Key factors for successful uptake of biosimilars: Europe and the US

Published on 2022/08/19

Generics and Biosimilars Initiative Journal (GaBI Journal). 2022;11(3):112-24.

|

Introduction: Biosimilars were first introduced in Europe in 2006 and then in the US in 2015. An online webinar on the successful uptake in Europe and the US was held to discuss measures taken for improving biosimilar uptake, and trends in uptake. |

Submitted: 9 August 2022; Revised: 16 September 2022; Accepted: 22 September 2022; Published online first: 26 September 2022

Introduction

In collaboration with the Alliance for Safe Biologic Medicines (ASBM), the Generics and Biosimilars Initiative (GaBI) organized and hosted the first in a series of webinars on biosimilars entitled ‘Key factors for successful uptake of biosimilars: Europe and the US’. This webinar set out to discuss measures taken for improving biosimilar uptake, trends in uptake, and the potential role to be played by healthcare providers and patients in Europe and the US.

Biosimilars have been in the market for 16 years since their first launch in 2006 in Europe. At the time of the webinar, there were 88 approvals (including 16 biosimilars withdrawn after approval) in the EU [1] and 36 in the US [2] where the first biosimilar was approved in 2015 [2], representing almost 90% of the world market. Today, more and more biosimilars are entering the healthcare system and there remains the need for broader sharing of information and regular discussions to clarify and alleviate the concerns over biosimilars use for physicians and patients, specifically on the issues of prescribing practice and biosimilars switching.

Methods

In this online event, held on 29 June 2022, the contributors discussed key elements contributing to the wide uptake of biosimilars in Europe and the US and physicians’ trust in prescribing and switching of biosimilars. Presentations of concrete examples and experiences of challenges and uptake policies of biosimilars in Europe, and the current status of market access and successful uptake measures implemented for biosimilars in the US, were given. These allow evaluation of the role of healthcare providers (physicians, pharmacists) and health policymakers in biosimilars use.

The webinar was moderated by Steven Stranne, JD, MD, and partner at Foley Hoag LLP, who has a unique perspective as a physician and lawyer. The Keynote Presentation, ‘Impact of biosimilars in the US healthcare system and the path forward’, was given by the Honourable Eric David Hargan, JD, former United States Deputy Secretary of Health and Human Services (HHS). Additional presentations were given by Mr Michael S Reilly, Esq, Executive Director of ASBM; Dr Ralph McKibbin, past President of the Pennsylvania Society of Gastroenterology and the Society of Gastroenterology and Digestive Disease; Professor Philip J Schneider, Professor at Ohio State University College of Pharmacy; Mr Chad Pettit, Executive Director of Marketing, Biosimilars Business Unit at Amgen; and Mr Andrew Spiegel, Esq, Executive Director of the Global Colon Cancer Association.

Overall, the panel was made up of an academic clinician with specialty in gastroenterology, a pharmacist, a patient advocate, and a market access expert. They shared their experiences with biosimilars, highlighting successes and challenges, their perspectives on prescribing and switching of biosimilars and measures to increase biosimilar adoption, including the role of healthcare providers.

Learning objectives

The overall learning objectives of the webinar were outlined as follows:

- To gain an insight on key elements contributing to the wide uptake of biosimilars in Europe and the US

- To hear about physicians’ trust in prescribing and switching of biosimilars

- To understand the challenges and uptake policies of biosimilars in Europe

- To examine the current status of market access of and successful uptake measures implemented for biosimilars in the US

- To recognize patients’ concerns in biosimilars use

- To evaluate the role of healthcare providers (physicians, pharmacists) and health policymakers in biosimilars use

- To identify educational needs to enhance knowledge on biosimilars use

Registrant statistics

- 244 (speakers included) registered for the SafeBiologics/GaBI webinar on Key factors for successful uptake of biosimilars: Europe and the US

- No. of countries registered/attended: 59/41

- Top 10 countries represented 71% of the total registrants

- Attendance rate at 43% (average webinar attendance rate: 40%)

- Areas of interests, e.g. government, patient: 21

Results

Expert speaker presentations

There were a number of expert speaker presentations followed by a Q&A and an in-depth panel discussion. The presentations are available online [3].

The webinar was opened by Mr Reilly with input from the moderator, Dr Steven Stranne.

Keynote presentation: Impact of biosimilars in the US healthcare system and the path forward

Mr Eric Hargan started by asking the question, ‘Why is increasing biosimilar uptake important?’. He then described how a large proportion of US drug spending is due to biological medicines and this has increased over time as a percentage. As such, the US HHS, keeps a close eye on spending growth due to biologicals and biosimilars. The savings that biosimilars could offer to healthcare systems are of particular relevance. It is also thought that overall, more biosimilars will lead to more savings.

The savings due to biosimilars are estimated to be US$38.4 billion or 5.9% of projected total US spending on biologicals from 2021 to 2025, according to a study published in the American Journal of Managed Care [4]. In addition, more aggressive biosimilar uptake and competition could trigger larger cuts, with savings estimated to be as large as US$124.5 billion from 2021 to 2025 under the most-optimistic scenario. The study also estimates that most of the expected savings from biosimilars would be caused by downward pressure on the brand-name biologicals they compete with, rather than lower biosimilar prices.

Learning from Europe

It was also noted that Europe is widely considered the world leader in the approval and commercialization of biosimilars; and is ahead of the US regarding their regulation, introduction and adoption.

In the European Union (EU), a legal framework for approving biosimilars was established in 2003 [1]. This framework means that biosimilars can only be approved centrally via the European Medicines Agency (EMA) and not nationally [5]. EMA first developed guidelines for the approval of biosimilars via an abbreviated registration process during 2005 to 2006 [6]. Omnitrope (somatropin) was the first product approved in the EU as a biosimilar in 2006 [7] and the first biosimilar monoclonal antibodies (Remsima, Inflectra; both for infliximab) were approved in 2013 [8].

To date, EMA has recommended the approval of 88 biosimilars (including several different marketing authorizations of the same molecule) within the product classes of:

- human growth hormone

- granulocyte colony-stimulating factor

- erythropoiesis stimulating agent

- insulin

- follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH)

- parathyroid hormone

- tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-inhibitor

- monoclonal antibodies.

However, 16 of these have been withdrawn leaving 72 biosimilars approved in Europe at the time of the webinar.

Although the US has lagged behind Europe and did not have the regulatory pathway established until much later, it is now catching up and approved 28 biosimilars in the first five years (vs 11 approved by EMA in the first five years) [1, 2, 9].

