First Asia-Pacific educational workshop on non-biological complex drugs (NBCDs), Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 8 October 2013

Published on 2013/11/18

Generics and Biosimilars Initiative Journal (GaBI Journal). 2014;3(1):30-3.

Author byline as per print journal: Professor Philip D Walson, MD, Professor Stefan Mühlebach, PhD, Beat Flühmann, PhD

|

Introduction: In recent years a new category of medicinal products, the non-biological complex drugs (NBCDs) emerged. They are distinct from both the small molecules and the biological therapeutics by being composed of non-homomolecular large structures, some of which may be nanoparticulate, and by not being a biological product or being chemically synthesized. Approval of their follow-on copies is problematic because like biologicals they are impossible to be fully characterized by only their physiochemical properties and both their structure and function are sensitive to small changes in the laborious and difficult to control manufacturing process. Today, requirements for authorization of follow-on NBCDs are unclear and handled on a case-by-case basis. |

Submitted: 20 January 2014; Revised: 31 January 2014; Accepted: 13 Februray 2014; Published online first: 26 February 2014

Introduction

With few exceptions small molecule generic drug products provide equivalent results at lower costs and can be considered as therapeutically equivalent. However, biological follow-on products, i.e. biosimilars, are impossible to completely characterize by their physiochemical properties and even minor changes in their manufacturing processes can result in clinically meaningful differences in efficacy or safety. Therefore, biosimilars are regulated differently than are follow-on small molecule generics using a more extensive similarity approach [1].

Effective, abbreviated regulatory procedures exist for assessing follow-on ‘generic’ versions of small molecule medicinal products. Proof of pharmaceutical equivalence and comparability of bioequivalence establish therapeutic equivalence for such medicinal products (generics paradigm). Macromolecular, biological complex medicinal products however cannot be fully characterized by physicochemical tests. In addition, for many of these medicinal products bioequivalence assessment is either not possible or not indicative of clinical safety and efficacy. Therefore, a different ‘biosimilar’ approach that includes in vitro biological and clinical evaluations has been developed for follow-on biologicals and therapeutic proteins ‘manufactured’ by living organisms.

There are a growing number of non-biological complex drugs (NBCDs) that are neither small molecules nor biologicals. NBCDs include a number of chemically synthesized, macromolecular products such as liposomal products, glatiramoids, and intravenous (IV) iron carbohydrate preparations. As for the biologicals, NBCDs cannot be fully characterized by physicochemical analysis. Even minor changes in their laborious synthetic manufacturing processes can affect composition or structure and result in meaningful differences in clinical effects. Due to their nanosize properties, some of these follow-on versions of NBCDs are also referred to as ‘nanosimilars’. In the past, these ‘nanosimilars’ have been regulated the same as small molecule generics.

The adequacy of this regulatory approval process has been questioned because therapeutic non-equivalence and non-interchangeability of authorized follow-on IV iron sucrose products have been reported [2, 3]. Therefore, authorities addressed the urgent need to define best practices for nanosimilar approval and post-approval pharmacovigilance to maximize the chances that such follow-on products provide patients with non-inferior safety and clinical outcomes [4–9]. Recently, a nanosimilar approval approach has also been proposed [1, 10–12].

Methods

On 8 October 2013, the Generics and Biosimilars Initiative (GaBI) held the First Asia-Pacific Educational Workshop on Non-Biological Complex Drugs (NBCDs) in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. The objectives of the workshop were to raise evidence-based awareness of the potential differences in quality as well as therapeutic and toxic effects of NBCDs including IV iron products. The goal was to promote active discussion amongst various stakeholders from the Asia-Pacific region concerning the best practice methods to approve, regulate, monitor and use follow-on (similar but not identical) NBCDs, and to identify areas of consensus, uncertainty and disagreement concerning these NBCDs best practices.

