The challenge for drug shortage: lessons learned from the quality issues of Japanese generic drug companies

Published on 23 August 2024

Generics and Biosimilars Initiative Journal (GaBI Journal). 2024;13(3):163-6.

Abstract: |

Introduction

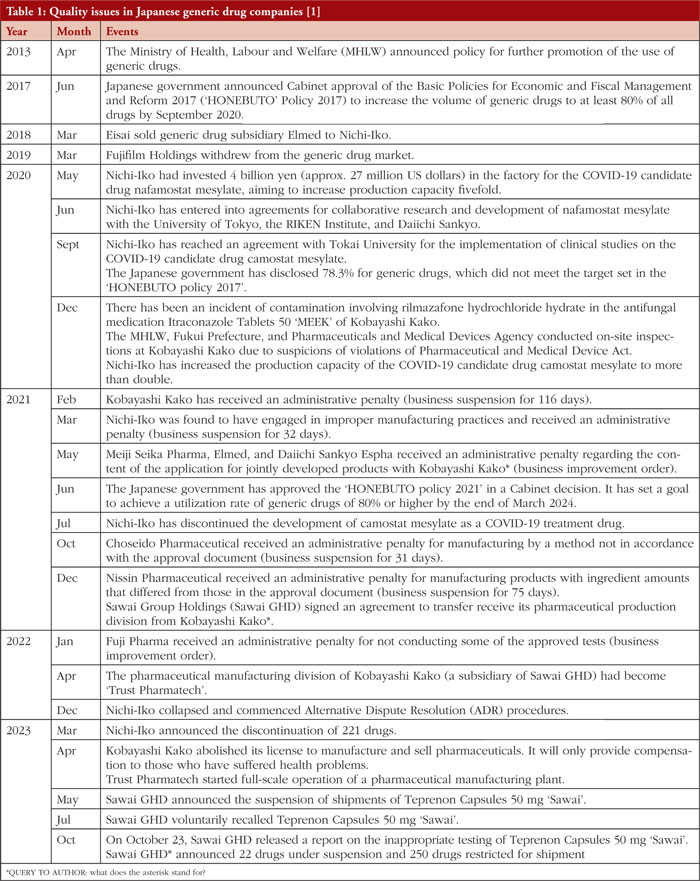

On 23 October 2023, Sawai Group Holdings (Sawai GHD), a prominent Japanese manufacturer of generic pharmaceuticals, disclosed that the stability monitoring for their teprenone capsules 50 mg ‘Sawai’ was improperly conducted [1]. This announcement follows a similar incident in July 2023, when Nichi-Iko ceased the sale of 258 generic drugs [2]. Subsequent reports from various generic drug manufacturers indicate reduced sales or product discontinuations, see Table 1. Recognizing the significant impact of these incidents on medical care, the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (MHLW) has mandated the replacement of the responsible person for manufacturing under the Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Act [1]. As a result, the head of quality assurance at Sawai GHD resigned.

In May 2023, following the announcement of the shipment halt of teprenone capsules 50 mg ‘Sawai’, it was discovered in April 2023 that there had been misconduct at the Kyushu plant during the dissolution tests for stability monitoring. Results were falsified to pass by repacking the product into new capsules. Subsequently, a good manufacturing practice (GMP) investigation was conducted by the Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency (PMDA) in July, and the product was determined to be GMP non-compliant in August [1]. It took approximately five months until the announcement in October, during which time healthcare providers were compelled to recall teprenone, switch to an alternative drug, and explain the change to patients.

Indeed, even before these cases, drug shortages had become commonplace in Japan, often preventing vital medications from reaching patients in need [3]. This issue was particularly highlighted after the 2020 controversy involving another generic drug company, Kobayashi Kako Co, Ltd. The company faced a crisis when its oral antifungal drug, itraconazole, was contaminated with a sedative, leading to 245 patients experiencing adverse effects, including two fatalities from unconsciousness while driving. Investigations revealed that since 2005, the company had been using unauthorized manufacturing procedures [4]. There is concern that the latest developments may exacerbate the existing shortages.