US biosimilar approvals

FDA approved its first biosimilar in March 2015 [2]. As of approximately 12 years after implementation of the biosimilar approval pathway, 36 biosimilars have been approved by FDA, with most of those approvals granted in the last three years. Of these, more than 20 are currently on the market and available to patients. Mr Hargan noted that many of the products approved as biosimilars in Europe are approved in the US as ‘follow-on biologicals’ via the earlier, 505(b)(2) pathway, e.g. somatropin, insulin, teriparatide. These medicines are available to US patients but are not considered biosimilars.

In the US, biosimilars have gained a significant share in the majority of therapeutic areas in which they have been introduced (see Figure 1): 80% for filgrastim biosimilars, 70% for trastuzumab and bevacizumab biosimilars, and 55% for rituximab biosimilars. However, infliximab biosimilars have had the most limited adoption, with approximately 20% market share.

Furthermore, variations in uptake rates between the US and Europe are influenced by government involvement, reimbursement structures and tender procurement policies.

Savings in the US

Biosimilars are now generating substantial savings in the US. Mr Hargan highlighted that generally, biosimilars launch at wholesale acquisition cost (WAC) 15% to 37% lower than their reference products and up to 40% below the reference product’s average sales price (ASP). As more become available, the increased competition has been shown to drive down prices of both biosimilars and innovator biologicals.

In 2019, biosimilars saved the US healthcare system US$2.5 billion and in 2020, that figure more than tripled to US$7.9 Billion.

It was highlighted that price was key when it came to boosting biosimilars uptake in the US. As is the case in Europe, as more and more biosimilars launch in a given product class, competition drives prices downward, discounts increase, and biosimilar market share in the US goes up. For example:

- The first US filgrastim biosimilar launched with 15% discount over its reference product. Today, with increased competition, its discount has increased to 35% and it has now attained a majority market share (55%).

- The first US rituximab biosimilar launched at a 10% discount over its reference product. A few months later the second rituximab biosimilar launched at a larger, 24% discount to compete.

As it becomes routine to have 3, 4, or 5 biosimilars approved for a reference product, it is expected that this trend, and savings, will continue.

The future for US biosimilars – interchangeable biosimilars

Mr Hargan concluded by noting that six adalimumab biosimilars have been approved, including one ‘interchangeable’ biosimilar (meaning it can be substituted at the pharmacy level without physician involvement) [10].

An interchangeable biosimilar is a US-specific higher regulatory standard that requires more data and usually includes switching studies.

An interchangeable biosimilar:

1) Must be a biosimilar (‘highly similar’ to reference product).

2) Must have same clinical result expected as with reference product.

3) Must create no additional risk to patient when switching back and forth between itself and reference product.

4) May be substituted for the reference product in a pharmacy without the intervention of the prescriber.

The interchangeable biosimilar, Cyltezo (adalimumab-adbm), will become available in 2023 after the originator product’s patent protection expires. Together with (insulin glargine-yfgn) that was approved as an interchangeable biosimilar in July 2022, these are the first two interchangeable, patient-administered biosimilars in the pharmacy side and not infused in a clinical setting. It is anticipated that this increased competition will lead to continued savings. Mr Hargan highlighted that this will also be a test of to what degree an ‘interchangeable’ designation affects physician prescribing and formulary design of payers. He noted that, in terms of this there are potential for reimbursement and regulatory changes, and asked, ‘Will all products compete on a level playing field?’

European prescribers trust in prescribing and switching biosimilars

Mr Michael Reilly outlined how the ASBM has carried out a number of prescriber surveys across the globe between 2012?2022 [11-16].

As was highlighted by Mr Hargan, Mr Reilly also noted that Europe is widely acknowledged as a global leader in biosimilars for successfully developing a robust and sustainable biosimilars programme. To understand Europe’s success, it is critical to understand that European physicians are generally in power to prescribe in the best interest for patients.

Mr Reilly outlined the findings of the 2019 European prescribers survey [11] which was a refresher of that carried out in 2013 [14].

The 2019 survey revealed that European physicians increased their familiarity between 2013 and 2019 and, after 13 years of experience with biosimilars in Europe, physicians:

- Increasingly consider that they should maintain control of treatment decisions as highly important.

- Are more than twice as uncomfortable switching a stable patient to a biosimilar than they are prescribing a biosimilar to a treatment-naïve patient.

- Remain uncomfortable with switching a patient to a biosimilar for non-medical reasons.

- Are highly uncomfortable with a non-medical substitution performed by a third party. This figure has increased sharply since the 2013 survey.

- Consider it highly important for governments to make multiple therapeutic choices available in tenders; and believe these tenders should take into account factors besides price.

Overall, as familiarity and comfort with biosimilars increased, so did the importance to physicians of maintaining control of treatment decision.

Online questions

Q1: It is good to see how penetration rates are consistently high in various geographies. What about variances in time it takes to reach such penetration levels?

A1 (Reilly): The results of the surveys would suggest that involving physicians and patents when developing policies that have an impact on treatment decisions is critical. It is also important for these policies to provide the flexibility to meet individual patient needs that can sometimes be different from patient to patient. The extent to which these issues are considered play an important role in penetration levels for biosimilars.

Q2: There are some widely anticipated biosimilars expected to hit the market in 2023, what do you think will be the impact of those, if any?

A2 (Reilly): More biosimilars in the marketplace will create more price competition and lower costs for treatment with biological medicines. This has been shown in market research where the more competitors there are, the more prices come down.

US physicians’ perspective in biologicals/biosimilars prescribing and substitution

Dr Ralph McKibbin presented the results of a 2021 ASBM survey of US physicians [17]. The survey examined:

- Knowledge about biologicals and biosimilars/approval process.

- Confidence in biosimilars: their safety and efficacy.

- Substitution and switching: when and how? Who decides? What data should be required?

- Product identification: how best to differentiate between a biological and its various biosimilars?

- Reimbursement policies: which products should be covered and why?

The study revealed that US physicians are:

- very confident in the safety and efficacy of biosimilars

- very comfortable prescribing biosimilars to new patients

- generally comfortable switching a patient to a biosimilar, if they are leading the switch

- not comfortable with third party, non-medical switching.

Overall, the interchangeable designation, makes the majority of physicians more comfortable with prescribing and substitution.

Dr McKibbin also highlighted that, when comparing different surveys from across the globe, there is strong agreement that it is very important or critical that the physician, with the patient, decides which treatment option to use, rather than a third party.

European and US physicians agree that it is very important or critical that payers (public and private) reimburse/cover multiple products, including the originator biological as well as the different biosimilars. They also agree that it is very important or critical that payers (public and private) reimburse/cover multiple products, including the originator biological as well as the different biosimilars.

Regarding the access scenarios, US physicians prefer the approach of Western Europe (where multiple products including innovator and biosimilars are reimbursed, biosimilars may be encouraged for new patients, no automatic substitution permitted) over that of Canadian provinces that have implemented forced substitution (only the government-chosen biosimilar or biosimilars are reimbursed, new patients must be prescribed this product, and current patients must switch).

