Analysis of Drug Master Files registered in Japan: aiming for a stable supply of active pharmaceutical ingredients

Published on 2018/02/10

Generics and Biosimilars Initiative Journal (GaBI Journal). 2018;7(1):8-13.

|

Introduction/Study objectives: A stable supply of active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) is indispensable for a stable supply of finished pharmaceutical products (FPPs). API manufacturers generally register API information as a Drug Master File (DMF) directly to the Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency (PMDA) in Japan. Because DMFs require appropriate management by their registrants, it is important to clarify the DMF registrants’ distribution. However, despite globalization of the API supply chain, details regarding DMF registration situation in Japan have not been reported. Therefore, we surveyed the status of globalization and characteristics of DMF registrations in Japan. |

Submitted: 26 November 2017; Revised: 23 January 2018; Accepted: 24 January 2018; Published online first: 6 February 2018

Introduction/Study objectives

The national medical care expenditure in Japan increases every year; it amounted to 40.8071 trillion Yen in the fiscal year (FY) 2014, which is more than double the medical care expenditure 25 years ago [1, 2]. The Japanese universal health insurance system ensures that all Japanese citizens receive healthcare services. To protect the system, appropriate management and reduction of medical expenditure are urgently required [3]. One of the measures adopted by the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (MHLW) to address this issue involves promoting the use of generic drugs [4]. In 2007, MHLW published the ‘Action program for the promotion of the safe use of generic drugs’, which raised stable supply, quality assurance, provision of information by generic manufacturers, improvement of the environment for the promotion of use, and matters concerning the medical insurance system [4, 5]. Additionally, MHLW formulated the ‘Roadmap for further promotion of generic medicine use’ in 2013, presenting concrete approaches to promote the use of generic drugs [6]. Moreover, in 2015, the Japanese cabinet decided to increase the market share volume of generic drugs to 80% or more as soon as possible between the FY 2018 and the end of FY 2020 [7].

A stable supply of active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) is indispensable for promoting the use of generic drugs, because API distribution issues can lead to shortage of generic drugs. For instance, of the 46 drug product shortage problems that arose in the FY 2013, 21 were associated with API shortage [8]. These shortages can result in a perception among medical staff and patients that generic drugs are unreliable. Therefore, minimizing the risk of API shortage is crucial for promoting the use of generic drugs.

In applications for marketing authorizations for finished pharmaceutical products (FPPs) in Japan, API quality data including manufacturing methods and controls of APIs need to be submitted to the Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency (PMDA), which is a Japanese regulatory body. Generic drug applicants experience difficulties in obtaining detailed API information, such as manufacturing methods, from an API manufacturer because this information includes large volumes of intellectual property often registered as patents, e.g. synthetic processes, reactions, and purification conditions [9]. To circumvent this issue, applicants can utilize the Drug Master File (DMF) system; this system enables that API information, including confidential intellectual property, is provided by API manufacturers to the PMDA directly, without disclosing protected information to the applicant [10]. The DMF system was introduced in 2005 as a Master File (MF) system in Japan. There are four categories in the MF system: (i) APIs including intermediates; (ii) Excipients, but limited to new excipients and premix excipients with a different composition ratio from the existing ones; (iii) Materials intended solely for use in the manufacture of medical devices (in process); and (iv) Others, e.g. packaging material [10, 11]. MFs classified as APIs, including intermediates, are called DMFs in this manuscript. Similar DMF systems have been individually developed by many regulatory organizations throughout the world [12, 13].

To secure the stable supply of API, appropriate management of DMFs is essential. Recently, API supply chains are being increasingly globalized, and many countries import APIs from foreign manufacturers such as China and India [14–16]. Therefore, it is important to clarify a DMF registrant’s distribution and characteristics on DMF registration. However, details regarding the DMF registration situation in Japan, such as percentage of domestic/foreign DMF registrants, number of DMF registrations by country and region, or number of DMFs for the same API, have not been reported. Therefore, we conducted this survey to clarify the situation of the Japanese DMF registration.