The primary author, who works in a local pharmacy, has observed that GMP violations by Japanese generic pharmaceutical companies are worsening the drug shortage in the country [5]. Even if one generic pharmaceutical company ceases sales and withdraws, many other companies do not have the capacity to meet the increased demand, resulting in unresolved drug shortages [6]. This vicious cycle is causing patients and healthcare providers to lose faith in generic drugs, leading them to increasingly prefer branded drugs [7]. To mitigate further deterioration, a thorough review of Japan’s past healthcare policies and systems is necessary [8].

The generic pharmaceutical industry is confronting increasingly poor profitability, unfolding in two phases. First, since 2013, government advocacy for generic drugs may have unintentionally prompted manufacturers to prioritize supply stability over product quality. Then, by 2018, the dual impact of reduced drug pricing and rising costs jeopardized the financial sustainability of generic drug production [9]. This predicament worsened with the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, when substantial investments to manage the crisis further strained the limited resources of these manufacturers.

The results of the policies promoting the use of generic drugs since 2013

In 2013, the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare created a ‘Roadmap for Further Promotion of Generic Drugs’, aiming to build a stable supply system for generic drugs. The goal was to increase their usage from 25% to 60% by 2018 [10]. Further, in 2017, the Japanese government set an objective to reach an 80% usage rate for generic drugs within three years [11]. By 2020, the rate had reached 78.3%, prompting the government to extend the 80% target to the end of March 2024. During this period, policies were enacted both to reduce drug prices and to incentivize healthcare institutions to prescribe generics [11]. Consequently, these measures led to some major pharmaceutical companies exiting the generic market in 2018 and 2019 [12].

In high-income countries, one of the primary causes of drug shortages is the difficulty in maintaining low generic drug prices amidst rising manufacturing costs [13]. Germany serves as an example where the pricing of generic drugs, based on the healthcare system, does not align with current difficulties surrounding generic drugs, leading to drug shortages [14]. Germany, which has universal medical insurance coverage like Japan, is the leading consumer of generic drugs in Europe, with generics making up 83.4% of all drug usage [15]. In the German healthcare insurance system, reimbursements for generic drugs are set at the price of the cheapest available drugs. Consequently, the increasing manufacturing costs have forced numerous pharmaceutical companies to exit the market, resulting in a critical drug shortage [14]. Learning from the case of Germany, one strategy to resolve drug shortages could be to establish a framework that supports the costs associated with generic drugs [16].

The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the sustainability of generic drug production and supply

The COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated existing drug sustainability challenges in Japan, where drug shortages, such as that of cefazolin, were already a concern before the pandemic began [17]. The most critical instance causing a lack of cefazolin occurred in 2018, with an interruption in the supply of its active pharmaceutical ingredient (API). This disruption led to a pronounced scarcity of cefazolin, especially impacting perioperative care [18]. In response, the MHLW, alongside the Japan Medical Association and the Japan Pharmacists Association, urged Nichi-Iko to secure a consistent supply of cefazolin sodium injections [17]. Subsequently, during the COVID-19 pandemic, lockdowns in major API-supplying countries, such as India [19] and China [20], led to a significant global drug shortage [21]. During this challenging time, Nichi-Iko pursued research on the potential effects of camostat mesylate and nafamostat mesylate on COVID-19 in collaboration with universities and research institutions and made substantial investments in expanding their manufacturing facilities, see Table 1.

Despite Nichi-Iko’s investment and research into drugs like camostat mesylate and nafamostat mesylate for COVID-19 treatment [22], these medications were not endorsed in Japan’s COVID-19 clinical practice guidelines. Consequently, Nichi-Iko may not have seen a return on their investment. Nichi-Iko’s subsequent GMP violations compounded their financial losses, culminating in bankruptcy and an application for alternative dispute resolution (ADR) at the end of 2022, see Table 1 [23].