A comprehensive report of the survey is published in GaBI Journal [17] or the poster with video walkthrough is viewable at www.safebiologics.org.

Online questions

Q1: Considering the 2021 US physicians survey results showing the physicians’ concerns about switching to biosimilars, would they be voluntarily switched to a biosimilar if a patient is being treated with an off-patent originator?

A1 (McKibbin): While we did not specifically ask about off-patent originator medications, in clinical practice they would be viewed as identical to the drug while it was still under patent protection with no change in production mechanisms or testing. The concerns expressed were related to the safety and efficacy of the biosimilar medications.

Q2: What is the clinical importance of some patients’ unawareness/mistrust on biosimilars (in particular in non-medical switching) on adherence/nocebo/other outcomes?

A2 (McKibbin): On the surface this is a simple question but there are so many issues wrapped up in this. While the placebo effect is commonly thought to be related to patients ‘believing they are on treatment’ so there is an improvement in their condition, but there can also be Pavlovian type mechanisms developed from previous experiences. Similarly, the nocebo effect is a recently used ‘buzz word’ which some use to suggest that prescribers are using loaded language to suggest that biosimilars might be less effective thereby resulting in side effects or lack of efficacy. Branding by marketers with direct-to-consumer advertising of originator medicines greatly influences the patients as well. More than six billion dollars are spent yearly on this type of advertising. Industry data shows that as many as 42% of patients will ask for a medication by name. I believe that the advertisers feel this investment will ‘pay off’. If a physician informs a patient that there is a ‘highly similar’ medication which can or will be substituted for condition. Will the patient have the same level of confidence? What if this is a life and death situation such as cancer treatment agents? Marketers have a long history of building brands to inspire confidence. I would suggest, by example, to think of brand name versus generic or store brand frozen vegetables. Do we in our hearts think that they are identical or just similar? Getting patients to be fully confident in biosimilars likely requires looking at all of the forces influencing them.

Sustainable biosimilars market in Europe – policy considerations

In his presentation, Professor Philip Schneider summarized how Europe has the largest biosimilar market in the world (approximately 60% of the global biosimilar market). As of June 2022, 70 biosimilars of 15 originator biological medicines had marketing authorization in Europe. (~50 unique products, under different brands). Here, biosimilar market share is as high as 91% for older products (before the approval of the first monoclonal antibody biosimilar in 2013) and as high as 43% for newer products (approved post-2013). In light of this, European countries, with their large biosimilar markets and diverse healthcare systems, serve as valuable examples of different approaches to biosimilar policy.

He highlighted the findings of the 2020 white paper, ‘Policy recommendations for a sustainable biosimilars market: lessons from Europe’ [18], that had the overall objective to identify principles which can be applied to develop an efficient and sustainable biosimilar market. It examined findings and recommendations of five previous studies and reports on biosimilar sustainability in Europe.

The 2020 white paper revealed that there are differences in biosimilar policy within the 28 EU Member States and the three European Economic Area (EEA) countries, these are:

- Different supply and/or demand-side incentives

- Different degrees of competition

- Determined either at the national, regional or hospital level, or a mixture of these

- Independent of the kind of policy which is pursued, data suggest that biosimilar price and use also depends on therapeutic area and the time the biosimilar has been on the market.

Concerning national tender markets, Norway and Denmark are the only European countries to pursue a national tender policy for biosimilar products, such as adalimumab, etanercept, or infliximab. Denmark will only reimburse the manufacturer with the lowest bidding price for a particular molecule, for a 12-month period. This potentially requires physicians to switch patients every 12 months. In Norway’s tender process the choice is ultimately left to the physician and all lower ranked products are still reimbursed if prescribed, i.e. switching is not explicitly mandated as it is in Denmark. Tenders in Norway tend to be in effect for one year.

It is clear that across all European markets, biosimilars have:

- increased competition

- reduced unit cost of both originator and biosimilars compared to price levels prior to the arrival of biosimilars

- increased volume consumption of molecules with biosimilar competition thus expanding market access and optimizing patient dosing

- alleviated budget pressures by providing headroom to fund novel treatment solutions.

While the policies by which this has been achieved vary between countries, all major European markets share the following principles:

- Automatic substitution for biologicals is forbidden.

- All approved biologicals, i.e. originators and their biosimilars, are available on the market and are reimbursed when prescribed.

- Reimbursement decisions on novel treatment solutions are independent from biosimilar use and uptake.

- The time from market approval to first product sales for biosimilars is shorter than the time to first sales of novel medicines.

The six principles of the ‘Gold Standard’

Professor Schneider noted that there are six principles that support the ‘Gold Standard’ for biosimilars as outlined in the white paper, these are:

1. Policies should be designed to incentivize and reward innovation in all types of biologicals.

2. Healthcare financing must take into account societal benefits derived from biological medicines, as well as the unique characteristics of biologicals.

3. Procurement practices must provide for multiple suppliers and a minimum term of 12 months.

4. Physicians must have autonomy to choose the most appropriate medicine for their patient, including making decisions on switching, which must also be consented to by the patient; no automatic substitution.

5. Mandatory brand-name prescribing to avoid unintended switches and a robust pharmacovigilance system to report adverse drug reactions (ADRs).

6. Policies with potential to undermine sustainability, such as measures which induce biosimilar uptake or promote preferential treatment, thereby limiting physician choice, should be avoided.

The white paper identified three must-have principles:

1. Physicians should have the freedom to choose between off-patent originator biologicals and available biosimilars and to act in the best interest of their patients based on scientific evidence and clinical experience.

2. Tenders should be designed to include multiple value-based criteria beyond price, e.g. education, services, available dose strengths, and provide a sufficient broad choice (multi-winner tenders versus single-winner tenders) to ensure continuity of supply and healthy competition.

3. A level playing field between all participating manufacturers is the best way to foster competition; mandatory discounts which place artificial downward pressure on manufacturers do not engender a sustainable market environment.

Professor Schneider concluded that while countries seek to replicate Europe’s success with biosimilars, some are ignoring the principles which made it possible. For example, there are forced-switching policies enacted in both Canada and Australia.

Forced switching in Canada

Some Canadian provinces (Alberta, British Columbia, Quebec and New Brunswick, have begun to forcibly switch patients to the government-chosen biosimilar.

Forced switching in Australia

The Australian government has also force-switched patients, including stage IV cancer patients. Reimbursement practices have caused manufacturers to cancel planned launches and even remove their products from the country.

In addition to raising concerns among patients and physicians, these forced-switching policies may jeopardize the long-term sustainability of these countries’ biosimilar markets.

Online questions

Q1: Do you consider approval with only Quality/CMC [chemistry, manufacturing, and controls] and PK [pharmacokinetics] comparability as ‘lower standard’?

