies, unless the data are very clean’ (Specialist # 03).

‘No … No … I prefer originals’ (Specialist # 05).

‘Yes, from certain companies and for certain products but not for all. There are many generic companies. Some are more reputable and show studies. Also I need to gain experience of using those medicines in my practice’ (Specialist # 15).

ot many physicians considered branded medicines to be superior to generics, but they believed them not to be identical. They believed that generic drugs differed in efficacy and quality. Few important aspects were highlighted:

‘Yes, but not always. I think that generics are good but all generics are not as good’ (Specialist # 03).

‘I don’t know whether they (innovator drugs) are superior but I would say that their quality control is probably more stringent and they are consistent. All clinical trials are carried out on innovator drugs, although generic drugs undergo bioequivalence testing, but it only demonstrates how the drug is distributed from a single batch and the pharmacodynamic effect is not tested. So, I am not sure if it is translatable. I would say a drug is consistent based on a trial’ (Specialist # 04).

‘Not really. The drug is the same so how can it be superior. This is my personal opinion … maybe … I have experienced that manufacturers of patented medicines follow good distribution practices and follow guidelines for storage and distribution, but generics send their medicines using regular courier companies with no storage control. Generics are effective but there is variation in effect some times. I presume that this is due to exposure to high heat while being transported. It might reduce their efficacy. In my experience, generics companies do not follow good distribution practice because they want to lower their costs’ (Specialist # 07).

‘I believe … I trust so-called originator drugs as they spend their money on proving the efficacy of their drugs. They have published their papers and I trust the evidence given by them so sometimes you cannot extrapolate to generics, so I still trust originators’ (Specialist # 09).

‘In terms of quality control, they are probably better. They are superior in terms of studies and evidence because most of the studies that have been conducted have used innovator [drug] products. Generics just tend to do bioequivalence studies and we assume that they are equal’ (Specialist # 16).

Interviewees were questioned about the bioequivalence criteria required by the National Pharmaceutical Control Bureau (NPCB), Malaysia, for generic medicines, and they seemed to have a fair idea about its purpose; however, they lacked understanding of the process of developing and formulating the drug product. A few doctors complained about the efforts of generics companies to promote their bioequivalent products.

‘Yes, I do. Unfortunately, when the salesman of any generics manufacturer comes, they never show us their bioequivalence studies. Many generics companies are using ..amorphous form.. of Atorvastatin whereas innovator is ..crystalline.., they don’t provide us such information. They just talk about cost which is not our focus. They should talk about efficacy comparison between Amorphous and Crystalline’ (Specialist # 01).

‘When a medical representative shows me the bioequivalence study, I feel more comfortable to prescribe. If this study is published in a reputed medical journal and he shows me that … I will feel even more confident. They can conduct such studies in universities where a researcher who is independent can help them to compare their products and publish the results’ (Specialist # 06).

‘Yes … yes. These studies don’t serve 100% purpose but give me some liberty to prescribe generics’ (Specialist # 08).

‘Some of the generics companies have carried out bioequivalence testing but these studies have not been published and I have no access to their data. They claim that they have done the study but I cannot believe until it is published’ (Specialist # 09).

Theme 3: reception of generics by patients

Most physicians explained that their patients were willing to use generics because of cost reasons and also that patients left up to the doctor to prescribe whatever was best for them. This was not, however, the case among educated patients, those with comprehensive insurance coverage, or those who had previously had bad experiences with generic medicines.

‘This depends on the educational level of the patient. Those who are educated will ask us to prescribe the originator drug if cost is not an issue with them. Patients who have lower educational levels do not question us about the prescription. If, for cost reasons, I prescribe generics and they find a difference in efficacy, I explain to them. I am not anti-generics but there are issues that need to be addressed to make the doctor more confident when prescribing’ (Specialist # 01).

‘They don’t mind. I always ask them … do you want a good one or an average one … do you want an expensive one or a cheaper one … that´s how a patient understands it. Patients will ask me whether it will work effectively and I tell them it will. Many will choose generics but some prefer to choose the originator’ (Specialist #10).