Methods

The source of information was a registration list of MFs as of 31 March 2017 in Japan, which is publicly available as a Microsoft Excel spread sheet. This list is periodically updated on the PMDA website (http://www.pmda.go.jp/review-services/drug-reviews/master-files/0001.html, only in Japanese). The list includes the registration number, initial registration date, registration date of the last change, registration category, trade names of the items, registrant names, and registrant addresses. The list excludes cancelled MFs.

Firstly, we extracted DMFs from the MF list according to the registration category (APIs, excipients, materials and others).

Secondly, we added the registrant country or region in this DMF list based on registrant address. If the address was unclear, we confirmed the country or region using Google Maps. Using this list, we enumerated DMFs by country and region based on the seven continents classification by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan: Africa, Asia, Europe, Latin America and the Caribbean, Middle East, North America, and Pacific [17].

Thirdly, we enumerated registered DMFs for each FY using the initial registration date in the DMF list. The Japanese FY starts on 1 April. Additionally, we surveyed the changes in total DMFs by FY for each of the top five countries.

Furthermore, we surveyed the registration trend for every API. First, we ranked 30 APIs in order of use for FPPs based on the National Health Insurance Drug Price List in Japan, which was updated on 17 March 2017, on the MHLW website (http://www.mhlw.go.jp/topics/2016/04/tp20160401-01.html, only in Japanese). Medical institutions require a stable and continuous supply of the listed FPPs. We excluded FPPs comprising more than two APIs for the purpose of simplification and also, because not all API components are described for some FPPs, e.g. FPPs for peritoneal dialysis. For these 30 APIs, we counted the number of DMFs registered in each API based on the DMF trade name. In consideration of cases where salt and hydrate/anhydrous were not indicated in the DMF trade name, we investigated using the API stem name. For example, ‘amlodipine besilate’ is the official name in Japan, instead, we searched for ‘amlodipine’ in Japanese and English.

Additionally, we enumerated DMFs on the basis of domestic/foreign registrants for each API. We also checked whether each API was listed in the Japanese Pharmacopoeia (JP) 17th Edition, as a reference [18].

Results

1. Number of registered DMFs

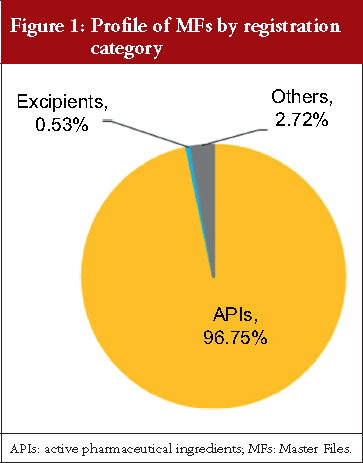

As of 31 March 2017, 3,932 items were registered in the Japanese MF system. Figure 1 shows the percentage of MFs according to the registration category: 96.75% of MFs (3,804 MFs) are categorized as APIs including intermediates, which we call DMFs; 0.53% of MFs (21 MFs) are categorized as excipients limited to new excipients and premix excipients with a new composition ratio; and 2.72% of MFs (107 MFs) are categorized as other items. The last category included various media components and gelatins.