A1 (Schneider): The scientists tell us analytics are more sensitive than clinical studies in detecting differences in similar biological molecules, so they might answer this question. Having the real-world experience demonstrated by clinical trials would make most healthcare professionals and patients more comfortable and confident in biologicals may be affected by reducing or even eliminating these studies. This issue places increased importance on post-marketing surveillance programmes and pharmacovigilance, which is why ASBM has been such a strong supporter of distinguishable names for biological medicines.

Q2: It is very informative to see physician’s reactions to various dynamics including specific points of discomfort. How does this discomfort affect actual uptake of the biosimilar if it’s driven for example by a payer’s formulary design?

A2 (Schneider): The experience in Australia where the Pharmaceutical Benefits Advisory Committee mandated switching to a biosimilar resulted in significant pushback from physician and patient groups and significantly slowed the adoption of the biosimilar. Physicians and patients need to be part of the policymaking process when it comes to those that affect individual patient care decisions.

Measures leading to successful uptake and the current state of market access of biosimilars in the US

Mr Chad Pettit described how Amgen is developing its biosimilars portfolio in the therapeutic areas of oncology, haematology and chronic inflammatory diseases. The company currently (at time of writing) has 11 biosimilar candidates in its portfolio, including some approved and marketed biosimilars.

He highlighted that there are four elements that are crucial for fostering a robust and sustainable marketplace for biosimilars:

- Stakeholder confidence requires scientifically appropriate regulatory standards.

- A marketplace that encourages competition allows for meaningful savings and long-term sustainability.

- Scientifically accurate educational outreach supports market success.

- A successful marketplace requires a foundation of intellectual property.

The US biosimilar marketplace is now well established and accelerating across many therapeutic areas. At the time of the webinar there were 36 approved and 21 launched biosimilars on the US market.

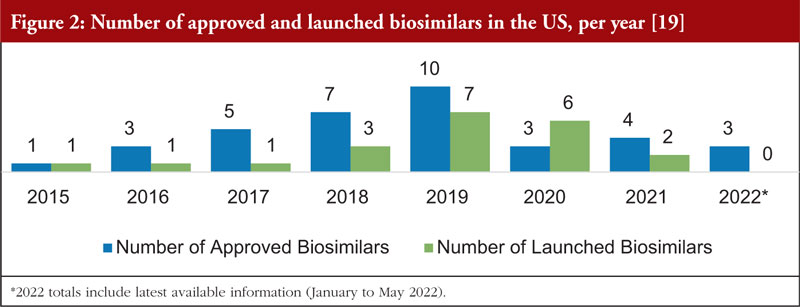

Figure 2 shows the number of biosimilars approved and launched each year from 2015 to 2022. There was a dramatic increase in biosimilar launches from 2018 to 2020 compared to prior years.

The slowdown of biosimilar approvals in 2020 and 2021 observed in Figure 2 was likely due to several factors, some of which were pandemic related. Over the next few years, the US marketplace with biosimilars should recover from this decline in activity, with new approvals and launches expected to increase at pre-2020 rates. Despite the decline in the number of approvals during the 2020 to 2021 timeframe, the number of development programmes that are participating in the FDA Biosimilar Development Program has continued to rise, with 77 in March 2019, 79 in March 2020, 90 in March 2021 and 97 in December 2021.

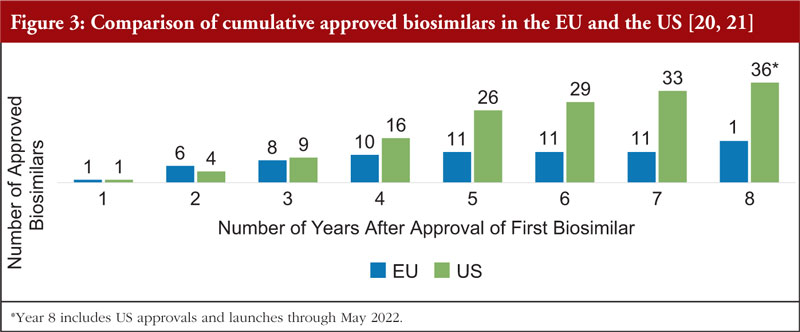

Mr Pettit also pointed out that biosimilars in the US market is advancing at a faster rate than the EU market during a comparable time period. In the eight years after the EU approved the first biosimilar (2006), there were 15 approved biosimilars. By contrast, in the eight years after the US approved the first biosimilar (2015), there were 36 approved biosimilars, see Figure 3.

Figure 3 shows the cumulative number of biosimilars approved in the EU versus the US, beginning with the year the first biosimilar was approved. The slowdown in EU approvals between years 4 and 7 was likely due to several factors that may include intellectual property timelines and duration of development programmes.

In addition, biosimilars are helping reduce healthcare costs in the US by providing significant wholesale acquisition cost (WAC) and average sales price (ASP) savings at launch and through price competition, resulting in the opportunity for additional savings over time.

As shown in Figure 4, manufacturers are launching biosimilars at a WAC that is generally lower than that of the reference product (biosimilars’ ASP becomes available two full quarters after launch):

- Biosimilar WAC versus reference product ASP: almost all biosimilars have launched at a WAC of 3% to 24% below the reference product ASP.

- Biosimilar WAC versus reference product WAC: biosimilars have launched at a WAC that is generally 15% to 37% lower than that of the reference product.

As expected, competition usually results in lower ASP for both reference products and biosimilars, leading to additional savings. Figure 5 shows that, in most cases, the prices of biosimilars declined once ASP was established and continued a steady downward trend. The ASPs for reference products have been declining over time, leading to further opportunity for healthcare savings. It also shows that the prices of biosimilars are decreasing at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 9% to 22% and the prices of most reference products are decreasing at a CAGR of 4% to 20%.

The rate of biosimilar uptake is generally increasing over time, as depicted in Figure 6. Biosimilars have gained significant share in the majority of therapeutic areas where they have been introduced. Additionally, first-to-launch biosimilars have tended to capture a greater portion of the segment compared to later entrants. For therapeutic areas with biosimilars launched in the last three years, the average share was 74%. For therapeutic areas with biosimilars launched prior to 2019, the average share after three years was 38%.

Biosimilar competition is contributing to decreased spending

Mr Pettit also shared Figure 7 which shows the estimated decrease in total drug spend after biosimilar competition was introduced. The change in drug spend shown is the difference between the projected reference product spend (based on historical trend) versus the actual spend following biosimilar launch. Beginning in Q1 2019, drug spending for most classes continues to decrease. The cumulative savings in drug spend for classes with biosimilar competition is estimated to have been US$18 billion over the past six years. Trends show an increase in savings per quarter, and in Q1 2022 alone, savings in drug spend are estimated to be US$3 billion.