‘They are blissfully ignorant. They believe that I give what is best for them’ (Specialist # 11).

‘Usually I don’t tell them. I feel that it is not necessary to tell them, I will prescribe them the best from my knowledge’ (Specialist # 16).

When physicians were asked about their experience of any clinical problems associated with switching to generics, most of them expressed concern about loss of efficacy.

‘Yes, sometimes you find that blood pressure control is not so good. Sometimes you find that diabetic control is not so good. Sometimes they (the patients) are fine with the originator drug and, when switched to the generic drug, they experience more side effects such as stomach discomfort and change in bowl habits. When you switch back to the originator, they are fine. I have seen this many times. Sometimes, a pharmacist recommends another generic saying that it works fine. So, I know that there is some difference between innovator and generics and also among generics. But, this is my experience, we cannot generalize’ (Specialist # 04).

‘I think there are no side-effects but, in some diabetes medication, I have seen that sugar control is not that good. Some patients come and complain that ‘doctor I am so good with my diet, I went to government hospitals and they only gave me generics but my sugar control is getting worse’. Now, they come to a private hospital for better treatment, and if you give them generics again, they don’t feel comfortable. Most of the time, private hospitals are blamed for not using generics. But, patients who have experienced generics in government hospitals, and were taking medicines for 5 years, now come here and expect something better. Then, we change the medication, use originators, and try to make things better for them’ (Specialist # 06).

‘Yes, I have experienced that a number of times. When we change from originator to generic or from one generic to another generic, patients have experienced clinical relapse or have become non-responsive. So, I will stick to one product. Like Methotrexate, I was using the originator and then switched to generics, and I could see loss of efficacy, so I strongly believe in these few drugs. I have confidence in generics only if the drug has been on the market for quite some time’ (Specialist # 09).

‘No, actually the side effect should be the same as it is drug related not drug product related and … yes … sometimes efficacy can be low‘ (Specialist # 17).

Theme 4: effect of drug promotion and marketing on selection of prescription medicine

Physicians denied the fact that drug advertising and marketing influenced their choice of medicine brands that they prescribed.

‘I am an evidence-based person. If you show me good evidence, I will use it. You show me some data; I am more than happy to try it out’ (Specialist # 01).

‘No … you cannot believe slogans and all that … it has to be study based’ (Specialist # 07).

‘Yes, I tend to believe companies with studies to support their products, no matter how beautiful the girl is on the packet!’ (Specialist # 15).

‘Well, it does affect, in a sense that you are more aware’ (Specialist # 18).

Theme 5: brand substitution by hospital pharmacists

None of the physicians were happy with pharmacists switching brands without first consulting them. In the first instance, they did not like the idea of the pharmacist altering their prescription if necessary; they want to be consulted before making any change.

‘I will not be happy. If they ask, I am willing to listen and can consider. If he has a free hand, I will not know what he has used? Based on a patient’s condition, I would like to use another drug if the prescribed drug is not available rather than using a generic [drug]’ (Specialist # 03).

‘I don´t like it. If I have written it, they have to dispense the same brand. If I want to use a generic [drug]. I will write the same. You know, switching without consulting can be dangerous. If something happens to the patient, who is responsible? You cannot substitute medicines without consulting the physician’ (Specialist # 04).

‘No, I would like to be told. It has been my experience that originals [originators] tend to work better. I will need to caution the patient about the decreased efficacy that may result from using generics’ (Specialist # 11).

Theme 6: strategies to increase the rate of generics prescribing

Physicians were asked to share their views on strategies to improve generics usage in private medical hospitals. Most of them were not happy to see just the bioequivalence study but wanted to see small-scale community studies at least, which compare the pharmacodynamic behaviour of the product against the originator.

‘Most of the doctors come from government practice to private hospitals, and are well aware of generics. Private hospital pharmacists should make generics available in the pharmacy. It will increase our generic prescription rate’ (Specialist # 02).