2. Number of DMFs by country or region of registrants

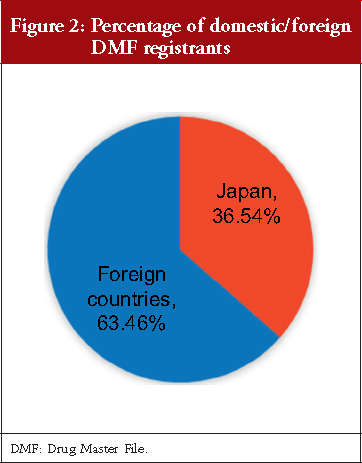

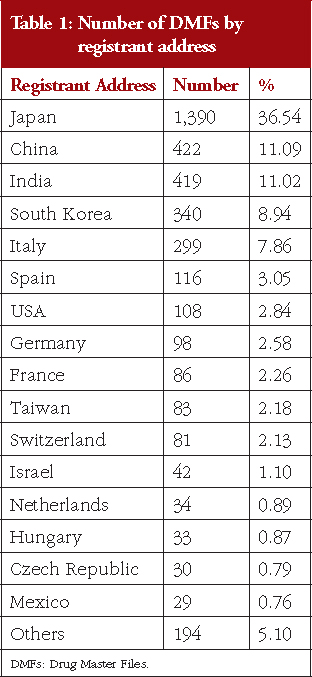

As shown in Figure 2, 36.54% of DMFs (1,390 DMFs) are registered by Japanese registrants, and 63.46% of DMFs (2,414 DMFs) are registered by foreign registrants. DMFs were registered from a total of 46 countries and regions, including Japan. Table 1 shows the number of DMFs by registrant addresses, with 16 having more than 0.50% (19 DMFs) of total DMFs. China and India had registered over 11.00% of the total DMFs, South Korea 8.94%, and Italy 7.86%. Countries and regions geographically close to Japan (China, South Korea and Taiwan) together registered 22.21% of the total DMFs.

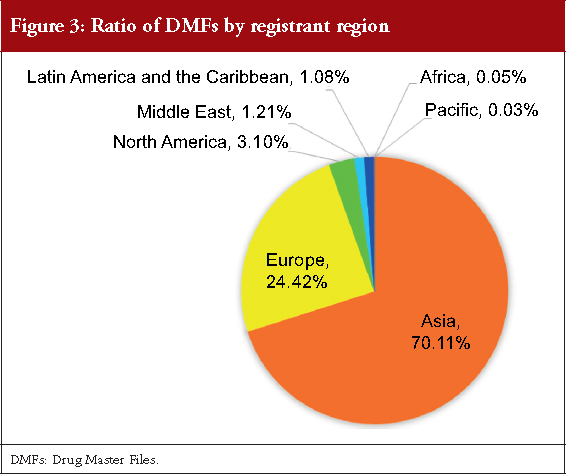

Figure 3 shows the regional distribution of DMF registrants. Among the seven continents, Asia with 70.11% had the highest number of DMFs (2,667 DMFs), followed by Europe with 24.42% (929 DMFs) of total DMFs. DMFs were also registered by North America, Middle East, Latin America and the Caribbean, Africa, and Pacific. Thus, DMFs in Japan are registered from all regions in the world.

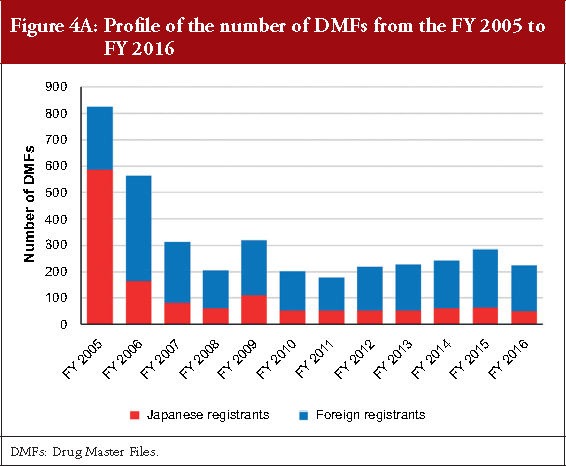

3. Profile of the number of DMFs

Figure 4A shows the profile of the number of DMFs registered from the FY 2005 to the FY 2016. In the first and second FY, the number of registrations was 825 and 563, respectively. After the FY 2007, approximately 200–300 DMFs were registered every FY. Although the percentage of DMFs registered by the Japanese registrants was 71.03% in the FY 2005 when the MF system started, a higher number of DMFs were registered by foreign registrants after the FY 2006. The percentage of DMFs registered by foreign registrants in the FYs 2014, 2015 and 2016 were 74.49%, 77.89% and 77.78%, respectively.