The future for biosimilars

Over the next few years, the growing number of biosimilars will likely lead to a rapid evolution in the US biosimilars marketplace, including:

- Expansion of biosimilars into pharmacy benefit reimbursement

- Biosimilars in more therapeutic areas (autoimmune, oncology, endocrinology)

- Approval of additional interchangeable biosimilars in the US

- Focus on provider education and comfort with prescribing and using biosimilars

- Use of real-world evidence to inform the future of the marketplace

These changes are likely to cement the role of biosimilars as viable and integral US treatment options. Biosimilars will find new audiences in different prescriber specialties, pharmacists, payers, and patients, and may change the patient support programme landscape and interactions at the pharmacy counter.

Patients’ perspective on biosimilars use – Europe and the US

Mr Andrew Spiegel gave an overview of patients and biological medicines, describing how over one billion patients around the world have benefited from a biological medicine.

Overall, this has led to improved outcomes for colorectal cancer (CRC) patients. Biosimilars offer patients new treatment choice and reduced costs.

The patient community is excited about biosimilars, but it is key to ensure that biosimilar policies work for patients, which means, it is key to maintain:

- high approval standards – same safety and efficacy as originator products

- control over patient’s treatment

- transparency when used and when switched.

There are concerns over loss of treatment stability due to unnecessary switching. Specifically, patients on biological therapies generally have, for example, chronic diseases; and thus, changes in treatment can have a significant impact. Many patients take years to find a medicine that works for them to help control disease, and in many cases, biological medicines may be the most or even the only effective treatment. As such, for patients that are on a biological that is working for them, decisions related to switching therapy should be carefully considered. Changes in therapy could lead to an immune response and/or a loss of response to the new and old therapy, exposing patients to a scenario with no, or fewer, or more serious treatment options.

Biosimilars training programmes

In light of this, Mr Spiegel highlighted that, in order to facilitate uptake of biosimilars, and switching where this is an option, education is key. He noted that biosimilars training programmes for patient advocacy groups can play an important role here.

He gave an overview of the Global Colon Cancer Association Biosimilars Training Program [25], which was a 6-hour interactive training programme for patient advocacy organizations and advocates representing all diseases to fill a gap in education and awareness. It included:

- 18 videos covering education, key policy issues, and how to take action

- Live chat during presentations

- Breakout discussion and networking rooms

- Speakers include biosimilar thought leaders including medical professionals, patient advocates, policy experts

- Biosimilars Patient Advocacy Toolkit with fact sheets, position statements, sample letters, tips on bringing the patient voice to biosimilar policy

- Training available (no cost) on-demand at LearnBiosimilars.org

During the biosimilar training programme, several representatives from patient advocacy organizations in the US, Europe, Canada and Australia shared the experiences of patients in their countries. It was clear that these experiences varied significantly:

- Patients in Europe seemed the most positive about how biosimilars are being used in their countries.

- Patients in the US also seemed generally positive.

- Patients in Canada, where forced switching is taking root, had somewhat negative assessments.

- Patients in Australia had highly negative recent experiences.

For Europe, patient advocacy representatives, Charis Girvalaki, European Cancer Patient Coalition and Zorana Maravic, Digestive Cancers Europe, described how European governments generally permit the physician to choose the most appropriate biological medicine, between the originator and several biosimilars and that all products will be reimbursed. Generally, lower cost medicines, usually biosimilars, are encouraged for new patients, and some quotas are in place to encourage this. Discussions about switching are made collaboratively and education of patients to build trust in biosimilars has been a priority. In addition, savings attributed to biosimilars are being visibly reinvested into the system, e.g. more healthcare workers.

For the US, the patient advocacy representatives were Mr Spiegel himself and Ms Anna Hyde, Arthritis Foundation. They explained that biosimilars are attaining significant market share, and competition is creating savings. Overall, physician and patient confidence in biosimilars is high, although there are concerns about non-medical switching by third parties (such as private health insurers or pharmacy benefit managers). Substitution laws at the state level, supported by patients, have attempted to address these concerns. Only ‘interchangeable’ biosimilars can be automatically substituted at the pharmacy level. In addition, State law also ensures that the prescribing physician is aware of any substitution that occurs. Many states are working on legislation to restrict how and how often patients may be switched by private insurers, e.g. step therapy.

For Canada, the patient advocacy representative was Ms Gail Attara, Gastrointestinal Society. She advised that four provinces have adopted forced-switching policies: British Columbia (BC), Alberta, Quebec, and New Brunswick. Within this, BC’s policy was the most strict–no exceptions and Alberta offered minimal exceptions, for children and pregnant women. The patient communities, particularly the gastrointestinal (GI) community, joined by their physicians, pushed back heavily on these policies to no avail. Surveys by patient organizations showed many problems including side effects, and many patients discontinuing treatment altogether. The patient community was able to gain some concessions in negotiations with the Quebec government, including many exceptions for age, pregnancy, high-risk patients, mental health, geographical and logistical concerns, e.g. change in infusion clinic location.

For Australia, the patient advocacy representative was Ms Julien Wiggins, Bowel Cancer Australia. In 2015, Australia broke with other advanced nations and allowed automatic substitution of biosimilars, over the objection of patients and physicians. Physicians often blocked these forced substitutions, leading to very low uptake/market share. Several manufacturers have pulled their products – one for liability reasons, after the government began automatic substitution, another after an unexpected, deeper-than normal price cut. Forced switching is now occurring with stage IV cancer patients and there is no grandfathering of current patients. Overall, patients are disappointed and bitter as biosimilars were sold to patients to expand choice, with many products listed alongside each other to choose from – this has not happened. Patients ask the question, ‘They have replaced one monopoly with another … was this by design?’

Mr Spiegel concluded with the following summary:

- Patients support biosimilars but want the policies to work for patients – especially with regard to substitution/switching policies.

- Patient have generally expressed strong satisfaction with the ‘European’ approach: making biosimilars available to patients and achieving savings for their systems through competition without sacrificing patient/physician choice.

- U.S. patients are also optimistic about biosimilars, have been successful in controlling automatic substitution of non-interchangeables, and are working to limit non-medical switching.

- The experiences of Canadian and Australian patients should serve as a warning to patients worldwide about the dangers of governments prioritizing short-term savings over long-term sustainability – and eroding patient trust in biosimilars.

- Education of patients about these issues and experiences is critical, so that we may see more success stories, and fewer horror stories, as biosimilars continue to become available worldwide.

Online questions

Q1: Please clarify the patients’ nocebo effect and how can the biosimilars marketplace achieve the best outcomes for patients and cost savings for the healthcare system?