Speakers were selected by the GaBI Journal publisher and included academicians and regulators from Europe, a practising nephrologist (France) and an obstetrician/gynaecologist (South Korea) who had published research relating to NBCDs and are involved in the day-to-day use of IV iron NBCDs, as well as experts from academia and the manufacturer of the originator iron sucrose product (Venofer®). Non-speaker participants, selected in consultation with the Ministry of Health Malaysia, came from Indonesia, Malaysia, Pakistan, the Philippines, Thailand and Singapore. Prior to the workshop participants were provided a reading list and a questionnaire to complete and return covering current and perceived best practices both of which are available on request to the publisher; as are the questionnaire responses, the reading and participant lists, and copy of all presentations (www.gabi-journal.net/about-gabi/current-activities).

Results

Speakers summarized key aspects of the manufacturing, physicochemical properties, analysis, current regulatory practice and clinical experience with NBCDs.

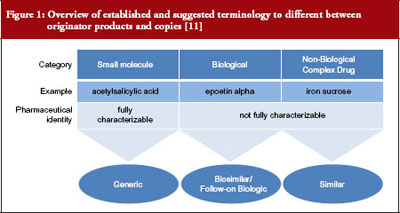

Drug development and regulatory approval require distinct product naming, characterization and use of the specific product in preclinical and clinical evaluation of a product, see Figure 1 [11]. While relatively straight forward for small molecule generics, the required unequivocal identification of the drug product can be impossible for NBCDs and their copies. Regulatory approval of nanosimilars is especially problematic because the understanding of which differences are clinically relevant is very limited. As summarized by Professor Gerrit Borchard, ‘The bio-disposition and activity of NBCDs is determined by their interaction with biological systems. This, in turn, is thought to be governed by their physicochemical parameters, such as size and size distribution, surface charge, and composition. However, a rationale predicting biological outcome based on NBCD properties is still lacking.’ The EU has led the US in development of regulations for biosimilars and nanosimilars and places particular emphasis on proving product efficacy and safety. In 2009, the European Medicines Agency (EMA) implemented the Ad-Hoc Nanomedicine Expert Group, which has published a number of ‘reflection papers’ on approval of NBCD nanomedicines including IV iron sucrose [4–8].

The clinical relevance of follow-on NBCD approval and use was illustrated by two clinical case studies presented by the authors of these published reports. The first was of the substitution of a follow-on iron sucrose product (Ferex, BMI Korea) for the originator (Venofer®, Vifor Pharma Ltd, Switzerland) in gynaecological patients that resulted in significantly more adverse events and higher overall costs [2]. The second was of inferior therapeutic effects and increase in costs seen after substitution of the follow-on Fer Mylan for Venofer® in French renal dialysis patients [3]. Substitutions were both based on theoretical cost savings and the clinicians were not aware of the switch until after they observed the negative effects. These cases raised concerns about both the adequacy of the follow-on NBCD approval processes and the lack of clinician involvement in pharmacy substitution practices. They also suggest that prospective double-blind therapeutic trials should be done to evaluate whether substitutions actually result in cost savings without changes in efficacy or safety. Finally, they illustrate the need for appropriate and indicative post-approval pharmacovigilance studies.

The concerns raised by these cases were mirrored in comments made by participants during the breakout sessions. There was unanimous clinician consensus that treating physicians should be asked or at least made aware before any substitution was made and that there should be adequate post-approval monitoring of such products. The majority of clinicians also felt that such products should be approved only after adequate clinical testing. Regulators indicated that regulatory pathways are being put in place in the Asia-Pacific region but there was consensus that the issues raised by NBCDs were not well understood. Because of their limited regulatory experience with these products regulators and clinicians tend to rely on information supplied by the manufacturers of such products. Follow-on products are generally being regulated as generics on a case-by-case basis. Some post-marketing surveillance procedures are in place, however, their effectiveness was questioned.