‘In developed countries, governments are saving billions of dollars by using generics, but they might have better policies for generic introduction. But again, it is pharmacokinetics and not pharmacodynamics. I recommend that there should be a small trial along with a bioequivalence study to boost doctor’s confidence in generics’ (Specialist # 04).

‘I think they should come up with a bioequivalence and clinical intervention study. It will increase doctor’s’ confidence. For example, in my Master’s thesis, I used a generic Methotrexate and produced the results. This kind of study of a generic drug will give me more confidence for future use’ (Specialist # 09).

‘Why do you want to increase generics? Branded are good. These companies are doing lots of research, and they need money to do that. In private hospitals, you cannot increase usage because GPs have already tried generics on patients. I know, there are good generic companies across the world but what about those backyard companies?’ (Specialist # 15).

Discussion

The semi-structured interviews conducted with physicians provided insight into the perceptions of medical specialists about the use of generic drugs. We explored the opinions, awareness, and attitude of physicians towards the selection of prescription medication. Cost is the primary factor influencing the prescription of generics, and this is linked to increased adherence to treatment regimens by patients who otherwise would not be able to afford originator drugs [12, 13]. Use of generic drugs can significantly reduce healthcare expenditure, and this was acknowledged by the physicians involved in the study.

The results of our study are consistent with those in the international literature. The majority of specialists were positive about generics substitution but cynical about their quality in terms of efficacy and safety for some drug categories [23, 24]. Few of the physicians acknowledged that all available products on the market are approved and registered with NPCB. However, one of their main concerns is loss of efficacy resulting from a switch to generics and the variability among generics and between batches of a generic drug product, which they have experienced in their practice. Physicians rely on the manufacturer’s credibility, their research and development capabilities, and also their own experience with a particular generic drug product, as the basis for prescribing. Drugs manufactured by a multinational generic company or a renowned local company are much preferred over drugs from a small-scale generics manufacturer. They presume that quality-control measures undertaken by innovator or multinational companies are stricter. Concerns were raised about the lack of provision by the Ministry of Health to audit imported medicines and bioequivalence centres abroad. Physicians felt more confident to prescribe imported drug products from a company if it is audited by other health regulators, such as the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the European Medicines Agency (EMA).

About 25% of specialists in private hospitals rejected the use of generics because of their experience with such products, or because of the fact that patients had been prescribed generics by general practitioners before referral to private hospital. Failure of treatment at primary care, however, can be attributed to lack of diagnostic facilities rather than medication prescribed. Seventy-five per cent of specialists were using generics to some extent but expressed concerns. Key criteria for selecting prescription medicines were: (i) the patient’s socio-economic status; (ii) level of education; (iii) level of employer healthcare cover, insurance cover, or both; and (iv) the patient’s ability to pay. Ease of access to generics is another reason indicated by some physicians for their selection.

Although physicians did not believe that originator products were superior to generics, most of them had some ‘not so nice’ experiences with generics. Inconsistent quality and loss of efficacy was the major concern, and most physicians restricted themselves to prescribing only originator products if the patient was in a critical condition or in the early phase of treatment. Physicians preferred to switch to generic medications once the patient was stable or on long-term treatment.

Other factors influencing the selection of originator drugs over generics were lack of evidence-based studies and failure of generics companies to follow ‘good distribution practices’. Physicians believe that a bioequivalence study is an ostensible tool to demonstrate equivalence between reference and generic drug product. Apart from pharmacokinetic equivalence demonstration through bioequivalence, it was felt that small community-based studies by independent researchers should be available if a controlled clinical trial was not feasible for cost reasons. The possible reason for variability or loss of efficacy mentioned by two physicians was storage conditions following shipping of generics for distribution. They observed that manufacturers of originator drugs followed good distribution practices, and ensured that drugs were shipped appropriately under recommended conditions, whereas generics manufacturers intended to keep costs down and did not follow these regulations so rigorously. Physicians also commented on strict quality control of input materials, process, and final products carried out by originators compared with generics companies. They felt that this lack of control among generics companies resulted in variability among batches of generics and also between generic and innovator drug products. Physicians emphasized that their views were personal and based on their own experience. Compared with previously published studies [21], we found that physicians were well informed about bioequivalence and its importance in proving equivalence between two products. They were not convinced that a pharmacokinetic study on a single batch was sufficient to prove therapeutic equivalence, and felt that some pharmacodynamic proof was needed to demonstrate equivalence. They also expressed concerns over research centres in some countries conducting bioequivalence studies, and recommended that studies should be conducted by an independent body. Physicians also commented on the marketing strategies of local generics companies, stating that their medical representatives based the promotion of products on cost comparisons rather than bioequivalence or other studies. The physicians preferred to see a published bioequivalence study or leaflets containing study results to boost their confidence in the product.