A1 (Spiegel): These two questions are interrelated. It is an issue of building confidence in order to drive uptake, price competition, and savings. The nocebo effect is when a patient experiences a negative response to a medication due to the expectation of a negative outcome, for example, they might believe the medicine is of lower quality, and thus might not work well for them. It becomes something of a self-fufilling prophecy. This is similar to the better-known placebo effect – wherein a patient is likely to report a positive experience after being conditioned to expect a positive outcome – even if the so-called ‘medicine’ is simply a sugar pill. So how do we build confidence in biosimilars? First, approval standards regarding safety, efficacy, purity, must not be lower for biosimilars than for originator products – or this may create a negative impression of biosimilars as a whole – that they are medicines which could not be approved but for lowered standards. Second, transparency – particularly in substitution – builds patient (and physician) confidence in biosimilars. We want to know which medicine we are being prescribed, and which we receive at the pharmacy or infusion centre. For example, patients have long been supportive of biosimilars having distinct non-proprietary names to clearly distinguish them from the reference biologicals upon which they are based, as well as other biosimilars to that product. Finally, good communication between patients and their healthcare team is essential. Patients want to know (and want their physicians to know) if they receive a biosimilar substitution so that their response to treatment is accurately captured in the patient record and the effects, good or not-so-good, are attributed to the correct product. The patient-physician relationship must remain central in treatment decisions, including if and when to switch between biologicals – as treatment plans are not one-size fits all. Patients trust their physicians and we have seen that while confidence in biosimilars is very high among physicians, there is less acceptance of forced-switching, which should be avoided if patients are to feel they are getting the treatment that is best for them, rather than what is best for the payer. Together, these principles will lead to high confidence and positive expectations for patients about biosimilars, and thus better outcomes.

Summary of panel discussions/Q&A

Following the presentations, the panel members discussed a number of questions. These discussions were moderated by Dr Stranne and are summarized here.

Question 1: Is there a point where the standards imposed on biosimilars should be revisited and loosened to promote more competition?

Mr Hargan was first to address this question and noted that lowering standards to promote competition is not a route currently being considered for biosimilars. He highlighted that biosimilars are a relatively young class of drugs and as such, patient confidence is very important. So, particularly at present, lowering standards is not a good option. He noted, ‘We are starting to see savings due to biosimilars introduction without lowered standards, so lowering them does not seem necessary. Overall, we want more competition, and we are getting it without lowering standards’.

Mr Pettit added that lowering standards will not achieve anything except ‘hurting the system’. The confidence of patients and physicians is needed, and lowering standards will damage this. In addition, lowering standards is unlikely to achieve any additional savings. He noted that, looking at all the different classes of medicines, cost savings in all are fairly consistent once a few biosimilars are introduced. In the future, further savings may be made by investing more in biosimilars in more therapeutic areas. He added, ‘It is not about lowering the bar to get lots of biosimilars in a class, but it is about creating opportunities for investors in many classes of biosimilars’. He also noted that, in the past, regulators had been put under pressure to lower the standards of drugs, e.g. during the AIDs epidemic, but this is not something that was considered then; and should not be now.

Mr Reilly highlighted that there have been many conversations about reducing standards. EMA has argued that this is a moral question as some countries with no access to drugs need access, and perhaps this does require a lowering of standards in some circumstances. However, the ASBM position is: ‘no easy point of access’. This means that, countries with fewer resources should not receive medicines that are substandard compared to those received by wealthier nations. This is in opposition to EMA and WHO’s position. In relation to this, he asked the question, ‘How far do you lower standards before you make a mistake that will undermine confidence?’

Dr McKibbin noted that, from a physician’s perspective, ‘people want confidence in healthcare system and changing access methods is one thing but lowering standards is another which cannot be done.’

Professor Schneider added that currently there is debate on reducing emphasis on clinical trials in favour of analytics. The argument is that analytics are more effective in proving the position of some biosimilars (in proving biosimilarity), than lengthy and expensive clinical trials. He suggested that there is an ongoing debate on whether the elimination of clinical trials lower the regulatory standards for approval of biosimilars.

Mr Spiegel highlighted that the biosimilars bubble is growing and, ‘the last thing we want is to burst that bubble due to a bad experience of a product that has lower standards’. He noted that, in South America, some countries were calling for lower standards and he asked the question, ‘why should you have lower standards because you do not have as much money as other countries such as Canada, Europe and the US?’ Countries with fewer means should not be in receipt of lower standard drugs, this is not just unfair but dangerous. He added that a bad experience anywhere will affect the whole global biosimilars market.

Dr McKibbin added that we need trust in the system and should make any changes in a stepwise fashion.

Mr Reilly concluded that it is surprising that EMA and WHO regulators argue for lower standards in some regions but never within the EU itself. This could be considered a case of ‘not in my back yard’, or nimbyism.

Question 2: What sort of medical education topics, initiatives, are key to help drive physician acceptance of biosimilars use?

Dr McKibbin advised that the cornerstone of acceptance is transparency. This should be present in every step of the process. Physicians have a responsibility to have an informed conversation with patients, and to understand risks and benefits, he added ‘I read the menu and the patient orders’.

It is very important to have all information on a drug, particularly safety data. In terms of generics, in some cases, the medication can be the same, but the binders may be different, and this can cause issues, e.g. with coeliacs. So, physicians need additional information on manufacturing, processing, and pharmacovigilance. We also need to track all aspects, such as where agents are added and look for side effects; and ensure that reporting bad outcomes is reliable.

Overall, transparency is needed at each step, e.g. between the doctor, pharmacists, pharmacy benefit managers.

Mr Reilly highlighted that, at the conception of the ASBM, key to this was data sharing. In the case of Australia where policymakers created a force-switch policy with an opt out option. They did not believe that physicians would take the extra step to mark ‘DISPENSE AS WRITTEN’ (DAW), to prevent switching. However, it became apparent that 98% of physicians were marking DAW as there was an absence of data that would support switching to biosimilars, and they did not have confidence in the switches. He noted that, when described the US’s interchangeable biosimilars concept, many Australian physicians expressed that they would have a different perspective on switching as the interchangeable products have additional data supporting the biosimilars. Overall, where biosimilars only programmes have been pushed, the absence of negative data has often been highlighted, stating, ‘having data out there is key’.

Question 3: Please comment on when is the appropriate time for an emerging market to start working on collecting data on biosimilars and, with your knowledge, how would you roll that out in a region/country that is starting to grapple with this?

Data demonstrating the safe use, including the safe switching, of biosimilars is absolutely paramount to building physician and patient confidence, and thus, to building a successful biosimilar market from the very beginning stages. We have seen this time and again with physicians we have surveyed across the globe. For example, when asked if switching studies should be conducted before biosimilar substitution should be permitted, overwhelming majorities of physicians in Canada (82%) and Australia (81%) agreed. Physician societies in these countries – including the Canadian Gastroenterological Association (CGA) and Australian Rheumatology Association (ARA) – have repeatedly echoed these views in their own policy statements.