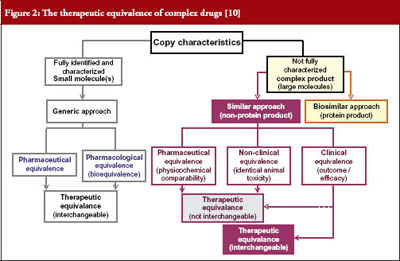

Both clinicians and regulators agreed that the NBCD concept is new and not well understood, therefore, few or no adequate regulatory pathways are in place. In order to develop such pathways, basic scientific and clinical data are needed as well as training and education of all stakeholder groups involved, i.e. patients’ organizations, nurses, pharmacists, clinicians and regulators. Feedback from practitioners to regulatory authorities and interna-tional cooperation of regulatory authorities in Asia-Pacific countries were felt to be important in the development of best practice regulatory approaches but there was general agreement with a previously published proposal, see Figure 2, for approval of NBCD similars [10].

There was consensus that the education of all stakeholders was needed but it was not clear what methods would be the most effective. It was suggested that providing EMA draft opinions to regulators in all countries could lead to greater international regulatory cooperation.

The GaBI Journal will focus on NBCDs in future publications and educational workshops/conferences. The faculty of this workshop was approached to present the topic of NBCD at the upcoming ASEAN ACCSQ PPWG (ASEAN Consultative Committee for Standards and Quality [ACCSQ] Pharmaceutical Product Working Group [PPWG]) Conference to be held on 17–20 June 2014. Also, a session on biosimilars and NBCDs will be held at the FIP meeting in Bangkok, Thailand, in September 2014.

Conclusion

A large and growing number of NBCDs, including IV iron sucrose preparations, are characterized by non-homologous structures, which cannot be fully characterized by physiochemical testing. Rational approval of follow-on versions is problematic because, as with biologicals, even minor changes in production methods can have major but unpredictable impact on their therapeutic profile.

Currently, there is no harmonized and uniform approach in either the EU, the US or the Asia-Pacific region as to how follow-on NBCDs are regulated, used, or monitored after authorization (pharmacovigilance).

Published scientific studies and clinical case reports raise concerns about the adequacy of the methods currently used to approve, use, substitute or monitor follow-on iron sucrose products. Studies suggest that NBCDs require a separate regulatory pathway using a similarity approach that is as, if not even more, stringent than that being used for biosimilars.

There are gaps in the understanding of the properties of NBCDs on the part of regulators, pharmacists, patients, and clinicians that should be addressed by development of guidelines and educational programmes.

Acknowledgements

The Generics and Biosimilars Initiative (GaBI) wishes to thank Ms Arpah Abas, National Pharmaceutical Control Bureau, Ministry of Health Malaysia; and Dato’ Eisah A Rahman , Senior Director Pharmaceutical Services, Pharmaceutical Services Division, Ministry of Health Malaysia, for their strong support of offering advice and information towards the preparation of the educational workshop.

The authors would like to acknowledge the help of all the workshop faculty and participants, each of whom contributed to the success of the workshop and the content of this report as well as the support by Vifor Pharma Ltd who provided unrestricted financial support for the workshop, and review of the draft manuscript.

Disclosure of financial interests: The meeting was sponsored by an unrestricted educational grant to GaBI from Vifor Pharma Ltd.

Professor Stefan Mühlebach and Dr Beat Flühmann are employees of Vifor Pharma Ltd.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Co-authors

Professor Stefan Mühlebach1,2, PhD

Beat Flühmann1,3, PhD

1Steering Committee member, NBCD Working Group, TI Pharma, Leiden, The Netherlands

2Vifor Pharma Ltd, 61 Flughofstrasse, PO Box, CH-8152 Glattbrugg, Switzerland

3Vifor Fresenius Medical Care Renal Pharma Ltd, 37 Rechenstrasse, PO Box, CH-9001 St Gallen, Switzerland