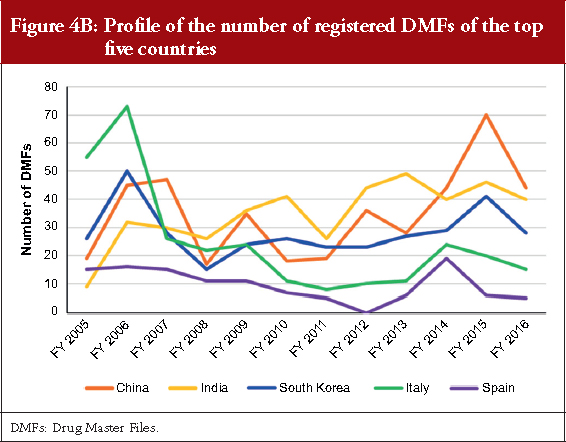

The DMF profiles of the top five foreign countries China, India, South Korea, Italy and Spain from the FY 2005 to the FY 2016 are shown in Figure 4B. Their DMF registrations temporarily increased in the FY 2006, that was the second FY after the MF system was started. The number of DMFs registered from China and India exhibit a trend to increase through a decade. The number of DMFs from South Korea has nearly remained constant despite some fluctuations in each FY, and the number of DMFs from Spain remains roughly similar. In contrast, the number of DMFs from Italy showed a decreasing trend. In the FY 2016, 19.56%, 17.78%, 12.44%, 6.67% and 2.22% of the total DMF registrations were from China, India, South Korea, Italy and Spain, respectively.

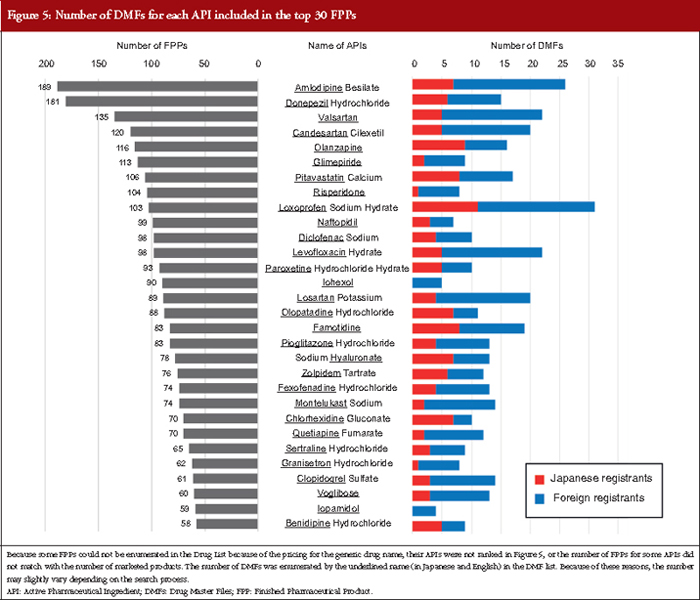

4. Trend of the number of DMFs for the same APIs

Figure 5 shows the number of DMFs of the top 30 APIs included in the highest numbers of FPPs in the Japanese Drug Price List in 17 March 2017. The number of DMFs of APIs with many FPPs was not necessarily high. For these 30 APIs, the average number of DMFs per API was 13.73. The ratio of foreign registrants to total registrants for one API was different for each API. Amlodipine besilate products had the highest number of FPPs in the list, with 189 FPPs of originators and generic drugs including three different strengths and four types of dosage forms: tablets, orally disintegrating tablets, orally disintegrating films, and jellies for oral administration. For these amlodipine besilate products, 26 DMFs that included ‘amlodipine’ in their trade name were registered, and 19 of the 26 DMFs (73.08%) were registered by foreign registrants from India, Slovenia, South Korea, Spain and the US. The largest number of DMFs among these 30 APIs was loxoprofen sodium hydrate, which is a component of 103 FPPs, available in six different strengths and seven types of dosage forms: tablets, granules, oral solutions, cataplasms, tapes, gels, and pump sprays for cutaneous application. For these loxoprofen sodium hydrate products, 31 DMFs that included ‘loxoprofen’ in their trade name were registered, and 20 of the 31 DMFs (64.52%) were registered by foreign registrants from China, South Korea and Taiwan.