Only a few physicians mentioned to their patients if they were prescribing a generic or originator drug, based on the assumption that patients rely on the physician to offer them the best treatment. If the physician, however, mentions to the patient that he is prescribing a generic drug, and conveys his opinion about efficacy issues, he may bias the patient’s opinion, resulting in a product complaint about the efficacy of the product.

While discussing their clinical experience on switching to generics, most physicians relayed their concern, or their patients’ concern, about loss of efficacy or the occurrence of a relapse. This was more commonly observed with newer or cardiovascular-related products. Physicians felt more confident in using established generic drug products, especially antibiotics.

Choice of prescription medicines was only influenced by marketing and advertising if results were based on the best available evidence. A recommendation from physicians to generics companies is to promote their products on the basis of studies rather than cost benefits. Although brand switching by pharmacists is being promoted around the globe, none of the physicians we interviewed had good feelings about it. If the prescription was for a branded drug, it was their preference that the dispensed medicine should be the same. Pharmacists are only permitted to switch between generic drugs.

Many physicians involved in this study did not have good experiences with generics, but could not suggest ways to improve generics usage in private medical hospitals in Malaysia. The only recommendation received was for generics manufacturers to improve marketing by focusing on discussion about the studies conducted.

Limitations of the study

Although the study was conducted in different states of Malaysia, the number of physicians involved could not represent the views of the whole community. As the physicians interviewed were practising in private hospitals, some were skeptical about participating in the study. Therefore, a larger population could not be studied, but we continued to interview until responses reached saturation level.

Conclusion

In this study, we report various issues that have not been previously discussed, including perception of physicians working within private medical hospitals in Malaysia. Physicians in these facilities did not view generic medicines favourably. In fact, both generic and branded drug products are being manufactured under similar current good manufacturing practice (cGMP) conditions as required for innovator companies. All generics manufacturing, packaging, and testing sites must pass the same quality standards as those of branded drugs, and the generic drug products must meet the same specifications as any brand-name drug product. Many generic drugs are made in the same manufacturing plants as brand-name drug products. Hence, these low-priced generics do not essentially interpret to be of lower quality as few physicians commented. The lower costs of generics are achievable because of exemption of costly preclinical, clinical trials and bioavailability study requirements [25]. It is necessary to communicate to doctors about the role of NPCB in regulating drugs based on quality, safety and efficacy. Similarly, NPCB also conduct good distribution practices audits to warranty proper distribution of medicines. To improve generics usage, it is prudent that generics manufacturers should train their medical representatives to explain the available bioequivalence study to physicians. Also if possible, manufacturers should support their findings with small community studies conducted by a researcher from a university or a hospital. This will certainly improve a physician’s trust in the product.

The concerns about imported generic medicines may be genuine as NPCB is not auditing overseas manufacturers. They still accept GMP certification from other authorities for registration of the imported products. Bioequivalence centres in Malaysia are accredited by NPCB but overseas centres were never audited in the past. Many products on the market may have been registered under old regulations and do not comply with current requirements. NPCB is making efforts to control these kind of products by a process of re-registration whereby the manufacturer has to submit a bioequivalence study if one has not previously been conducted.