Recent US survey data show that the benefits of data are not merely theoretical. The FDA’s additional data requirements for a biosimilar to be classified ‘interchangeable’, i.e. automatically substitutable at a US pharmacy, make the majority of physicians (57%) more likely to prescribe the biosimilar. Further, it makes the majority (59%) more comfortable with a third-party biosimilar substitution in place of the prescribed reference product.

Too often, however, policymakers confuse or conflate the mere absence of negative data with what physicians really want – the presence of positive data. It is also important that the right data be gathered. Generally speaking, physicians have expressed a desire for robust clinical studies and greater post-marketing surveillance to demonstrate there has been no loss of efficacy or additional adverse events due to switching. Policymakers, however, especially in countries which artificially try to boost biosimilar market share through forced substitution, have either ignored these requests or offered unusual or inappropriate metrics – such as tracking increased hospitalizations. This mismatch has led to biosimilar markets struggling to gain physician support, as we have seen in Canada and Australia, jeopardizing both confidence and long-term sustainability of their markets. Emerging markets should learn from these missteps and support robust data collection about patient outcomes as a key feature of their biosimilar programmes.

Question 4: How does regulatory policy involving biologicals and biosimilars play into the rising concern over potential shortages?

Professor Schneider had just attended an FDA webinar on shortages where a report by an FDA taskforce on drug shortages [26] was shared. This included root causes of drug shortages based on analysis and also made recommendations.

The root causes for drug shortages were:

- A lack of incentives for manufacturers to produce less profitable drugs

- The issue of sustainability of drugs using tendering systems that drive profit out of the system, so that manufacturers leave system, and no one is left to make the drugs needed

- Logistical and regulatory challenges that make it difficult to recover from a disruption

Recommendations included:

- Creating a shared understanding of the impact of drug shortages on patients

- Updating contractual practices to promote sustainable private contracts with payers and purchasing organizations to ensure the reliable supply of medically important drugs

Mr Hargan noted that on the logistical side, in the US, onshoring of medical supplies is likely to increase following the shortcomings highlighted in the pandemic. These were highlighted pre-pandemic but were not acted upon in time which led to shortages. We also now see a paradox where we are more likely to see shortages of low-cost drugs.

Mr Pettit added that from a manufacturer’s perspective, they compete on price, plus things such as manufacturing and reliability of supply. In reality, not all manufactures play ‘all keys on the keyboard’. Some policies that tilt the playing field or restrict competition, do not allow for a robust competitive marketplace and these can trigger situations where shortages are more likely, e.g. all or nothing tenders in Europe that make only a single product available. He stressed that manufacturers are all competing and all have different levels of investment in how they manufacture and the way they ensure reliable supply.

Concurrent online Q&A

Due to the nature of the webinar, the audience had the opportunity to ask questions throughout the day, by submitting them online during the presentations and Q&A session.

Question 1: Directed at Mr Reilly, ‘I do not agree that uptake in Canada for filgrastim 93% market share (MS), pegfilgrastim 95% MS, bevacizumab 85% MS, trastuzumab 70% MS, adalimumab just been launch before force switching infliximab was 5% MS only from 2015 to 2020 now more than 50%’.

Mr Reilly responded that the IQVIA presenter ended the presentation by showing a slide of US and EU and referenced Canada. The issue was whether or not forced switch is sustainable and also the degree to which Canada is diametrically opposite from lessons learned from EU and the US. I would welcome any feedback and data that you would like to share, particularly at the upcoming webinar that will focus on non-medical switching.

Question 2: Following Professor Schneider’s presentation clarification was requested about the Canada policy and forced switching

Professor Schneider responded that focus on Canada’s policy has been on the forced switch aspect of it which takes the physician out of the equation. IQVIA recently presented data in another webinar showing that Canada is doing poorly on uptake relative to the US and EU even with a forced switch approach. This was also a lesson learned from Australia when they began with a forced switch approach but allowed the physician to write DAW [Dispense as Written], wherein they defaulted to DAW. Canada is open to multi-biosimilar switching not to just one biosimilar.

Question 3: Following Dr McKibbin’s presentation it was noted that the surveys are not based on the same period of time (2016 and 2017 Canada, to 2021 comparing different countries). In the short lifetime of a biosimilar this is a huge timeframe, how is this reflected in the results?

Dr McKibbin acknowledged that the surveys were conducted over a range of time and work has constantly been done to update these. The US survey was redone in 2021, the EU in 2019 and we are just updating Canada now. We only compare them to demonstrate clear trends.

Question 4: Directed at Mr Reilly, do you have some surveys in Norway and Denmark where the system is different versus major other markets?

Mr Reilly responded that the EU surveys were over the five western EU countries (Spain, Italy, UK, France and Germany) with the most recent survey including Switzerland. We are certainly open to surveying those countries but there is a significant cost for these surveys. Do you believe that it would provide useful information and worth doing?

Concerning the question of ‘If we are looking to Europe as a model of biosimilar adoption and use, what are the opinions in regard to animal toxicology studies, extensive phase III studies, interchangeability studies which are either not performed or performed on a more efficient and expedited fashion in Europe?’ This topic will be dealt with in an upcoming webinar.

Conclusions

The webinar provided the opportunity to gain insight on key elements contributing to the wide uptake of biosimilars in Europe and the US. Surveys were presented that described the physicians’ trust in prescribing and switching of biosimilars. The challenges and uptake policies of biosimilars in Europe were outlined, and the status of market access of and successful uptake measures implemented for biosimilars in the US was explored. In addition, the webinar highlighted issues in regions such as Canada and Australia, where forced-switching policies have been introduced. The webinar also provided the opportunity to evaluate the role of healthcare providers (physicians, pharmacists) and health policymakers in biosimilars use, and identify educational needs to enhance knowledge on biosimilars use globally.

Acknowledgement

The Generics and Biosimilars Initiative (GaBI) wishes to thank all speakers and moderator in delivering the presentations, implementing the panel discussion and clarifying information when finalizing the meeting report, as well as Mr Michael S Reilly for his strong support through the offering of advice and information during the preparation of the webinar.

The authors would like to acknowledge the help of the webinar speaker faculty and all participants, each of whom contributed to the success of the webinar and the content of this report, as well as the support of the moderator in facilitating meaningful discussion during the panel discussions, and contributing to the finalization of this meeting report.

Lastly, the authors wish to thank Ms Alice Rolandini Jensen, GaBI JournalEditor, in preparing and finalizing this meeting report manuscript.