Additionally, 27 of the 30 APIs (90.00%) were listed in the JP (17th Edition), although pitavastatin calcium, sodium hyaluronate, and chlorohexidine gluconate did not match exactly with the JP monograph titles, which were pitavastatin calcium hydrate, purified sodium hyaluronate, and chlorhexidine gluconate solution, respectively. In contrast, three APIs, olanzapine, granisetron, and sertraline hydrochloride have not been listed yet. Interestingly, montelukast sodium products, whose API monograph in the JP was developed to harmonize with the European Pharmacopoeia (Ph. Eur.) and the United States Pharmacopeia (USP) monographs as a pilot project for harmonization of API monographs, were ranked in the top 30 APIs [19]. Fourteen DMFs for montelukast sodium were registered from China, India, Ireland, Israel, Japan, South Korea and Spain.

Discussion

In the present study, we surveyed the current situation of the Japanese DMF registration to clarify its characteristics and the status of globalization.

Among the four MF categories, we found that of the 3,932 MFs registered in Japan, almost all MFs were for APIs including intermediates (96.75%; see Figure 1). This result suggests that the MF system introduced in 2005 is a popular tool in Japan to register information of APIs to the PMDA directly. The reason why excipient MFs are hardly registered is that registrations of excipients are limited to new excipients and new premix excipients. Because manufacturing methods of general excipients are not required to be submitted for marketing authorization applications, this limitation is rational in the light of the purpose of the MF system, which is to protect intellectual property of the MF registrant.

Regarding the number and percentage of DMFs registered by country, we found that 36.54% DMFs were registered by domestic manufacturers and 63.46% by foreign manufacturers, see Figure 2. Although the registered DMFs are not necessarily active, this result is consistent with an earlier survey focusing on unit of manufacturing sites based on questionnaire responses from marketing authorization holders, which reported that in the FY 2015, 35.70% FPPs were manufactured with APIs only from domestic sites and that the remaining FPPs used APIs that were partially or entirely manufactured in foreign sites [20]. Our results also show that the major DMF registrations have been from China, India, South Korea, Italy and Spain, and that DMFs have been registered to the PMDA from all the seven continents of the world, see Table 1 and Figure 3. Along with the API supply chain globalization, DMFs are registered in Japan from various countries and regions.

Regarding the profile of the number of DMFs, the registration numbers were high in the first two years because of the revised pharmaceutical law in 2005 that introduced the MF system. After the FY 2007, the number of DMF registrations was constant with approximately 200–300 registrations each year. Two factors may be associated with this trend. First, new generic drug products are constantly approved in the range of 600–1,000 items per year after both the re-examination period and originator patent expiration, and almost all generic drug applications use the MF system in general [21]. Second, DMFs are registered for the purpose of being quoted as a secondary source for approved generic drugs. The increase between the FYs 2013 and 2015 might have been influenced by the securing of a second source based on the Roadmap published in 2013. As indicated in Figure 5, 10 or more DMFs may be registered for one API. The number of DMFs registered will increase with the development of new generic drugs, particularly when the originator is a blockbuster drug. All registered DMFs are important for the stable supply of APIs and for promoting the use of generic drugs in the Japanese market.