References

1. Mühlebach S, Vulto AG, de Vlieger Jon SB, Weinstein V, Flühmann B,et al. The authorization of non-biological complex drugs (NBCD) follow-on versions: specific regulatory and interchangeability rules ahead? Generics and Biosimilars Initiative Journal (GaBI Journal). 2013;2(4):204-7. doi:10.5639/gabij.2013.0204.054

2. Lee ES, Park BR, Kim JS, Choi GY, Lee JJ, Soon Lee IS. Comparison of adverse event profile of intravenous iron sucrose and iron sucrose similar in postpartum and gynecologic operative patients. Curr Med Res Opin. 2013;29(2):141-7.

3. Rottembourg J, Kadri A, Leonard E, Dansaert A, Lafuma A. Do two intravenous iron sucrose preparations have the same efficacy? Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2011;26(10):3262-7.

4. European Medicines Agency. Reflection paper on the data requirements for intravenous 4 iron-based nano-colloidal products developed with 5 reference to an innovator medicinal product data requirements for IV iron-based nano-colloidal products. EMA/CHMP/SWP/620008/2012. 25 July 2013 [homepage on the Internet]. 2013 Sep [cited 2014 Jan 31]. Available from: http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Scientific_guideline/2013/09/WC500149496.pdf

5. European Medicines Agency. Reflection paper on surface coatings: general issues for consideration regarding parenteral administration of coated nanomedicine products. EMA/325027/2013. 22 May 2013 [homepage on the Internet]. 2013 Aug [cited 2014 Jan 31]. Available from: http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Scientific_guideline/2013/08/WC500147874.pdf

6. European Medicines Agency. Reflection paper on the data requirements for intravenous liposomal products developed with reference to an innovator liposomal product. EMA/CHMP/806058/2009/Rev.02. 21 February 2013 [homepage on the Internet]. 2013 Aug [cited 2014 Jan 31]. Available from: http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Scientific_guideline/2013/03/WC500140351.pdf

7. European Medicines Agency. Joint MHLW/EMA reflection paper on the development of block copolymer micelle medicinal products. EMA/CHMP/13099/2013. 17 January 2013 [homepage on the Internet]. 2013 Jan [cited 2014 Jan 31]. Available from: http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Scientific_guideline/2013/02/WC500138390.pdf

8. European Medicines Agency. Non-clinical studies for generic nanoparticle iron medicinal product application. EMA/CHMP/SWP/100094/2011. 17 March 2011 [homepage on the Internet]. 2011 Apr [cited 2014 Jan 31]. Available from: http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Scientific_guideline/2011/04/WC500105048.pdf

9. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Draft guidance for industry on bioequivalence recommendations for iron sucrose injection; availability. Federal Register. 2013 Nov 6.

10. Schellekens H, Klinger E, Mühlebach S, Brin JF, Storm G, Crommelin DJ. The therapeutic equivalence of complex drugs. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol. 2011;59(1):176-83.

11. Borchard G, Flühmann B, Mühlebach S. Nanoparticle iron medicinal products – Requirements for approval of intended copies of non-biological complex drugs (NBCD) and the importance of clinical comparative studies. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol. 2012;64(2):324-8.

12. Ehmann F, Sakai-Kato K, Duncan R, Hernán Pérez de la Ossa D, Pita R, Vidal JM, et al. Next-generation nanomedicines and nanosimilars: EU regulators’ initiatives relating to the development and evaluation of nanomedicines. Nanomedicine (Lond). 2013;8(5):849-56.

|

Author for correspondence: Professor Philip Walson, MD, Editor-in-Chief, GaBI Journal |

Disclosure of Conflict of Interest Statement is available upon request.

Copyright © 2014 Pro Pharma Communications International

Permission granted to reproduce for personal and non-commercial use only. All other reproduction, copy or reprinting of all or part of any ‘Content’ found on this website is strictly prohibited without the prior consent of the publisher. Contact the publisher to obtain permission before redistributing.