One of the astonishing aspects discovered was attitude of physicians versus pharmacists. Studies from various countries indicate that pharmacists are generally in favour of generics substitution and view generic medicines as being efficacious and safe [17]. Pharmacists can play a major role in promoting generics usage. Hence, we strongly recommend improving the cooperation between doctors and pharmacists. Apart from awareness-raising campaigns to increase trust in generic medications, it is also recommended that pharmaceutical manufacturers in Malaysia invest in quality-assurance programmes.

It is important to change the physicians’ perception of promoting generics. In addition to implementing generic drug usage policies for private hospitals in Malaysia, this can be achieved through improved marketing and promotion of generic drug products as suggested above. High quality educational intervention programmes are required to provide information and knowledge to physicians about generics.

The Malaysian Ministry of Health is attempting to reach the public through programmes such as the Generic Medicines Awareness Programme, which is promoting generics through road shows that educate the general public and convey the benefits of generic drugs over innovator drugs in terms of cost, while assuring them that quality and efficacy is paramount. It will be helpful if a patient can request generics when they visit such medical centres. The involvement of patients in decision making allows them to choose a preferred medicine, and this would result in improved adherence and significant savings in healthcare cost. In Malaysia, private sector expenditures are household OOP (nearly 77%) followed by private insurance and employers that arrange health care for their employees. These OOP payments in Malaysia are twice that of OOP averages in high-income countries, at 37% of private-sector spending [26]. Increased generics usage in the private sector will help to overcome situations that may result in calamitous financial burden.

The insight gained from physicians is useful for generics manufacturers, health organizations, and policymakers to improve the status of generics and change the perception of physicians in private medical hospitals in Malaysia.

Acknowledgement

The authors wish to thank all the physicians who voluntarily participated in this study.

Funding sources

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Authors

Rohit Kumar1, MPharm

Mohamed Azmi Ahmad Hassali1, PhD

Navneet Kaur2, PhD

Muhamad Ali SK Abdul Kader3, MD

1Department of Social and Administrative Pharmacy, School of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Universiti Sains Malaysia, Minden, 11800 Penang, Malaysia

2Department of Physiology and Pharmacology, School of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Universiti Sains Malaysia, Minden, 11800 Penang, Malaysia

3Department of Cardiology, Hospital Pulau Pinang, Jalan Residensi, 10990 Penang, Malaysia

References

1. Godman B, Wettermark B, Bishop I, et al. European payer initiatives to reduce prescribing costs through use of generics. Generics and Biosimilars Initiative Journal (GaBI Journal). 2012;1(1):22-7. doi:10.5639/gabij.2012.0101.007

2. Godman B, Shrank W, Wettermark B, et al. Use of generics—a critical cost containment measure for all healthcare professionals in Europe? Pharmaceuticals. 2010;3(8):2470-94. doi 10.3390/ph/3082470

3. Godman B, Shrank W, Andersen M, et al. Comparing policies to enhance prescribing efficiency in Europe through increasing generic utilization: changes seen and global implications. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2010;10(6):707-22.

4. World Health Organization. Health Systems Financing. Cameron A and Laing R. Cost savings of switching private sector consumption from originator brand medicines to generic equivalents. World Health Report. (2010). Background Paper, 35 [homepage on the Internet]. 2010 Nov 17 [cited 2014 Mar 31]. Available from: http://www.who.int/healthsystems/topics/financing/healthreport/35MedicineCostSavings.pdf

5. Cameron A, Mantel-Teeuwisse AK, Leufkens HG, et al. Switching from originator brand medicines to generic equivalents in selected developing countries: how much could be saved? Value Health. 2012;15(5):664-73.

6. Araszkiewicz AA, Szabert K, Godman B, et al. Generic olanzapine: health authority opportunity or nightmare? Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2008;8(6):549-55.

7. Brems Y, Seville J, Baeyens J. The expanding world market of generic pharmaceuticals. Journal of Generic Medicines. 2011;8(4):227-39.

8. Kaplan WA, Ritz LS, Vitello M, et al. Policies to promote use of generic medicines in low and middle income countries: a review of published literature 2000-2010. Health Policy. 2012;106(3):211-24.