DMFs are to be filed with a lot of information on APIs, and appropriate management of these important documents over their life cycles is necessary. Our results revealed that Japanese DMF registrations are already globalized along with the globalization of the API supply chain. Similar DMF systems have been individually developed by many regulatory organizations throughout the world [12, 13]. There are differences among their DMF systems and regulations, such as assessment processes for DMFs and technical requirements for APIs [12]. On the other hand, quality deficiencies such as insufficient control of impurities found in DMFs or API related documents have attracted considerable attention [22–26]. In such situations, appropriate management of DMFs in accordance with each regulation may be a complication for global API manufacturers; however, it is essential for the stable supply of APIs and the generic drugs using them. Therefore, at present, it is imperative that the Japanese DMF system and DMF related regulations are understood by all DMF registrants, including foreign registrants. To attain this goal, relevant documents have been posted on the PMDA website [27]. However, the ultimate goal in the future would be the global convergence of DMF systems and their regulations. To realize this vision, some challenges should be taken step by step. For example, implementation of guidelines of the International Council for Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for Human Use (ICH) is important. ICH guidelines are basically applied to new drugs in Japan; however, not all guidelines are currently applied to generic drugs. This would be because the MHLW must carefully consider the timing and manner of applying ICH guidelines to generic drugs. Some ICH quality guidelines, such as ICH Q3A guideline entitled ‘Impurities in New Drug Substances’, have already been applied to generic drug assessment [28]. Recently, implementation of ICH Q3D guideline for elemental impurities has been a topic of debate in the field of generic drug assessment and pharmacopoeia in Japan [29, 30]. Although the ICH Q3D guideline is not yet implemented for generic drugs in Japan, we hope that such impurities would be globally controlled based on the latest scientific knowledge to keep up with the diversity of the supply chain for generic drugs. With regard to implementation of the ICH Q3D guideline, harmonization of test methods for elemental impurities is expected, and this is discussed by the Pharmacopoeial Discussion Group (PDG) among the Ph. Eur., USP and JP [31]. Moreover, other test methods, such as chromatography, are expected to be harmonized by the PDG and be made available to manufacturers across the world. Additionally, like for the pilot project of montelukast sodium monograph, harmonization of API monographs in pharmacopoeia as much as possible would be useful [19]. Before the API supply chain was globalized, Japanese regulations pertaining to generic drugs might have been developed for Japanese manufacturers only; however, with the globalization of the API supply chain, regulations need to be updated. We focused on the DMF system, which is one of the most relevant regulations for the API, and clarified the detailed DMF registration situation in Japan. Further development of considering globalization, such as harmonization and regulatory convergences, would facilitate optimum quality assurance and the stable supply of APIs and generic drugs of using them. Furthermore, it would also promote global health by enabling efficient utilization of limited resources.

Conclusion

This is the first manuscript presenting the current situation of the Japanese DMF registration in detail. Since the start of the MF system in 2005, 3,804 DMFs have been registered. This study shows that 36.54% DMFs were registered by Japanese manufacturers, whereas 63.46% DMFs were registered by foreign manufacturers. DMFs were registered from 46 countries and regions worldwide, mainly from Asia and Europe. The highest numbers of registrations were from Japan, followed by China, India, South Korea, Italy, and Spain. These results demonstrate that DMF registration has already globalized in Japan. In recent years, approximately 200–300 DMFs have been registered every year. The ratio of foreign registrants to total registrants for one API was different for each API. Sometimes, more than 10 DMFs may be registered for one API. We speculate that the total number of DMFs registered will increase in proportion to the development of new generic drugs in the future. These DMFs are essential for the stable supply of APIs and for promoting the use of generic drugs with reliability of the stable supply. To secure the stable supply of APIs, appropriate management of DMFs is necessary, implying that the Japanese DMF system and its related regulations are understood by all DMF registrants including various foreign registrants. Furthermore, it is essential that the DMF system and its associated regulations are globally convergent to promote easy registration and management of DMFs. We hope that the present study will help understand the situation of the Japanese DMF registration.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Enago (http://www.enago.jp) for the English language review.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this manuscript are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official views of the Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency.