Since 2018, the policy for reducing pharmaceutical prices changed from once every two years to annually [24]. As a result, the number of unprofitable generic drug items increased, and about two-thirds of Sawai GHD’s own pharmaceuticals became unprofitable [25]. Facing these circumstances, Sawai GHD improved its manufacturing capacity and maintained a stable supply by acquiring Kobayashi Kako’s manufacturing plant in 2021 [26]. This financially unsustainable expansion of investments might have led to negligence in quality control at Sawai GHD.

Japanese government’s policy to promote the use of generic drugs and the decline in corporate competitiveness

While Japan was advancing its policy to promote the use of generic drugs, it is possible that the growth capacity of generic pharmaceutical companies was reaching its limits. For example, according to the integrated report published by Sawai GHD [27], the annual number of tablets sold had not shown growth from about 10 billion tablets since 2017 until the acquisition of Kobayashi Kako’s factory. Additionally, the acquisition ventures of American subsidiaries, pursued by Sawai GHD and Nichi-Iko with the aim of overseas expansion and business growth, failed [28]. Nichi-Iko acquired Sagent Pharmaceuticals in 2016, followed by Sawai GHD’s acquisition of Upsher-Smith in 2017. However, both companies reported losses in 2022 due to deteriorating performance [28]. The cause is believed to be their inability to compete in the price competition in the US generic drug market [28].

In Japan, various policy measures have been implemented to increase the usage rate of generic drugs [29]. A system exists where medical institutions can earn revenue by prescribing generic drugs, and pharmacies can earn revenue by dispensing a certain percentage of generic drugs. As a result, generic companies were in a situation where their products were used without the need for significant sales activities. This may have led to a decrease in competitiveness compared to foreign generic drug companies.

Conclusion

In Japan, which is among the most aged societies globally, reducing medical costs is a pressing issue. To mitigate the drug shortage crisis, there is a need for competitive generic drug companies that can ensure a stable supply, maintain high quality, and offer affordable prices. In February 2024, Sawai GHD announced its intention to restructure its corporate governance, which includes a reevaluation of pharmaceutical quality assessment [30]. On the other hand, healthcare professionals may have been blindly following policies aimed at promoting the use of generic drugs. Moving forward, it is crucial to monitor the management status of generic pharmaceutical companies and evaluate their ability to maintain a stable supply. It is hoped that the recent issues involving generic pharmaceutical companies, including Sawai GHD, will serve as practical lessons for both the pharmaceutical industry and the healthcare sector going forward.

Acknowledgement

We acknowledge the use of ChatGPT by OpenAI for assistance in language editing and enhancing the clarity of this manuscript.

Funding sources No funding was received for this work.

Competing interests: TH has no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose. AO receives personal fees from MNES (Medical Network Systems) Inc, and has received personal fees from Becton Dickinson and Company, Taiho Pharmaceutical Co, Ltd, Pfizer, and Kyowa Kirin Inc, outside the submitted work. HS has received personal fees from Taiho Pharmaceutical Co, Ltd, outside the submitted work. TT receives personal fees from MNES (Medical Network Systems) Inc, and has received personal fees from Bionics Inc, outside the submitted work.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Authors

Takanao Hashimoto1, PhD

Akihiko Ozaki2, MD, PhD

Hiroaki Saito3, MD

Erika Yamashita4

Tetsuya Tanimoto5, MD

Mihajlo Jakovljevic6,7,8, MD, PhD

1Kenkodo Pharmacy, Osaki, Miyagi, Japan

2Breast and Thyroid Center, Jyoban Hospital of Tokiwa Foundation, Iwaki, Fukushima, Japan

3Department of Internal medicine, Soma Central Hospital, Soma, Fukushima, Japan

4Medical Governance Research Institute, Minato-ku, Tokyo, Japan

5Navitas Clinic, Tokyo, Japan

6UNESCO-TWAS, Trieste, Italy

7Shaanxi University of Technology, Hanzhong, China

8Department of Global Health Economics and Policy, University of Kragujevac, Serbia