9. Malaysia Pharmaceuticals and Healthcare Report Q2 2014. Business Monitor International.

10. Shafie AA, Hassali MA. Price comparison between innovator and generic medicines sold by community pharmacies in the state of Penang, Malaysia. Journal of Generic Medicines. 2008;6(1):35-42.

11. Chong CP, Hassali MA, Bahari MB, et al. Evaluating community pharmacists’ perceptions of future generic substitution policy implementation: a national survey from Malaysia. Health Policy. 2010;94(1):68-75.

12. Ping CC, Bahari MB, Hassali MA. A pilot study on generic medicine substitution practices among community pharmacists in the State of Penang, Malaysia. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2008;17(1):82-9.

13. Shrank WH, Hoang T, Ettner SL, et al. The implications of choice: prescribing generic or preferred pharmaceuticals improves medication adherence for chronic conditions. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(3):332-7.

14. Shrank WH, Cox ER, Fischer MA, et al. Patients’ perceptions of generic medications. Health Aff (Millwood). 2009;28(2):546-56.

15. Healthcare is one of Malaysia’s National Key Economic Area (NKEA) for wealth creation. Asia-Pacific Pharma Newsletter. 2011;6:15.

16. Chua GN, Hassali MA, Shafie AA, et al. A survey exploring knowledge and perception of general practitioners towards the use of generic medicines in the northern state of Malaysia. Health Policy. 2010;95(2-3):229-35.

17. Hassali MA, Shafie AA, Chong CP, et al. Community pharmacist’s perceptions towards the quality of locally manufactured generic medicines: a descriptive study from Malaysia. Journal of Applied Pharmaceutical Science. 2012;02(01):56-60.

18. Fatokun O, Ibrahim MIM, Hassali MAA. Generic industry’s perceptions of generic medicines policies and practices in Malaysia. Journal of Pharmacy Research. 2013;7(1):80-4.

19. Pocock NS, Phua KH. Medical tourism and policy implications for health systems: a conceptual framework from a comparative study of Thailand, Singapore and Malaysia. Global Health. 2011;7:12. doi: 10.1186/1744-8603-7-12.

20. Kairuz T, Crump K, O’Brien A. An overview of qualitative research. Pharm J. 2007 Mar;277:312-4.

21. Hassali MA, Kong DCM, Stewart K. Generic medicines: perceptions of general practitioners in Melbourne, Australia. Journal of Generic Medicines. 2006;3(3):214-25.

22. Britten N, Jones R, Murphy E, et al. Qualitative research methods in general practice and primary care. Fam Pract. 1995;12(1):104-14.

23. Tsiantou V, Zavras D, Kousoulakou H, et al. Generic medicines: Greek physicians’ perceptions and prescribing practices. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2009;34(5):547-54.

24. Heikkilä R, Mantyselkä P, Hartikainen-Herranen K, et al. Customers’ and physicians’ opinions of experiences with generic substitution during the first year in Finland. Health Policy. 2007;82(3): 366-74.

25. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Facts about generic drugs. 2012 [homepage on the Internet]. [cited 2014 Mar 31]. Available from: http://www.fda.gov/drugs/resourcesforyou/consumers/buyingusingmedicinesafely/understandinggenericdrugs/ucm167991.htm

26. Malaysia Health System Review. Health Systems in Transition. 2013;3(1). Available from: http://www.wpro.who.int/asia_pacific_observatory/hits/series/Malaysia_Health_Systems_Review2013.pdf

|

Author for correspondence: Rohit Kumar, MPharm, Department of Social and Administrative Pharmacy, School of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Universiti Sains Malaysia, Minden, 11800 Penang, Malaysia |

Disclosure of Conflict of Interest Statement is available upon request.

Copyright © 2014 Pro Pharma Communications International

Permission granted to reproduce for personal and non-commercial use only. All other reproduction, copy or reprinting of all or part of any ‘Content’ found on this website is strictly prohibited without the prior consent of the publisher. Contact the publisher to obtain permission before redistributing.