Competing interests: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Authors

Maki Matsuhama, MSc

Office of Standards and Guidelines Development

Ryosuke Kuribayashi, PhD

Office of Generic Drugs

Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency, 3-3-2 Kasumigaseki, Chiyoda-ku, Tokyo 100-0013, Japan

References

1. Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Estimates of national medical care expenditure, FY 2014 [homepage on the Internet]; [cited 2018 Jan 23]. Available from: http://www.mhlw.go.jp/toukei/saikin/hw/k-iryohi/14/dl/kekka.pdf (Japanese)

2. Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Estimates of national medical care expenditure, FY 2014 [homepage on the Internet]; [cited 2018 Jan 23]. Available from: http://www.mhlw.go.jp/english/database/db-hss/dl/digest2014.pdf

3. Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Health Insurance Bureau, 2013 [homepage on the Internet]; [cited 2018 Jan 23]. Available from: http://www.mhlw.go.jp/english/policy/health-medical/health-insurance/dl/health_insurance_bureau.pdf

4. Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Promotion of the use of generic drugs [homepage on the Internet]; [cited 2018 Jan 23]. Available from: http://www.mhlw.go.jp/english/policy_report/2012/09/120921.html

5. Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Action program for the promotion of the safe use of generic drugs. 2007 Oct 15 [homepage on the Internet]; [cited 2018 Jan 23]. Available from: http://www.mhlw.go.jp/houdou/2007/10/dl/h1015–1a_0001.pdf (Japanese)

6. Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Road map for further promotion of use of generic drugs. 2013 Apr 5 [homepage on the Internet]; [cited 2018 Jan 23]. Available from: http://www.mhlw.go.jp/bunya/iryou/kouhatu-iyaku/dl/roadmap02.pdf (Japanese)

7. Japanese Cabinet. Basic policy on economic and fiscal management and reform 2015. 2015 Jun 30 [homepage on the Internet]; [cited 2018 Jan 23]. Available from: http://www5.cao.go.jp/keizai-shimon/kaigi/cabinet/2015/2015_basicpolicies_en.pdf

8. Mitsubishi UFJ Research & Consulting Co., Ltd. Business report on verification and investigation of road map in FY 2014 [homepage on the Internet]; [cited 2018 Jan 23]. Available from: http://www.mhlw.go.jp/file/06-Seisakujouhou-10800000-Iseikyoku/0000095057.pdf (Japanese)

9. Zimmermann J, Sutter B, Bürger HM. Crystal modification of a n-phenyl-2-pyrimidineamine derivative, processes for its manufacture and its use. WO 1999003854 A1.

10. Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Guideline on utilization of master file for drug substances. 2005 Feb10 [homepage on the Internet]; [cited 2018 Jan 23]. Available from: https://www.pmda.go.jp/files/000153843.pdf

11. Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency. Master file system for drug substances. [homepage on the Internet]; [cited 2018 Jan 23]. Available from: https://www.pmda.go.jp/files/000153373.pdf

12. Matsuhama M, Takishita T, Kuribayashi R, Takagi K, Wakao R, Mikami K. Similarities and differences of international practices and procedures for the regulation for active substance master files/drug master files of human use: moving toward regulatory convergence. J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2016;19(2):290-300.

13. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. Drug master files: guidelines. 1989 Sep [homepage on the Internet]; [cited 2018 Jan 23]. Available from: http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/GuidanceCompliance RegulatoryInformation/Guidances/ucm122886.htm

14. Bennett S. China’s growing presence in the global supply chain. Chimica Oggi/Chemistry Today. 2012;30(1):56-8.

15. Department of Health and Human Services. Food and Drug Administration. Statement of Deborah M Autor, esq. Securing the pharmaceutical supply chain. 2011 [homepage on the Internet]. [cited 2017 Jan 23]. Available from: https://www.help.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/Autor1.pdf

16. European Commission. Implementation of the new rules on importation of active substances. 2013 [homepage on the Internet]; [cited 2018 Jan 23]. Available from: http://ec.europa.eu/health//sites/health/files/files/committee/70meeting/pharm622.pdf

17. Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan. Countries & Regions [homepage on the Internet]; [cited 2017 May 11]. Available from: http://www.mofa.go.jp/region/index.html

18. Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Japanese Pharmacopoeia 17th Edition. 2016 [homepage on the Internet]; [cited 2018 Jan 23]. Available from: http://www.pmda.go.jp/english/rs-sb-std/standards-development/jp/0019.html

19. Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency. Pharmacopoeial Harmonization. Pilot Project [homepage on the Internet]; [cited 2018 Jan 23]. Available from: http://www.pmda.go.jp/english/rs-sb-std/standards-development/jp/0007.html

20. Mizuho Information & Research Institute, Inc. Business report on verification and investigation of road map in FY 2015 [homepage on the Internet]; [cited 2018 Jan 23]. Available from: http://www.mhlw.go.jp/file/06-Seisakujouhou-10800000-Iseikyoku/0000129611.pdf (Japanese)

21. Kuribayashi R, Matsuhama M, Mikami K. Regulation of generic drugs in Japan: the current situation and future prospects. AAPS J. 2015;17(5):1312-6.

22. Borg JJ, Robert JL, Wade G, Aislaitner G, Piroźynski M, Abadie E, Salmonson T, Vella Bonanno P. Where is industry getting it wrong? A review of quality concerns raised at Day 120 by the Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use during European Centralised Marketing Authorisation Submissions for chemical entity medicinal products. J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2009;12(2):181-98.

23. European Directorate for the Quality of Medicines & HealthCare. Top ten deficiencies: new applications for certificates of suitability (2011). 2012 [homepage on the Internet]; [cited 2018 Jan 23]. Available from: https://www.edqm.eu/medias/fichiers/paphcep_12_15.pdf

24. Diego IO, Fake A, Stahl M, Rägo L. Review of quality deficiencies found in active pharmaceutical ingredient master files submitted to the WHO prequalification of medicines programme. J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2014;17(2):169-86.

25. Zhang H, Li H, Song W, Shen D, Skanchy D, Shen K, Lionberger RA, Rosencrance SM, Yu LX. Completeness assessment of type II active pharmaceutical ingredient drug master files under generic drug user fee amendment: review metrics and common incomplete items. AAPS J. 2014;16(5):1132-41.

26. Sun IC. Advantages of using an abbreviated dossier for drug master file applications in Taiwan. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol. 2016;80:310-3.

27. Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency. Master file system [homepage on the Internet]; [cited 2018 Jan 23]. Available from: https://www.pmda.go.jp/english/review-services/reviews/mf/0001.html

28. Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Answers to questions about generic drugs. 2015 [homepage on the Internet]; [cited 2018 Jan 23]. Available from: http://www.mhlw.go.jp/file/06-Seisakujouhou-10800000-Iseikyoku/0000078998_3.pdf (Japanese)

29. International Council for Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for Human Use. Guideline for elemental impurities, Q3D [homepage on the Internet]; [cited 2018 Jan 23]. Available from: http://www.ich.org/fileadmin/Public_Web_Site/ICH_Products/Guidelines/Quality/Q3D/Q3D_Step_4.pdf

30. Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Basic principle for preparation of JP18th. 2016 [homepage on the Internet]; [cited 2018 Jan 23]. Available from: http://www.pmda.go.jp/files/000214665.pdf (Japanese)

31. Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency. Press Release for Pharmacopoeial Discussion Group achievements, 2016 [homepage on the Internet]; [cited 2018 Jan 23]. Available from: https://www.pmda.go.jp/files/000214807.pdf

|

Author for correspondence: Maki Matsuhama, MSc, Office of Standards and Guidelines Development, Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency, 3-3-2 Kasumigaseki, Chiyoda-ku, Tokyo 100-0013, Japan |

Disclosure of Conflict of Interest Statement is available upon request.

Copyright © 2018 Pro Pharma Communications International

Permission granted to reproduce for personal and non-commercial use only. All other reproduction, copy or reprinting of all or part of any ‘Content’ found on this website is strictly prohibited without the prior consent of the publisher. Contact the publisher to obtain permission before redistributing.