Speaker Faculty and Moderator

Speakers

The Honourable Eric D Hargan, JD

Ralph McKibbin, MD, FACP, FACG, AGAF

Chad Pettit, MBA

Michael S Reilly, Esq

Professor Philip J Schneider, MS, FASHP, FASPEN, FFIP

Andrew Spiegel, Esq

Moderator

Steven Stranne, MD, JD

Editor’s comment

Speakers and moderator had provided feedback on the article content and panel discussion, read and commented the revised content of the manuscript, and approved the final report for publication.

Competing interests: The webinar was funded by ASBM.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Authors

Michael S Reilly, Esq

Professor Philip J Schneider, MS, FASHP, FASPEN, FFIP

References

1. GaBI Online – Generics and Biosimilars Initiative. Biosimilars approved in Europe [www.gabionline.net]. Mol, Belgium: Pro Pharma Communications International; [cited 2022 Sep 16]. Available from: www.gabionline.net/biosimilars/general/biosimilars-approved-in-europe

2. GaBI Online – Generics and Biosimilars Initiative. Biosimilars approved in the US [www.gabionline.net. Mol, Belgium: Pro Pharma Communications International; [cited 2022 Sep 16]. Available from: www.gabionline.net/biosimilars/general/biosimilars-approved-in-the-us

3. Key factors for successful uptake of biosimilars: Europe and the US [webinar]. Alliance For Safe Biologic Medicines (ASBM) and Generics and Biosimilars Initiative (GaBI). 29 June 2022. Available from: https://gabiworkshop.wixsite.com/asbm1-1

4. Mulcahy A, Buttorff C, Finegold K, El-Kilani Z, Oliver JF, Murphy S, et al. Projected US savings from biosimilars, 2021-2025. Am J Manag Care. 2022;28(7):329-35.

5. European Medicines Agency. Marketing authorisation [homepage on the Internet]. [cited 2022 Sep 16]. Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/human-regulatory/marketing-authorisation

6. GaBI Online – Generics and Biosimilars Initiative. EU guidelines for biosimilars [www.gabionline.net]. Mol, Belgium: Pro Pharma Communications International; [cited 2022 Sep 16]. Available from: www.gabionline.net/guidelines/EU-guidelines-for-biosimilars

7. GaBI Online – Generics and Biosimilars Initiative. Biosimilars use in Europe [www.gabionline.net]. Mol, Belgium: Pro Pharma Communications International; [cited 2022 Sep 16]. Available from: www.gabionline.net/Reports/Biosimilars-use-in-Europe

8. GaBI Online – Generics and Biosimilars Initiative. EMA approves first monoclonal antibody biosimilar [www.gabionline.net]. Mol, Belgium: Pro Pharma Communications International; [cited 2022 Sep 16]. Available from: www.gabionline.net/biosimilars/news/EMA-approves-first-monoclonal-antibody-biosimilar

9. Generics and Biosimilars Initiative Journal (GaBI Journal). A white paper: US biosimilars market on pace with Europe. 2020;9(4):150-4. doi:10.5639/gabij.2020.0904.025

10. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Considerations in demonstrating interchangeability with a reference product. Guidance for industry. 2019 [homepage on the Internet]. [cited 2022 Sep 16]. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/considerations-demonstrating-interchangeability-reference-productguidance-industry

11. Feldman MA, Reilly MS. European prescribers’ attitudes and beliefs on biologicals prescribing and automatic substitution. Generics and Biosimilars Initiative Journal (GaBI Journal). 2020;9(3):116-24. doi:10.5639/gabij.2020.0903.020

12. Jensen AR. Biosimilar product labels in Europe: what information should they contain? Generics and Biosimilars Initiative Journal (GaBI Journal). 2017;6(1):38-40. doi:10.5639/gabij.2017.0601.008

13. Murby SP, Reilly MS. A survey of Australian prescribers’ views on the naming and substitution of biologicals. Generics and Biosimilars Initiative Journal (GaBI Journal). 2017;6(3):107-13. doi:10.5639/gabij.2017.0603.022

14. Dolinar RO, Reilly MS. Biosimilars naming, label transparency and authority of choice – survey findings among European physicians. Generics and Biosimilars Initiative Journal (GaBI Journal). 2014;3(2):58-62. doi:10.5639/gabij.2014.0302.018.

15. Reilly MS, Gewanter HL. Prescribing practices for biosimilars: questionnaire survey findings from physicians in Argentina, Brazil, Colombia and Mexico. Generics and Biosimilars Initiative Journal (GaBI Journal). 2015;4(4):161-6. doi:10.5639/gabij.2015.0404.036

16. Gewanter HL, Reilly MS. Naming and labelling of biologicals – a survey of US physicians’ perspectives. Generics and Biosimilars Initiative Journal (GaBI Journal). 2017;6(1):7-12. doi:10.5639/gabij.2017.0601.003

17. McKibbin RD, Reilly MS. US prescribers’ attitudes and perceptions about biosimilars. Generics and Biosimilars Initiative Journal (GaBI Journal). 2022;11(3):96-103. doi:10.5639/gabij.2022.1103.016

18. Reilly MS, Schneider PJ. Policy recommendations for a sustainable biosimilars market: lessons from Europe. Generics and Biosimilars Initiative Journal (GaBI Journal). 2020;9(2):76-83. doi:10.5639/gabij.2020.0902.013

19. Xcenda. Biosimilar approval and launch status in US. April 2022 [homepage on the Internet]. [cited 2022 Sep 16]. Available from: https://www.xcenda.com/biosimilars-trends-report

20. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Biosimilar product information. 2022 [homepage on the Internet]. [cited 2022 Sep 16]. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/drugs/biosimilars/biosimilar-product-information

21. European Medicines Agency. Authorised medicines: biosimilar [homepage on the Internet]. [cited 2022 Sep 16]. Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/search_api_aggregation_ema_medicine_types/field_ema_med_biosimilar

22. Data on file, Amgen; Reference Product and Biosimilars – WAC and ASP Price; May 2022

23. Data on file, Amgen; Reference Product and Biosimilar Share Trends; May 2022.

24. Data on file, Amgen; Biosimilars Spend Analysis; May 2022.

25. Global Colon Cancer Association and World Patients Alliance. Biosimilars Training for Patient Advocacy Organizations. Available from: www.learnbiosimilars.org/

26. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Drug shortages. Root causes and potential solutions [homepage on the Internet]. [cited 2022 Sep 16]. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/media/131130/download

|

Author for correspondence: Michael S Reilly, Esq, Executive Director, Alliance for Safe Biologic Medicines, PO Box 3691, Arlington, VA 22203, USA |

Disclosure of Conflict of Interest Statement is available upon request.

Copyright © 2022 Pro Pharma Communications International

Permission granted to reproduce for personal and non-commercial use only. All other reproduction, copy or reprinting of all or part of any ‘Content’ found on this website is strictly prohibited without the prior consent of the publisher. Contact the publisher to obtain permission before redistributing.