References

1. Sawai Group Holdings. [Administrative penalties from the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare, Osaka Prefecture and Fukuoka Prefecture, 2023]. Japanese. [homepage on the Internet]. [cited 2024 Aug 8]. Available from: https://www.sawai.co.jp/release/pdf/624

2. Nichi-iko. [Discontinuation of 258 products, 2023]. Japanese. [homepage on the Internet]. [cited 2024 Aug 8]. Available from: https://www.nichiiko.co.jp/medicine/files/20230711cI0.pdf

3. Jakovljevic MB, Nakazono S, Ogura S. Contemporary generic market in Japan – key conditions to successful evolution. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2014;14:181-94. doi:10.1586/14737167.2014.881254

4. Kosaka M, Ozaki A, Kaneda Y, Saito H, Yamashita E, Murayama A. Generic drug crisis in Japan and changes leading to the collapse of universal health insurance established in 1961: the case of Kobayashi Kako Co. Ltd. Cost Eff Resour Alloc. 2023;21:35. doi:10.1186/s12962-023-00441-z

5. Izutsu KI, Ando D, Morita T, Abe Y, Yoshida H. Generic drug shortage in Japan: GMP noncompliance and associated quality issues. J Pharm Sci. 2023;112:1763-71. doi:10.1016/j.xphs.2023.03.006

6. Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. [Current status of the generic drug industry]. Japanese. [homepage on the Internet]. [cited 2024 Aug 8]. Available from: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/content/10807000/001127776.pdf

7. Jakovljevic M, Wu W, Merrick J, Cerda A, Varjacic M, Sugahara T. Asian innovation in pharmaceutical and medical device industry – beyond tomorrow. J Med Econ. 2021;24:42-50. doi:10.1080/13696998.2021.2013675

8. Sapkota B, Palaian S, Shrestha S, Ozaki A, Mohamed Ibrahim MI, Jakovljevic M. Gap analysis in manufacturing, innovation and marketing of medical devices in the Asia-Pacific region. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res, 2022;22(7):1043-50. doi:10.1080/14737167.2022.2086122

9. Jakovljevic M, Matter-Walstra K, Sugahara T, Sharma T, Reshetnikov V, Merrick J, et al. Cost-effectiveness and resource allocation (CERA) 18 years of evolution: maturity of adulthood and promise beyond tomorrow, Cost Eff Resour Alloc. 2020;18:15. doi:10.1186/s12962-020-00210-2

10. The Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. [Roadmap for further promotion of generic drug use. 2013]. Japanese. [homepage on the Internet]. [cited 2024 Aug 8]. Available from: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/stf/shingi/2r9852000002yu25-att/2r9852000002zb0m_1.pdf

11. The Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. [Promotion of the use of generic drugs and biosimilars]. Japanese. [homepage on the Internet]. [cited 2024 Aug 8]. Available from: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/stf/seisakunitsuite/bunya/kenkou_iryou/iryou/kouhatu-iyaku/index.html

12. [Generic products industry restructuring]. 2018. Japanese. AnswersNews. Available from: https://answers.ten-navi.com/pharmanews/14554/

13. Shukar S, Zahoor F, Hayat K, Saeed A, Gillani AH, Omer S, et al. Drug shortage: causes, impact, and mitigation strategies. Front Pharmacol 2021;12:693426. doi:10.3389/fphar.2021.693426

14. Kinkartz S. German Health Ministry confronts drug shortage. 2023. DW. Available from: https://www.dw.com/en/health-ministry-confronts-germanys-dire-medicine-shortage/a-64733080

15. OECD Health at a glance 2023 country note. Germany, 2023 [homepage on the Internet]. [cited 2024 Aug 8]. Available from: https://www.oecd.org/germany/health-at-a-glance-Germany-EN.pdf

16. Jakovljevic M, Ogura S. Health economics at the crossroads of centuries – from the past to the future. Front Public Health. 2016;4:115. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2016.00115

17. Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. [Conference on securing stable pharmaceutical products, 2020]. Japanese. [homepage on the Internet]. [cited 2024 Aug 8]. Available from: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/content/10807000/000644861.pdf

18. Honda H, Murakami S, Tokuda Y, Tagashira Y, Takamatsu A. Critical national shortage of cefazolin in Japan: management strategies. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71:1783-9. doi:10.1093/cid/ciaa216

19. Chattu VK, Singh B, Kaur J, Jakovljevic M. COVID-19 Vaccine, TRIPS, and Global Health Diplomacy: India’s role at the WTO Platform. Biomed Res Int. 2021;2021:6658070. doi:10.1155/2021/

6658070

20. Jin H, Li B, Jakovljevic H. How China controls the Covid-19 epidemic through public health expenditure and policy? J Med Econ. 2022;25:437-49. doi:10.1080/13696998.2022.2054202

21. Japan Pharmaceutical Trader’s Association. [The impact of COVID-19 on the active pharmaceutical ingredients supply chain, 2020]. Japanese. [homepage on the Internet]. [cited 2024 Aug 8]. Available from: https://www.japta.or.jp/wp-content/uploads/COVID-19.pdf

22. The Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. [The Coronavirus COVID-19 Clinical Practice Note, 9th ed., 2023]. Japanese. [homepage on the Internet]. [cited 2024 Aug 8]. Available from: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/content/000936655.pdf

23. Nichi-iko. [Turnaround ADR procedures. 2022]. Japanese. [homepage on the Internet]. [cited 2024 Aug 8]. Available from: https://www.nichiiko.co.jp/company/press/detail/5709/1694/4541_20221228_03.pdf

24. [Drug price reform, 2018]. Japanese. [homepage on the Internet]. [cited 2024 Aug 8]. Available from: https://www5.cao.go.jp/keizai-shimon//kaigi/special/reform/wg1/20191114/shiryou2-1.pdf

25. Mixonline. [Responding to stable supply in the face of soaring prices, 2022]. Japanese. [homepage on the Internet]. [cited 2024 Aug 8]. Available from: https://www.mixonline.jp/tabid55.html?artid=73325

26. Sawai Group Holdings. [Sawai signs transfer agreement with Kobayashi-Kako, 2021]. Japanese. [homepage on the Internet]. [cited 2024 Aug 8]. Available from: https://www.sawaigroup.holdings/release/detail/13

27. Sawai Group Holdings. [integrated report]. Japanese. [homepage on the Internet]. [cited 2024 Aug 8]. Available from: https://www.sawaigroup.holdings/ir/library/integrated_report/

28. Maeda Y. [Was the generic manufacturer’s entry into the U.S. a failure? -Sawai and Nichi-Iko make a final loss due to impairment]. AnswersNews. Japanese. Available from: https://answers.ten-navi.com/pharmanews/23206/

29. Cabinet Office, Government of Japan. [Measures to further promote the use of generic drugs]. Japanese. [homepage on the Internet]. [cited 2024 Aug 8]. Available from: https://www5.cao.go.jp/keizai-shimon/kaigi/special/reform/committee/20200323/shiryou4_2.pdf

30. Sawai Group Holdings. [Progress of Corporate Culture Reform Project, 2021]. Japanese. [homepage on the Internet]. [cited 2024 Aug 8]. Available from: https://www.sawai.co.jp/important_news/detail/17

|

Author for correspondence: Takanao Hashimoto, PhD, Kenkodo Pharmacy, Osaki, Miyagi, Japan; 1-6-2 Furukawaekimaeodori, Osaki, Miyagi, 989-6162, Japan |

Disclosure of Conflict of Interest Statement is available upon request.

Copyright © 2024 Pro Pharma Communications International

Permission granted to reproduce for personal and non-commercial use only. All other reproduction, copy or reprinting of all or part of any ‘Content’ found on this website is strictly prohibited without the prior consent of the publisher. Contact the publisher to obtain permission before redistributing.